I studied my reflection in the mirror. I recognised the image of a young but fallen woman. I leaned forwards and pressed my mouth to it. Fog spread across the glass like condensation in a room where someone has been sleeping deeply, like the dead. Behind me I saw the room reflected. On the bed lay hairpins, sleeping pills, and cotton panties. The sheets were stained with milk and blood. I thought: If someone took a picture of this bed, any decent person would think it was a reproduction of a young girl’s murder or an especially brutal kidnapping. I knew a woman’s life could at any point be turned into a crime scene. I had yet to understand that I was already living inside the crime scene, that the crime scene was not the bed but the body, that the crime had already taken place.

The bedroom window was open. The air smelled like water, bread, and citrus. I walked over and leaned out. Though the day had only just begun, the streets were steaming with late-summer rain, heat. At the intersection below, the traffic was already dense. Beyond the city, the mountains stood sharp against the sky, which was rumbling. At the horizon lay the large, glittering sea, cargo ships surging and sinking with the waves. The sounds carried far and freely, metallic and dulled. I heard a hammer strike concrete. I heard aeroplanes in the sky. Down on the square, a ball rolled across the flagstones. I saw a boy in a school uniform set fire to a piece of paper. I saw a girl dragging her dolly behind her. Above me hung the shining sun. I reached for the plane tree growing outside my window. I caught hold of a shoot and stuck it in my mouth. It tasted sweet and rough, like sunbaked resin.

I walked naked through the flat. The living room was all in beige and yellow. A thick dust rose from the wall-to-wall carpet. In the bathroom, the tap was dripping in the dark. I reached for the switch and the strip light crackled overhead. I twisted open the taps and filled the tub, poured in baby oil and bath salts I’d bought with my own money. I lowered myself into the water and leaned my head back. I reached for the hotel brochure, which I kept in the gap between the bathtub and the brown-tiled wall. Each spread showed a slice of life at the hotel. There were high-contrast photos in crisp jewel tones. Girls in pearl-white aprons, girls eating ruby-red apples straight from the tree, girls setting out coral-pink charcuterie during an excursion to a jade-green lake. I had already examined each spread many times. I knew there were tennis courts, a park, a ballroom. Mountains encircling a swimming pool, endless recreational options. I let the brochure sink through the bathwater and come to rest on my stomach, like a shroud. I reached for the shampoo, washed my hair until it squeaked. I scrubbed my cheeks and knees with a brush made of horsehair. I rubbed a small pale blue soap between my hands, and it lathered.

I climbed out of the bath and let the water drip from my body, wound my hair in a terrycloth towel, and walked through the flat, where the air was vibrating. I took out my traveling clothes. A pair of jeans and a shirt I’d stolen. Trainers made of cotton. I put on jewellery and ran my fingers through my hair, let it rest heavy against my back. I dabbed perfume on the dip of my neck and wrists. I applied lipstick. I sat down at my desk and wrote a farewell note to my parents. Finding the words was easy, because I had repeated them to myself all summer. I pressed my mouth to the paper.

On the windowsill in front of me, books were arranged in symmetrical piles, alongside incense and matches. Opposite, on the other side of the street, was an open window. I saw a child dressing another child. I saw a woman bending over a bed. I saw a man reaching out his hand and grabbing hold. Everything was as it usually was, for now. I reached for the ashtray and lit a cigarette, opened the window, and leaned out. The tar burned in my lungs and spread into my fingertips. If you can’t give your body the good stuff, give it the bad stuff. It started raining, the heat eased. I thought for a moment that my hands were giving off the scent of eucalyptus. I stubbed my cigarette out on the windowpane, let the rain wash over my hands for a while.

I folded up the note and walked through the living room for the third time. I always give a thought to when I do something for the third time. I’d advise all people to do the same. It’s important to be suspicious of that sort of repetition. I pinned the note to the noticeboard in the hall and turned in towards the flat, nodded to my parents’ wedding picture, which was hanging by the hall mirror, and picked up my suitcase, which was sitting by the door. I walked down the stairs and the stairs echoed. I took in the hallway’s smell of infants, cigarette smoke, boiled potatoes. I had with me a piece of bread and a pyramid-shaped carton of orange juice which I’d put in the freezer overnight. I had with me toiletries and hairbands and notebooks. I had with me a winter coat that I’d inherited. I had with me a silver-inlaid moonstone, which I took to be holy. Once on the street, I turned around and lifted my gaze. For a moment, I thought that my mother was waving from the kitchen window, like something out of a melodrama. What mother waves to her child from a window. I bit my tongue until it bled. Who are you when you leave your parental home? A young and lonely person en route to life.

