In the 1980s I spent close to two years in the Peruvian Amazon living with Ashaninca people. My goal was to conduct an anthropological study of how indigenous Amazonian people used the rainforest. At first I paid little attention to what my Ashaninca hosts thought of me, because I had come to study them, and not the other way around. But I soon noticed that they too had an eye on me.

Most of the young people in the community in which I was living spoke Spanish on top of their indigenous mother tongue, and this allowed us to communicate freely. One day several adolescents and young adults were asking me questions about where I came from, ‘What’s it like in your land?’ and ‘Where is your land?’ In response, I spoke of a round planet on which we all lived. This led to some puzzled looks, so I began telling them what I knew about the movement of planets. Improvising with a lemon and a grapefruit, I mimed the rotation of the Earth around the Sun. Then I indicated to a point on the lemon, saying, ‘This is Switzerland, where I live,’ and to another point on the other side of the lemon to situate the Peruvian Amazon, saying, ‘And we are here.’ The young people listened to this demonstration in silence. When I was finished, they continued staring at me without saying anything.

Over the following months, I came to understand that the Ashaninca community had a different point of view on the matter. For them, the place I came from was not situated on the other side of a sphere on which we all lived, much less on the other side of a lemon. My world was situated below theirs. In their view, white people (virakocha in Ashaninca, gringo in Spanish) lived in an underground world – hence our pale skins – and accessed the Ashaninca’s territory by passing through lakes. We lived in towns filled with sophisticated technologies, and we occasionally came up to the Ashaninca’s world to capture their women and children and extract the fat from their bodies, which we turned into a fine oil that we used to run our machines and the motors of our airplanes.

I came to realize that many of the Ashaninca people I was living with considered me as a potential pishtako – or ‘white vampire’, who kills to extract human fat. I found it disturbing to think that people could see me this way. But over the months I began to think that the pishtako concept was in fact an appropriate metaphor for the historical behaviour of Westerners in the Amazon, who have long acted as a sort of vampire, extracting natural and human resources. In the sixteenth century, the first conquistadors destroyed and killed so they could return home with gold. Since then, the pattern has remained the same – Westerners have come to extract rubber, oil, wood and minerals, often at the cost of human life.

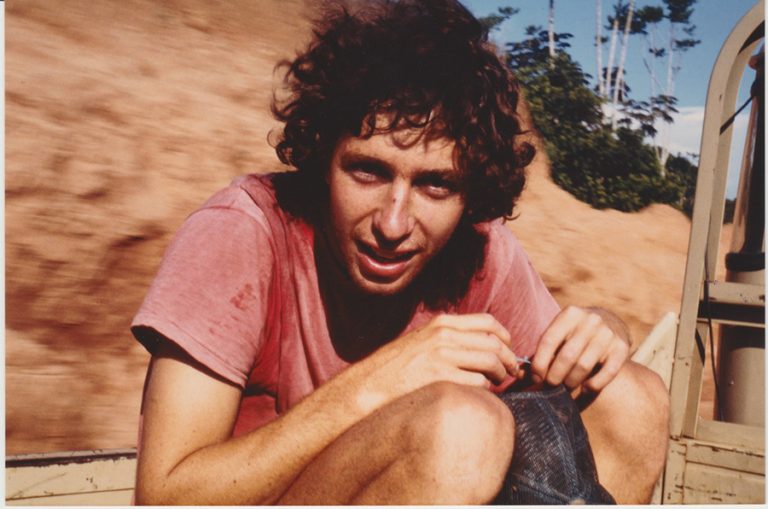

From the Ashaninca point of view, I was undeniably a gringo: white. But beyond the colour of my skin, I also had blue eyes, fair hair and a beard. And it so happened that these characteristics were exactly those used to describe pishtakos at the time. As far as my Ashaninca hosts were concerned, I certainly looked like a pishtako. So it seemed reasonable to think that I had come to extract something.

Several times during my stay in the community, different men took me aside and confided that they knew of nearby gold deposits that they would be willing to show me. They said this as if to test my interest. I would reply with indifference to these propositions, much to my interlocutors’ surprise. A gringo uninterested in gold? Was it possible?

People would regularly ask me questions about the world of gringos. One question in particular kept cropping up: why is it that gringos never have enough wealth? You can give them gold, they’ll only want more. Why? For the Ashaninca, gringos seemed obsessed by the accumulation of matter, objects and technology. From an Amazonian perspective, material accumulation had never been very practical, given the heat and humidity of the environment. It seemed unnatural.

