The men sprawled in the office in leather armchairs, drinking coffee and Torres 10 brandy. They smoked cigars while discussing the energy crisis and the Middle East’s bid to enter the world of capital. How are we supposed to manage without oil? They’d better not tell me to tighten my belt. Don’t worry, Mateu reassured them, we have plenty of reserves. There’s oil from Venezuela, Lluís said. Sure, Mateu replied, except it’s nationalised. Don’t you think Russia is behind all this? I bet they made a deal with the Arabs just to mess around the Americans, Ramon said. It’s certainly possible . . . Merche unwrapped the Tupperware and set it all out on the glass table in the sitting room. The women were drinking black tea with lemon, with the exception of Dolors, who wanted hers with skimmed milk. Tea or coffee? Sílvia had asked the men. Coffee, Lluís said. And a drink too! the others protested. Why not a cigar, while we’re at it? Lluís suggested, taking a box of Montecristos from the walnut desk drawer. As Sílvia served her girlfriends tea, she whispered, As soon as they leave, I’ll bring out the pastissets. They all laughed, delighted to be her accomplice. What’s so funny? Ramon asked from the office, whose door had been left open. Nothing, just girl stuff . . . Merche had removed the last of the plastic containers from her leather suitcase, which had purple marbling. What a pretty suitcase, Sílvia said. I bought it in Italy, Merche replied. And it isn’t a knock-off, you know! Real leather. I saw one just like it at Loewe, Teresa added. Sure, those aren’t authentic, though; I saw them in the shop window as well.

Now look, Merche said, Tupperware containers come in a bunch of sizes . . . But Rexach is constantly offside, Mateu complained. He’s a lump, Ramon noted. No, he isn’t. The issue is he’s chicken. The guy’s got a good pair of legs on him too, Lluís added. Me, I’m partial to El Cholo. You mean Sotil? That’s right. You know, I heard he used to live in one of those flats in Pedralbes that’s worth millions and that he and his family ate on the floor. I don’t get it, Ramon said. When he could’ve been living like a king . . . Merche held up a container. This big one here is good for vegetables or salad. Or a kilo of meat! Dolors teased. They don’t look so different from the ones at the grocery store. True, but food stays a lot fresher in these than it does in any container you’ll find at the market. A week, fifteen days, you name it. All you have to do is put the seal on tight and push down on this little flap sticking out from the lid, then lift the seal a teensy bit on one side and let the air out. See? Like this, right on the middle of the lid. With no air inside, the food stays fresher. But meat spoils after two weeks, Dolors insisted. Honey, you are dumb as a box of rocks. Didn’t you hear what I just said? Teresa was seated on a leather barstool, arms crossed at her chest and legs tucked beneath her. Dolors was lying on a rug on the floor, smoking one cigarette after another. Sílvia had remembered to put the biggest ashtray next to her. Dolors was wearing a leather, antelope-skin miniskirt and matching greyish boots. She had a very thin black line pencilled over her eyes and light-green eye shadow. Merche was the dressiest of the four friends and wore fake eyelashes, which she fluttered with a mix of innocence and guile. She was awfully proud of her husband. The man’s a genius, she asserted, and he did it all on his own. The four women had succeeded in getting their respective husbands to become friends with each other, which is how they themselves had managed to stay friends since convent school. Lluís designed the Mateus’s and Renaus’s houses in Pineda, and Tomàs helped them get an overdraft at the bank.

