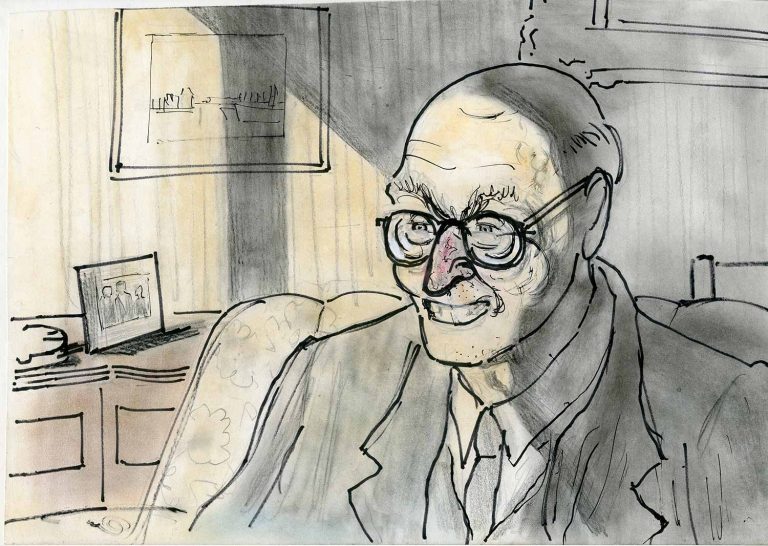

Jan Vegter was a Dutch artist and drawing teacher. He was born in 1927 in Voorburg, a small town in the outskirts of The Hague, and died there in 2009. After retiring in 1990, he created three series of drawings with handwritten captions. Two of them recalled his experiences of the Second World War, and the third was about his early travels to Paris after the war.

The second series, Hongerwinter en bevrijding (Hungerwinter and liberation) features eighteen drawings in a 32×41cm sketchbook, using a mixed technique of pencil, charcoal, drawing chalk and watercolour, and is set in Vegter’s home town of Voorburg, depicting his experiences and impressions of the final period of the Nazi occupation of The Netherlands. The province of Holland in which Voorburg is situated was one of the last regions in Europe to be liberated in the beginning of May 1945. It has been estimated that between 18,000 and 22,000 Dutch civilians starved to death during that last winter.

The story is told from the viewpoint of a seventeen-year-old boy, whose comments are frequently ironic, and sometimes distant. Vegter had an outstandingly accurate memory, usually drawing without any preliminary sketches, or without referring to photographs. The result is an accurate visual record of the time and, perhaps even more interestingly, a commentary on the numbing effects of war and starvation.

– Theo de Feyter

Voorburg, August 1944. The Allied advance from Normandy was slow to begin with, but after a short while it sped up. We moved the little flags on our map at home farther and farther east. ‘They have taken Paris!’ our family friend Piet shouted. He felt obliged to tell us that. ‘It will only be a few weeks now!’

And that’s what we all thought. Brussels fell, Antwerp fell. Allied forces crossed our borders on a Tuesday in September, and we couldn’t restrain our joy – one day of vibrant happiness.1 The day after that we became aware that we had cheered too soon. The Germans weren’t gone. The Allied advance slowed down, and then got stuck in the Betuwe2. Deadlocked. The landings in Arnhem3 were a disaster. We suddenly realised that winter was coming , and that we would probably be in a dire situation.

