My names is Agnès, but that is not important. You can go into an orchard with a list of names and write them on the oranges, Françoise and Pierre and Diane and Louis, but what difference does it make? What matters to an orange is its orange-ness. The same with me. My name could have been Clémentine, or Odette, or Henrietta, but so? An orange is just an orange, as a doll is a doll. Don’t think that once you name a doll, it is different from other dolls. You can bathe it and clothe it and feed it empty air and put it to bed with the lullabies you imagine a mother should be singing to a baby. All the same, the doll, like all dolls, cannot even be called dead, as it was never alive.

The name you should pay attention to in this story is Fabienne. Fabienne is not an orange or a knife or a singer of lullabies, but she can make herself into any one of those things. Well, she once could. She is dead now. The news of her death arrived in a letter from my mother, the last of my family still living in Saint Rémy, though my mother was not writing particularly to report the death, but the birth of her own first great-grandchild. Had I remained near her, she would have questioned why I have not given birth to a baby to be added to her collection of grandchildren. This is one good thing about living in America. I am too far away to be her concern. But long before my marriage I stopped being her concern – my fame took care of that.

America and fame: they are equally useful if you want freedom from your mother.

In the postscript of the letter, my mother wrote that Fabienne died the previous month – ‘de la même manière que sa sœur Joline’– in the same manner as her sister. Joline had died in 1946 in childbirth, when she was seventeen. Fabienne died in 1966, at twenty-seven. You would think twenty years would make childbirth less a killer of women, you would think the same calamity should never strike a family twice, but if you think that way you are likely to be called an idiot by someone, as Fabienne used to call me.

My first reaction, after I read the postscript: I wanted to get pregnant right away. I would carry a baby to term and I would give birth to a child without dying myself – I knew this with the certainty that I knew my name. This would be proof that I could do something Fabienne could not – be a bland person, who is neither favored nor disfavored by life. A person without a fate.

(This desire, I imagine, can only be truly understood by people with a fate, so it is a desire akin to wishful thinking.)

But you need two people to get pregnant; and then two people do not necessarily guarantee success. Getting pregnant, in my case, would involve looking for a man with whom I could cheat on Earl (then what – explaining to him a bastard would still be better than a barren marriage?), or divorcing him for a man who can sow and reap better. Neither appeals to me. Earl loves me, and I love being married to him. The fact that he cannot give me a child may be disheartening to him, but I have told him that I did not marry him to become a mother. In any case we are both realists.

Earl left the Army Corps of Engineers after we moved back from France, and now works for his father, a well-respected contractor. I have a vegetable garden, which I started in our backyard, and I raise chickens, two dozen at any time. I was hoping to add to my charges some goats, but the two kids I acquired had a habit of chewing the wooden fence and running away. Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is not Saint Rémy, and I cannot turn myself back into a goatherd. ‘A French bride’ is how I was first known to the local people, and some, long after I stopped being a new wife (we have been married for six years now), still refer to me by that name. Earl likes it. A French bride adds luster to his life, but a French bride chasing goats down a street would be an embarrassment.

I gave up the goats, and decided to raise geese instead. Last spring, I acquired my first two, a pair of Toulouse geese, and this year I purchased a pair of Chinese geese. Earl read the catalogue and joked that we should go on adding American geese and African geese and Pomeranian geese and Shetland geese each year. Let’s have a troupe of international brigands, he said. But he forgot that the two couples will soon be parents. In a year I will be expecting goslings.

The geese, more than the chickens, are my children. Earl likes the geese, too, and he was the one to suggest that we give them French names. His French is not as good as he thinks, but that has not stopped him from speaking the language to me in our most intimate moments. I always speak English to the people in my American life. I speak English to my chickens and geese.

The garden produces more vegetables than we can consume. I share them with my in-laws – Earl’s parents and his two brothers and their families. They are all nice to me, even though they find me foreign, and perhaps laughable. They call me Mother Goose behind my back. This I learned from Lois, my sister-in-law, who is unhappily married and who hopes to turn me against the Barrs family. I don’t mind the nickname, though. It may be insensitive of them to call a childless woman Mother Goose, but I am far from being a sensitive or sentimental woman.