Albert Mateu wore a beige sweater, and corduroy trousers that were a shade darker, and Lluís a chequered pullover like the ones popular in the 1950s. The women would go out shopping together for their husbands and, while they were at it, catch up over tea. Teresa, who sat closest to the men, eavesdropped on their conversation and giggled at Ramon’s wisecracks. Merche continued, There are smaller ones too, perfect for storing grated cheese. Dolors whispered to Sílvia, It’s always best to keep the men where you can see them, not out and about. The two women laughed and stared at Teresa, who was listening to Merche go on about how to prevent aioli from separating. Store the meat in the freezer and I swear it keeps longer than fifteen days, Merche said with her eyes on Dolors, who barked with laughter. You mean, they’re better when we can see them. Sílvia winked at Teresa and Dolors. The two of you are shameless! I’m quite happy with my husband away, said Teresa, who had heard everything. Sure you are, Sílvia replied. Will you please all listen to me, yelled Merche, who was beginning to feel put out. Oh, honey, we’re sorry, the three women said and turned their attention to the containers. These round ones are for broth. But all you girls do is complain, Teresa said, her cotton-white skin a touch loose and her hands clear as lampshades. What matters is that your man sticks with you, she said, misty-eyed. It’s not like you see much of your own husbands. The veins in Merche’s neck were beginning to pop. The three of you are going to drive me up a wall, she said. Tupperware is better than tin foil. More practical, cheaper in the long run. Plus, it can hold liquid and all the rest. See them? Please, said Sílvia. They’re never home. Meanwhile, we’re whisking the children all over the city, Teresa added. Sílvia turned to Dolors: You wouldn’t have a recipe for stuffed cabbage, would you? Why do you ask? My sister-in-law’s back, I want to make it for her one day. That minx is home, is she? Teresa asked. She’s not a minx, she’s just different, Sílvia said. Merche turned to Teresa. My ears haven’t stopped ringing from my kids shrieking in them. All I do all day long is wipe snot and clean up pee. Don’t you have a sitter? Teresa asked. Of course I do, but I’m their mother . . . If I were you, I’d put them in daycare. But Ramon won’t allow it. He says children need to be with their mothers. I agree, Teresa said. I for one would like to work, Sílvia told Dolors. Merche heard her and jumped in. You should do Tupperware demonstrations like me. They’re a hoot, there’s free food and you get to spend time with your girlfriends. Merche addressed everyone, Now, if you could all please let me know what you’re planning to buy, or I won’t get my commission and poor Sílvia won’t get her gift. Dolors picked out two of each – she figured she could give a set to her mother, who was becoming more sophisticated by the day – and Teresa four small ones. What a cheapskate, Merche said under her breath. Well, my husband won’t hear a word about me working. Neither will mine, Teresa added. He hasn’t exactly said no. He just passively resists. You know, Merche said, the last time I got pregnant was when I saw Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca on TV. Don’t you think my Ramon looks a bit like Humphrey Bogart? Especially when he half smiles with his left side. If you say so, Sílvia teased, and they all burst out laughing.

The men left to watch the match. Mateu lingered at the door, then turned to Teresa and said, You’re looking better every day. Obvious, isn’t it? That her husband’s not around, Dolors whispered to Sílvia. Sílvia slowly shut the door and then waited a minute until she heard the hum of the elevator. She called out, They’re gone! The others responded, Hurrah! Bring out the pastissets, Dolors commanded. Sílvia went to the kitchen, where she arranged the custard-filled pastries on an oval platter. Merche scowled, Aren’t you wicked, depriving the poor men of dessert. Don’t be a hypocrite, Teresa replied. Dolors asked, Should I grab the sherry? The cognac too, Sílvia suggested. We’re going to go crazy today, Merche exclaimed and then let out an electric shriek. Woo! Teresa joined in, clapping. The four women sat around the glass table, then dug in. I live for sweets, said Sílvia, her lips smeared in custard. The Tupperware had been set aside, the suitcase was open and papers were scattered all over the floor. Kneeling, they took one pastisset after another. I absolutely love custard, Dolors fawned with her mouth full. The bottles on the floor got emptier and emptier. Teresa was on her fourth glass of sherry. Greedy, greedy, she