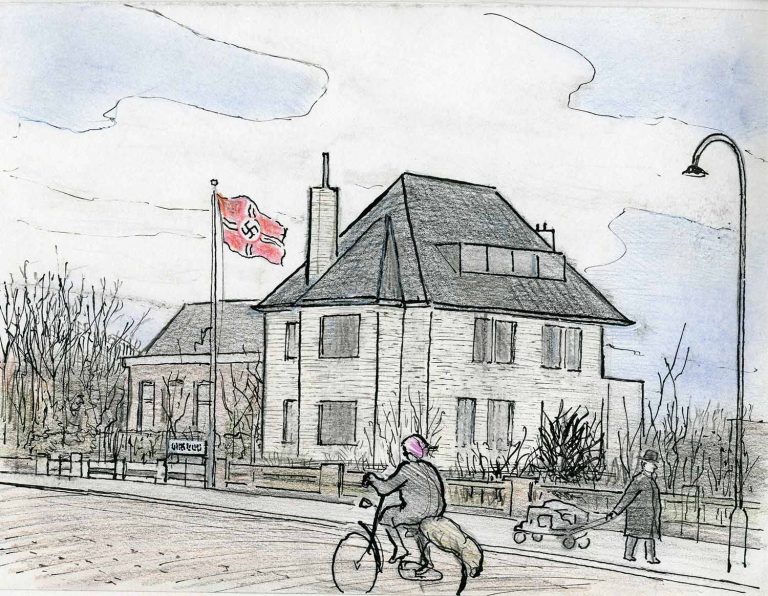

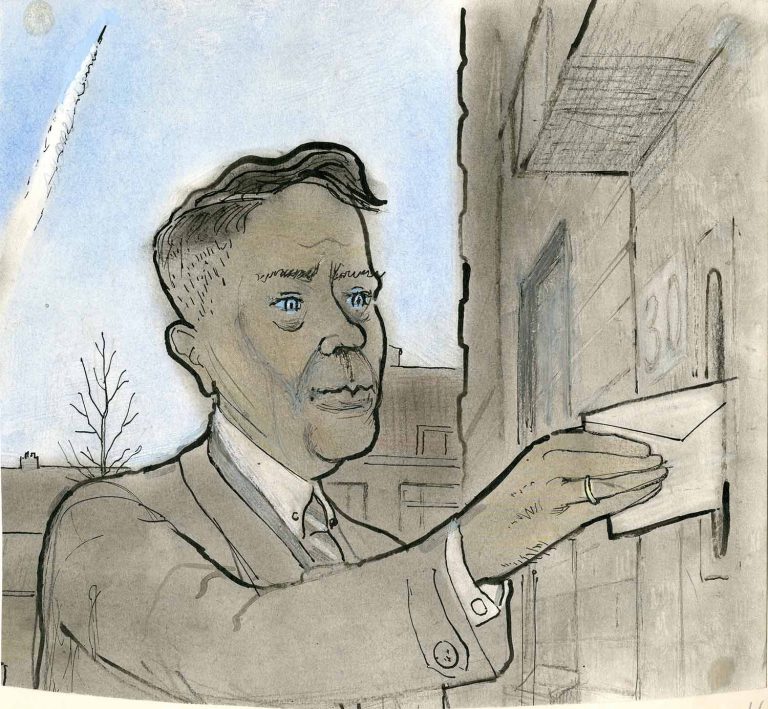

We hoped it wasn’t going to be as bad as we thought, but it was. We realised that the announced railway strike had a dark side as well. No transportation anymore . . . ‘nur für Wehrmacht’.4 Cars had been abandoned long ago. Anyone who drove a car was under suspicion. So everything with wheels – bicycles, baby carriages – was of vital importance. Whoever was dependent on official food supplies couldn’t survive, and fuel was even more precarious. It wasn’t the problem of the Ortskommandant 5 in Oosteinde, though. He had food and a car. And a flag!