The street was slick and smelled of rain, heat. I took it all in. Storing images as though in the face of death. I was a murder victim opening her eyes wide, as though to suck life in. There was the milk bar, where I had worked for many hours, letting my hands stack glasses and cups, wetting my lips with lukewarm milk from the cans. There was the swimming hall, where I had swum my lengths. The fountain and the department store. The fruit shop glowing in every colour. Ample piles of grapefruit and grapes. Water in plastic drums. The smell of dried figs and wet sand that washed over me as I neared the sea.

–

The station was deserted. People travelled later in the day or not at all. I held my ticket in my hand and the paper disintegrated against my skin. I got on the train. Outside the window, the mountains rose higher and higher and the greenery paled. I travelled through depopulated villages. I read, I wrote postcards, passing orchards, forests, watercourses. A young boy came by with a coffee cart. Chocolate and biscuits were on offer. I reached for a tin of mints but changed my mind. The carriage slowly emptied of people. With every station, someone disappeared. Women in black waved at children in black. A soldier was waving a pennant. People were embracing each other everywhere. In the end, I was there alone.

I rested my forehead against the window and opened my eyes wide. Suddenly everything out there seemed artificial. The mountains appeared to be lit up from below by a bright spotlight. At the foot of the mountain, the trees stood in perfect rows, as though dipped in wax and coated in glitter. On the rhododendrons hung dewdrops of silicone. A roaring waterfall, which seemed frozen in time. I looked at the mountains and the mountains looked back. Without a doubt an evil place in costume. Above the door, a neon sign started blinking – terminus in fluorescent green. I took the pocket mirror from my summer jacket’s inside pocket. My face was blank. My mouth was still bright red, but I touched up my lipstick anyway. I put the mirror away and gathered my things.

I stood up and got off the train. Here too the station was deserted. In the transit hall hung a clock. I noticed it was an hour off. The clock struck and a mechanical bird emerged from a hatch, as though guided by an invisible hand. Under the clock was a pool of water, which was expanding. The village was called Strega and it was in the mountains. Later I learned that Strega was a chamber of horrors, where everything had frozen into a beastly shape. I learned that Strega was deep forests bathed in red light. Strega was girls plaiting each other’s hair just so. Girls who carried large stones through the mountains. Girls who bent their necks and stood that way. Strega was a lake and the foliage enclosing it. Strega was a night-light illuminating what was ugliest in the world. Strega was a murdered woman and her belongings. Her suitcase, her hair, her little boxes of liquorice and chocolate.

–

I walked through the streets. There were no people. There was a post office and a bar, but no vegetables or bread, no living things. On a stone balustrade was a plastic bowl. Steam rose from it, like the steam in a laboratory. I walked on, seeing eyes everywhere. An unsightly child was sitting on some steps and making faces. Drapes welled out of an open window, like ectoplasm. I walked through Strega and arrived at the water, which gave off a familiar smell. Something mouldering and somehow tepid, like the night air in a church. On the dock, a semaphore was beating in the wind. From a crevice in the mountains, a ferry came gliding. It was a polished steel vessel with the name Skipper hand-lettered in yellow on its side.

I turned my face to the sky. The air tasted like iron, and I licked my lips. Everything was iridescent pink, except for the lake, which was black and gorgeous. The range gleamed and gleamed and the sky was clear. I sat on the ground and lit a cigarette. A young mother and her child were standing nearby. The boy lifted his hand to his face, as though to bat away an insect. The mother grabbed hold of his wrist. I took out the juice carton and drank it down in a single gulp. Then I ate of the stale bread. I tried to find the horizon, but it was hidden behind the mountains. I grew up by the sea, where everything was open planes. I took out my notebook and wrote down my home address, watched my name glow strangely on the page. I had always imagined the future otherwise. I was to work the perfume counter at the department store. I was to save my money and keep it in the bank under my own name. I was to move into a flat where other women were also living, free souls with jobs and love lives. But I did as they had asked of me. I liked being an obedient daughter. It felt like being held by a beautiful patent leather collar.

I let the notebook drop to my lap. The smell of the water was numbing me. I shut my eyes. For a moment the sound of the waves was crystal clear, as though they had washed into my head. Behind my eyelids something surfaced, a sequence from a film I’d seen. A taxi driving through a storm towards a red building. Cobblestones glinting in the rain. In a large hall, patterned textiles hung from the ceiling. A girl walked across the floor with a glass of water in her hand. She had a very anonymous face. Her hair was black and seemed to have been dipped in holy water. I addressed her, but she turned away.

