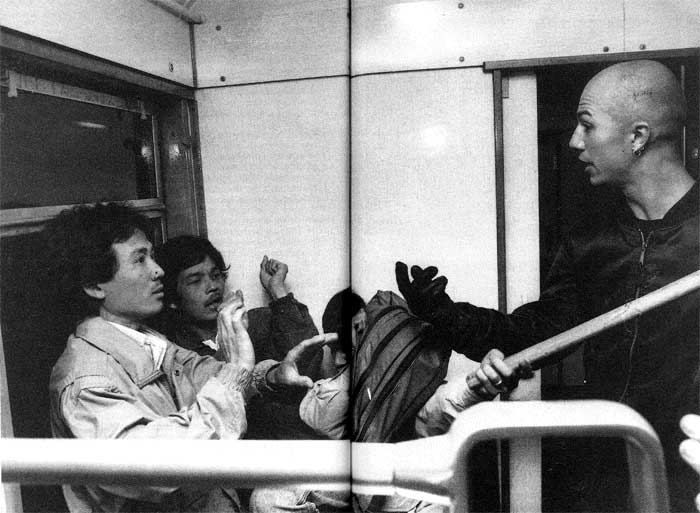

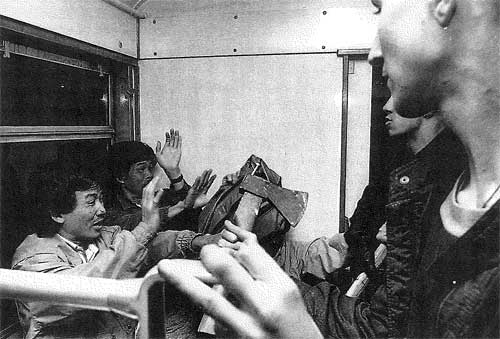

Two passengers in a railway compartment. They have commandeered the little tables, clothes-hooks and baggage-racks: made themselves at home. Newspapers, coats and handbags lie around on the empty seats. The door opens, and two new travellers enter. Their arrival is not welcomed. The original passengers, even if they do not know one another at all, behave with a remarkable degree of solidarity. There is a distinct reluctance to clear the free seats and let the newcomers share them. The compartment has become their territory to make available, and they regard each new person who comes in as an intruder. This behaviour cannot be rationally justified; it is more deeply rooted.

However, matters virtually never get to the point of open conflict. That is because the passengers are subject to a system of rules; their territorial instinct is curbed by the institutional code of the railroad as well as by other unwritten norms of behaviour: like that of courtesy. Looks are exchanged, and formulaic apologies are muttered through clenched teeth, but the new passengers are tolerated. One gets used to them. Yet they remain, even if to a decreasing degree, stigmatized.

This harmless model is not without its absurd features. The railway compartment is itself a transitory domicile, a location which serves only to change locations. The passenger is the negation of the sedentary person. He has traded a real territory for a virtual one. Despite this he defends his transient abode with sullen resentment.

Every migration, irrespective of its cause, nature and scale, leads to conflicts. Self-interest and xenophobia are anthropological constants: they are older than all known societies.

To avoid blood-baths and to make possible even a minimum of exchange between different clans, tribes and ethnic groups, ancient societies invented the rituals of hospitality. These provisions, however, do not abrogate the status of the stranger. Quite the reverse: they fix it. The guest is sacred, but he must not stay.

Two new passengers open the compartment door. From this instant, the status of those who entered earlier changes. Only a moment ago, they were the intruders; now they are natives. They belong to the clan of compartment-occupants and claim all the privileges due to them. The defence of such an ‘ancestral’ territory, that was only recently occupied, appears paradoxical; noteworthy is the absence of any empathy with the newcomers, who have to struggle against the same opposition, face the same difficult initiation, to which their predecessors were subjected. Curious, the rapidity with which one’s own origin is concealed and denied.

Clan and tribal groups have existed since the earth was inhabited by human beings; nations have existed for only 200 years or so. It is not difficult to see the difference. Ethnic groups come into being semi-spontaneously, ‘of their own accord’; nations are consciously created, and are often quite artificial entities, which cannot cohere without a specific ideology. This ideological foundation, together with its rituals and emblems (flags, anthems), originated in the nineteenth century. From Europe and North America, it has spread over the whole world.

A country that wants to succeed as a nation needs a well-coded self-consciousness, its own system of institutions (army, customs and excise, diplomatic corps) and numerous legal means of demarcating its boundaries (sovereignty, citizenship, passports). It is rarely managed without historical legends. If necessary, proof of a glorious past is forged, venerable traditions dreamed up. Usually the more artificial a nation’s genesis, the more precarious and hysterical its national feeling. That holds true for the ‘overdue nations’ of Europe – the new states which emerged from the colonial system – as well as for forced unions like the former USSR and Yugoslavia, which have a tendency towards disintegration and civil war.

Of course, no nation has an absolutely homogenous ethnic population. This fact is in fundamental conflict with the national feeling which has taken shape in most states. Consequently, as a rule, the leading national group finds it difficult to reconcile itself to the existence of minorities, and every wave of immigrants appears to be a political problem. The most important exceptions to this pattern are those modern states which owe their existence to migration on a large scale; above all the United States, Canada and Australia. Their founding myth is the tabula rasa. (Though that depends on the extermination of the indigenous population.)

For almost all nations the distinction between ‘our own’ people and ‘strangers’ appears quite natural, even if utterly questionable historically. Whoever wishes to hold on to the distinction needs to maintain, by his own logic, that he has always been there – a thesis which can all too easily be disproved. A national history assumes the ability to forget everything not in accord with it.

External and self-ascription can never be made to coincide. The meaning of the sentence ‘The Finns are cunning and drunken’ depends on whether a Finn or a Swede is speaking. Consider the different reactions it provokes: among Finns only a Finn would be allowed to say it; coming from a Swede it would cause a scandal. Such differences always conceal a long history of contact and conflict.

