It’s a land surrounded by water on all sides, commonly known as an island, not as big as Australia, but not small either. It is mostly flat but embossed with thick forests and two volcanoes, one that goes by the name of Piton de la Grande Chaudière, which was active until 1820 when it destroyed the pretty little town that sprawled down its side, after which it became totally dormant. Since the island enjoys an ‘eternal summer’, it is perpetually crowded with tourists, aiming their lethal cameras at anything of beauty. Some people affectionately call it ‘My Country’, but it is not a country, it is an overseas territory, in other words, an overseas department.

The night He was born, Zabulon and Zapata were squabbling with each other high up in the sky, letting fly sparks of light with every move. It was an unusual sight. Anyone who regularly scans the heavens is used to seeing Ursa Minor, Ursa Major, Cassiopeia, the Evening Star and Orion, but to discover two such constellations emerging from the depths of infinity was something unheard of. It meant that He who was born on that night was preordained for an exceptional destiny. At the time, nobody seemed to think otherwise.

The newborn baby raised his tiny fists to his mouth and curled up between the donkey’s hooves for warmth. Maya, who had just given birth in this shed where the Ballandra kept their sacks of fertilizer, their drums of weed killer, and their ploughing instruments, washed herself as best she could with the water from a calabash she had the presence of mind to bring with her. Her plump little cheeks were soaked with tears.

She never suspected for one moment the hurt she would feel when she abandoned her child. Little did she know how the sharp fangs of pain would tear her womb. Yet there was no other solution. She had managed to hide her condition from her parents, especially her mother, who never stopped rambling on about the promise of a radiant future for her daughter; Maya couldn’t return home with a bastard between her arms.

When she missed her period, she was dumbfounded. A child! This sticky little thing that pissed and defecated on her, here was the consequence of her torrid and passionate nights.

She had ended up writing to her lover Corazón, the Spanish word for heart and a name ill-suited for this chiseled giant. As her third letter had remained unanswered, she had gone to the cruise ship offices, owners of Empress of the Sea, on whose inaugural cruise through the islands she had met Corazón. When she had asked for information at reception, the high yellow Chabeen perched on her high heels savagely interrupted her: ‘We don’t give out information on our passengers.’

Maya had written once more. Once again without an answer. Her heart beat to an intuition. Wasn’t she going to be one of the hordes of abandoned women, women without husbands or lovers, who strove to raise their children alone? This was not what Corazón had promised her. On the contrary, he had promised her the world. He had showered her with kisses, called her the love of his life, and swore he had never loved a woman as he loved her.

Corazón and Maya did not belong to the same class; Corazón was a member of the powerful Tejara family who for generations had been slave owners, merchants, landowners, lawyers, doctors and teachers. Corazón taught history of religion at the University of Asunción where he was born. He bore all the arrogance of a rich kid except this was somewhat subdued by the charm of a gentle smile. Since he was fluent in four languages – English, Portuguese, Spanish and French – he had been hired by the cruise line to give a series of lectures to the second- and first-class passengers.

What annoyed Maya was the dream she’d been having night after night. She saw an angel dressed in a blue tunic holding a lily, the species known as a canna lily. The angel announced that Maya would give birth to a son whose mission would be to change the face of the world. Well, call it an angel if you must, but it was one of the strangest creatures she had ever seen. He was wearing thigh-high shiny leather boots and his curly gray hair fell down to his shoulders. The oddest thing was this protuberance concealed behind his back. Was it a hump? One night in exasperation she had chased him away with a broomstick but he had simply returned the following night as if nothing had happened.

The baby had fallen asleep and he gurgled in his sleep from time to time. The donkey never stopped snorting over the baby’s head. The Ballandras used to put their cow Placida to bed in this stable, but one fine day the poor creature had collapsed on the ground and a thick foam frothed out of its muzzle. Called out in emergency, the vet had diagnosed foot-and-mouth disease.

Turning her back on the baby, Maya slipped outside and walked up the path that wound behind the Ballandras’ house leading to the road. She was not unduly worried because she knew that at this time of night, despite the brightly lit surroundings, there was no danger of her being caught by the couple emerging unexpectedly. They were watching television on a recently purchased fifty-inch flatscreen like all the other inhabitants of this land where there was not much else in the way of entertainment. The husband, Jean Pierre, was sleeping off numerous glasses of aged rum while Eulalie, his wife, was busy knitting a baby’s vest for one of her many charities.