When I opened my eyes, other girls my age were standing around and watching me. I blinked and blinked. The sun disappeared behind a cloud, then reappeared. Around me, the mountains suddenly seemed to rise up like walls. I looked at my hands, which were shaking. With one quick movement, I reached into my pocket and grabbed hold of the moonstone. I gathered my things and stood up. I nodded to the others. They nodded back. We walked to the cableway.

–

We flew forth above the valley. Motor hammering rhythmically, cables crackling. Around us were mountain clefts, insects, thistles. I looked to the ground, where women were at work. They were wearing cotton gloves and gathering something in large baskets. Wintergreen leaves with sturdy stalks. Autumn nettles, maybe. Mallow. I caught sight of a piece of granite beneath one of the wooden benches. Around me, the others were speaking ceremoniously with each other. They took hold of each other’s hands, tossed their long hair and laughed. Next to me sat a girl who seemed familiar. She had one of those faces that could easily serve as a screen for other people’s projections.

She said her name: Cassie.

I nodded.

I said my name: Rafaela.

The cabin rocked and I gasped. We had arrived. One of the girls pulled open the doors, and we climbed out. We looked around. On a tree trunk was a high-polished metal sign bearing the name of the hotel. We started to walk down the only visible road. It was a wide avenue, the forest billowing softly on either side. The road slunk through the landscape and then vanished around a bend. The dust whirled around our shoes. No one said a thing. All that could be heard was the dull, rhythmic crunch of gravel.

As if out of nowhere, the hotel appeared behind a very old black oak. Right away, I noticed that there was something wrong with its proportions. Against the backdrop of nature, the hotel looked like it was in miniature, like a doll’s house that had been handed down through the generations. The façade had at one point been painted a bold red that had faded and was now rather pink. As soon as we were through the gates, they shut behind us. The building sat in the centre of a manicured park. There were manicured bushes in even rows. There were whitewashed statues. We walked in a line with our luggage in our hands. The air trembled around us. We passed a fountain and a steaming thicket. There was a smell of dust and water and burned hair. All the windows were open. Music was coming from inside the building. Bright notes pinging the mountains. It was a classical piece that sounded as though it were being performed by an orchestra made up of deeply unhappy people.

I didn’t know why the place frightened me. It was a beautiful day, and everything was beautiful wherever I went. I stood still for a moment and tried to fill my lungs with the thin air. The fountain emitted a soft gurgle. I looked around. There was a clothesline and a bed of roses. There was an herb garden. There were wide stone steps leading up to the entrance. The front door was dark brown and seemed to have been cut from a single piece, as from an unnaturally large tree. Someone leaned forwards and knocked. I shut my eyes briefly, as though to hide. When I opened my eyes, I was looking right into a grave face. In front of me stood a woman with a duster in her hand. I wanted to laugh but didn’t. You’re here, she said. She was dressed in a black suit, the name ‘Rex’ embroidered with a silvery thread over her heart. She studied us with half shut eyes before moving aside and letting us in.

We stepped into the dusk. The music was louder here. The floor vibrated beneath our feet. I wanted to cover my ears, rest my forehead against a doorframe, and shut my eyes. The room looked like a scene from some blood-soaked ancient drama, where grave women in draped dresses moved across a stage, knives in their hands. Somewhere on the other side of the set, a chorus shouted its lines about shipwrecks and revenge and murdered daughters. I looked up. Through the dusk, I glimpsed a vivid mural on the ceiling. A stormy sky with scudding clouds, gold accents, and wild horses. All the walls appeared to be red. The thick curtains were drawn and didn’t let in any daylight. The lobby’s only illumination was a pair of silver candelabras on marble pedestals set far apart in the room. It could just as well have been a night with a darkening moon. I clasped my hands and looked around.

At the reception desk, a woman was sitting behind a pile of paper. She was wearing a formal suit dress with a figure-hugging jacket. She looked like a secretary. Or rather, she looked like an actress playing a secretary. We were led up to the desk and had to give our full names, so that she could tick us off a typed list. Over her heart was an enamel brooch on which the name ‘Toni’ was written in italics. She handed each of us a slip of paper with a number on it. The hotel’s purple stamp glowed against the white page. I got number seven, which seemed to be a given. When she handed me my paper I happened to curtsy, as if out of old habit. Surprised, she shook her head. She smiled, I blushed.