Contemporary migrations differ from earlier movements of people in more than one respect. First, mobility has increased enormously in the past two centuries. The developing world market has required global mobilization and imposed it by force where necessary, as with the opening of Japan and China in the nineteenth century. Capital tears down national barriers. It disregards patriotic and racist impulses, but can make tactical use of them if necessary. In general, though, the tendency is for the free movement of capital to draw labour behind it, without regard to race or nationality. With the globalization of the world market (which was completed only very recently), the new migratory movements will probably take the place of state-organized colonial wars and expeditions of conquest. Whereas electronic money follows only its own logic and playfully overcomes every resistance, human beings act as if they were subject to some incomprehensible compulsion. Their embarkations are like movements of flight, which it would be cynical to call voluntary.

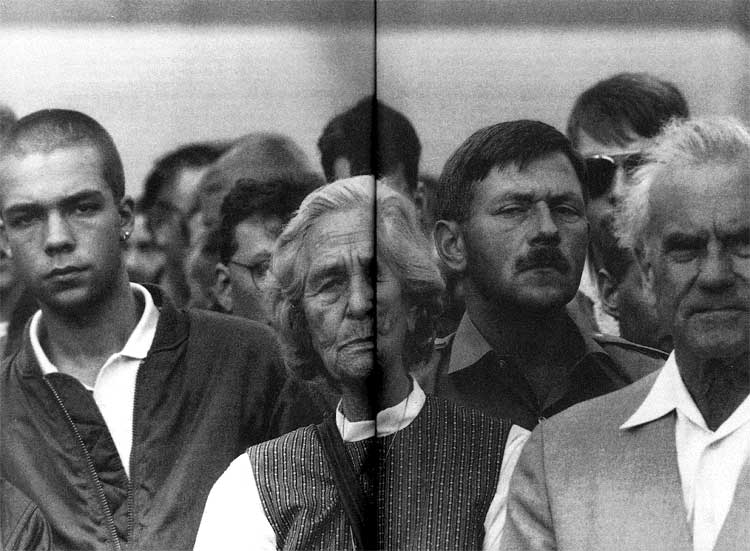

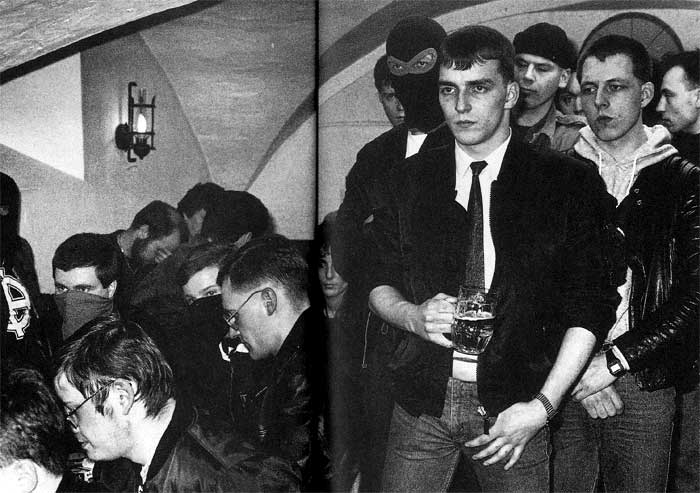

War veterans and young ‘comrades’ in Wursiedel, Bavaria, listen to a speech by neo-Nazi leader Michael Kuhnen.

No one emigrates without the promise of something better. In early times legend and rumour were the media of hope. The Promised Land, legendary Atlantis, El Dorado, the New World provided the magical stories that motivated many to set out. Today it is the high-frequency images which the global media system transmits to the very last village of the developing world. These images have less substance, less reality, than even the most marvellous ancient legends; however, their effects are incomparably more powerful. Advertising, which is effortlessly understood in its wealthy countries of origin as an empty sign without a real referent, counts in the Second and Third Worlds as a reliable description of a possible way of life. To a large extent it determines the horizon of expectations prompting migration.

For centuries the world’s population fluctuated regularly, but never increased significantly. However, since the world’s population has begun to grow exponentially, the rules of the game have changed. Sooner or later the unimaginable quantitative increase must have an effect on the quality of the migratory movements.

That this is already the case is doubtful. Today it is estimated that more than twenty million immigrants live in Western Europe. The flow of refugees in Africa and Asia is on a similar scale. These are large numbers. But if one considers that between 1810 and 1921 thirty-four million people, mainly from Europe, emigrated to the United States alone, then it is hardly possible to argue that these figures are unprecedented. Indeed, it could even be claimed that modern migration has, so far, been rather limited, especially if measured against the absolute increase in the world’s population (the United Nations forecasts estimates a growth of almost one billion for 1990-2000). This invites the conclusion that only a small fraction of the potential migrants has actually set itself in motion: the real migration of peoples is still to come.

The media approach this conclusion fatalistically and illustrate it with fantastic doom. A strange enjoyment of fear emerges from the apocalyptic pictures they project. All the present-day phenomena of crisis – the unstable condition of the world economy, the huge technological dangers, the disintegration of the Soviet empire, the ecological threat – provoke scenarios of this kind. Possibly the anticipatory panic even serves as immunization, a kind of psychic inoculation. At any rate it leads not to solutions but, at best, policies of stop-and-go, alternating between timid repair measures and obstacles to thought and action.

A life-boat is packed with shipwreck survivors. In the stormy sea around it there are other people in danger of going under. How should the occupants of the boat behave? Should they push away or hack off the hands of the next person who grabs the side of the boat? Or pull him on and let the boat sink? The dilemma is part of the standard repertoire of casuistry. The moral philosophers who discuss it usually pay no attention to the fact that they themselves are safely on dry land. Yet all abstract reflections founder on just this ‘as if’, no matter what their conclusion. The best intention is frustrated by the cosiness of the seminar room, because no one can credibly declare how he would behave in an emergency.