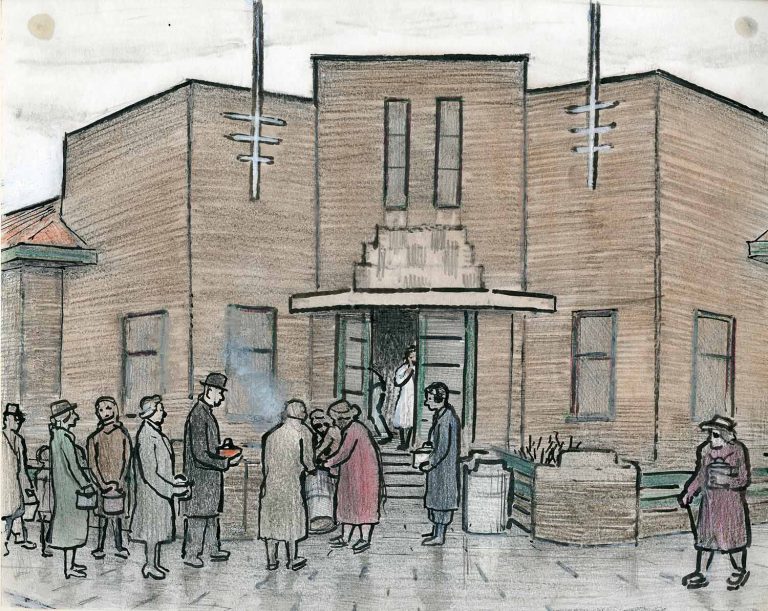

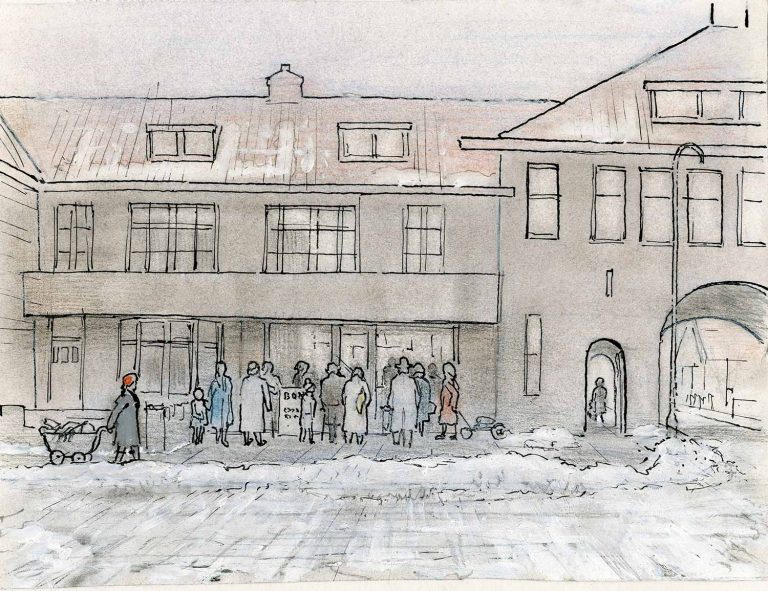

Many respected Voorburgers tried to stow something away when queueing in Plaats van Middendorp with their little pans to receive some soup. It wasn’t much of a soup, but it was better than nothing.

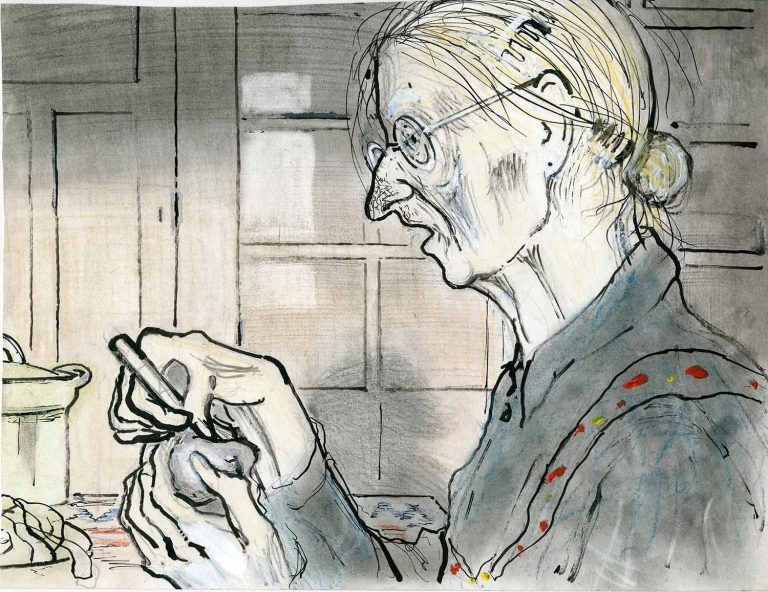

Miss Gerritsen came to us one morning a week as a ‘cleaning lady’. She could complain and lament as none other. Again and again. My parents couldn’t resist, so every time she managed to go home with a little something.

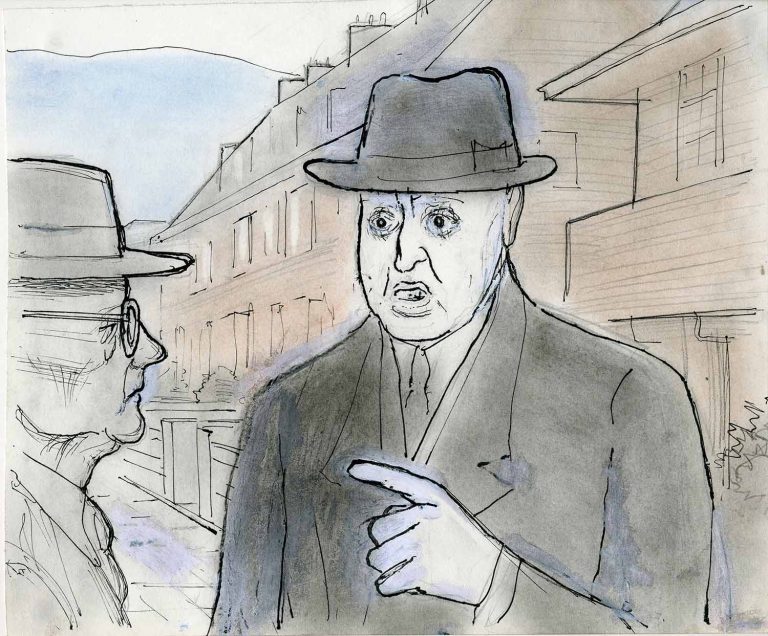

November. There was a rumour that the Grüne Polizei6 was preparing raids to force young men to work in Germany. Doctor Kramer from across the street assured his neighbour that he would refuse and tell the ‘gentlemen’: ‘ Is it true, by golly , that you are child kidnappers after all! ’