Pushing open the wooden gate that separated the garden from the road, Maya had the impression she was setting off into a zone of solitude and sorrow which would be her lot for the rest of her life.

Setting foot on the macadam, she bumped into Déméter, known throughout the neighborhood for his binge-drinking and bloody brawls. He was accompanied by two of his drunken acolytes who were bawling; they claimed to have seen a five-pointed star hovering over the house. In a great tangle of arms and legs, the three rum guzzlers were floundering in the flood channel where the town’s wastewaters churned. This didn’t seem to bother them and Déméter began bellowing an old Christmas carol: ‘I can see, I can see the Shepherd’s Star.’ Maya ignored them completely and continued on her way, her eyes brimming with tears.

If it hadn’t been for the unusual behavior that evening of Pompette, Madame Ballandra’s dog, a spoilt, arrogant little creature, one wonders what would have happened. Once Maya had gone, Pompette tugged the hem of her mistress’s dress and dragged her to the shed. The door was wide open and Madame Ballandra witnessed an unusual sight, of biblical proportions.

A newborn baby was lying on the straw between the hooves of the donkey who was warming it with its breath. The scene in the stable occurred one Easter Sunday evening. Madame Ballandra clasped her hands and murmured: ‘A miracle! Here is the gift from God I was not expecting, I shall call you Pascal.’

The newborn was very handsome, with a dark complexion, straight black hair like the Chinese, and a delicately delineated mouth. She hugged him to her breast and he opened his green-gray eyes, which were the color of the sea that surrounded the land.

Madame Ballandra went out into the garden and walked back to the house. Jean Pierre Ballandra saw his wife returning with a baby in her arms and Pompette jumping around her heels.

‘What do I see here?’ he exclaimed. ‘A child, a baby. But I can’t see whether it’s a girl or a boy.’

Such a remark may surprise the reader if they didn’t know that Jean Pierre Ballandra had poor eyesight and had already downed a good many glasses of neat rum. He had also worn spectacles since the age of fifteen when a guava branch had pierced his cornea.

‘It’s a boy,’ Eulalie told him bluntly, then she took him by the hand and forced him to kneel beside her. They struck up a blessing since they were both firm believers.

—

Jean Pierre and Eulalie Ballandra formed an unusual couple, he with African blood and she, pink-skinned, originating from a rugged isle where the population was said to be descended from Vikings. What occurred in their hearts, nevertheless, was something else. They worshipped each other despite the many years living together. Because of Eulalie, Jean Pierre had never had a woman on the side, a common practice, widely respected by all his fellow countrymen. For years, he had made love to his one and only woman. As for Eulalie, Jean Pierre was her only reason for living. The couple remained childless despite constant visits to the gynecologist. Eulalie’s younger years had been scarred by miscarriages until finally her menopause made her mercifully sterile.

Jean Pierre and Eulalie were comfortably well-off. They lived mainly off the income from their nursery, with the banal name of The Garden of Eden. Jean Pierre was a genuine artist. Among other plants, he had produced a variety of Cayenne rose, as a rule a fairly ordinary flower, but the one invented by Jean Pierre had amazing velvety petals and, above all, a delicate, penetrating scent. As a result, it was much in demand by the Social Security and Employment authorities as well as by soup kitchens. Jean Pierre named his Cayenne rose ‘Elizabeth Taylor’ since when he was younger and out of work, he would kill time as best he could at the movies and was especially fond of American films. On seeing his favorite actress in Cleopatra he gave her name to the flower he had created.

The arrival of Pascal in the family was a big event. Early next morning, Eulalie made the rounds of the shops and bought a pram as spacious as a Rolls-Royce. She stuffed it with blue velvet cushions for the baby to lie on. Every day at 4.30 p.m. she left the house and made her way to the Place des Martyrs. Situated facing the sea, the square resembled a window cut out from the town’s baroque architecture.