The parable of the life-boat is reminiscent of the railway compartment model. It is that model taken to its extreme. Here, also, travellers act as if they were property owners, with the difference that the ancestral territory they defend is a drifting nutshell and that it is no longer a matter of comfort but of life and death.

It is of course no accident that the image of the life-boat recurs in the political discourse about immigration, usually in the form of the assertion, ‘The boat is full.’ That this sentence is factually inaccurate is the least that can be said about it. A look around is enough to disprove it, as those who use it know. But they are not interested in its truthfulness; they like the fears it conjures up. Evidently many West Europeans believe that their lives are endangered. They compare their situation to that of shipwreck survivors. Suddenly those who have a roof over their heads imagine that they are boat people, emigrants sailing steerage, Albanians on an overcrowded ghost ship. The distress at sea which is hallucinated in this way is presumably intended to justify behaviour which is only conceivable in extreme situations. From here it is not a very big step to hacking off hands.

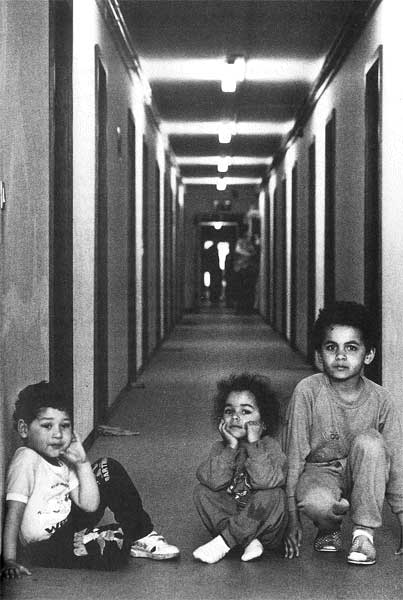

Russian Jewish children in a refugee hostel, Berlin.

There is something comforting about the railway compartment analogy, simply because the location of the action is so restricted. Even in the terrifying image of the life-boat individual human beings can still be recognized–as in Géricault’s painting ‘The Raft of the Medusa’, where eighteen individual faces, and their fates, can be distinguished. Contemporary statistics, whether they are referring to the starving, the unemployed or refugees, express everything in millions. These are numbers which paralyse the imagination. The aid organizations and their campaign managers know that these numbers are incomprehensible, which is why they always show only a single child with huge pathetic eyes, so as to make the catastrophe commensurable to our compassion. But the terror of the big number is without eyes. Empathy breaks down before such excessive demand, and reason is made aware of its impotence.

Superfluous, superfluous . . . an excellent word I’ve come up with. The deeper I plunge into myself and the closer I examine the whole of my past life, the more I am convinced of the harsh truth of that expression. Superfluous – precisely so. The word does not apply to other people . . . People are good and evil, intelligent and stupid, pleasant and unpleasant; but superfluous?

It would not have occurred to Ivan Turgenev’s hero Chulkaturin to regard his wet-nurse, the coachman, the peasants on the estate – still less whole villages, regions, peoples and continents – as superfluous; he talks rather of his father, a landowner, with his country houses, and of himself, with his boredom, his loneliness and his disgust – ‘The word does not apply to other people,’ he thinks.

One hundred and fifty years after his demise Chulkaturin’s situation seems altogether idyllic. Of course there have been great massacres and endemic poverty in every age. Enemies were enemies, and the poor were poor; yet only since history has become world history have whole peoples seen themselves condemned to superfluousness. The judges who pass this sentence go under the names of ‘colonialism’, ‘industrialization’, ‘final solution’, ‘Versailles’ or ‘Yalta’, and their decrees are pronounced openly and put into practice systematically, so that no one can be in any doubt what fate is intended for him: emigration, expulsion or genocide.

Though state-organized crime is still widespread, more virulent is the overarching anonymous instance of ‘the world market’. It declares ever larger sections of mankind to be superfluous, not through political persecution, by command of the Führer or party resolution, but spontaneously, as it were, by its own logic. The result is no less murderous, but the guilty can never be brought to book. In the language of economics that means: an enormously increasing supply of human beings is faced by a clearly declining demand. Even in wealthy societies people are daily rendered superfluous. What should be done with them? The logical status of hallucinations allows that two mutually exclusive realities can find room in the same brain. So it is that many supporters of the life-boat model are simultaneously obsessed by a delusion which expresses precisely the opposite fear: ‘The Germans (French, Swedes, Italians) are dying out.’ Long-term extrapolations of current population statistics are produced to serve as the shaky basis of these slogans. Even though such forecasts have repeatedly proved false in the past, terrible consequences are predicted: an ageing population, decadence, depopulation – accompanied by concerned glances at economic growth, tax revenue and the pension system.

The idea that too many and too few people could simultaneously exist in the same territory causes panic – an affliction for which I would like to suggest the term demographic bulimia.

Analyses from those far-off times when an attempt was made to advance a political economy of migration appear quite comforting in their sobriety compared to the delirious ramblings of the present day. At the turn of the century the American economist Richmond Mayo Smith offered a model example of such cool-headed reflection:

The amount of money brought by the immigrants is not large, and is probably more than offset by the money sent back by immigrants for the support of families and friends at home or to aid them in following. The valuable element is the able-bodied immigrant himself as a factor of production. It is said, for instance, that an adult slave used to be valued at from $800 to $1,000, so that every adult immigrant may be looked upon as worth that sum to the country. Or it has been said that an adult immigrant represents what it would cost to bring up a child from infancy, to the age, say, of fifteen. This has been estimated by Ernst Engel as amounting to $550 for a German child. The most scientific procedure, however, is to calculate the probable earnings of the immigrant during the rest of his ‘lifetime’, and deduct these from his expenses of living. The remainder represents his net earnings which he will contribute to the well-being of the new country. W. Farr reckoned this to be, in the case of unskilled English emigrants, about £175. Multiplying the total number of adult immigrants, we get the annual value of immigration. Such attempts to put a precise money value on immigration are futile. They neglect the question of quality and of opportunity. The immigrant is worth what it has cost to bring him up only if he is able-bodied, honest and willing to work. If he is diseased, crippled, dishonest or indolent, he may be a direct loss to the community instead of a gain. So, too, the immigrant is worth his future net earnings to the community only if there is a demand for his labor.