I ran my hands through my hair and turned around. A woman in a housekeeping uniform came up to me. Her gaze was evasive but friendly. She handed me a basket made from plaited plastic filled with cotton balls and shampoo bottles and hand soaps shaped like fruit. Over her heart I read the name ‘Costas’ on a handwritten paper tag fixed to her apron with a safety pin.

The moment the last of us had received our slip, the music came to a stop. We gathered in the middle of the room. Rex drew the curtains aside, and golden cascades of afternoon light flooded the room. Under our feet a marbled linoleum floor gleamed. The marble wasn’t marble, but hardened oil. Next to me was a bouquet of flowers on a sideboard. Carnations, green, reaching for the ceiling. The vase was knobby and seemed to have been made by a very young child. Clumsy hands that had tried to shape something beautiful. The colour reminded me of cough medicine, I could taste it in my mouth. I looked at the other girls. For a moment they all had green eyes. It must have been because of the sudden shift from darkness to light and all the red around us, something to do with the contrasts. We stared at each other, anxious but also smiling. Their irises seemed to be seeping through the whites of their eyes and down their cheeks, only to evaporate there. I lifted my hands to my face. It felt damp.

As if on cue, we cupped our hands over our eyes. We stood like that for a while, breathing deeply. Something seemed to pass through the room. It sounded like a sack being dragged across the floor. We let our hands fall and looked around. The spell was broken. I counted nine pairs of eyes blinking fast, as if in shock. I turned to the mirrored wall on the short end of the lobby. My eyes were black again, as usual.

I broke away from the group and walked alone up the stairs, through crimson and soft-lit corridors, all the way to the seasonal workers’ dormitory on the second floor. The beds were lined up in even rows and looked like bunks. On each mattress was a black uniform dress with shiny buttons. It could just as well have been the dormitory of a penal institution. By the window was a bed on which the number seven was painted, white on dark wood. The bed was made with rough sheets. The hotel’s emblem was embroidered in purple, surely by hand. I set my suitcase on the floor and went up to the window. Everything was sparkling clean. At first, I thought the windows were glassless. I opened the hasp and leaned out. The air was hot but fresh. I couldn’t get enough of that taste of mountain and sun and chlorophyll, my lungs drank and drank. Down in the courtyard, some of the girls had gathered. I think they were smoking under the cover of a bush, or they were discussing something secret, something that demanded seclusion and shade.

Beyond the park, the forest spread. There was no horizon, only a curtain of bark and trunks. Mountains rising to the sky and disappearing among the clouds, which were thin and wispy, as clouds are in the mountains. Autumn was attacking tree after tree. Soon everything would be a flaming yellow. A hot and consuming light would settle upon it all. We were to walk out into the forest. We were to pick berries and make jam. We were to air out our coats in the park. I lifted my gaze. From the treetops an image emerged. As through an oval portal, I saw the contours of a structure. The building was very old, built of rough-hewn stones in a simple pattern and surrounded by a small but lush garden. I saw red apples hanging in the trees. I saw bed linens drying on a washing line. I saw that the heat had laid itself upon the herbs and burned them. I thought: A convent. I took out my sunglasses and went back to the others.

–

We gathered in the staff refectory. They treated us to cherry cordial and almond cookies. We opened wide and swallowed. I felt ashamed of my shoes and my dumb face. I took a seat in the middle of the room, next to a potted golden cane palm. It smelled dry and hot. My shirt gleamed against the Paris-blue glaze. I have always believed this: hiding is easiest when out in the open, when you unveil yourself as one would a statue in a rural square. Someone whips off a large black velour shroud with one quick gesture. A murmur ripples through the crowd, but no one is looking at the statue. They are all watching a point behind it, something shining in a shop window, a jewel.

At the other end of the room, a group of girls had gathered. They were laughing and touching each other’s hair. One of them was talking more than the others. From her hands, a bright light radiated out into the room. I was surprised that I hadn’t noticed her until now. She was wearing black velvet trousers and a pale red silk shirt. The shirt was wrinkled and the sleeves rolled up. Her nails were a shrill red, but she had no makeup on and shadows under her eyes, which shone with a deep, magnetic darkness. Her hair was thick, almost black, and dishevelled. She had tried to gather it in a large hair clip made of tortoiseshell. I allowed my eyes to rest on her collarbones. There was something soiled but sophisticated about her, and I loved her right from the start.