When Earl asked about my mother’s letter, I told him about the birth of my grandniece, but not the death of Fabienne. If he detected anything unusual, he would assume that another baby’s birth reminded me of the void in my life. He is a loving husband, but love does not often lead to perception. When I met him, he thought I was a young woman with no secrets and few stories from my childhood and girlhood. Perhaps it is not his fault that I cannot get pregnant. The secrets inside me have not left much space for a fetus to grow.

I was in such a trance that I forgot to separate the geese from the chickens at their mealtime. The geese had a busy time terrorizing and robbing the chickens. I chastised them without raising my voice. Fabienne would have laughed at my incompetency. She would have told me that I should simply give the geese a good kick. But Fabienne is dead. Whatever she does now, she has to do as a ghost.

I would not mind seeing Fabienne’s ghost.

All ghosts claim their phantom skills: to shape-shift, to haunt, to see things we don’t see, to determine how the lives of the living people turn out. If dead people had no choice but to become ghosts, Fabienne’s ghost would only scoff at the usual tricks that other ghosts take pride in. Her ghost would do something entirely different.

(Like what, Agnès?

Like making me write again.)

No, it is not Fabienne’s ghost that has licked the nib of my pen clean, or opened the notebook to this fresh page, but sometimes one person’s death is another person’s parole paper. I may not have gained full freedom, but I am free enough.

‘How do you grow happiness?’ Fabienne asked. We were thirteen then, but we felt older. Our bodies, I now know, were underdeveloped, the way children born in the wartime and growing up in poverty are, with more years crammed into their brains. Well-proportioned we were not. Well-proportioned children are a rare happenstance. War guarantees disproportion, but during peacetime other things go wrong. I have not met a child who is not lopsided in some way. And when children grow up, they become lopsided adults.

‘Can you grow happiness?’ I asked.

‘You can grow anything. Just like potatoes,’ Fabienne said.

I thought she would have given a better answer. Growing happiness on the top of a maypole, or in a wren’s nest, or between two rocks in a creek. Happiness should not be dirt-colored and hidden underground. Even apples on a branch would be better suited to be called happiness than apples in the earth. Though if happiness were like apples, I thought, it would be quite ordinary and uninteresting.

‘You don’t believe me?’ Fabienne said. ‘I have an idea. We grow your happiness as beet and mine as potato. If one crop fails, we still have the other. We won’t be starved.’

‘What if both fail?’ I asked.

‘We’ll become butchers.’

Such were the conversations we often had then, nonsense to the world, but the world, we already knew, was full of nonsense. We might as well amuse ourselves with our own nonsense. If the thumb on the left hand got crushed under a hammer, would the thumb on the right feel anything? Why did god never think of giving people ear-lids, so we could close our ears as we shut our eyes at bedtime, or anytime when we were not in the mood for the chattering of the world? If the two of us prayed with equal seriousness but with the opposite requests – dear god, please let tomorrow be a sunny day; dear god, please let tomorrow be an overcast day – how did he decide which prayer he should honor?

Fabienne loved making nonsense about god. She claimed she believed in god, though what she meant, I thought, was that she believed in a god that was always available for her to mock. I did not know if I believed in god – my father was an atheist and my mother was the opposite of an atheist. If I had been closer to one or the other, it would be easier for me to choose. But I was only close to Fabienne. Perturbatrice of god, she called herself, and said I was one, too, because I was always on her side. In that sense we were not atheists. You had to believe that god existed so you could make mischief and upend his plans.

‘If we can grow happiness, can we also grow misery?’ I asked her.

‘Do you grow thistles or ragworts?’ Fabienne said.

‘Do you mean misery grows by itself, like thistles and ragworts?’

‘Or by god,’ Fabienne said. ‘Who knows?’

‘But happiness, can it grow by itself?’

‘What do you think?’

‘I think happiness should be like thistles and ragworts. Misery should be like exotic orchids.’

‘Only an idiot would believe that, Agnès,’ Fabienne said. ‘But we already know you’re an idiot.’