For a long time there was greater anxiety in Europe about the consequences of emigration than of immigration. This debate stretches back into the eighteenth century. The concept of population as wealth derives from mercantilism. In those days emigration was regarded as a haemorrhage, and the attempt was made to limit, even forbid it. In many states, emigrating, or making it possible for others to emigrate, was subject to severe punishment, a practice which communist states adhered to until very recently. Louis XIV had borders carefully watched in order to keep his subjects in, and in England there was a ban on the emigration of qualified artisans until the middle of the nineteenth century. The so-called Free or Departure Money, an emigration tax imposed on the estates of emigrants, was in force in Germany until 1817, and the Nazis utilized this confiscatory procedure when they did not yet want to murder the Jews, but only expel them.

Ireland is the classic example of a country of emigration. Brutal exploitation by the English led, in the 1840s, to a catastrophic famine, from which the country has not recovered even today. In 1843 Ireland had a population of eight and a half million; in 1961 this figure had sunk to less than three million. In the period from 1851 to 1901 an average of seventy-two per cent of all Irish people emigrated. Ireland remains one of the poorest countries in Western Europe. One can beat one’s brains for a long time over the question of whether emigration is to blame for its poverty, or whether, on the contrary, it improved the situation of the inhabitants.

A naïve but illuminating conclusion is drawn by the anonymous contributor to a lexicon dating from 1843:

Emigration is weak as a remedy against pauperism. If today one could remove all the poor from the lands visited by pauperism, then there would be, should its causes continue to be active, just as many again in twenty years, perhaps in ten. In the main the state should strive to establish and maintain such conditions within its borders, so that at least destitution and dissatisfaction do not drive the people forth.

Emigrants never represent a cross-section of the whole population. ‘It is the man of energy, of some means, of ambition, who takes the chances of success in the new country, leaving the poor, the indolent, the weak and crippled at home.’ wrote Mayo Smith. ‘It is maintained that such emigration institutes a process of selection which is not favorable to the home country.’

This thesis is persuasive. The brain drain, a kind of demographic flight of capital, has devastating effects on countries like China and India, but also on the former Soviet Union. It was of considerable importance in the collapse of East Germany. A large proportion of the Iranian intelligentsia has emigrated in recent decades. The number of doctors from the Third World working in Western Europe exceeds the number of aid workers who are sent to Asia, Africa and Latin America – where there is a shortage of trained doctors – from the states of the European Community.

Better qualified immigrants encounter fewer barriers. The Indian astro-physicist, the star Chinese architect, the Black African Nobel Prize-winner are welcome all over the world. The rich are never mentioned in this context anyway; no one questions their freedom of movement. For businessmen from Hong Kong the acquisition of a British passport is no problem. Swiss citizenship, too, is, for immigrants from any country whatsoever, only a question of price. No one has ever objected to the colour of the Sultan of Brunei’s skin. Drug and arms dealers recognize no distinctions of race and are far above nationalism. Where the bank accounts look good, xenophobia disappears as if by magic. But strangers are all the stranger if they are poor.

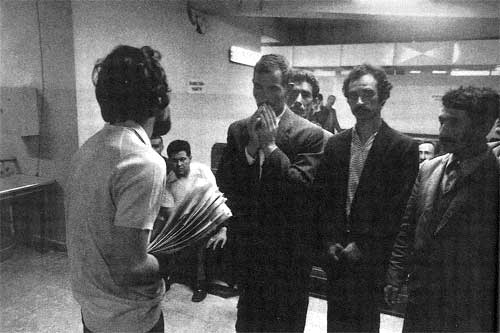

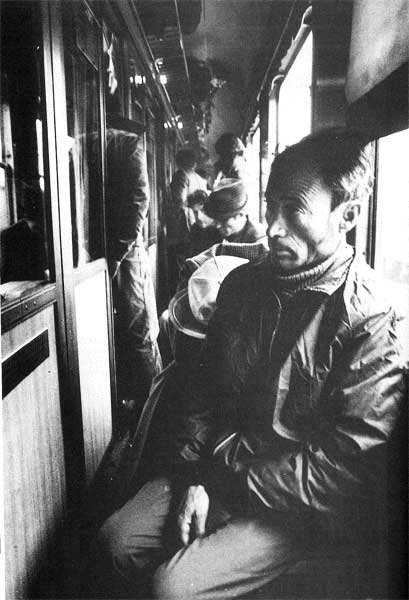

Turkish workers awaiting the results of medicals to allow them to work in Germany.

Of course, the poor are not a homogeneous society either. In all rich countries there are complicated procedures for the control of immigration. They favour those among the poor with very particular characteristics – valued in capitalism–such as knowledge of the world, determination, flexibility and criminal verve. These virtues are indispensable for overcoming bureaucratic obstacles. In other situations sheer physical strength counts. It was only the youngest and strongest of the Albanians who could hold their own against the Italian authorities.

Mayo Smith again: ‘On the other side, it is said that the men who are doing well at home are the ones least likely to emigrate, because they have the least to gain. It is therefore the restless, the unsuccessful, or at least those not fitted for the strenuous competition of the older countries, who are tempted to go.’