Eulalie breathed in the sea air and contemplated the green-gray waters, which frothed as far as the eye could see. Eulalie had always dreaded the sea, that majestic bitch which mounted guard at every corner of the land. But the fact it was the same color as her son’s eyes suddenly brought them closer and made them almost friends. She remained a long while staring at it, thanking it for its company, and then headed back to the Place des Martyrs.

The Place des Martyrs was the very heart of Fonds-Zombi and was lined with sandbox trees planted by Victor Hugues when he came to restore slavery following orders from Napoleon Bonaparte. Eulalie walked up and down the crowded paths and made the rounds several times before sitting down near the music kiosk where the town’s orchestra played popular melodies three times a week. The women sitting near her never failed to admire her little son, thereby filling her heart with pride and joy.

What a hubbub around the Place des Martyrs! Crowds of teenagers, boys and girls alike, playing truant from school, groups of unemployed men spouting forth pedantically, and nursemaids dressed to the nines keeping watch over the babies dribbling and sucking on their bottles as well as cheeky little brats running in all directions.

Everyone stood up to peer at the pram Eulalie was pushing. People were staring for a number of reasons. Firstly, Pascal was remarkably lovely. Impossible to say what race he was. But I must confess the word race is now obsolete and we should quickly replace it by another. Origin, for instance. Impossible to say what his origin was. Was he White? Was he Black? Was he Asian? Had his ancestors built the industrial cities of Europe? Did he come from the African savannah? Or from a country frozen with ice and covered in snow? He was all of that at the same time. But his beauty was not the only reason for people’s curiosity. A persistent rumor was gradually gaining ground. There was something not natural about the event. Here was Eulalie, who for years had worn her knees out on pilgrimages to Lourdes and Lisieux, blessed with a son from our Lord, and on Easter Sunday no less. This was by no means a coincidence but a very special gift. Our Father had perhaps two sons and sent her the younger one. A son of mixed blood, what a great idea!

The rumor gradually took Fonds-Zombi by storm and reached the outer boundaries of the land. It was a hot topic in the humble abodes as well as in the elegant, wealthy homes. When it reached the ears of Eulalie, she gladly welcomed it. Only Jean Pierre remained inflexible, considering it blasphemy.

—

When Pascal was four weeks old, his mother decided to have him christened. One fine Sunday, Bishop Altmayer walked out of his Saint Jean Bosco residence and left the orphans in his care on their own, while the church bells pealed out. Eulalie had dressed her baby in a fine white linen blouse with an embroidered smock plastron. His tiny tootsies wiggled in his gold-and-silver-thread knitted bootees and on his head he wore a bonnet which illuminated his little angel face. The christening had all the pomp of a wedding or banquet and was attended by three hundred guests dressed to the nines, including the children from the catechism class all in white, waving small flags the colors of the Virgin Mary. Shortly after the dessert of multi-flavored ice creams, an unknown visitor turned up. Everyone who saw him was surprised by his appearance. He was dressed in a somewhat outmoded pinstripe suit, and by way of a tie he wore a kind of ruff. On his feet were a pair of shiny turned-down boots like the ones worn by Alexandre Dumas’s three musketeers. Even stranger, he seemed to be hiding something odd behind his back, perhaps a hump. The stubble of a graying beard covered his chin.

He made straight for Eulalie who was grinning like a Cheshire cat and holding a glass of champagne. ‘Hail Eulalie full of grace,’ he declared. ‘I am bringing a gift for the child Pascal.’ Thereupon he held out the package he had been carefully holding. It was an earthen vase containing a flower, a flower that Eulalie, though she was the wife of a nurseryman, had never seen before. It had an amazing color: light brown, the color of a light-skinned Capresse, with curly, velvet-like petals, wrapped around a delicate sulfur-yellow pistil. ‘What a lovely flower!’ Eulalie exclaimed. ‘What a strange color!

‘This flower’s name is Tété Négresse,’ the new arrival explained. ‘It is designed to erase the Song of Solomon from our memory. You recall those shocking words: I am Black but I am beautiful. These words must never be pronounced again.’

Eulalie did not understand the meaning of his objections. ‘What are you trying to tell me?’ she asked in surprise, but the silence told her that the speaker had already disappeared. She found herself alone, holding her gift and thinking it was all a dream.