My Ashaninca companions were still fascinated by the objects I owned, and tirelessly asked questions about them: how did I make rubber boots with leather linings? A Swiss Army knife? A portable tape recorder? I may have been a pishtako, but I owned fascinating merchandise nonetheless.

This fascination with the equipment of white people extends across various indigenous Amazonian groups. For example, the Piro people’s word for white people means ‘owners of objects’. The Yanomami call them ‘people of the merchandise’. Davi Kopenawa, a Yanomami shaman says this of the white people he’s encountered:

‘Their thought remains constantly attached to their merchandise. They make it relentlessly and always desire new goods. But they are probably not as intelligent as they think. I fear that this euphoria of merchandise will have no end and that they will entangle themselves with it to the point of chaos.’

As a student living with the Ashaninca, I became accustomed to being seen as a pishtako, obsessed with extraction and self-enrichment. But I also resolved to try to prove them wrong, to extract nothing, and to try to be useful to them.

After living with the Ashaninca people for twenty-one months, I wrote my doctoral thesis and began working for a humanitarian organization active in the Peruvian Amazon. Over the last thirty years, I have had the opportunity to travel around the region and meet people from numerous different cultures: Shawi, Awajún, Kukama-Kukamiria, Matsigenka and many others. I was surprised to find that all these people refer to pishtakos.

In 2002, while I was travelling with the Awajún people in the north of the Peruvian Amazon, we made a stop at an isolated house that belonged to a member of our party. The fellow’s wife welcomed us in, but when she saw me, she went pale and started shaking, because she thought I was a pishtako. Her fear was so intense that she could not bring herself to approach close enough to me to give me a manioc beer, which she was serving to all the other travellers in accordance with the principles of Awajún hospitality. Her husband reprimanded her and told her not to be afraid, and to serve me a beer like she had to everyone else. He worked as a bilingual teacher, and we had known each other for some time. When we had resumed our trek, he told me that his wife was not used to seeing white people, and that her fear was not ill will.

It was then that I realized that hosting a gringo–pishtako was like receiving a visit from Count Dracula himself, with his white skin and blood-tinged teeth. I was a grim prospect.

I made an effort to consider the following question: was I truly a pishtako? A white vampire here in the Amazon to extract human fat? I was certainly a child of capitalism, materialism and rationalism. My ancestors had participated in the development of global capitalism, the wheels of which had been greased by the ruthless exploitation of indigenous Amazonian people. What I’ve read of the atrocities committed against indigenous Amazonian people during the rubber boom of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was certainly gruesome. It was true that my culture was pishtako-like, and therefore so was I, at least to a certain extent. The pishtako image became all the more disturbing because it was coherent.

As an anthropologist, I had extracted data from the Ashaninca while I was living with them, which I then turned into a doctoral dissertation for my personal benefit. And now, as I worked for a humanitarian organization that backed indigenous initiatives like land titling and bilingual education programmes, I felt relieved that I could partly atone for my past. Reciprocity, I realized, is an antidote to pishtako-hood. But I did not discourage Amazonians from seeing Westerners as pishtakos, because I had come to view the metaphor as essentially true.

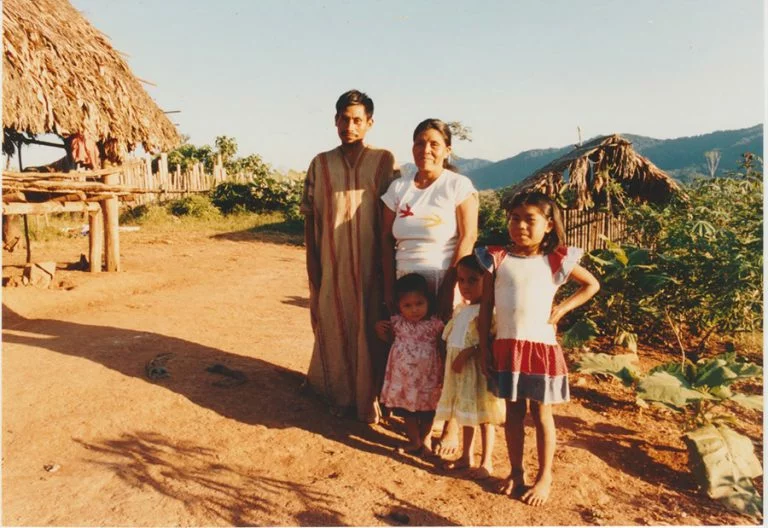

Jeremy Narby on the back of a pick-up truck, after six months living in the rainforest with Ashaninca people, Pichis Valley, 1985 / Courtesy of Jon Christensen