That there is some truth in this is demonstrated by the credulous victims of the organized gangs who smuggle people from Asia, Africa and Eastern Europe. They usually have not the least idea of what awaits them. Once arrived, these travellers seem apathetic, as if they had long ago abandoned every hope.

Black markets flourish everywhere there are restrictions. They equalize pressure between supply and demand, without regard for laws, regulations and ethical norms. Since in the real world there are no completely closed systems, illegal transactions can be impeded by controls but never quite prevented. So an illegal trade in human beings has developed in all wealthy countries. However, whereas in classic black markets higher prices are always obtained than in legal trade, the black market in labour follows the reverse logic. Lack does not rule here, but superfluity. Superfluous people are cheap. Clandestine immigration reduces the price of labour.

However, each illegally employed immigrant presupposes an illegally operating entrepreneur. The shadow economy usually works closely with criminal groups that smuggle human beings. In the textile industry, the unskilled sector and, above all, the building trade, practices dominate which are reminiscent of the slave markets of the past.

In some parts of the United States and in the Mediterranean countries of Europe, the shadow economy has so much political power that it is in a position to exert considerable pressure on government. In Germany the authorities turn two blind eyes to illegal employment. Regulations which are supposed to stem immigration are surreptitiously sabotaged, and curious forms of compromise arise.

The size of these slave markets is unknown. No one has any interest in discovering it. The only certain thing is that the unknown figures are very high. In the United States, estimates suggest there are several million illegal immigrants, mostly from Mexico; in Italy, more than a million. Wherever one looks closely it becomes evident that the officially proclaimed ‘policy towards foreigners’ rests on a series of deliberate self-deceptions.

A question arises: does the Great Migration represent a solution, and if so, to which problem? To mention a crude example, would Albania be helped if the active half of its population was admitted to other countries? ‘It is evident [from these arguments] that no general answer can be given to this question.’ That is the amply general conclusion to which Richmond Mayo Smith came in his day. A hundred years later there is little else to add.

Hostel for asylum-seekers, Brandenburg.

Asylum is an ancient convention of sacred origin. It owes its name to the Greeks, though the convention can also be demonstrated in many other tribal societies. It persisted during the Middle Ages: criminals and debtors who had taken refuge in a church could be delivered up to secular justice only with the consent of the bishop. In more recent times, this custom has been increasingly restricted in the Protestant countries. With the modern legal code it has disappeared altogether.

In international law, the first places of asylum were embassies, a tradition maintained until today, notably in Latin America. From the expanded concept of sovereignty, the nation states derived the right to take in non-citizens, who were being politically persecuted in their homeland, and refuse to surrender them. In this case, asylum is not the right of the refugee but of the receiving state. Representative cases of this practice include the rebellious Poles, as well as revolutionaries like Garibaldi, Kossuth, Louis Blanc, Bakunin and Mazzini, who were regarded as criminals in their countries of origin but not infrequently celebrated as heroes in the countries that took them in.

The refugees, whom in Germany we call asylum-seekers or Asylanten – asylants – usually have little in common with such historical figures. Contemporary linguistic usage is influenced by quite another meaning which the word assumed in the Victorian period:

The most frequently occurring asylums, the need for which makes itself felt chiefly in the big cities, are the following: i) for drunkards (inebriates’ homes); ii) for prostitutes (often called Magdalene Foundations); iii) for released prisoners, who are lacking employment; iv) for poor women in childbed; v) asylums for the homeless.

Such places of custody have nothing to do with the original meaning of asylum. They are intended not for strangers to the land, but for stigmatized locals. The only thing these people share with our Asylanten is their poverty.

The idea of asylum has always been ambiguous. Concerns of expediency and ethics, often influenced by religion, have become so muddled that they are difficult to disentangle. In the beginning asylum pertained to robbery, murder and killing: within a clan there was no other sanction but revenge, and whoever did not belong had no rights; asylum – etymologically, the place where one was not robbed – was a makeshift, created in order to meet a need and to make communication beyond tribal boundaries possible.

The immunity of asylum, that is, holds for both guilty and innocent, criminals and victims alike. The moral ambiguity is evident even in the present day. One only needs to think of figures like Pol Pot in Peking, Idi Amin in Libya, Marcos in Hawaii or Stroessner in Brazil, to say nothing of the numerous Nazis, who with the help of the Vatican found refuge in Latin America. Originally this practice may have represented an attempt to provide overthrown rulers with the option of retreat, lessening the risk of civil war. However, as the Cambodian example shows, the granting of asylum can also serve the aim of keeping conflicts alive.

The ‘noble’ asylum seeker is a nineteenth-century idea. In history he is the exception.

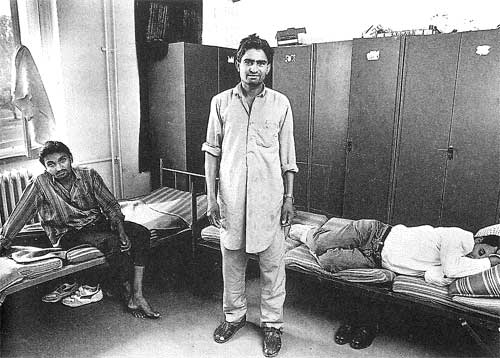

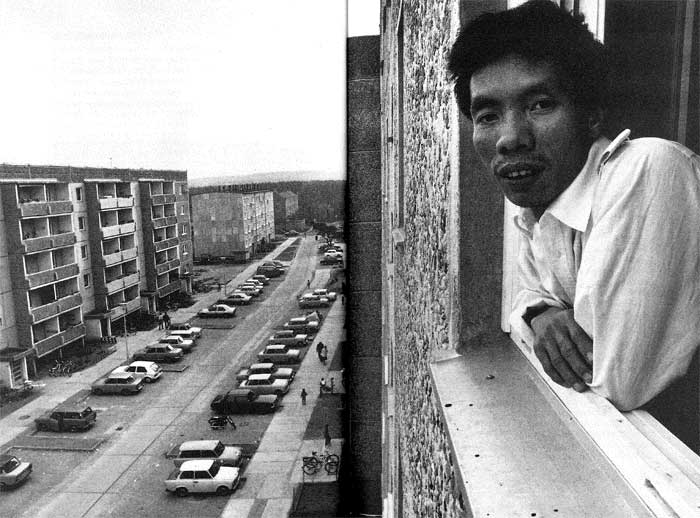

Vietnamese hostel, Malchow, east Germany.