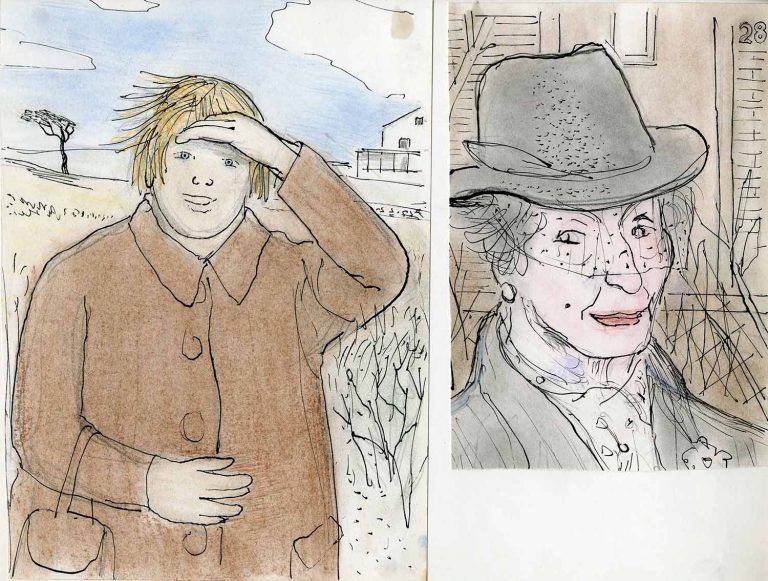

Some pro-German people lived on our road. Next to treason, however, the main danger was naiveté. Take, for instance, our maid. She had no notion of friend or foe. Luckily she was stuck in Friesland7 because of the railway strike. Our next-door neighbour was trustworthy, but she talked too much and couldn’t control her mouth.

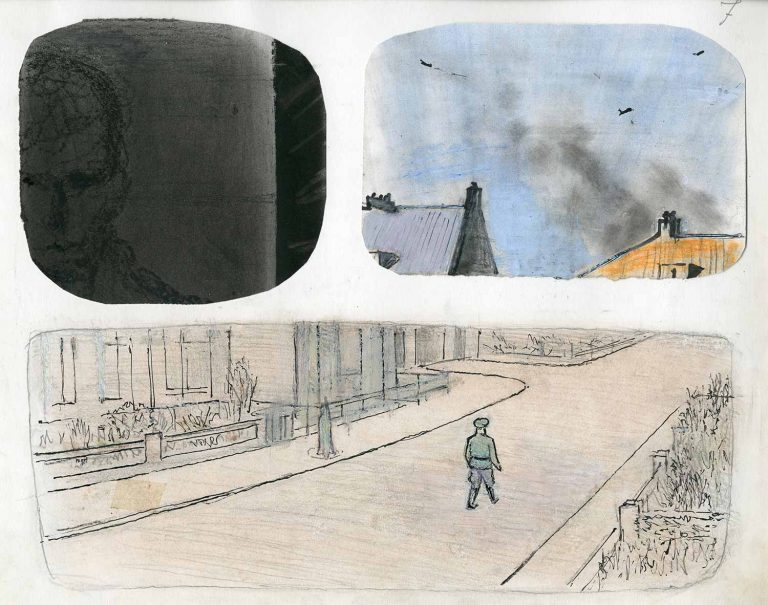

A few days later. A sunny lane, but also an eerily quiet lane. Just some sparrows. No one was allowed on the street, and the block was sealed off. A raid! With the two of us boys in a small den of one square metre, it was too frustrating. I wanted to just hand myself over. But that was no solution.

The ‘Tommies’ flew over about five times. Nosedives, bombs . . . and then they were gone. The V-2 launch pads were hit, but a few days later the first rocket shot into the sky again. It was very creepy when the roaring of the thing faltered all of a sudden.The yield of the raid was limited; it wasn’t such a thorough round-up after all.

