It’s winter in Brooklyn and it’s been snowing for days. The trains are fucked, the pipes are frozen, the heat is too strong, a mountain made entirely of snow that formed in Central Park five minutes ago just fell on a small toddler, the cops are shooting children in the street, all the vegetables look sad, it is not exactly Christmas, the President cut unemployment down to a month, the news says the Attorney General’s about to shoot someone on live TV, and tonight Sam and Eleanor are going to get dinner with Johnny and Jane. Won’t that be nice?

Right now, a train’s hurtling through darkness and out onto a bridge. Sam’s phone shouts I LOVE YOU in his pocket! Sam descends once more into darkness, and then, later, into the light! We all contain the miraculous inside of us! It is really something!

Sam went into the city for a meeting and during the meeting there were so many office buildings, the city was just lousy with office buildings today, of all days, and all of their windows kept reflecting the sun back and forth into Sam’s eyes, forever. In the middle of the meeting the managing editor, without saying a word, rose to her feet. She walked over to her desk and set her computer on fire. Everyone sort of lost track of her after that. And anyway there was still about two hours’ worth of meeting left. Sam, though a freelancer!, was important enough to have to come to the meeting and stand in the corner, shifting his weight from one foot to the other. Sam was blinking, and hungry, and there wasn’t lunch, and there wasn’t water, and there wasn’t any coffee, and then it was over, and when he got home, Sam would learn that he was not going to be paid for attending the meeting, and also there would not be any work for him this month, but they were so very grateful that he was such a team player and made the trip up! Meanwhile the police shot someone outside, the copy chief was weeping, and so were the sprinklers. Because of the computer that was set on fire. Things had, on the whole, once, been better than they were right now. Pretty much everyone could agree on this.

While Sam was in his meeting Eleanor sat at her desk in her open plan office while her boss sat her desk in her private office, thinking up the most beautiful, nested paywalls the internet had ever seen. Their subtlety would be magnificent, Eleanor’s boss thought. It was entirely possible no one would ever even figure out the way the paywall worked. The whole world could change. People could only see what they could afford to see. Eleanor’s boss could barely contain herself. She strode out of the office with a great and magnificent purpose. Eleanor watched her go. Johnny was inside a vast and endless chasm. At the other end was a sound that would change someone’s life. It could be said that museums were a sort of refuge, but I am not going to be the person saying that when you think about what it was that they bought all that art with. Jane was in a team meeting that wasn’t a team meeting so much as it was a private meeting, and it wasn’t a private meeting so much as it was an empty conference room with the lights off, and the room utterly empty, aside from the partner who called the meeting, who was beckoning for Jane to sit down, and there was only one chair, and he was in it. Jane was trying to do the math on where they could have put all the chairs so quickly and with such efficiency. She realized there were probably hidden closets in the room. This unnerved her. Outside was the city. It was absolutely full of people.

Off in the distance, the landlords laughed and laughed and laughed and laughed!

Sam left the city at three. THE TRAINS, THEY ARE SO FUCKED said the radio YOU CANNOT BELIEVE HOW LUCKY YOU WERE THAT IT ONLY TOOK YOU TWO HOURS TO GET HOME. SOON said the radio NOT NOW, BUT SOON, IT WILL TAKE DAYS FOR TRAINS TO CROSS THE RIVERS. YOU’D BE BETTER OFF ON HORSEBACK said the radio YOU’D BE BETTER OFF AS A BIRD. YOUR WHOLE LIFE COULD BE SO DIFFERENT, YOU COWARDS.

Eleanor texted Sam to say that she was on the train, but it was not moving. Meanwhile, the apartment was so very hot. Sam opened a window. He sat down at the table. He leaned back. He closed his eyes. Eleanor was still on the train where she was still reading that book about all the ways the world has ended and will end again someday. Once upon a time the trees had to bleed acid into the bedrock to turn it into soil, into something like a home. It’s weird to think about burning down the land to live in it until you think about America. Johnny picked up Jane from work on his motorcycle whose tires were made out of snow.

Meanwhile, as people made it home, the windows all around the block lit up, in minor ways, the too-sudden dusk.

Sam was standing outside the Italian place that used to be a Senegalese place a few blocks over. He and Eleanor were meeting Jane and Johnny for dinner soon. It was nine pm. The snow was still falling. The wind screamed for a bit and things got terrifying. Mountains of snow taller than cars and people were falling, and then the car alarms were screaming, and people were shouting for the cars to stop, but nobody could hear them over the cars, or the wind. Sam wished Eleanor was here, and then she was. Earlier today Eleanor had pricked her finger and written Sam’s name on her desk, where she earned all their money.

Dinner was delicious. Sam had an oxtail ravioli in a marrow sauce with a little fried sage, Eleanor had linguine with burnt vanilla beans and lobster, Johnny had this duck ragu with these thick ridged noodles that were definitely not spaghetti but I don’t know how else to describe them, and Jane had the single greatest vegetarian lasagna of her life. They had this wild orange wine Jane kept getting more bottles of while Sam stared at a point in the distance. Eleanor put her hand over his, and he turned to face her, and she was smiling. Everyone had been talking about their days but I already told you about them and I didn’t think you needed to sit through it all again. Then Sam and Eleanor started talking about this movie they’d seen, the one where it’s all sunsets and horses, where love is the sort of thing you could choke on. At one part, the happy couple is riding along, and then there’s just this sea of horses. They’re everywhere. The camera keeps pulling back and back and back, and it’s just horses, flooding the screen, forever. The sound is deadening. You know the lovers are saying something sacred to each other. You can almost hear it. After that everyone sort of sat there for a minute. Last night Johnny watched a documentary called One Day All Your Cities Will Be Salt. It was about how one day, all our cities will be salt. The angels will never come. Nothing we’ve ever done will last, not even our bones. The dead we’ve piled like so many trophies to record our glory meant nothing. Salt. That’s it. Jane quietly pays the check after going to the bathroom. The lights go out, and so does everyone else.