Confusing the right to asylum with other questions of immigration and emigration has fatal consequences. The social and political expansion of the concept of asylum has made the muddle greater. It is not clear why immigrants should be equated with overthrown dictators and criminals on the run or with alcoholics and tramps. In this way the ‘asylum-seeker’ has become a discriminatory, negatively loaded term, a political football.

This confusion, however, turns against those who contrived it, because it contradicts the fundamental idea of asylum to separate the good from the bad, to decide who is a ‘genuine’ asylum-seeker and who is not. The distinction between economic refugees and the politically persecuted is often impossible to draw, and a law which attempts to do so will inevitably be embarrassed. After all, the war between winners and losers is carried out not only with bombs and automatic rifles. Corruption, indebtedness, flight of capital, hyper-inflation, exploitation, ecological catastrophes, religious fanaticism and sheer incompetence can provide as solid ground for flight as the direct threat of prison, torture or shooting.

Germany is a country that owes its present population to huge movements of migration. Since earliest times there has been a constant exchange of population groups for the most diverse reasons. Because of their geographical position, the Germans, just like the Austrians, are an especially varied people. That blood- and race-ideologies gained credibility here, of all places, can be understood as a kind of compensation to prop up an especially fragile national identity. The Aryan was never anything more than a risible construct. (To that extent German racism is different from Japanese racism which appeals to the relatively high degree of ethnic homogeneity of the island population.)

The Second World War mobilized the Germans in more than one sense. Not only did the majority of the male population swarm out as far as the North Cape and the Caucasus (and, as prisoners of war, as far as Siberia and New England), not to mention nearly the whole Jewish population who were forced into emigration and death, but Germany also abducted more than ten million labourers, a third of them women, from all over Europe, so that thirty per cent of all jobs, and in the armaments industry more than half, were done by foreigners. After the war, there were millions of displaced persons; only very few remained in Germany. Compared to these catastrophic movements all contemporary turbulences appear harmless.

Further large-scale migrations began at the end of the war. The number of refugees who, between 1945 and 1950, came into the four occupied zones is estimated at twelve million; in addition there were more than three million ‘resettlements’ from Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union of people who are considered to be of German origin. Between 1944 and 1989, 4.4 million went to the West from the former East Germany. And then, from the mid-1950s, the systematic recruitment of labour migrants – the Gästarbeiter – began which is the principal reason for more than five million foreigners having their legal place of residence in Germany. (The proportion of foreigners is still well below the level recorded by the German Empire before the First World War.) Until the 1980s, the right to asylum was an infinitesimally minor factor in these population movements.

It is puzzling that a population that has had such experiences in its own lifetime can suffer from the delusion that the current migration is a new phenomenon. It is as if Germans had fallen victim to the amnesia observed in the railway passenger model. They are in effect the new arrivals who, having secured their own seat, then insist on enjoying the rights of those who have been there for ever. As is well known, the consequences are more significant than those of a first-class compartment made slightly crowded. Since 1991 there has been an organized manhunt.

Xenophobia – a specifically German problem? That would be too good to be true. The solution would be obvious: isolate the Federal Republic, and the rest of the world could heave a sigh of relief. It would be easy to refer to some neighbouring countries where immigration qualifications are considerably more rigorous than in Germany. But such comparisons are sterile. Xenophobia is a universal phenomenon, and nowhere is it approached rationally. What then is so special about the Germans?

The historical guilt feelings of the Germans, no matter how well founded, are not a sufficient explanation. The causes go further back. They lie in the precarious self-consciousness of the nation. It is a fact that Germans cannot tolerate each other – or even themselves: witness the emotions aroused by German unification. Do these people strike you as the kind who are ready to love their neighbours?

This condition of self-loathing is evident not only in the hostility to foreigners, but also in the opposition to it. Nowhere is a universalist rhetoric more highly valued than in Germany. The immigrant is defended in a tone of utter moralizing self-righteousness: ‘Foreigners, don’t leave us alone with the Germans!’ or ‘Never again Germany!’. Immigrants are idealized in a manner reminiscent of philo-Semitism. Self-hatred is projected on to others –most notably in the insidious assertion ‘I am a foreigner,’ which numerous German ‘celebrities’ have adopted.

It is a curious alliance between the remnants of the Left and the clergy (a similar alliance can also be observed in Scandinavia, which suggests that the stance has something to do with the political culture of Protestantism). While preaching the Sermon on the Mount is the duty of the church, it can’t be passed off as a political solution: whoever calls upon his fellow citizens to offer shelter to all the weary and wretched of the earth – often with reference to collective crimes which stretch from the conquest of America to the Holocaust – without consideration of the economic consequences or regard for whether such a project is realizable, loses all political credibility. He becomes incapable of action. Deep-seated social conflicts cannot be healed by sermons. How many immigrants can a country accommodate? There are too many variables to answer this question but economics provide the best guide-lines. The unavoidable conflicts that arise from large-scale migration are intensified when there is chronic unemployment in the countries of destination. In times of full employment, which will probably never return, millions of labour migrants were recruited. Ten million immigrants came to the United States from Mexico; three million to France from the Maghreb; five million to the Federal Republic, among them almost two million Turks. The migration was not only tolerated, it was emphatically welcomed. The attitude changed only as unemployment increased, even though this was at a time of growing prosperity. Since then the immigrants’ opportunities on the labour market have dwindled. Many are facing a career on the dole. In the face of virtually insurmountable bureaucratic barriers, others have to live illegally; the only prospects open to them are the shadow economy and criminality: prejudice becomes a self-fulfiling prophecy.