I did not tell Fabienne then that I thought our happiness should be like the pigeons M. Devaux kept. They went away, they came back, and what happened in between was no one’s business. Our happiness should not be rooted and immobile.

M. Devaux: I should say a few words about him. He, like Fabienne, begins this story, but he was already in his sixties when we were thirteen. I suspect that he is dead now. He should be. Fabienne is dead, and he should not have more rights to life than she.

M. Devaux was the village postmaster, an ugly and sickly-looking man. Fabienne and I had paid as much attention to him as we had paid every adult, which was very little. We liked his pigeons, though. For a while we talked about keeping a pair of pigeons ourselves. One would go with Fabienne to the pasture during the day, one would accompany me to school, and they would fly over the fields and alleys, delivering our messages to each other. But the scheme, like that to grow happiness, entertained us for some days and was then replaced by a new one. We never seriously carried out any of our plans. It was enough to feel that we could, if we wanted, make things happen.

One day Mme Devaux died. She had been a robust woman, younger than her husband, coarser and louder. It was said that she had never been ill for a day in her life, until she came down with the fever. Three days and she was gone.

I do not remember if they had children. Perhaps M. Devaux could not give her a child. Earl cannot be the only man who has to endure that fate. Or their children had grown up and left the village before our time. The questions that did not occur to me to ask at thirteen feel important now. I wonder if Fabienne knew the answers. I wish I could ask her. This is the inconvenience of her being dead. Half of this story is hers, but she is not here to tell me what I have missed.

Mme Devaux was buried on a Thursday, that I remember. A funeral was not an excuse for Fabienne not to take her two cows and five goats to the meadow, or for me not to go to school. But in the evening, we went to the cemetery, looking for the freshest grave. There was more than one new grave that fall.

On the way there, Fabienne gathered some marguerites and gillyflowers and handed the bouquet to me. We were not the kind of girls who put flowers in our hair or made wreaths out of boredom, but if someone caught us wandering in the cemetery, we would say we were leaving flowers for Mme Devaux.

I do not think Fabienne explained the necessity of the flowers to me. I simply understood it. Back then we often knew what we were doing without having to talk things over between ourselves. But was it such a surprise? We were almost one person. I do not imagine that the half of an orange facing south would have to tell the other half how warm the sunlight is.

When we found the patch of fresh dirt, Fabienne took some of the flowers from me. There was a bouquet left near the wooden cross, and she scattered our flowers at the foot of the grave, one at a time. ‘Some flowers to hem into your robe,’ she whispered. ‘And these are for your slippers.’ I imitated Fabienne, though I did not say anything to the dead woman. We did not know Mme Devaux well. Most adults struck us as peripheral, some more annoying than others. But we liked the ceremony, the grave of a recently dead woman strewn with the more recently dead flowers.

Afterward, Fabienne lay down on a stone nearby. I arranged myself next to her, looking at the inky blue sky and the stars, as I believed she was doing. The stars, those we could see with our eyes and those we could not see, had been named, but my learning that fact at school did not help us at all. Fabienne had not made the stars into a story or a game for us, and I knew exactly why: the stars were too far away, and they looked too much alike.

Neither of us spoke. Underneath us were a couple who had lived and died long before our time. We preferred the cemetery at nighttime. During the day there were often people around, old women in black with brooms, a caretaker cleaning away the stale flowers. It was not that we minded being seen, but we believed that ghosts, if there were any, would not show themselves to us if someone else was around.

It was October 1952. Fourteen years have passed since then. Soon I will be many decades removed from Fabienne. But years and decades are mere words, made-up names for units of measurement. One pound of potato, two cups of flour, three oranges, but what is the measuring unit for hunger? I am twenty-seven this year, and I will be twenty-eight next year. Fabienne was, is, and will always be twenty-seven. How do I measure Fabienne’s presence in my life – by the years we were together, or by the years we have been apart, her shadow elongating as time goes by, always touching me?

