Eight or nine years ago – I think it was summer 2012 – I found myself browsing the shelves at a bookstore in Tehran.

Outposts of the local bookstore chain Shahr-e Ketab glitter like branches of Barnes & Noble, selling books alongside silly gadgets and book-related tat. You can buy a mini Persian-carpet mousepad, or a leather pencil case stamped with arabesques, or a set of Mondrian coasters (I’ve been tempted by all but only have the first, a gift from my sister). If you are there for the books, you can peruse a sizeable number of works in translation and find most books you’re looking for in the original Farsi, whether modern classics or contemporary, poetry or fiction, assuming of course they aren’t at that moment banned. (In Iran censorship is dynamic: books appear and disappear from the shelves depending on the season; just because something was once banned doesn’t mean it will be forever, and just because something wasn’t doesn’t mean it won’t ever be.) Unlike the pricey objets that constitute print literature back in the US – known here under the umbrella term ‘abroad’, kharij – these books are, by and large, printed in sensible fonts on cheap, fluorescent draft paper – more Reddi-wip than crème brûlée. In a literate society, the theory seems to go, people should be able to afford new books in print, even in the Internet Age.

On this particular afternoon my cousin was playing the role of literary stylist, guiding me, through the terrain of contemporary Iranian fiction with undo patience. Besides religiously attending a Farsi poetry circle with my parents in the Cleveland suburbs throughout my adolescence, I’d minored in Persian literature in college, and yet my knowledge of the canon was limited to the classics, i.e., to poetry by the likes of Ferdowsi, Rumi, and Nizami from the tenth through to the fourteenth centuries. It was time, I decided a couple years out of college, to familiarize myself with the modern canon.

‘Oh and this one,’ my cousin said, placing another book on my growing stack. ‘This got a lot of buzz. Edgy, feministy, written by a woman – you’ll like it.’

The book was Negaran nabash by Mahsa Mohebali, packaged in a thin, gray volume. The book’s title – ‘Don’t Worry’, translated literally – appears in barberry red (zereshki) across the front, in a hue as muted as the title’s warning. Underneath, a surrealist sketch shows a woman sitting on a row of adobe huts, holding a bunch of balloons, or floating pills, and smoking a cigarette. One of the huts doubles as either the hem of her skirt or her legs, depending on how much femininity one ascribes to the sparsely outlined figure. In short she’s the stuff her city is made of, and vice versa.

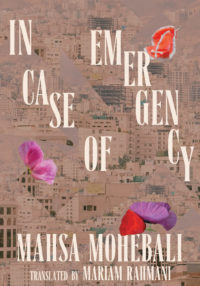

Our ownership of public space as citizens, drugs and addiction, the transgressions invited by binary gender – these are all themes of In Case of Emergency (the title of the English edition). Inside this quiet cover, the story is screaming.

The novel follows Shadi, a rich, disillusioned junkie, as she roams through a crumbling Tehran, searching for her next fix. The city is being hit by a series of back-to-back earthquakes that are sending the yuppies fleeing, with her own family first among them. Shadi opts out of this exodus, instead navigating a bubbling underworld of punks and pretty boys as she goes to visit friends who are as sad and messed up as she is. The pages of In Case of Emergency are rife with street fights and opium pipes, suicide attempts and betrayals. (When it comes to the relationship between aggression and drugs – or for that matter, depression and drugs – the story suggests, it’s chicken or egg.) The titular advice, it turns out, is bitingly sarcastic. Don’t worry? Everyone’s worried – the world is falling apart. Or to put it more like Shadi and her friends might: it’s the apocalypse, and people are freaking the fuck out.

Consider packaging a book like this as a well-respected publisher in a country in which husbands and wives still refer to each other by the titles ‘Ms’ and ‘Mr’ in good company. When the Ministry of Culture grants you the requisite license to publish – who knows why, least of all you – you think there’s no need for hubris. A gray cover will do. As if to say: So it’s the apocalypse, let’s share a smoke.

*

That afternoon in Tehran I knew nothing of the story inside the gray cover of Negaran nabash, nor of the story we’d share, the book and I. Little did I know at the time, but this was the text that would turn me into the translator I never wanted to be.