A further, underestimated obstacle to immigration is the welfare state. In contrast to America, where no newcomer can count on a social net to catch him, the inhabitants of many European states can claim the minimal safeguards of unemployment benefit, health care and social security.

But the welfare state is under ever-increasing pressure, the safety net has come to be perceived as an association of paying members: its long-term financing is uncertain.

Today there is no point in trying to show that the newcomers are contributors to, as well as users of, the welfare state, or that immigration can have a beneficial effect on the age structure of the population: there is no point because the argument requires a labour market able to absorb the immigrants. In any case, many demographers believe that immigration would have to reach enormous proportions in order to restore the traditional age pyramid. Depending on the model used, it has been estimated that for this goal to be achieved four to ten million younger immigrants per annum would be required for the United States and at least one million for Germany – and Germany could not cope with such an influx, either politically or economically.

Things may get worse. What group is now ready or capable of being integrated with others? The multicultural society remains a confusing slogan as long as the difficulties which it throws up, and fails to clarify, remain taboo. If no one knows, or wants to know, what culture means – ‘Everything that humans do and do not do’ seems to be the most precise definition available – the debate will lead nowhere.

The experiences provided by large-scale migrations in the past are ignored in such discussions. The opponents of immigration deny the examples of success which could be found everywhere, from the Swedes in Finland to the Huguenots, from the Poles in the Ruhr to the Hungarian refugees of 1956. The advocates will not hear of the failures: the civil wars in the Lebanon, in Yugoslavia and in the Caucasus or the conflicts in the American cities. The idea of a multinational state has seldom proved durable. It is perhaps asking too much that anyone remember the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire or the Habsburg Monarchy. But as far as the Soviet Union is concerned, no knowledge whatsoever of history is required; a television is enough. For decades the idea of a Soviet ‘multicultural society’ was inculcated, with a sense of belonging and common goals. The result was an implosion with incalculable consequences.

Dangers can also be observed in the classic countries of immigration. For a long time the new arrivals showed themselves extremely willing to adapt, even if it is doubtful whether the famous ‘melting pot’ ever existed. Most immigrants were well able to distinguish between integration and assimilation. They accepted the written and unwritten norms of the society which took them in, but held on to their cultural tradition – and often also to their language and religious customs – for a long time.

Today it is impossible to count on such an attitude among the old minorities or the new immigrants. Poverty and discrimination, especially in the United States, but also in Great Britain and France, have led more and more groups in the population to insist on their ‘identity’. It is by no means clear what such an insistence is supposed to mean. Militant spokesmen raise separatist demands. At times the slogans fall back on the legacy of tribalism: a Black ‘nation’, an Islamic ‘nation’; in England there is a ‘Muslim Parliament’. Many Blacks in the United States believe that the drug trade is a calculated strategy of the Whites with the aim of exterminating the Black minority.

There are confrontations not only with the majority, but also between the minorities. African-Americans fight against Jews, Latinos against Koreans, Haitians against local Blacks. In some city districts there are virtual tribal wars, and in extreme cases local demagogues claim apartheid as a human right and the conversion of the ghetto into a separate state as their ultimate goal.

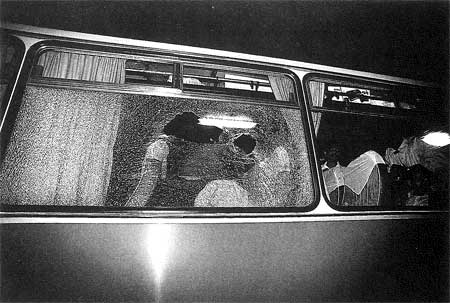

Bus carrying immigrant workers, Hoyerswerda.

Even if the immigrants’ readiness to integrate is decreasing, they are not the ones provoking; conflict originates in the natives. If only ‘natives’ meant simply skinheads and neo-Nazis! But the gangs form only the violent, self-appointed vanguard of xenophobia. The goal of integration has not yet been accepted by large parts of the European population. The majority is not ready for it, indeed at present not even capable of it.

A recent argument against immigration derives, interestingly, from the arsenal of anti-colonialism. Algeria for the Algerians, Cuba for the Cubans, Tibet for the Tibetans, Africa for the Africans – such slogans which helped many liberation movements to victory are now also taken up by Europeans, and not without a certain insidious logic.

It is possible to see, in the idea of a ‘preventive migration policy’, which is intended to remove the causes of emigration, a philanthropic variant of this idea. For that to be successful, it would be necessary to remove the gap between poor and rich countries or at least to reduce it considerably. The task is beyond the economic capacity of the industrial nations, even leaving aside questions of political will and the ecological limits to growth.

That anyone can say out loud what he thinks of the government or the state or the Lord above without being tortured and threatened with death; that disagreements are settled before a court and not by a blood feud; that women can move freely and are not forced to sell themselves or be circumcised; that one can cross the street without being caught in the machine-gun fire of a rampaging soldiery: these things are indispensable. Everywhere in the world the majority want such conditions, and are ready to defend them where they prevail. Without being over-emphatic, one can say these are the minimum conditions of civilization.

In the history of humanity this minimum has been achieved only exceptionally and temporarily. Whoever wants to defend it from external challenges faces a dilemma: the more fiercely civilization defends itself against an external threat and raises walls around itself, the less, in the end, it has left to defend. However, as far as the barbarians are concerned, we need not expect them at the gates. They are always already with us.