The evening air was chilly, and the stone underneath us retained no warmth from the day. I felt the cold in my body. It was a different kind of cold than when we jumped into the creek too early in the spring. The shocking iciness of the water would take our breath away, but only for a moment, and then we would scream with giddiness, the air in our lungs making us feel strong and alive. On the gravestones, the cold was heavy, as though it were not us who were lying on the stones, but the stones lying on us. I listened to Fabienne’s breathing, which was becoming slower and shallower, and I tried to match mine to hers.

She must have been as cold as I was. I waited for her to sit up first so I could follow. Sometimes we lay on the gravestones for a long time until our bodies turned stiff, and afterward, we had to jump up and down to warm ourselves, our bones and teeth rattling. Fabienne believed that we must always test the limits of our bodies. Not drinking until thirst scratched our throats like sand. Not eating until our heads were lightened by hunger. There was not much to eat, in any case. Some bread, and, if we were lucky, a piece of cheese. Sometimes we would face each other and hold our breath, counting with our fingers, seeing how long we could go and how red we would turn before we had to take our next breath. When we lay on the gravestones we did not stir until we felt as cold and immobile as death. If we wait to do something until it becomes absolutely necessary, Fabienne had explained to me, we will leave little opportunity for the world to catch us. Catch us how? I had asked, and she had said that she saw no point explaining it if I could not understand. Just follow me, she had said, you do nothing but what I tell you to.

‘What do you think M. Devaux is doing at this moment?’ Fabienne sat up and asked.

I felt a rush of gratitude. I would not have been surprised if she had decided not to move until sunrise. I would have had no choice but to lie next to her. My parents, unlike Fabienne’s father, would have noticed that I had missed my bedtime.

‘I don’t know,’ I said.

‘Let’s pay him a visit,’ Fabienne said.

‘Why? We don’t know him.’

‘He needs something to occupy himself. All widowers do.’

Fabienne’s father was a widower, so she must have known something about widowers. ‘What can we do for M. Devaux?’ I asked.

‘We can tell him we come to offer our friendship.’

‘Does he need friends?’

‘Maybe, maybe not,’ Fabienne said. ‘But we’ll say we need him to be our friend.’

‘Why?’ I asked. Back when Fabienne still went to school, some girls used to ask to be our friends, but they had quickly learned the humiliation of wanting something from Fabienne, who would study the girls with a malicious curiosity and then speak slowly: I don’t understand how you came up with the notion that we want you as a friend.

‘A man like M. Devaux can be useful,’ Fabienne said. ‘We can say we want his help to write a book.’

‘A book?’ Fabienne had not been to school for the past two years. Sometimes she studied my readers to keep up with me, but neither of us had seen a real book in our lives.

‘Yes, we can write a book together.’

‘About what?’

‘Anything. I can make up stories and you can write them down. How complicated can it be?’

It was true that I could write my letters better than Fabienne. In fact, my handwriting was good, and every year I won the school prize for penmanship. And it was true that Fabienne could make up stories about pigs and chickens and cows and goats, and birds and trees and Mère Bourdon’s window curtains and Père Gimlett’s horse cart. And Joline, Fabienne’s older sister, who had died a long time ago. I no longer remembered what Joline looked like, but Fabienne had several stories made up for Joline’s ghost, and the ghost of her baby. Fabienne called him Baby Oscar even though he had died before there was time for anyone to come up with a name for him. And then there was the ghost of Joline’s American sweetheart, Bobby. Bobby, who was a Negro, had been court-martialed and hanged after Joline got pregnant.

All those deaths had happened when Fabienne and I were six going on seven. I remembered Joline whipping Fabienne and me with a bundle of nettles when she caught us sneaking behind her and Bobby, and I remembered the chocolates he had thrown to us, to make us stop following them. Fabienne and I talked about what Bobby was doing to Joline in the Jeep or when he drove with her to someplace we could not reach by foot. We tried to act those things out according to our imagination. We felt old enough for everything in the world, including the stillborn baby, his color darker than our nanny goat Fleur. Fabienne and I both touched his head, sticky and gray and lukewarm, when all those women’s attention was on Joline, who was bleeding and dying quickly, making terrible noises.