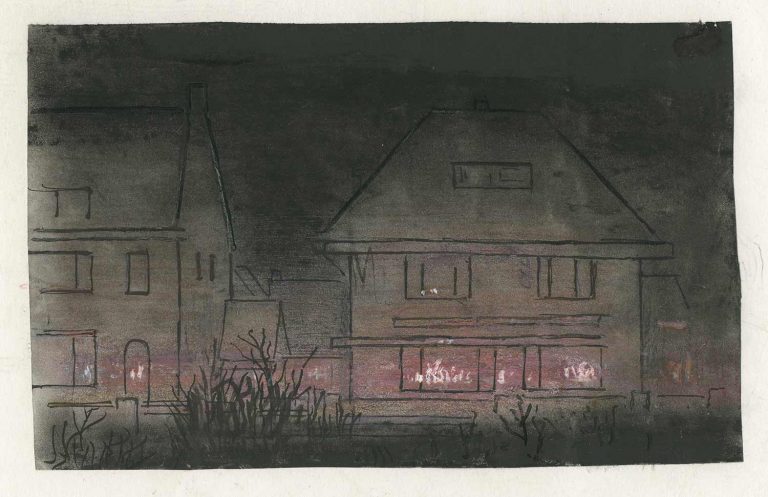

When people were queuing outside a shop, you knew that a ration coupon had been issued. But it was always ‘until stocks are exhausted’. And winter didn’t make things easier. It was bitterly cold. Many people wore wooden sandals, and some had swollen legs. Hunger oedema! A new concept for western Holland. Miss Kruythof of the Westerloo Quay died of hunger. She was buried in a bag, because wood was too costly a fuel.

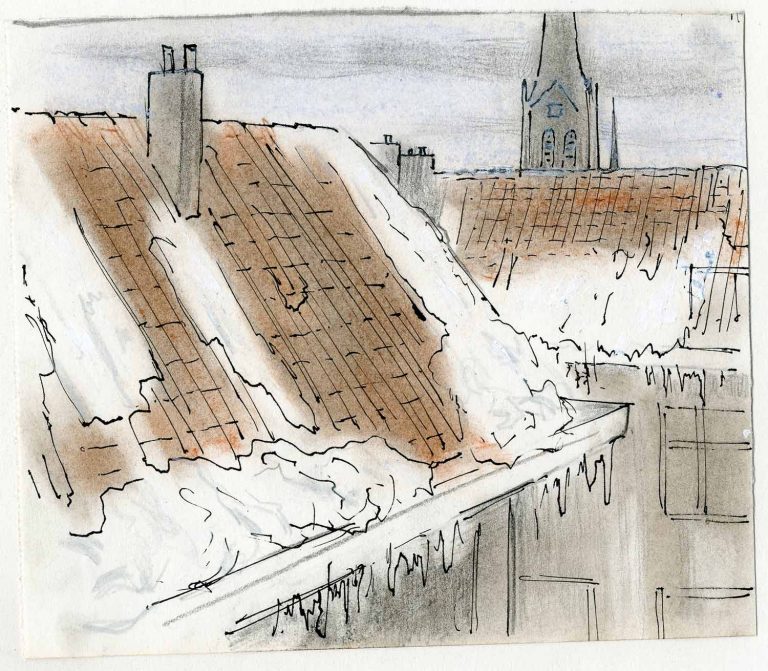

Thank God, thaw! The piles of snow thundered like avalanches from the roofs. It was 1 February, on the button.

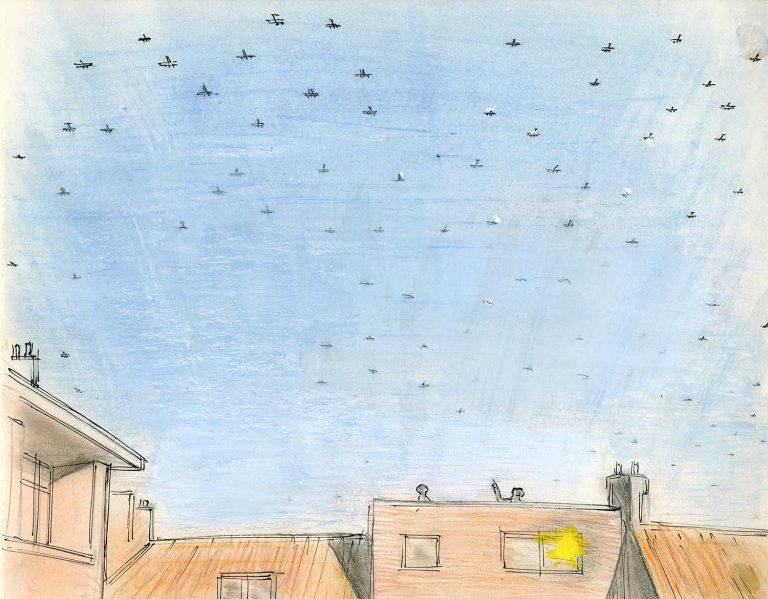

A Saturday afternoon, a few weeks later. A few signs of early spring, but the sky was filled with an awesome roar. Some mentioned Cologne, others Aachen – whatever! ‘Bomb the hell out of them, boys!’ you heard people shouting from their backyards.