The Manhunt

Anyone who intervenes in the political discourses of German public life does so at his own risk. The moral accusations are not the deterrent: they are a proper function of journalism. It is the intellectual risk. Participants in a media debate will nearly always be reduced intellectually, if not made to appear foolish, by the simple fact of their contribution. The reason is not hard to find: whoever submits to the premises of a chat-show is already lost, and has only himself to blame! It is no secret where the rules, to which the participants more or less cheerfully subordinate themselves, come from.

Political debate, which has become more and more ephemeral, evaporates on television, especially where television is at its ‘most serious’: the daily news report on political developments in Bonn. Opposition founders in such conditions: it becomes content with turning the slogans of the opponent on their head.

Nationalistichen Front meeting, Wewelsburg.

Nowhere does this crude pattern emerge more clearly than in the ‘policy towards foreigners’ and in the ‘asylum debate’. (Even these formulations are themselves evidence of the Bonn dung-heap.) Politicians have circumvented this argument in two ways: on the one hand, an abstract moralizing discussion of principles; on the other, complex questions of legal procedure (which are raised when abstractions are exhausted and the prospect of actually doing something is suggested).

Through this strategy, elementary, obvious questions, evidently not in the interests of the politicians to ask, fall by the wayside.

I would like to raise one such question here, which, even if it is not central to the problem of the Great Migration, is a matter of life and death for those who live in Germany–whatever their passport or stamp or legitimacy. It is the question of whether the country is actually habitable. (I call a place uninhabitable where a gang of thugs is allowed to attack a person in the middle of the street or set fire to his house.) Is it possible to live with people who set out on organized manhunts?

My question has nothing to do with the so-called foreigners’ problem or with new regulations for the asylum procedure or with the misery of the Third World or with ubiquitous racism. At stake is the monopoly of force which the state claims for itself.

One can accuse the various governments in the history of this republic of all kinds of things, but no one can say that they ever hesitated to make use of this monopoly of might if it seemed threatened. On the contrary, the executive has never lacked eagerness. Federal Frontier Police, secret services, security task forces, police mobile rapid response units, state and federal detective units have always been on hand with computer dragnets and helicopter squadrons, identikit pictures and armoured personnel carriers. And the legislature has been no less reticent. It has been game to the point of irresponsibility, constantly breaking new legal ground, drafting a law of ‘criminal association’ or banning visits and letters to prisoners awaiting trial.

But in the past months not even the most insignificant use has been made of this arsenal of repression. Indeed, the police and the courts have responded to the mass-scale appearance of gangs of thugs with a previously unheard of restraint. Arrests have been the exception; when carried out, culprits have almost always been set free the following day. The Federal State Prosecutor’s Office and the Federal CID, once omnipresent in the media, devoted to repelling any threats to the German people, have kept silent; it’s as if they have been temporarily retired. The Federal Frontier Police, which only a few years ago occupied every second crossroads, seems to have disappeared.

The politicians, meanwhile, have taken the stage in a new role: they’ve become social workers. There have been pleas for understanding the harsh reality of unemployment; we have been asked to view the killers as being ‘culturally disorientated’ or as ‘poor swine’ who must be treated with the utmost patience. After all, it is hardly possible to expect such underprivileged persons to realize that setting fire to children is, strictly speaking, not permissible. Attention must be drawn all the more urgently to the inadequate supply of leisure activities available to the arsonists.

Such sympathy is astonishing, when one remembers the pictures from Brokdorf (the power station which became the focus of anti-nuclear protest) and Startbahn West (a new runway at Frankfurt Airport, primarily for US military use). At that time, those responsible did not appear to regard the rapid development of discothèques and youth clubs as providing the solution; evidently, in the seventies, uncontested free access to the paradise of leisure society had not yet become an inalienable human right. On the contrary, beating, kicking and shooting were performed with considerable vigour and, if I remember rightly, the state was quite prepared to take a couple of dead in its stride.

Is the sudden change of heart due to a conversion? Since the Enlightenment there have always been humanitarians assuring us that the criminal law is an unsuitable solution to social problems. That can hardly be denied, given the conditions in the jails and the high rate of recidivism, even if the reformers still owe us a convincing alternative. However, the puzzling shift of the state apparatus towards sympathetic lenience for killers is not to be explained in this way. Shoplifters and bank robbers, confidence tricksters and embezzlers, terrorists and extortionists are being sent down as they always have been; no political party has as yet advocated the abolition of the penal code or, even, a thorough reform of the penal system. How, then, do we explain the bewildering gap between enthusiastic prosecution of certain crimes and this new laissez faire approach to others?

Is it possible that the intensity of the effort depends on the interests which the law exists to protect? In the precedents already mentioned it was a matter of the private ownership of real estate, of the right to enlarge airports, build motorways and erect nuclear installations of every kind. In the attacks of recent months, however, the lives of a few thousand inhabitants of the country were at stake. Evidently the agencies of the state consider murder and manslaughter a mere breach of the law, while the removal of a fence is a serious crime.

The circumstances invite other interpretations: is it possible that there are politicians who sympathize with the murderous gangs roaming the country? Is it possible that many observe the manhunt impassively because they imagine that such an attitude could be politically advantageous? One does not, of course, like to believe in such a degree of idiocy, and only the absence of other plausible explanations justifies considering it.

Even the most stupid person, however, should grasp one thing: renouncing the state’s monopoly of force has consequences which might harm the political class itself. One consequence is the necessity for self-protection. If the state refuses to protect threatened individuals or groups, the threatened individuals or groups will have to arm themselves. And, as soon as the resistance has adequately organized itself, there will be gang wars (a development that can already be observed in Berlin and Hamburg). We will all recognize the political conditions: they are the same that Germany experienced towards the end of the Weimar Republic.

Subway, East Berlin.

Photographs © Jean Mohr, Sacha Hartgers, Ali Paczensky, Jean Mohr, Gust, Gust, Detlev Konnerth, Gust, Gust, Sacha Hartgers