It wasn’t, it just couldn’t be. Isadora had a boyfriend, didn’t she? He was probably at that very moment sitting on the bleachers, waiting for her to come onto the field.

I’d always suspected the twins, Greice and Kelli, two stocky blondes with thighs wider than the entire breadth of my body. I don’t know. Maybe it had something to do with how they walked, with how thick their legs were, but Isadora wasn’t like that at all. Isadora came to practice with manicured nails. She had a Malhação notebook with Cláudio Heinrich on the cover, the height of heteronormativity. We were fourteen, fifteen years old and we all believed blindly in horoscope magazines. We were girls who did supposedly girl things. Was soccer a sign? I don’t think so, nearly all the girls had boyfriends, except for Greice and Kelli, and I didn’t have one because I was a puta, as they used to say, I hooked up with everybody.

The truth is I didn’t even like soccer. I liked handball – or ãndebóu where I’m from – but stopped playing because some asshole kept calling me a lesbian, claiming I rubbed up against her during matches. On my mother’s life, I was not a lesbian, and I wasn’t attracted to her, either; she was way too ugly for my nonlesbian tastes. But Ariela, now she was really something. She used to fly into the zone, ball in hand. I’d watch her movements in slow, near-ethereal motion: Ariela with her long legs, bending as if in a classical ballet sauté, muscles tightening before expanding, flying, breaching the zone, her arm rising, veins popping in her fists as she bit her lower lip, then released the grip in her hand. A cannonball. Ariela was left handed, which confused people. On account of the ogre who was always calling me a lezzo, I became a goalkeeper to ward off any awkwardness. I was a great goalkeeper, a brilliant one. Except every time Ariela rushed toward me, everything disappeared, and I froze in her gaze. Marco, our after-school coach, always got really ticked off. He always put me up against Ariela because I was the best goalkeeper and she was the best wingman. I lost count of the balls I took to the face, the belly, I lost count of the broken fingers – but it was all worth it. At the end of practice, she’d hug me and tell me good match, fair game. Then she’d run her hand through my hair, plant a crackling kiss on my cheek, and bump me with a really lame punch. It became a sort of ritual for me, and if this didn’t happen at the end of a match, it was neither good nor fair.

Oh, what I would’ve done to have arms like Ariela’s! But mine have always been smooth, unblemished, and hairless, with no veins. Ariela’s arms, meanwhile, were tan and dotted with freckles, her veins popped, and her knuckles were chunky from cracking them so often. My fingers are weird and all bent up these days from being broken so many times.

After the match, we’d sit on the bleachers with the boys. I was hooking up with Diogo at the time, a gangly German kid with a bowl cut. Ariela was hooking up with Felipe, a senior. We’d eat ice cream and then walk up to the park to watch the boys play basketball. My teenage years were chock full of sports and activities I wouldn’t even dream of doing today. I don’t know if the school encouraged us or if all the teens there just happened to like sports, but the fact is we always came out on top at the intramural tournament. We were hooked on games. I remember once cutting class with everyone to watch Grêmio and Ajax play the 1995 Intercontinental Cup. The gremistas suffered through the entire game, while the colorados spent the match rooting against every ball that entered the box. We lost in penalties. Four to three. The ogre who was always calling me a lezzie ratted on us to the guidance counselor, all because she hadn’t been invited. The next day, everyone was in the principal’s office, explaining themselves. Parents apologized to the principal and teachers and vowed it would never happen again.

The day after the event, Marco asked me if I wanted to play soccer. I said I’d rather watch soccer on TV, at home during class. He tried to feign annoyance, to act like he didn’t agree with what we’d done, but instead he laughed at my joke. I said yeah, I’d like to play soccer, so he sent me to tryouts at a soccer club in the city starting a women’s team. I showed up at the scheduled time and took the physical as well as an unbelievable written test on general and sports knowledge. The following day, he asked if I’d been selected as goalkeeper, and I said no. He pulled a saddish face, in solidarity, I think, and said maybe next time. Then I told him I’d gotten picked for offense. Jersey number nine. He looked at me, intrigued, and cracked a satisfied smile.

Isadora was number ten, Tui eight, and Rose eleven; Greice was five and Kelli was two, Simone was four and Jana was goalkeeper. I don’t remember the rest of them. That was my soccer team. We traveled together and struck up friendships with girls on other regional teams. We had games almost every weekend. We were awful, but it didn’t matter. It was cool to travel to a different city every Saturday and celebrate goals with pileups, hugs, or jumping around. There, I wasn’t ‘a gross lesbian who rubs up against people’ – there, I could touch people without fear of a stupid nickname.

A little while later, I bumped into some of the girls from the Parobé team at a gay party. Daphne Teco-Teco was shocked to see me. This was a long time after I’d stopped playing, about three or four years after, I think. She asked me what I was doing there and if I knew it was a gay party, and I said I knew, that was why I was there, so we laughed and she slapped me on the shoulder like she wanted an explanation. I just smiled and asked her to be patient, I didn’t really feel like telling my story then. She pulled me up onto a small stage and said she wanted to introduce me to someone, her girlfriend. She looked over at the dance floor, then toward the room’s darker corners, and pointed out a tall blonde leaning against the bar, her back to us. We jumped offstage holding hands. She dashed off, tugging me along, and introduced me to Sandra. I looked at Sandra, who nearly choked on her drink. She greeted me and said my name as she coughed with surprise. Sandra, the ogre who’d called me a lesbian at school. I laughed and said she should’ve paid closer attention to the hints she’d dropped me, and I swore I’d never, ever rubbed up against her in handball class. I wasn’t even aware back then of my feelings for Ariela. Another day, I found Ariela on social media. She was a lawyer, married, with kids. No way, I thought. I thought of a bunch of things that day, the paths our lives had taken, then looked up the other girls on our team whose full names I still remembered. Apparently, I’d changed the least out of all of them. Might just be my impression, though.

I went to Isadora’s profile and saw a bunch of photos of her and Kelli. They were married. So my eyes hadn’t been playing tricks on me back then. Their passion for each other had always been there. I thought of the day I’d gone back for my shin guard. The whole team was warming up on the field, kicking a ball around. Except for Kelli and Isadora. Walking into the locker room, I heard the shower running. There were slats at the bottom of the stall door, and through them I glimpsed four legs in a tangle, a pair with rounded ankles that surely led to Kelli’s thick thighs, and another pair with Isadora’s manicured toes.

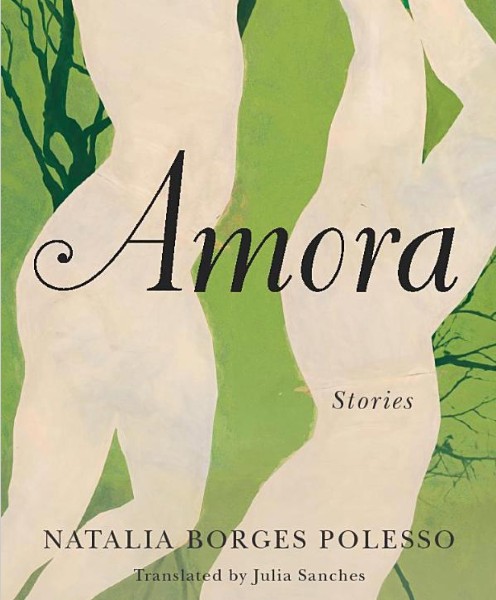

‘Thick Legs’ is included in Natalia Borges Polesso’s collection Amora, translated by Julia Sanches and published by Amazon Crossing.

Image © Rene de Paula Jr