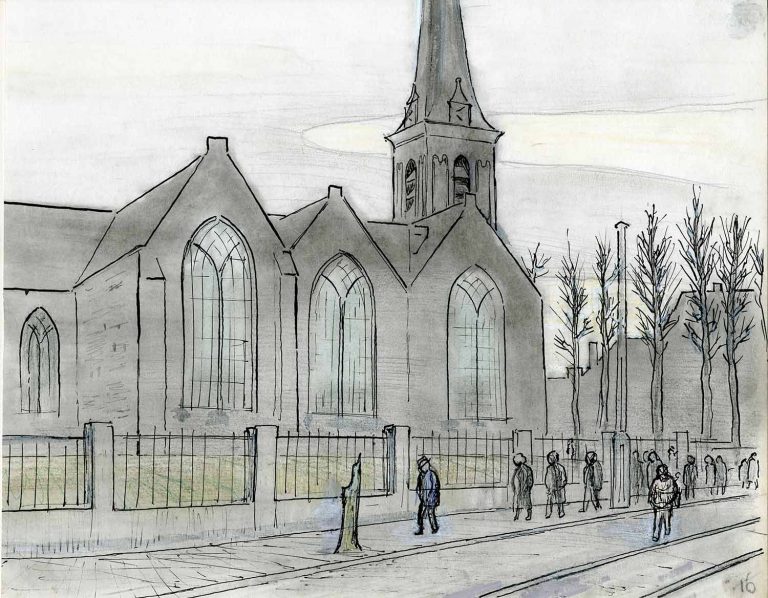

Nevertheless, some people around me were consumed by a completely different conflict. People from the Dutch Reformed Church! There was an internal conflict, and a schism came to pass. Fierce brochures were exchanged. It had something to do with baptism, I believe.

Saturday morning, 3 March. We were quietly enjoying our lean slice of bread. Then all of a sudden it was like the end of the world: a number of sledgehammer blows hit the earth. What? Where? It was as if it was inexhaustible, again and again. After a minute everything fell silent. An unreal silence.

We were still there and the walls were still standing. During the previous bombardments I had swiftly gone up to the attic window to orientate myself. Not now. There had been no sounds of planes, no howling of sirens. ‘It’s The Hague!’ someone shouted from a balcony.

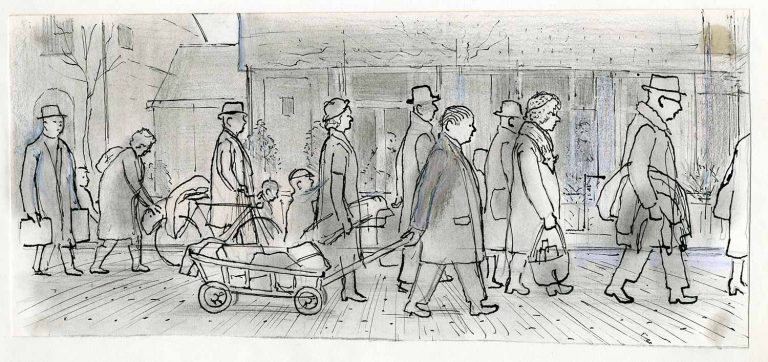

One hour later the first refugees from the Bezuidenhout8 quarter went through our lane. A procession of well-to-do people who had lost everything. You heard nothing but a slow shuffle. A lady rang our doorbell. Could she please use the toilet? Then she started crying.