On the way home Eleanor put her head on Sam’s shoulder, and leaned in close like he could save her whole life. Sam leaned in and kissed her on her head, which was covered in a hat under a hood under the pile of snow that had gathered during the three-block walk, and then, dear reader, they were home, and out of their coats, at which point it turned out that Sam had to dig them a path through the living room to the bedroom, because, it turned out, the living room was full of snow!, because, it turned out, earlier it was hot and someone, it is a real mystery who it could have been, had opened a window, and the snow did fall and fall and fall through the window into the living room and now here we are, trying to get to bed. Inside the apartment, the snow was gone and the couch was a miracle. Outside, the wind was howling, and everything had turned to ice. In their warm dry bed Sam told Eleanor a story about the two of them except that all of his parts were played by the fallow fields in winter and all of her parts were played by the workers of the world, united. That’s just how it was: bombs burst like a song, and all the dreams you ever had just walked into the sea, and the workers of the world, united made love to the fallow fields in winter so tenderly that the world ended.

I don’t know how else to put it.

Sometimes it’s just so hard to sit down across from someone with all of their feelings all over their face and then you have to eat dinner like that with your feelings like that and you have a little drink like that with your feelings like that and then there you are, drunk, with your feelings, and with the check still to come and you think maybe hey do I have enough for this in checking right now?, and you look at your phone for answers, like as though anything in the world would have an answer. The dinner date was invented so long ago we don’t even have a year for it. What happened was one person asked another person if they wanted to get dinner, and the other person said yes. Nobody tells this story because nobody dies and there aren’t any explosions. I think there has to be a better way to tell it, where we can all just appreciate things a little more. There has to be.

Right?

Johnny and Jane went home alone because nobody knew they’d broken up. One day they just woke up and felt like strangers living inside a life they’d built together, and it was scary. It was scary to look into the eyes of the person whose health insurance you were on every morning and have her look at you like a stranger. It was fucking scary to come home every day to the man who built your table your bed your couch your home, who’d scaffolded up your sense of self for five years and have him tell you he hadn’t even the inkling of a notion of how to start to talk to you now. So Jane called a cab and Johnny rode a bus to a train and read an article on his phone about the tidal wave that would, one day, destroy the entire west coast. The tidal wave, Johnny read, wouldn’t look like a painting; it’d be a sea of cars and buildings rising up and folding in on itself, forever. Johnny texted Jane A sea of cars and buildings rising up and folding in on itself, forever and she texted him back An infinite void in the shape of the idea of California and he smiled, and looked out the bus. Outside the bus was an army on horseback, all bugles and bayonets, their coats all rotten with blood, all sagging in the snow and the dirty rain falling from the clouds that hung over all our heads that fateful night, and then they hooked a right on Union down towards the river, Jane texted Just saw a cannon being pulled down Flatbush, drifting west and Johnny texted her back a flood of horses and Jane texted back I can’t keep doing this. I just can’t. Jane’s phone was a sea of horses, it was a flood of horses, until all her phone could see was horses, until all she could see was horses, until the cab was full of horses, and her whole world was a sea of stampeding horses, stampeding her off to her apartment, to bed, and then there they were, a room full of horses, and it’s two it’s three its four it’s five it’s six in the morning, and nobody has made coffee, and she’s all alone, except for her whole entire apartment full of horses she’s going to have to walk through if she ever wants to get anywhere again, the horses, who are running over the bridge and the snow and your dreams and the landlords, they are coming, the horses, for you, and downstairs outside some asshole teenagers are waiting for a bus and pelting this ball against the dying metal sign that says BUS over and over and over and over and over again and, I swear to God, it sounds like victory, like there’s blood in the air, and the sun would just burn your eyes out if only you’d let it.

Image © istolethetv

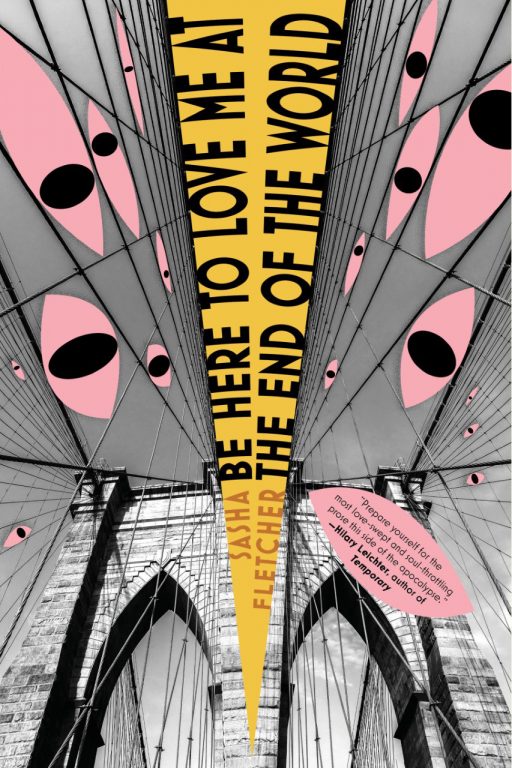

This is an excerpt from Be Here to Love Me at the End of the World by Sasha Fletcher.