chided Sílvia. Says the pot to the kettle, you lush. This sherry is divine. Dolors went, Say xérès, like the French. It sounds more elegant that way. Teresa’s tongue was thick. If I say xérès, does that make this a fête? I guess it kind of does, Sílvia reflected. Lluís says we’re European. Is that right? Merche giggled. Long live Europe! Sílvia fluttered her arms like she was performing the dying swan. You’re all a bunch of snobs, Dolors snapped, her eyes flashing. Merche: Oh dear, I feel a bit woozy. You really can’t hold your drink, can you? Dolors teased. The bottle of sherry was half empty; Teresa, Merche and Dolors were sherry drinkers, while Sílvia preferred cognac. Look, look, watch me gargle, Sílvia cried out. Doesn’t that hurt your throat? Teresa asked. I like cognac. Sílvia licked her lips. But remember, according to TV, it’s a man’s drink, Dolors reminded her. The liquid was disappearing faster and faster from the bottle. Their cheeks were ablaze. I’m burning up! Sílvia yelled, yanking off her turtleneck sweater. Now there’s an idea, Dolors said as she undid her blouse and her skirt, stripping down to her tights and bra. Teresa was the last person to undress. What an adorable set, Dolors said, complimenting Sílvia’s black-lace bra and knickers. You like it? I’ve always enjoyed wearing nice underwear. I don’t, Teresa said. I mean I don’t care, considering what they’re for. Let’s play a game, Merche suggested. Let’s! Teresa clapped. How about charades? Oh, fun! Dolors and Sílvia exclaimed at the same time. Who’s up first? Dolors volunteered Sílvia. Why me? Because you’re the host . . . And who baked you those pastissets, hmm? You’ve no shame, Dolors. Now, now, girls, don’t fight, Teresa said. We’ll count it out. Eeny, meeny, miny, moe . . . Merche’s up. That’s not fair. Afraid so, love. The numbers don’t lie. Merche left the room. She was gone for a while. She sure is taking her sweet time. You’re not a cow! No need to chew it over so hard. As they waited for her to finish mulling, the three of them whispered, now and then roaring with laughter. Merche came back and the three formed a circle around her. She knelt on the floor, looked up and brought her hands together as if in prayer. An anchorite! Sílvia called out. Merche gestured to say no. A saint. Merche lowered her head. But what saint? Merche nodded. She lifted her shoulder and drew a large circle around her head. An important saint. Merche waved her hand. Got it, Dolors said. A very saintly saint who prays a lot. Teresa cut in, St Maria Goretti! But Merche shook her head. If it isn’t St Maria Goretti, then maybe it’s St Gemma Galgani. Merche shook her head again. Oh, oh, I know! Sílvia cried, clapping her hands. St Eulalia. Merche said yes, then, Phew! St Eulalia, Teresa grumbled. What are you complaining about? It was an easy one . . . Your turn, Sílvia, since you got it right. I already thought of one, so you don’t get to talk behind my back. So mistrustful! Sílvia bent over, as if she had a large humpback. The Hunchback of Notre Dame! Dolors yelled. Sílvia shook her head. It is a hunchback though, right? I suppose it could be a camel . . . Sílvia shook her head again. All right, a hunchback. But who is it? All three women were deep in thought. Rats, I can’t think of anyone. Who could it be? Teresa asked and Sílvia laughed. She pointed at her upper lip and drew prickly hairs with her fingers to show she had a moustache. A hunchback with whiskers? Sílvia planted herself in front of Teresa and slapped her on the cheek. Ouch, that hurt! Sílvia rolled her eyes back and moved her hands around restlessly. What are you doing now? I think she’s praying the rosary, Merche said. Teresa and Dolors both called out at the same time: Mother Rosario? Sílvia nodded. The sherry and cognac bottles were now empty. The women’s eyes gleamed, growing wider and wider. Now let’s do the time the nuns tried to burn Sílvia’s hands, Dolors proposed. Remember? Merche and Teresa said, Of course we do. Don’t touch me! Sílvia cried out, but the three women were already on top of her. Sílvia was on the verge of tears. Leave me alone, please, leave me alone! But Dolors wasn’t listening and her hands grabbed at Sílvia. Teresa mumbled, Maybe we should stop . . . Then Dolors said in Spanish: I am Mother Asunción and you are Mother Superior. She went to Sílvia’s bedroom and came back wearing a blanket over her head. Sílvia Claret, you look filthier every day. Please inform your mother that if she doesn’t wash your uniform tomorrow, we’ll have no choice but to burn your hands. And Sílvia went, No, please. I promise not to do it again. Fine, Dolors said. In that case, pray three Hail