The hours passed. I sat by my plant, listening and looking. The low evening sun found its way through the open terrace doors, like the glow from the oversized lamp, placed somewhere in the forest beyond the gates. The light beat like a flame against the curtains, which billowed and billowed. I ran my hand over the fabric of my shirt. A smell of sweat and spice came from my armpits. It’s humiliating, I thought, to live in this body. Someone ran by in the corridor and I looked to the door. Out of the corner of my eye, I caught a flash of patent leather shoes. No one came. I turned to another girl with a comment, and she responded. Something about parents. Something about sports. A brief and boring exchange. I leaned back. One of the girls walked off and stood by the window. The evening was soft and mild. Seemingly out of nowhere, a hard and beautiful laugh escaped the throat of the girl with no makeup. A confused silence settled over the room before the others finally joined her in laughter, though tentatively. I heard my own mouth give a short laugh as well, before it shut.

The door was flung open, and Rex entered the room with her scent of hair oil and patchouli. She looked at us with disgust, as through a crystal ball that was showing us for who we really were. She took out a cigarette and lit it with a candle. Using the smoke from the cigarette, she wrote ‘Rex’ in the air for us, mirrored and with rounded letters. The name lingered for a moment before it was dissipated and devoured by a gust of wind from outside. She cleared her throat and started reading the hotel rules from a sheet of paper. Her voice roared through the room in a far too steady rhythm, as though the voice came not from a person but a machine. No men in the dormitories or in the staff refectory. No leave, unless in the case of a death in your immediate family. She looked at us: Dead mothers, dead sisters, that’s it. Everything that happened at the hotel was to be treated as confidential. We value loyalty here at the Olympic. All telephone conversations were to go through the permanent staff. We can facilitate a call home, if need be, but we would rather our girls avoid devoting themselves to homesickness. Transgressions would result in immediate termination, without pay. You’re seasonal workers, that’s just the way it is. Any complaints are to be filed with me personally. She looked at us, wondering if we had any questions. We shook our heads. Behind me, I heard someone’s earrings rustle. Rex lit yet another cigarette, took a deep drag, and stared with measure through the terrace doors. She left the room with a nod, and we breathed out.

I got up and stood next to the girl by the window. The others stayed in their seats, as though paralysed. I said nothing. I pressed my forehead to the glass. Outside the terrace doors, the park lay in total darkness, but was apparent in its scents. It was a damp night. The dew spread and drowned everything it could reach, intensifying the smell of earth and honey emanating from the plants. The harvest moon appeared in the sky. It was silver and iridescent, like an opal. One wanted to take it in the mouth and place it under the tongue. One wanted to see it spill its milk across the earth, until all was moon. In the middle of the lawn, a red ball lay gleaming. Something glow-in-the-dark in the plastic was making it supernatural. The wall clock in the dining room struck ten. A smell of almond and cherry rose from my hands. A sweeping sound came from the corridor. The woman who was called Costas appeared in the doorway. She fixed her gaze on a point behind us, something she was seeing with her inner eye. She said: Ten minutes until lights out. We looked at our hands. Someone whispered something. Someone dropped something. We walked to the dormitories.

I sat with my nightgown in my lap and waited. I didn’t want to show my naked self to the others, I don’t know why. The moment the electricity was shut off, the dormitory was swallowed by a surging darkness. Everything around us disappeared, but you could sense the park outside the window, you could sense the mountains. I heard someone strike a match against the wall. I inhaled the smell of fire and sulphur. The room was still dark but by the window was a flaming orb, the soft glow of a storm lantern.

–

The night air in the dormitory felt sticky on my lips. I ran my tongue over my teeth. Overhead, someone was running across the floor. I looked up at the ceiling, where red mould seemed to be spreading in a bad way. Around me, the others were sunken in a communal sleep. I saw their hair sweeping across the pillows, like black shawls. They were sleeping like children, hands clasped, mouths open. On the chairs between our beds, their clothes lay folded in tidy stacks. I looked at the objects that belonged to them. A razor on a nightstand, a bottle of aspirin. Perfumes and matches and sewing kits. I pressed my teeth into my knuckles until my knuckles bled. It seemed impossible to escape this collective burial. I longed for my own room, the locked door, my little cell. I was a lonely person, I had been alone all my life. One is alone even in the company of one’s mother. One speaks, and it echoes inside her.

