I was in the waiting room. Then I was in the examination room. There was a chair, and another chair, and a hydraulic doctor bed. Sit down, the doctor said. I didn’t know where. Not on the bed, he said. I sat on a chair.

‘I think I have a concussion,’ I said.

‘Why do you think that?’ the doctor said.

‘My nephew hit me.’

‘He hit you?’

‘In the nose. Then in the back of the head.’

‘How old is he?’ the doctor said.

‘Fourteen,’ I said.

‘Okay,’ he said, ‘take off your shirt.’

‘Really?’ I said.

‘Sure,’ the doctor said. I unbuttoned my shirt. He shone a light in my eyes.

The light was on the end of a cone. The cone was set at ninety degrees on the end of a metal rod. It looked like a thing dentists use for looking at mouths.

‘No concussion,’ the doctor said. It didn’t seem like he could tell that just by shining a cone in my eyes.

‘Looks like you have a little eczema here, though,’ he said. He pointed to my chest then spun away in his chair.

–

I looked down at myself. There was a red patch, and what looked like a slightly raised piece of dead skin in the centre of my chest. Just to the right of where I assumed my heart was.

‘Okay,’ I said.

‘Don’t worry,’ he said, looking at his computer, ‘very treatable. I’m writing you a prescription. For hydrocortisol cream.’

‘Don’t you mean hydrocortisone?’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘hydrocortisone. That is what I said.’

–

My brother’s wife, when I was back at the house, said I shouldn’t have provoked her son.

‘He’s very sensitive,’ she said.

‘What?’ I said. ‘I didn’t provoke him.’

‘He loved your dad,’ my brother’s wife said. ‘They had a real connection.’

‘I don’t see what that has to do with anything.’

‘Are you really going to wear that outfit?’ she said. I was wearing a T-shirt with lots of Phils on it: Phil Leotardo, Phil Neville, the Philippines, the concept of ‘Philanthropy’, Philadelphia (the spread), the London Philharmonic, Prince Philip.

‘What?’ I said. ‘No. I am going to wear a suit.’

‘It has a stain on it. You can’t wear that.’

‘I am going to change,’ I said.

My brother walked into the kitchen and kissed his wife on the forehead as she walked out of it. He started doing something in a cupboard.

‘You should wear the Phil T-shirt to Dad’s funeral,’ he said.

‘I am going to change,’ I said, and left the room.

–

I looked at myself in the half-steamed bathroom mirror. This was the house I grew up in.

The doctor was right about the skin on my chest, just to the right of where I assumed my heart was. It looked all weird.

I picked at the skin. It came away painlessly.

Just a little at first. It made a thick and translucent white flap. I flicked at it with my fingernail. I pulled at it. More pulled away like damp paper. Over my left nipple, then right up to my armpit.

It started to sting a little like it was meant to stay on. I stopped tearing myself. The skin just hung there.

Then I kept going.

I couldn’t walk around with half my chest hanging off me.

–

Once I’d torn it mostly off, I had an alarmingly large piece of skin in my hands. I looked at it.

It was me but losing its shape, still slightly ridged where it had run over my ribcage.

I looked at my body in the mirror.

There was a long rift where I’d removed the dead skin. It poked outwards, up the side of me, almost imperceptibly, like the unfindable edge of a Sellotape roll.

I didn’t know what to do with the skin that had come off. I couldn’t leave it in the bathroom bin where my brother or his wife would find it. And I didn’t want to flush it, either.

I thought about putting it in my pocket and taking it downstairs and wrapping it in a plastic bag and disposing of it secretly. But that felt insane. And I didn’t want to get caught doing it.

I dropped the skin into the bathtub. It made a slap sound. I turned the showerhead on all the way. I pointed it at the skin. After a moment it began to break apart, as if decomposing, and the tiny pieces of it were carried by the spiralling water down the sloping porcelain, down into the plughole.

–

After the funeral, at the wake, which was at the house, my nephew apologised for punching me.