Anthropologists who have studied pishtako stories consider them part of a tradition dating back to the first contact with Europeans towards the end of the sixteenth century. These stories have long been told by native peoples in Peru, both in the Andes and the Amazon. For Peruvian anthropologists Fernando Santos-Granero and Frederica Barclay, pishtako stories reflect ‘a fear of white people and their predatory powers’. But they note that these stories have evolved over time. Those circulating in the Peruvian Amazon in the 1980s, which I heard with my own ears, responded to the aggressive government policy of colonization and deforestation. In 2010, a new kind of pishtako story was circulating through the region: the white vampires had gone from individuals extracting fat to flying gringos equipped with metal wings who killed young people to extract their eyes, hearts and other organs, which they would send on to the United States, where they could be used to make transplants for the elderly. These contemporary pishtakos no longer emerged from lakes, but from the sky. When they moved, they emitted multicolored lights, and they always carried a small freezer where they stored the different organs extracted from their victims.

But there is also a new type of extractor which has emerged over the last twenty years – a new generation of white people who have descended on the Amazon in search of shamanic experiences and healing. That white people should be in search of healing does not surprise anyone. From the Amazonian perspective, it makes sense that the children of pishtakos, whose lives are saturated with objects, technology and materialism, should seek healing and meaning from Amazonian healers.

What is different this time around is that the white people say they want to learn from Amazonians. They are not coming to extract gold or body parts, but to learn. And they are even willing to pay for this knowledge. All this is new.

What, then, do indigenous Amazonians think of the Europeans and North Americans who come to the Amazon to drink ayahuasca? I put this question to Amazonian people working to defend Amazonian knowledge and culture, but who have no direct interest in the ayahuasca economy, or in the commerce of medicinal plants.

Never Tuesta Cerrón, the Awajún director of a training program for indigenous bilingual and intercultural teachers, told me he felt optimistic about the new visitors.

‘I think it is good that the Europeans get to know the knowledge of indigenous peoples.’ He was pragmatic and open: gringos should feel welcome to learn about their knowledge, all they asked is that Westerners respect the proper procedures.

But he also insisted that this was merely his personal opinion, which he viewed as insufficient to address my query. On his own initiative, he submitted the question to several indigenous elders who work for the programme he runs, and who had been elected by their people to teach their language and culture to young indigenous teachers in training.

The elders who responded insisted that there was a connection between, on the one hand, the plant and the land; and on the other, the plant and the people of the land, who know how to use it. One of the specialists even wondered whether ayahuasca would have the same effect if drunk (or grown) in other lands. Ayahuasca is profoundly embedded in their space and culture, and it was unclear to some of them whether white people – who may or may not live in an underground world, with different rules and practices – would be able to use ayahuasca in the same way. What ayahuasca is in one world, they say, may not be what it is in another.

The elders believe that white people who drink ayahuasca outside its natural environment contribute to ‘breaking its strength’ and ‘weakening the maestros’ – the maestros being the shamans who prepare and administer the brew. White people again are seen as extracting vitality from the land; yet another strand in the evolution of the pishtako stories.

‘They already stole everything we had’, as one of the specialists puts it, asking why Westerners must now take ayahuasca too. Another suspects that what white people really want is to identify and steal the ‘essence’ of ayahuasca, and with it the ‘spiritual force’ of indigenous peoples.

I think there is a deep truth in the pishtako concept. Most Westerners, even well-meaning ones, end up in vampire-like relationships with Amazonians. Most often this is due to the power imbalance between the two sides. The problem is that Westerners stand to extract considerably more value from the encounter than the locals.

My life was certainly changed by living with Ashaninca people, much more so than the other way around. And Western ayahuasca drinkers often claim that their time in the Amazon changed their lives. But what do the indigenous people who attend to them get out of it? Perhaps some small form of payment, but certainly nothing life-changing.

Undoing this imbalance, and making our relationship with Amazonian people more reciprocal, is the work of a lifetime.

The last three paragraphs of this article benefitted from an exchange with my friend and fellow recovering pishtako, Jeronimo Mazarrasa.