Upset, she ran to join Jean Pierre who was laughing and drinking champagne with a group of guests. She told him what had just happened.

‘Don’t you worry,’ he said shrugging his shoulders. ‘It was probably just an admirer who didn’t dare express his real feelings. I can make good use of this flower.’ And he kept his word; soon The Garden of Eden could boast of two marvels: the Cayenne rose and the Tété Négresse.

When Pascal reached the age of four, his mother decided to send him to school. It wasn’t because she was tired of showering him with kisses or seeing him caper about and play with Pompette or burst into the nursery. But because education is a precious asset. He who wants to succeed in life must acquire as much as possible. Jean Pierre and Eulalie had suffered too much for having been deprived of it.

At the age of twelve, Jean Pierre was already spraying a landowner’s banana plantations with sulfate while Eulalie, at an even younger age, was seated beside her mother selling the fish her father had caught: blue fish, pink catfish, red snapper, yellowtail snapper, grouper, sea bream and blue-fin tuna.

Pascal was therefore admitted to the school run by the Mara sisters. The Mara sisters were twins whose mother was a well-known figure since she served at the presbytery and every Good Friday took to her bed showing the stigmata of Christ’s Passion on both hands and feet. It was no secret that her two daughters were the children of Father Robin, who had managed the parish for many years before conveying his old age to a retirement home for priests located near Saint-Malo. At that time, the priests could get away with such behavior. There were no American or French movies like Spotlight or Grâce à Dieu. Everyone turned a blind eye to transgressions against God’s commandments.

The school run by the Mara sisters was an elegant building situated in the middle of a vast, sandy courtyard where the pupils ran around excitedly during recreation. On his first day Pascal wore a blue-and-white suit with matching shoes. The sisters welcomed him effusively, well aware of the splendid catch they had made. However, they soon became disillusioned.

Pascal turned out not to be the kind of pupil they were expecting. He would daydream in class, mixed only with the poorest children, and had nothing better to do than dash into the kitchen where two underpaid servants prepared the school lunches. He would lavish them with caresses and kind words. In return, they showered him with little treats. If Eulalie hadn’t been on good terms with the Mara sisters, they would have expelled him.

The day after his fifth birthday Eulalie took Pascal to the shed at the bottom of the garden while Jean Pierre, always lackadaisical, followed them dragging his feet. The shed was extremely clean. The sacks of fertilizer and weed killer were heaped in one corner, whereas the floor was covered with white gravel. Eulalie turned to Pascal.

‘I have an important confession to make. I love you, that you know, but I didn’t carry you in my womb. And you are not a product of his sperm either,’ she added, pointing to Jean Pierre.

‘What are you trying to say?’ Pascal exclaimed, dumbfounded.

He found it difficult to comprehend such an unusual story. Although most of the children on the island did not know their father, they knew full well who their mother was. She was the one who worked herself to the bone, slaving away to buy their clothes and send them to school.

‘What I want to say is that one Easter Sunday we found you in this shed and adopted you as our son.’

‘Who are my real parents?’ Pascal asked, his voice brimming with tears.

It was then that Eulalie told him about the rumors of where he came from.

It’s strange that for many years Pascal attached little importance to this confession and even less to the stream of gossip that reached his ears regarding his origins. He knew he was born in a land of the spoken word where lies are stronger than truth. Then, for no reason at all, he began to lend them an ear, for it is better to be the son of God than the son of beggars. It then became a veritable obsession.

He would stop and gaze at the sky. The heavens had opened up a second time and the mystery of the Incarnation had taken shape. This time the Creator had taken care to make His son of mixed blood so that no race might take advantage over others, as has happened in the past. The weak point was that He didn’t explain to His flesh and blood what was expected of him. What was he expected to do with this world streaked with bomb attacks and scarred with violence?

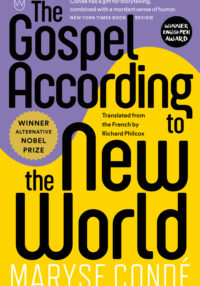

Artwork: Adolf Hölzel, Nativity, 1925, courtesy of Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main