That afternoon at the bookstore, I trekked downstairs, twenty or so books tucked between chin and hands, to the register. I paid: some reasonable sum in toman, next to nothing in US dollars. Rather than go to the exchange, I’d traded my dollars with an aunt a few days prior in return for a thick wad of Iranian bills. Negaran nabash cost me 3,500 toman, or about $1.40 at the time. (Today, due to inflation in Iran, $1.40 would get you about 38,000 toman; my aunt’s investment in dollars paid off.)

Outside I parted ways with my cousin and walked the fifteen or so minutes back home, sweating in the summer sun. At home I put the stack of books on the wooden dresser in my grandmother’s old room where I was staying, sleeping on her old twin-sized bed – hers for as long as I can remember, even that first summer I visited Iran as a child, when my grandfather was still alive. He used to lay a dushak on the floor of the living room each night, folding and storing it in the closet come morning like a Japanese futon. Negaran nabash sat on top of the stack; I didn’t crack the cover.

It was a short trip, for a trip to Iran. As a kid, I’d spent long summers there whenever my parents could afford overseas tickets for six; as an adult I’d learned to travel counting days instead of months, like an American. A week later I packed Mohebali’s text and the rest of my bookstore hauls in a suitcase and went back to Dubai, where I was then living.

*

A year after that, I packed my life into two suitcases and moved back to the US, crashing on friends’ couches until I gained a footing in New York – and thus inevitably overstaying my welcome. From door to door, my books came with me. Read and unread.

Two years and some change after that, I moved cross-country to Los Angeles to start a PhD in Comparative Literature at UCLA. My partner and I in the car, the books in boxes on the Amtrak Freight.

In my second year of the program, I finally read Negaran nabash. I had to: the book was homework, assigned reading for a yearlong independent study in modern Persian literature. I fell for it. For Shadi. For how she swings from sarcasm to lyricism; for her wit, her acerbic critique. Shadi refuses to conform. Either to gender norms or to the rules of respectability. She is unapologetically rude, drugged and depressed. But she’s not the sick one. It’s society that needs to be cured.

Immediately after finishing the book, I searched online to see whether it had been translated into English and was surprised to learn that it hadn’t. What if I tried? I suppressed the idea; making time to work on my novel alongside graduate work was hard enough.

I’d never translated anything. I hadn’t wanted to. Translation had always struck me as unsexy. Or perhaps something more insidious than that. I was a bilingual-by-birth ‘comparativist’, as scholars in my field called themselves, and from professors to peers, people had always assumed I was interested in translating. But I refused. Probably for the same reason I foreswore pink when I left first grade: a sneaking suspicion that whatever skins people want you to wear must be exactly the wrong fit.

*

Reading Don’t Worry during the winter of 2017, as Trump’s ‘Muslim Ban’ came into effect, I couldn’t stop thinking about what an English translation of this work could do, literarily and politically. Negaran nabash flew in the face of the Orientalist stereotypes about Iran that I’d confronted growing up in the US, where Iran figures as a black hole of women hidden behind chadors. Photographs of Tehran ‘at play’ are typically from the 1960s and 70s, during the Shah’s reign, as if people stopped partying after the Revolution. In fact the party didn’t die after disco; it just went off-grid – as Negaran nabash depicts. I found myself talking about the need for this book to be translated for a US audience – until finally, a stranger at a barbecue told me to shut up and do it myself. Okay, fine.

I started with a test chapter. Did I really want to do this or was it just a fantasy? Rather than starting at the beginning, I jumped to my favorite chapter, chapter seven, in which the main character Shadi visits her childhood best friend, Sara, and they get high together.

Sara lives in a former palace that she inherited from her great-grandmother, who’s described as the nineteenth-century Nasiruddin Shah’s ‘soguli’ or harem ‘favorite’. The setting alone is a joke. And one that only gets better in translation: two girl friends flirting like girlfriends in a defunct harem. They tease a classic Orientalist fantasy and the male gaze – but only while defying every expectation of the sort of femininity that can be tied up in a bow. Shadi and Sara are rude, turning curse words like ‘kisafat’ (often ‘bitch’ in my translation) into twisted pet names, while Shadi, dressed in a field jacket, and wearing her hair short and spikey, sans hijab, presents as male in public, cross-dressing as a man in order to evade hijab law.