In Fabienne’s stories, all three of them were all right now, not really a happy family, but three happy ghosts, busy with their own games.

The ghosts gave me a chill sometimes, but more often they made me laugh. Look there – Fabienne would point to the creek – did you see? What? I would ask. I knew I would never see anything she saw, and it was for that reason I could have no other friend but Fabienne. She was eyes and ears for both of us. It’s Baby Oscar, she would whisper; he’s lancing eels with a bayonet. Oh, he’s learned swimming, I would say, and Fabienne would reply that she wasn’t sure how good a swimmer he was, as he was sitting on that lily pad like a frog. In other stories, Joline’s ghost wove willow branches into a snare and caught any man leaving the bar too late at night. What did she do with them? I asked. She tickled them so they couldn’t stay drunk easily, Fabienne would say; do you know how funny and terrible it is for those men when they cannot focus on being drunk?

And then there was Bobby’s ghost, my favorite. He blew air into a cow’s ears. He tied the tails of a litter of piglets together and threw a firecracker at them. He put cigarettes under children’s pillows and stuffed fragrant soaps in men’s pants. He hid oranges behind the rocks or in the woods. The oranges, in Fabienne’s stories, were always for us only. In truth we had seen oranges no more than a handful of times in our lives, back when Bobby was still alive. The first time he brought an orange for Joline, Fabienne sent me to beg her to let us hold the fruit in our hands for a moment. We had never seen anything in that color till then.

I never made up stories, but I was good at listening to Fabienne.

Every story has an expiration date. Like a jar of marmalade or a candle.

Does marmalade have an expiration date? Yes, marmalade only makes fruit live longer, not forever.

Does a candle have an expiration date? It may not come with one, but once past a certain point in its life, it is corrupted, even if it still burns.

Time corrupts. And we pay a price for everything corruptible: food, roof beams, souls.

This story of mine expired when I heard of Fabienne’s death. Telling a story past its expiration date is like exhuming a body long buried. The reason for doing so is not always clear to everyone.

I have been thinking about Fabienne’s baby. My mother did not say in her letter if that baby survived his or her birth. Nor who fathered the baby. Certainly my mother saw no point in sharing the information. Perhaps she has even forgotten my friendship with Fabienne. More often now my mother, in her letters, includes the news of this or that death from the village. She has long accepted that I will not return to Saint Rémy during her lifetime. Her hope, she said in one letter, is that I will at least return for her funeral.

Perhaps I should plan a visit to Saint Rémy. Earl would not grudge me the fare. If I lie on Fabienne’s stone, I wonder if I will feel the same heaviness as we once did. There will be no waiting for her to decide when to stand up and walk away. Any choice will have to be mine: to up and leave, or to remain immobile above her grave forever.

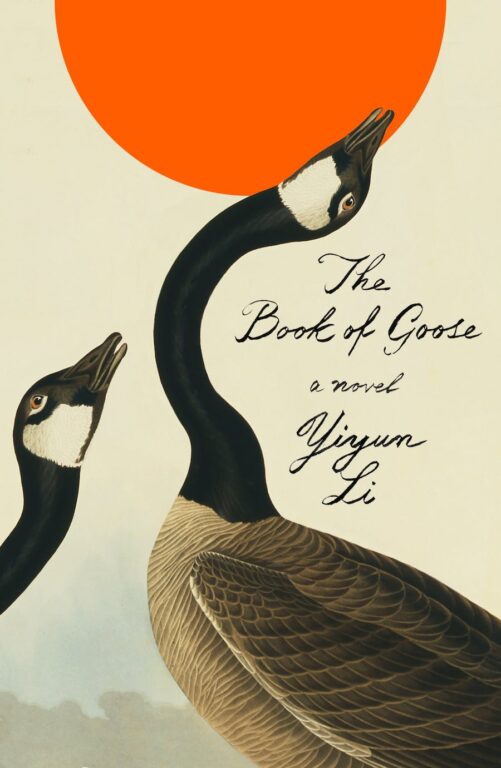

Image © Frans Vandewalle

This is an excerpt from The Book of Goose by Yiyun Li, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US.