I turned my hands to the ceiling and shut my eyes tight. All my sleepless nights arose in me, as if somebody were emptying something out inside me, a sweet drink with belladonna, as from a pipette. I fell asleep and woke up in the same motion. I opened my eyes and saw a blue haze drift in through the curtains. I recognised the milk of dawn and lifted my hand. I got up and walked barefoot across the floor. I opened a window. Out there, the park lay empty and thick with dew. Everything was fresh, but also seemed old. The harsh light of morning washed over me like grace. The morning air seemed to carry with it a particular dampness, different to any I had known before, as though it had drunk of a holy decoction made from green leaves and wet stones. I leaned out the window, greeted the rhododendrons, the boxwood, the black moss, dug my fingers into the woodbine growing on the façade, let them rest there for a moment, hidden by all the green.

I took great care making my bed, smoothing the cotton with my hands. I went to the bathroom and washed my face with cold water and soap. My eyes burned, and I blinked. The bathroom was decorated like an English garden. Monstrous, artificial plants crawling along the walls and floor. A glassed-in watercolour of a fountain. On the rim of the bathtub sat small bathing beauties made out of porcelain. I hated these porcelain figures, because they represented everything that was wrong in the world. I’d read a pamphlet on Marxism, which I’d been given at the People’s House one night, and after that I had cultivated a violent hatred against everything small and everything pleasant. I hated the ornate and the diminutive. I hated dessert spoons and cigarette cases and compact mirrors. I hated my dress and its pleats. I hated sitting on a chair with my legs crossed.

I sighed. Sank to the bathroom floor like a cloth someone had dropped. It’s a strange thing to be in the mountains when one wants to be by the sea. I sat like this for a long time, heard the pipes working, heard the water flowing through the building as though to drown it from within. I got up and went back to the dormitory, put on my uniform. It gave off a strange smell of plastic, of industry, which was probably meant to camouflage the uniform’s true smell, namely the smell of mould, of some dank basement. I buttoned my jacket and straightened my skirt at the waist. In the mirror, I saw a uniformed and anonymous person, face empty and uninteresting. This was a great relief. I didn’t have to show them my true face. It was enough to show them the uniform’s face, a face for a decent life, an orderly life. Sometimes I wore my mother’s old dresses. I had a red rayon one that made me look like an assistant. I had a dove-blue cotton one that made me look like a government employee. In the uniform, I appeared to be a competent woman. I gave myself a formal nod, gathered my hair in a low bun.

I ran my hand along the wallpaper in the corridor. It was moist, like skin and gave off a faint saltwater smell. I opened every door I came by. I found a broom closet, where bottles of cleaning materials stood next to large packs of sponges among messy piles of scouring rags and steel wool. I felt a sudden urge to sort everything by colour, fold the rags into perfect squares. The wall-to-wall carpet was like a red river and consumed all sound. At the end of the corridor, hidden behind a thick drapery of imitation velvet, I found a door. Behind it were red-painted stairs. Whirling in the air around me was some sort of powder. There was a scent of moth repellent, slaughterhouse. I couldn’t see where the stairs led, but the fear in my chest grew as I considered this red colour, like when one walks into a room and is struck by the thought that it is inhabited by evil spirits. On the chairs sit ghosts, drinking water from drinking glasses, opening fruits with their hands. I leaned in so I could look up, but above there was only an opaque penumbra.

The stairs that led down to the lobby were wide and lit up day and night by a row of pink-shimmering lamps shaped like shells. It gave the impression of walking through a bordello, a place where night was eternal and everything took place under the shield of darkness. Unusual scenes in which a girl bends forwards in an oversized wedding dress. Unusual scenes in which a grown woman is dressed up as a confirmand. I walked slowly and with control down the stairs, pretending to be making an entrance at a debutante ball, waving with reserve to my many admirers. Behind the reception desk, inside a felt-clad alcove, the room keys hung in a row. Numbers one to seventeen, written in red in roman numerals on oval tags made of dark, thickly lacquered wood. They seemed to be ordered by some incomprehensible system, an order other than that which is given.

I stood and flipped through the register. Empty page upon empty page, not a single guest since the end of June. At the very front of the book, the pages were so dense with names they spilled into the margins. The guests seemed to have come from everywhere. There were names of the rich, but the kind of rich who had inherited their fortunes, as though money were not money but inner organs, something already vested, long before that first morning, that first light, when one, tender and unseeing, met the world. Mothers who birthed blue foetuses with mink stoles around their necks. Fathers who sat fuming on the stone staircase in the garden, after their wife had insulted them by giving birth to a daughter. And everywhere these chambermaids and housekeepers and subjugated women.