‘I’m sorry for punching you in your head,’ he said. ‘No problem,’ I said.

‘I just get so angry sometimes,’ he said.

‘Right,’ I said.

‘Don’t you?’ he said.

I poured myself more wine from the bottle I was guarding from everyone else. The new skin was tender under my shirt, under my jacket.

–

The living room was large but full of mourners. My uncle by marriage was holding court on refreshments.

‘Yes, I borrowed it from work,’ he said. ‘From the work canteen.’

He was talking about a large metal urn that stored and dispensed near-boiling water.

‘I thought a lot of people would want tea,’ my uncle said, ‘and that this would make it easier.’

‘It must have been hard to get here,’ I said, ‘with all the hot water in.’

‘What?’ he said.

‘Imagine if it spilled on someone,’ I said. ‘They’d get all burnt.’

‘No,’ he said, ‘you don’t transport it full. That’d be dangerous.’

‘That’s what I’m saying,’ I said.

‘What are you doing for work at the moment?’ he said. ‘Still writing? Like your parents?’

‘Yeah,’ I said.

‘And the money’s alright? I read an article about how books don’t make money anymore. Barely any of you make any money.’

My brother walked over. He was holding a glass of wine and a beer.

‘I see you have two drinks,’ I said, to him. ‘Nice.’

He tried to hand the beer to my uncle, who put his palms up and made a goofy face, then mimed driving a car.

‘Thanks for apologising to your nephew,’ my brother said, to me.

‘I didn’t,’ I said.

‘He really appreciated it.’

‘I didn’t apologise. He apologised to me.’

‘Sure,’ my brother said.

‘Hey,’ I said. ‘Some of my skin came off earlier.’

My brother was a plastic surgeon. That was his job. ‘What?’ he said.

‘In the shower. Like a reptile.’

‘Your skin came off?’

‘Like a reptile,’ I repeated.

‘That sounds like eczema. You should see a doctor.’

‘You are a doctor.’

‘I’m not a skin doctor.’

‘You are a skin doctor.’

‘No, I’m not. I’m a surgeon. I’m not looking at your eczema skin.’

‘I saw a doctor today,’ I said, ‘and he gave me a cream.’ I tried to pour myself more wine from my bottle but it was empty.

‘So use the cream,’ my brother said. I walked away to get another drink.

–

Back in the kitchen, a neighbour from down the road said it had been a beautiful ceremony.

‘That was a beautiful ceremony,’ she said.

She was older than sixty and wore purple all the time.

Even to funerals.

‘It was?’ I said.

But she thought I was just agreeing. ‘He would have loved it.’

‘He would have?’

‘He would have found it very moving.’

‘I thought he might have found it disappointing,’ I said, ‘being dead.’

‘Yes, he would have found it very moving,’ she said. ‘He was a very emotional man. A true artist.’

I thought about my father in the audience of my brother’s school flute recital, holding a biro and the photocopied programme, ticking off each act as it finished.

I thought about my father in the audience of my brother’s school prize-giving, slumped. I thought about him sitting up, suddenly, when a small girl, maybe nine, won an award for ‘dance’. I thought about him saying loudly, incredulously – loud enough for parents to shush him – ‘Darts?’

‘You knew him pretty well,’ I said.

‘We had a connection,’ she said. ‘He was a true artist.’ I looked around for a different conversation.

‘And so kind,’ she said, ‘staying with your mother. After everything.’

I drank the last of my new glass of wine. I put the glass down on the counter hard.

‘Listen, you stupid purple bitch,’ I said. ‘Shut the fuck up about my dad.’

–

I woke up hungover in my childhood bedroom. I was still wearing my shoes and trousers.

My white shirt had quite a lot of blood on it. My head hurt under my face.

I took my shoes off and went downstairs to make coffee.

My brother’s wife was in the kitchen already.

‘Coffee?’ I said. I gestured at her with a mug. She didn’t say anything. She just made a sound and left the room.

My brother walked in as she walked out. He kissed her on the forehead as they passed each other.

‘Got some blood on you,’ he said.