Which is all to say, this particular Orientalist fantasy comes with the finger.

*

We’re told that the immigrant experience is an act of translation: we translate ourselves back and forth in incessant loops. But to me the metaphor falls short. Growing up bilingual I rarely thought of myself as translating from one language to another. Instead each language had its own spaces.

English for the garage, for differentiating between Phillips and flat-head screwdrivers when my father, bent over a leaky faucet, told me what to run and retrieve from the toolbox. Farsi for the kitchen, for setting the table as my mother, bent over the stove, told me not to forget a kafkir for serving the rice.

English for explaining to friends at school that wearing hijab was freeing. Farsi for arguing fiqh with my parents at home, pushing the limits of Shia jurisprudence alongside my sister to wear sandals without socks, or let an anklet glimmer.

English for words like ‘chronic depression’. Farsi for naming exile, ghurbat, that experience of both being strange and finding everyone else so: strangeness and estrangement.

Both for laughter or love. Both for death, life’s purest translatable.

*

The challenges of translating the vernacular have been . . . trying, to put it politely. As the French translator Antoine Berman points out, the danger is falling flat. Dialogue is thorniest. How do you recreate Shadi’s and Sara’s cool in another language? How do you translate a spark?

Unfortunately, a vernacular clings tightly to its soil and completely resists any direct translating into another vernacular. Translation can occur only between ‘cultivated’ languages. An exoticization that turns the foreign from abroad into the foreign at home winds up merely ridiculing the original.

So writes Berman in an oft-taught 1985 essay, ‘Translation and the Trial of the Foreign’, as translated into English by Lawrence Venuti. I couldn’t disagree more.

Still, time and time again I’ve been afraid that I have, as Berman cautions, ‘winded up merely ridiculing the original’. In final editing this past summer, four years after trying my hand at that first chapter, I still left my work sessions frustrated and deflated. Pages covered in red. Unsolved phrases stuck in my head. Waking me up at night, when I’d reach for my phone and jot down the nth-number solution to test in the clarity of day.

To put it less politely, translation is a bitch.

*

The first time I met the book’s author, Mahsa Mohebali, in person was for lunch at a steak house of her choosing. I’d gotten permission from her to start working on the translation the previous year, sending her chapter seven as a sample.

It was summer, too hot to walk; I took a Snap (Iran’s Uber). The place didn’t show up on Google Maps but Mahsa had given me a street address. On the ride over I was inexplicably nervous. In general I’m not a timid person, and certainly not professionally. But this meeting was in Farsi. Sure, I wrote to Mahsa in Farsi, changing my keyboard to Arabic script when I wasn’t being lazy and typing in Pinglish (Farsi in Latin script) when I was; and sure, we’d Skyped in Farsi a couple times – but that was different. That was nuts and bolts. This was social. What if I sounded stupid? Would she still trust me to translate Shadi’s somehow simultaneously crass and chic style?

The steak house was small, with high ceilings and a waiter wearing a crisp button-up and trousers, maybe even a cummerbund, if memory serves. We were the only two customers.

We chose our steaks, the sauce and the cooking; I ordered water, Mahsa a virgin mojito. We started talking. Everything from identity politics to the pitfalls of post-feminism. Less eloquently so on my part, but I kept up.

Two hours later when the bill came, Mahsa insisted on paying. I couldn’t keep up with her hospitality, and it embarrassed me. Even more so because I was paid in dollars – by then the value of the toman had dropped again, making my graduate stipend go even further than my previous trip. But also because, given the difficulty of getting a US visa on an Iranian passport, it’s unlikely I’ll ever be able to host her in the States to return the favor.

*

If translating a vernacular is an impossible task, then that’s exactly why it must be done.

As an English translator working in the West – as opposed to say, in a postcolonial Anglophone context such as Nigeria or India – I feel this urgently. Writing a couple of decades after Berman’s 1985 essay, David Bellos points out how often translation takes for granted a level of familiarity between the cultures of the source and receiving languages. Weighing in on the foreignization versus domestication debates – the theory goes that a translator must choose between bringing the reader to the original text, or bringing the original text to the reader – Bellos rightly claims that ‘foreign-soundingness’ is ‘only a real option for a translator when working from a language with which the receiving language and its culture have an established relationship’.