Marys. Merche was playing Sílvia’s mother, You can tell Mother Asunción I’ll wash your uniform when I feel like it. Sílvia turned to Dolors, My mama says she’ll wash my uniform when she feels like it. Dolors’ eyes glazed over. Hmm, I see. Her mouth widened into a large grimace. Is that right? Then I guess we shall have to burn your hands. Merche was in the kitchen, where she made a show of lighting the stove. Teresa and Dolors dragged Sílvia toward her. No, Mamà, please, don’t let them do it! Sílvia cried, but the two nuns howled even louder, and the Mother Superior slapped her on the mouth. Shut up, you insolent child. Sílvia was sweating and her hair was tousled. She cried, Mamà, Papà! Come back, don’t leave me here. Speak Christian, Mother Asunción ordered. You’re a naughty, naughty girl! Sílvia’s bra straps had snapped, exposing one of her breasts. You dirty little Jezebel! Merche was in the kitchen, shouting, Let the devil take her! Mother Asunción covered her eyes and roared, Holy Mary Mother of God. You’re naked. A mortal sin. You’re going straight to hell! Their racket filled the sitting room and as the women dragged Sílvia to the kitchen, the corduroy pouffe shifted this way and that. The Mother Superior broke a ceramic ashtray with her foot. Sílvia held on for dear life to the curtains separating the sitting room from the dining room, unravelling the hem. They finally stepped into the kitchen. Merche, now Mother Sagrario, waited for them with the burners on. Just as they were going to place Sílvia’s hands on the fire, Dolors morphed into Mother Socorro, who said, What are you doing to my sweet child? Leave the poor girl alone. It isn’t her fault she has a bad mother. What about her grandmother? Mother Superior asked. Letting them walk around without sleeves on. Mother Socorro ran her fingers through Sílvia’s hair. But our girl is a perfect angel, isn’t she? She cradled her like a newborn babe. There, there, my angel, my little angel, said Mother Socorro while comforting Sílvia, kissing her on the lips, removing her bra and caressing her breasts. What about us? Mother Sagrario asked. What if the devil dresses up as a man? What will we do then? Merche transformed into a devil with horns, a tail and a bloodcurdling face. She pulled Teresa out for a dance while spitting left and right. They danced and the devil dressed as a man stroked her naked back, Mother Socorro said as the devil unbuttoned the girl’s blouse and his claws marked her for the rest of time, Amen. My sweet lamb, you must rule over men without them realising. Merche kissed Teresa’s breasts. Get away from me, you devil! I want to stay pure. Please don’t make me sin. Teresa folded her hands in front of her chest. But the horned devil had already mounted her – and he was howling, clawing, kissing and nibbling her body from head to toe. In a corner, Dolors was petting Sílvia. Merche jolted up and said, Girls, girls! What’s going on? You’re sinning! Then she pulled Sílvia and Dolors off one another and the two yelped in surprise. Let us now pray for forgiveness: O Lord, Jesus Christ, Redeemer and Saviour. The four women knelt beside the glass table, naked and dishevelled, surrounded by leftover pastries and empty bottles. For every sin we have committed, we shall stick a single needle in the Sacred Heart. Sílvia stood up and went to the sewing table, where she fetched a blood-red pin cushion in the shape of a heart. They each stuck in a needle.

It took a long time for the women to break out of their alcoholic daze. All four were draped over the corduroy pouffe. The first to wake up was Merche, who staggered to the bathroom to get dressed. She was in there for a quarter hour, in silence. Then the whoosh of water out of the toilet tank and the open tap sounded faintly in the sitting room. She left without saying goodbye. In the meantime, Teresa and Dolors helped one another to their feet. They shut themselves in the bathroom after Merche and pulled on their clothes, each assisting the other with her bra. They washed their faces and returned to the sitting room. They gave a feeble goodbye to Sílvia, then groped along the wall to the entryway. Alone in the flat, Sílvia remembered she needed to change for dinner at the Tennis Club. She turned on the shower in the bathroom and let the water trickle over her body, so hot the rising steam nearly burned her. She scrubbed herself with a sponge, but it was too soft, so she reached for the pumice stone. She soaped her body, then used the pumice stone on her skin – so hard, it turned bright red. There, I’m nice and clean now, she muttered to herself.

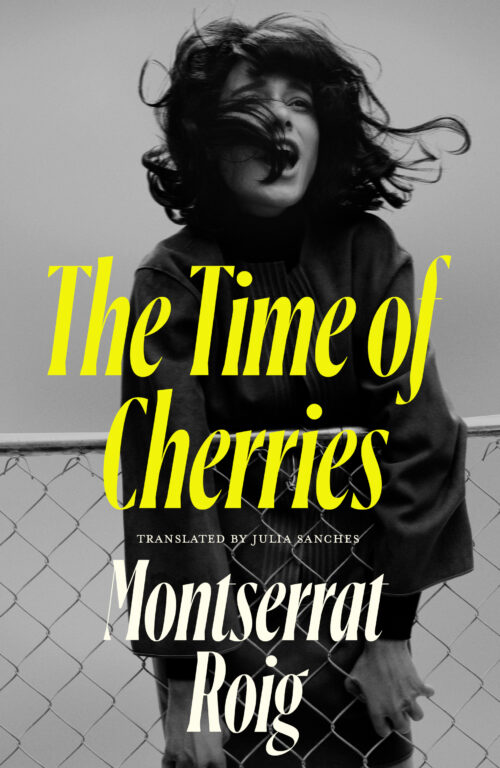

Image © Noah Ratcliff