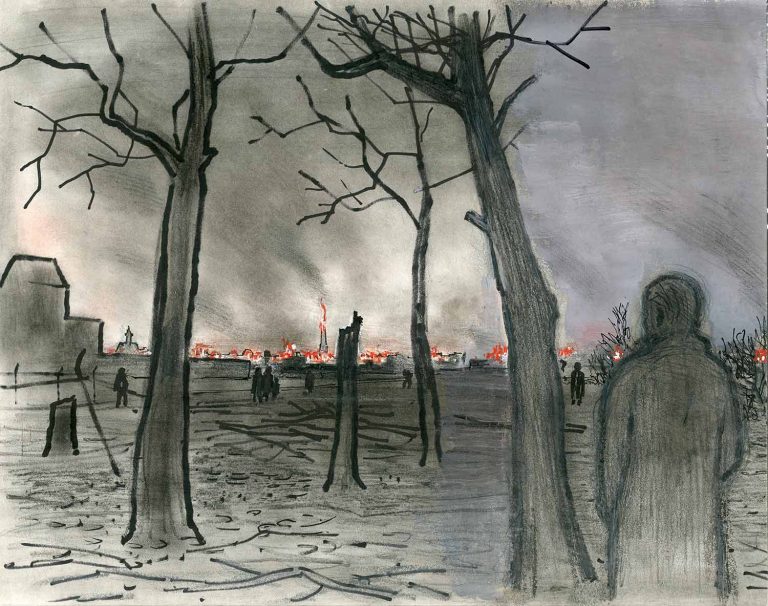

I don’t know whether the curfew had begun or not when I was standing in the farmers’ woods. The tall, slender bell tower of the Roman Catholic church on Bezuidenhout Road resembled a glorious torch and the buildings were glowing like coals in a cosy fireplace. ‘Resembled’, because this time the fuel was different.

For the residents of Westerloo Quay, with a view of The Hague, there was no need to light their candles or carbide lamps that evening. There was enough light!

It was a mistake. The pilots should have targeted the Benoordenhout, not the Bezuidenhout! That was where those awful V-2s were stationed. ‘How can we win the war with guys like that!’ doctor Bergsma sighed. He was often critical.

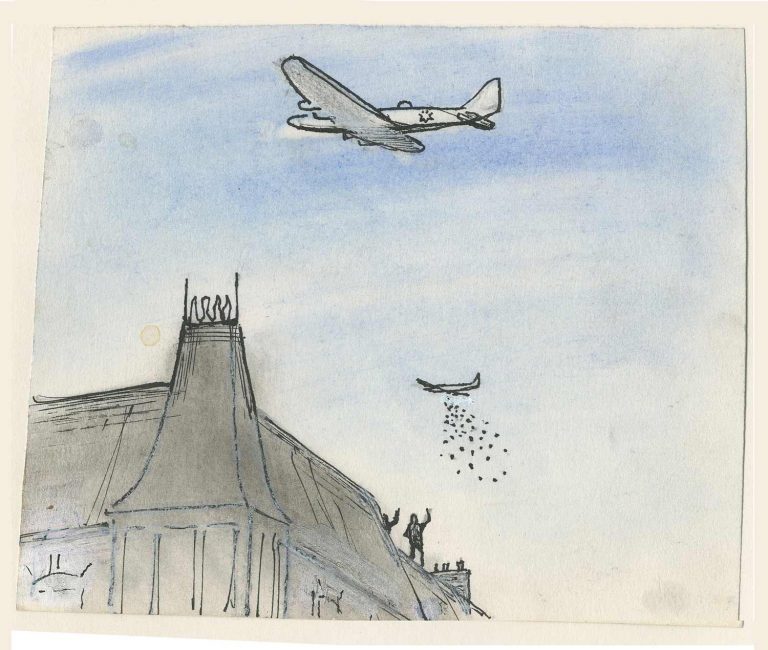

By permission of the Germans! After much argy-bargy, the Allied planes got permission to implement ‘food drops’ over the parts of Holland where there was starvation. In spite of everything it was encouraging.

Actually, it was an odd sight. It looked as though they were sprinkling crumbs.

Every now and then we got Swedish bread. Delicious! They cared about us! But still! In April the prospect became very dark, not to say frightening. In the area of the dunes, the so-called Fortress Holland9, a significant division of the Waffen SS10 had pulled together. They preferred to fight till death instead of surrendering. All reclaimed coastal land in the vicinity was now under water. With this knowledge we went to a prayer service in the old church. The only light at the end of the tunnel that the preacher could point out to us was the gate of heaven.