I slammed the book shut with a sort of rage. On my hands were marks left by my front teeth. The night’s endless grinding. I must have been seven the last time I slept the whole night through, a deep and dreamless sleep free from worry, a small child’s corpse tucked into its coffin. I went to the staff refectory. Drank coffee, ate a slice of bread. I held the cup with both hands. It was a porcelain cup with the hotel’s emblem. Someone had placed a piece of rock sugar on each saucer. I stuffed the sugar in my mouth and let it melt there. My lips became sticky and tasted sweet. There was a clatter in the corridor outside. Toni, Costas, and Rex had already been working for hours. I had heard them walking across the gravel pitch. I had heard them slamming the doors and throwing the windows open, caught the scent of cigarettes and coffee and newly washed sheets. I stood in the terrace doors and looked out over the park. The ball was no longer glow-in-the-dark, but matte.

–

We were nine young women doing seasonal work in the mountains, or nine young women put in safekeeping on the backside of the mountain, or nine young women who watched their hands being put to work, watched them lift starched fabrics to their face only to let them fall to the ground, watched them pour strong wine out of large carafes, like the hands of a statue, right into the parched earth, as though to sate it. We came from various places, but were of the same age and mind. None of us wanted to become a housekeeper, and none of us wanted to become a wife. We had been sent here to earn our keep, to become people of society. We were daughters of hardworking mothers and invisible fathers who slunk along the walls. We were in the mountains because someone had sold something. It could have been silver, it could have been heirloom gems. It cost money to send your daughters to the mountains. Daughters needed tickets, visas, milk chocolate. Daughters needed amulets. This could be a gold-mounted box inlaid with clear plastic stones, where she, the daughter, could store the only treasure she had ever saved: a milk tooth on which the blood remained.

Our parents were all deluded about the fact that the world had changed and would not go back to being what it once was. They did not believe in a future without the good woman and her duties. They wanted to prepare us for a life where we would care for child and home, where we would stay with one man, no matter who he was, where our hands would repeat the same movements. At the hotel, our hands always repeated the same movements, but this was no place for good women. Our parents had imagined the hotel to exist in another era, that it was in fact possible to send us there, to a place where no time had passed, as if we could slip behind a curtain, where the evil steam of reality could not reach us.

The hotel, which was in an isolated valley, surrounded by black mountains reaching out of dark and humid vegetation, by a small blue lake with icy water, had once been a famous and much-frequented place, a place for wedding parties and winter sports, a place that seemed magnetic, where it lay sparkling red among all the green. No one remembered when the hotel had begun to change, when the place had begun to seem repulsive to all healthy people, as though it possessed an inherent power, something fiendish and sick that kept people away. A suspicion was that a poisonous plant had begun to grow many years before, a plant that was now in full bloom. Someone had planted rosary pea. Someone had planted henbane. There were rumours that it was the nuns. The convent had been where it was for all of human time. The nuns had walked the same paths, drawn water from the same streams, dressed in the same starched cotton. They had lived this life, dipped in formalin and embalmed in the face of eternity, right up until the day the hotel was built.

The conflict between the nuns and the hotel staff was deep but unarticulated. One had never spoken ill of the other. One had never taken action. One had seen the other, one had nodded. The hotel had appeared one summer, as if out of nowhere, like something demonic. Demonic, not because of the sin inhabiting it (women in pink furs, men with large hands, small bottles of strong drinks), but because of the way it situated itself in nature, like a piece of meat, a primal cut, something animal and dripping. The nuns spoke of the hotel in hushed voices. They never used its real name, they never said: Hotel Olympic. They said: Il Rosso. It was said that they walked by with bowed heads and rosaries in their hands. They prayed, they counted. It was said that they suffered and that one left them to their suffering. This happened many years ago.

It was a different time when we lived there. The hotel was no longer demonic, but had instead become a relic from a long-buried era. One might imagine a hotel as a lively place. One might imagine clatter in the kitchen and clinking glasses, the smell of lilies and something metallic, a tray set with cups and coffee. One might imagine a hotel as a place for people, but that wasn’t the Olympic. At the Olympic, the clatter and smells were enclosed in the walls, like a haunting or a flickering memory. Everything was built on a grand scale. The ballroom was enormous and the suites facing the park seemed endless. One could stand at either end and call out to each other, as from a mountaintop. In the kitchen were three long and wide workbenches, where it was clear that there had once been intense activity. One could picture it. Old-fashioned food laid out on white tablecloths. Pineapple ice cream and oxtail soup. Vile things to stuff in the mouth.