‘Make me some coffee.’

I sat down at the breakfast island in the middle of the kitchen. The tea urn was gone. But there were glasses and mugs everywhere. The foily remains of wake snacks.

I took my cigarettes out and lit one. ‘Jesus Christ,’ my brother said.

‘My head hurts,’ I said.

‘She got you good,’ he said.

‘I should have hit her back,’ I said.

‘As if you could,’ he said. ‘She made you look like a little bitch.’

‘Yeah,’ I said.

‘You are a little bitch,’ my brother’s wife shouted, from another room.

–

I heard my brother and his wife leave to get some air or something. So I called my girlfriend.

It rang once. Then the line went dead. There was no option for voicemail.

I let myself count the days in my head. I had last seen her three weeks ago tomorrow.

Maybe she had blocked my number now.

The wood felt cold and crumb-covered against my forehead.

–

My brother drove me and his wife to our mother’s nursing home. My brother’s wife made sure she sat up front so I sat in the back of their car, which was small, but new, and expensive-seeming.

‘How was the funeral?’ my mother said, from her chair, which was disgusting.

‘It was beautiful,’ my brother’s wife said. ‘It was a really beautiful ceremony, Rebecca. Everyone said so.’

‘I’m so glad,’ my mother said.

‘Have you got everything you need, Mum? Do you need us to bring anything?’ my brother said, louder than necessary. My mother ignored him.

‘What happened to your face?’ she said.

‘Cheryl hit me,’ I said.

‘Why would she do that?’ my mother said.

‘I was defending Dad’s honour.’

‘He called her a stupid purple bitch,’ my brother said.

‘Shut up,’ I said.

‘Oh, no,’ my mother said.

‘I didn’t,’ I said.

‘Oh, no,’ my mother said.

‘And my skin is peeling off, Mum,’ I said. ‘I’m very frightened.’

‘What?’ my mother said.

‘Nothing,’ my brother said. ‘He is just joking. He has some eczema. He is just joking.’

‘I hope you didn’t hit her back,’ my mother said.

‘I got her good. Spark out,’ I said. I mimed a jab with my right. ‘Cheryl’s in the hospital.’

‘Oh, no,’ my mother said.

‘No, he didn’t,’ my brother’s wife said. ‘He’s just trying to upset you. He didn’t hit her.’

‘She’s messed up,’ I said. ‘She’ll never look the same.’

‘Oh, no,’ my mother said.

–

‘Maybe we should just kill Mum,’ I said, in the foyer of the nursing home, as we were leaving. ‘No parents, no rules. Clean break.’

‘Shut up,’ my brother’s wife said.

‘What did you say the advance on your book was?’ my brother said.

He meant my second book, the book I had told everyone I was writing, and got paid an advance on.

I had told everyone it was about an elderly gardener. The gardener lives near Chernobyl, in Soviet times.

The gardener dies because he’s so old. In the middle of the gardener’s funeral rites, the nearby power plant explodes. The funeral is abandoned halfway through.

The gardener becomes a dybbuk, which was a kind of Jewish ghost I’d seen in a movie. He has to wander around the Earth endlessly, gardening or something, until something gets sorted out.

That was as far as I’d gotten. I hadn’t actually written any of it yet.

I had tried. But every time I tried I just didn’t. ‘Fifty five thou,’ I said. ‘Clean, non-sequential bills.’ ‘Fucking hell,’ my brother said.

‘That’s wonderful news,’ my brother’s wife said, ‘congratulations. You won’t need to be in London. You can help get the house in order. For the sale.’

‘Yes, good idea,’ I said, thinking about not having to pay rent anymore.

–

It was the autumn and there were leaves everywhere. I decided to go back to London to get things. On the train I sat facing the wrong direction and looked out the window. The air was full of rain. I was carried backwards into it.

In my flat the furniture was still there. The sofa, the television, the stereo, the gifted soft-furnishings.