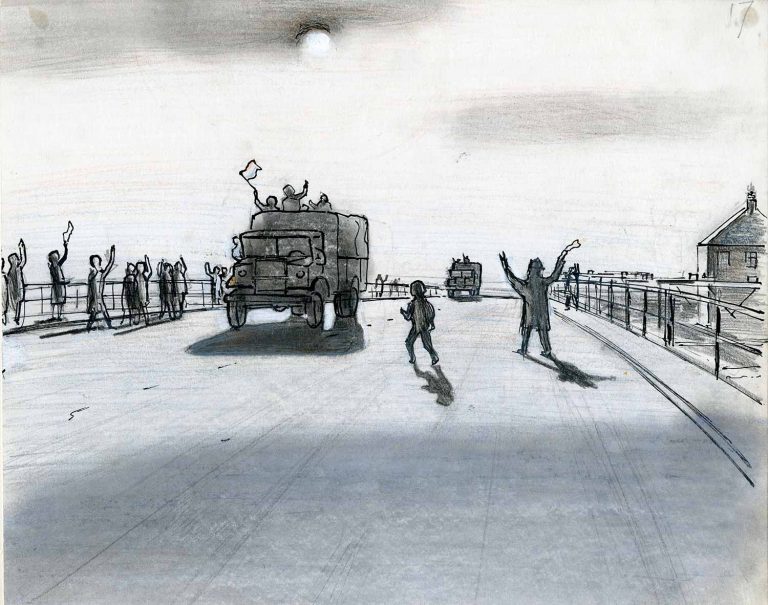

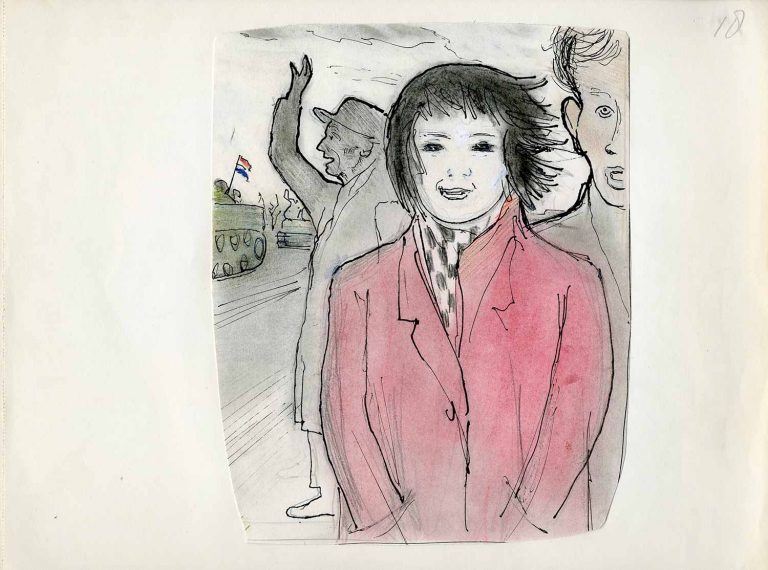

No one anticipated a miracle anymore, but slowly, slowly it took shape. Germany surrendered! Hooray, wonderful! But what will these SS men in the dunes do? Another day of tension. Well, the SS men did nothing! The arrival of the Allied forces wasn’t spectacular at all. Now and then they came rolling into our village with trucks or ‘carriers’ from the main road. The liberators seemed a little tired of all that victory business. But the welcome of the Voorburgers was heart-warming and one never got tired of that.

While I was standing at the side of the road, I all of a sudden spotted ‘her’. During the whole of the hungerwinter I hadn’t seen her, but I had dreamed about her often, quietly, at night in my bed. And now she stood there . . . along that road . . . with an unknown fellow!! I didn’t like the cheering and jumping to begin with, but now the fun was definitely over. My girl gone, my dream gone. I felt down and gloomy. I couldn’t stand the flags anymore, nor could I bear to hear ‘Oranje boven’11 again.

1All across the Netherlands people had the same feeling. It resulted in ‘Dolle Dinsdag’ (‘Mad Tuesday’, 5 September 1944).

2Betuwe is a region in central Holland.

3Known as Operation Market Garden.

4‘Only for the German army’.

5The local commander.

6The Green Police were responsible for internal order in the occupied territories.

7A northern province in the Netherlands, far away from Voorburg.

8The target of this Allied bombing were the repair wharfs and the depots of the V-2 rockets. They were situated in Benoordenhout (North Park) in The Hague. By mistake, the adjacent residential area of Bezuidenhout (South Park, closer to Voorburg) was bombed instead. Five hundred and fifty people died and many were wounded.

9Fortress Holland was part of the Atlantic Wall, a line of bunkers along the coast, stretching from Holland through Belgium and France.

10The combat units of the SS, later a regular part of the German Army.

11‘Orange up’ or ‘Orange on top’. Orange is the colour of the Dutch royal house. ‘Oranje boven’ is a royalist and patriotic slogan.