How is that possible between countries that have cut off direct relations since 1979, in the wake of the Iran hostage crisis and Islamic Revolution?

In translating In Case of Emergency, I’ve tried to believably make Iranian characters speak a cosmopolitan American English with an international flair. More than just bearing out Bellos’ logic about translating across a cultural gap, this has been my own small attempt to bridge that gap. Here are characters who might not look like you, but they do sound like you – or as close as they can without erasing their own individualities and cultures.

*

Translation is an act of service. Not to the author, nor to the national literature that’s being translated, but rather to the language into which one’s translating. Bent to match the musicality of Farsi or weighted with the strangeness of a fresh idiom, our English is enriched.

Like the politics of translation, the economics of translation are largely effaced. In ‘Some Notes on Translation and on Madame Bovary’, Lydia Davis refreshingly disabuses us of this fantasy. ‘If a translator is poorly paid,’ Davis writes under a section wryly titled ‘Independent wealth’, ‘she must work quickly in order to earn anything like a living. If she is well paid, she can work more slowly. The independently wealthy can work as slowly as they like on a translation.’ Davis then writes of calculating her rate for translating a novel by Maurice Blanchot after the fact, only to discover she’d made a dollar per hour.

If for different reasons than the independently wealthy, graduate students in the humanities are also accustomed to taking on long, laborious projects that are un- or underpaid. When I committed to translating Negaran nabash, I consciously decided not to keep track of my hours. I knew full well that beyond actually translating the text, my work would include not only selling myself, but also selling the book. The former hurdle was, for a first-time translator, fair. Less fair was the resistance to contemporary Iranian literature in translation that pervades in the US. In the Orientalist imaginary, Iran is stuck in the past; the contemporary publishing industry is often guilty of producing this same fantasy.

The price of translation is tied to the field’s feminization. Compared to the historically masculinized project of authorship, translation has long been seen as woman’s work. No wonder it’s undervalued.

Over four years and one PhD after taking this project on, I am finally counting down to a publication date. In a spring car ride across Los Angeles, the roads quieted by Covid-19, I did an approximate calculation of my expected rate by the time the book comes out, taking into account both my publisher’s advance and a PEN/Heim grant, figured against an average ten hours per week. I’ve fared much better than Davis, at about three dollars per hour. Less than a latte. That’s the cost of translation, and it’s the translator who pays.

*

The second time I saw Mahsa Mohebali was at a café that’s a favorite haunt of Tehran’s literary circles, where we’d arranged to sign an author-translator agreement a week after that first luncheon. We sat on a wide second-floor terrace green with potted plants that looked even more spectacular against the city’s gray smog.

But before contracts, we ordered coffee and cigarettes. And something sweet.

Sitting there I reflect on the strange relationship between an author’s work and a translator’s. Imagine you are giving a writing exercise. You are told what to write about, and in what order. You are told what metaphors to use, what images to describe. You are dictated the style. In a way, you’re writing a pastiche, but with one caveat: you must not reproduce any of the author’s language. None of the same characteristic turns of phrase, none of that particular way of defying grammar that’s so weird but good. You “must” not parrot the author because you cannot – because in fact you are writing in a different language altogether. This is the task of the translator. To tell another’s story. Painstakingly, with a patience you hardly afford your own.

My tart arrives only with the second coffee. I see why Mahsa brought me here. It’s the sort of place where no one’s in a rush, least of all the waiter. Slices of nectarine, expertly thin, glazed golden, in a spiral. Like flower petals. Or no – more like a different sort of flower, feminine, embodied. Speaking Farsi, we get at the reference via evasion rather than euphemism: the term ‘flower’ doesn’t have the same double entendre as in English. We both laugh. I mention Georgia O’Keeffe. Mahsa doesn’t know her. So I think to myself: How weird, and wonderful, that so much translates precisely when nothing does.

You have this tongue that turns in multitudes. Use it. Let it tangle and twist. Let it knot. You will always find a way out.

Photograph © Paula Gimena

In Case of Emergency comes out on 30 November from Feminist Press.