[transformation: Daphne]

Who roots, flares into leaf, becomes tree.

But in the change before the change

Zeus’s son courses her like a hound

and Daphne is a hare, trying to leap free.

That day at the races a whippet lost its head

in the hold, its cries leaking out of the dark trap

like poisoned milk. Then clank and all the gates

lifted, and the dogs streaked out, hurtling after

a dummy on castors, which rattled over the sleepers

of a long, greased rail. The pack was an unreadable blur.

Once it was over, handlers hooked their legs

over the barrier and came for their dogs,

clipping on each leash. Zeus behind the scenes:

his electric-shock collar, his snippets of meat.

Out beyond the pale there’s no straight course,

just waterlogged fields and Daphne’s hectic

blurts of speed. She’s at the edge of her wits,

retching with fear, and he is everywhere,

stumbling her up, ahead of her, above,

his stink, his spit; he hollers and barks

in the rough of his throat, cuffs out her legs

from under her, tears at her flanks with his teeth

but still delays, and still she doubles back

and jinks and feints and flees.

By nightfall she is ragged in her hind-end,

blood-ebbed and frayed and wanting to be gone

into the gentleness, though there’s this bright light,

this dazzle in her eyes, that won’t let her sleep.

She cries for her daddy like any other girl

who’s run beyond her strength, whose heart has failed.

When a hare dies it screams like a mortal child.

Disconcerted, Apollo looks up from the field.

There’s Zeus in the dark holding the lamp,

keeping it steady for the rape, and the kill.

*

MENINGITIS

My grandmother, diminished in her bones,

loyal to her large-print Mills & Boon

and her soaps, bent perpendicular over her zimmer,

weeping, still weeping for her daughter June,

who was sweet, so sweet, the child of her heart –

soft blonde curls and forget‑me‑not eyes,

gentle and kind – how June took care of the evacuees,

holding out their towels as they stepped

from the disinfectant bath to be deloused.

How, after all that – the World’s War

and its shell-shocked peace, the Mickey Mouse

gas mask packed away at last, June

went to bed with half a soluble aspirin

for a headache and by the morning was gone.

The way my grandmother tells it, she didn’t know

there was anything out of the ordinary wrong,

and June died in the night in wet sheets, alone,

as the terrible roses bloomed beneath her skin.

My grandmother out of her mind with pain,

writhing and kicking on the kitchen linoleum,

while my uncle as a boy watched on.

Which is why my father came to be born,

to bring her back to the living, a baby to hold.

And this is my inheritance, this heirloom of grief:

the way my daughters’ fevers crush me,

how I check their skin obsessively

for tell-tale burns, how I scoop them

out of the flames where the devil eats them,

daughter like a hot poultice I hold

against my frightened heart, the marks I make

above my door that the angel of the plague

might pass, where my grandmother waits,

standing on the threshold in her red velour slippers,

unable to step over, peering fearfully into the dark.

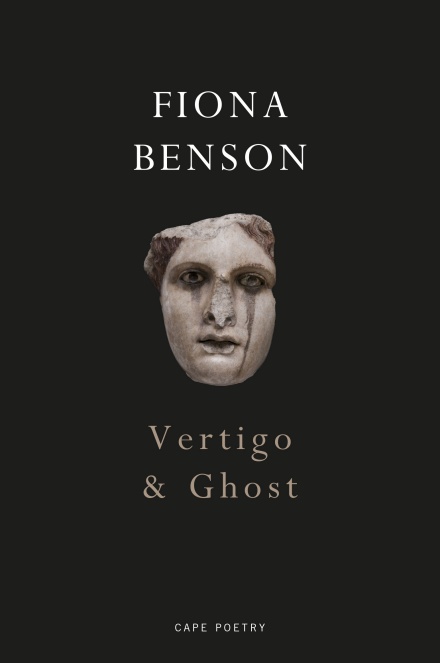

These poems appear in Vertigo & Ghost by Fiona Benson, published by Jonathan Cape, £10.00. Vertigo & Ghost has been shortlisted for the Rathbones Folio Prize 2020.