But when I opened the wardrobe to get a clean jumper it was empty. Or, two-thirds empty. All my girlfriend’s things had disappeared. Her dresses, blouses, skirts. Her floating light-fabricked trousers. Her multiple, heavy winter coats. I went to the dresser and checked the drawers that belonged to her.

But they were empty, too. All that was left was lint, and the decrepit sprigs of lavender she believed would ward off moths.

Then I noticed the bookshelves. They were also mainly empty. So was the bathroom. All the stupid and expensive houseplants had disappeared.

I was surprised at how few of the things we owned together belonged to me. There were outlines of dust all around the places her things used to live.

The air smelt different somehow.

I looked around for a note or something. But there wasn’t one. So I tried calling her phone again and it rang once and then went silent.

I went out onto the balcony for a while. The sun was setting grey.

–

When I woke, it felt like someone was watching me.

I sat up in bed for a second. Then I turned on the lights. But there was nobody in the room. And the curtains were closed.

I noticed that in my sleep I’d built a person out of pillows next to me. Maybe so it felt as if she was still in the bed.

I could feel my heart pushing my chest.

When I couldn’t get back to sleep I dressed and had a drink. My girlfriend had taken some of the wine but left the spirits. After that I felt a bit better.

I started packing possessions into the suitcase she hadn’t taken. It was the ugliest one. We had named it ‘Ugly Green’.

By the time dawn was done I was ready to leave. I wrote an email on my phone to the estate agent saying we were vacating the flat; that they could dispose of the remaining contents, at our expense, as they saw fit.

Then I tried calling her again. But it rang out.

I rolled Ugly Green to the door. I turned around and began to wipe the dust outlines of her possessions from the shelves and counters and other furniture surfaces. But then I decided I did not feel like it. So I gave up.

The train back to the house was half-filled with commuters, in various states of rained-on, all umbrellas and ugly laptops. They thinned out as we got further out of the city, until I was alone, in the train carriage, in the countryside.

–

From the outside, once I was back at it, the house looked very empty.

The plants around it seemed to have gotten bigger.

There were vines growing up one of the walls. They were almost touching the glass of a ground floor window.

My key was loud in the door. Nobody shouted hello.

–

In the bathroom, I picked at the skin on my hand. It felt dry and funny.

The skin pulled upwards, from my wrist, all the way from my palms and fingers, and then across the back of my hand. I just kept pulling, until it had come away from all my fingers and shifting hand veins. The skin came away in a single piece. It didn’t hurt. I looked at it. It looked like a glove of myself.

I threw the skin into the bathtub. I turned the showerhead on and aimed at the skin and watched as it disintegrated and was carried down the drain.

My brother and his wife were back in their big and increasingly valuable house in London. So I was alone in this one.

It was mid-afternoon. I got drunk. Then I went to bed and slept dreamlessly.

–

It was almost afternoon again. I was not sure how I had slept so long.

I wrote a message to my brother and his wife to confirm that I would be living in the house, ostensibly to help clear it out for the sale.

I did not want to do that. But saying it would make them feel okay with me living in the house.

After I wrote that message I looked at Twitter. My girlfriend had a new story out. In Guernica. She still had me blocked. But the story was all over everyone else’s Twitters. So I saw it anyway. Everyone was calling the story excellent, dark, funny, astute, etc.

I opened my laptop to look at it on there. I scrolled all the way to the bottom.

I didn’t recognise her new author photo. Her hair was shorter than it was. Beside the photo it said: Kei Kagirinaku is a writer from London.

Downstairs, I heard the television say: the magnetic North Pole is moving increasingly towards Siberia, away from Canada. I didn’t remember turning it on.

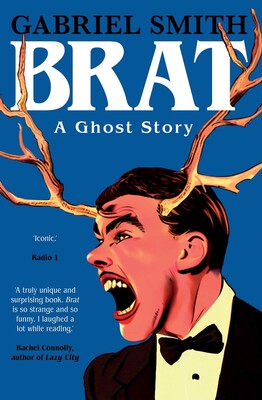

Image © Mathew Schwartz