It happened that I leaned against one of the large industrial cabinets, chewing on a carrot. I could conjure up whole scenes in the room before me. Large platters of meat and vegetables. People in white shouting to each other. Pretty girls on the waiting staff. Behind this hologram was the reality, a hotel business in utter decay. In one corner, Costas was cutting celery into small cubes. Alba stood next to her, blanching tomatoes. It was all very dull and unglamorous. Scenes from a monotonous and unbearable life. The grey light fell across Alba’s face, as if to insult it.

It happened that I walked through the woods to consider the hotel from a distance. I looked out over the bitter waters of the Alpine lake. On the other side, the hotel rose out of the forest, red and immovable, a monument to long-dead maids and their shrouded knowledge.

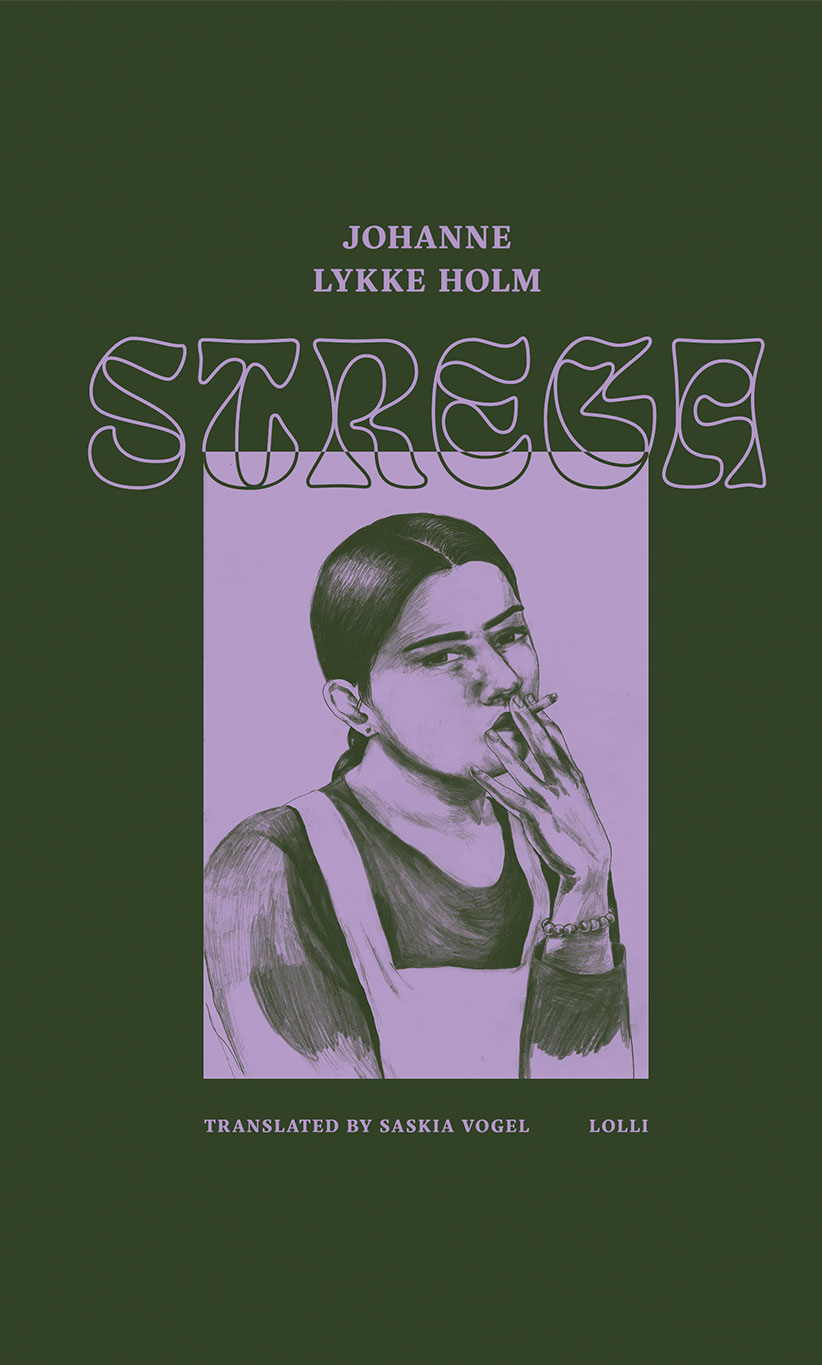

Image © J Swanstrom

This is an excerpt from Strega, out on 1 November 2022 from Lolli Editions.