Two of us have been watching telly and as of last minute I’m the one heading to the shop. A game of rock paper scissors is usually what it takes for me and my housemate Hannah to decide who’s doing what between us, and now I’ve lost the best of three rounds I’ve to peel myself from our duvet nest and get going. You enjoy it, I say. Hannah says she will, her head dunking back into the covers, her phone a periscope that’s snapping a picture of my defeat. Post that and you’re dead, I tell her. I’m in my comfiest clothes, greasy hair balled into a bread roll shape on top of my head, and no one needs to see that. I slide into our other housemate Smurf’s bubble jacket that I know he won’t mind me borrowing, then I take the angora scarf from the peg in Hannah’s room. I won’t, Hannah calls out. She’s such a liar.

It’s gonna piss it down, you know when the atmosphere gets thick? I hurry along the secret way behind the row of beaming takeaways that are always busy at this time of night. The secret way T-bones the road where the petrol station is, the petrol station being the only place that’s open: home of the six-quid bottle of plonk and the gummy sweets I’ve been sent in search of. It’s just about light and it’s absolutely freezing, and because I don’t fancy running into Buzz tonight, I sink into my hood as I pass the Embassy, the back yard of which is the arena for more fag breaks than Buzz’s allowed, impromptu vomitings and the odd knee trembler between the bar manager, Lorraine, and Jack, the owner, who Smurf sells coke to. Buzz’s one of those suggestive guys who doesn’t have the guts to ask you anything outright. After making me privy to the staff discount last night – which resulted in an unforeseen kiss that he probably foresaw all along – I can’t say I’m that fussed about hearing what he has to suggest to me this time. It’s not that Buzz isn’t nice and everything. It’s more that he’s missing that combination of cynicism and vulnerability that really gets to me. What I’m saying is the guy’s got no fucking edge.

The alleyway’s dingy, rape city. I dig my key out, get the jagged bit sticking between my index and middle fingers and walk as quickly as I can. The cobbles remind me of toads: several thousand toads packed in filmy rows. There’s a broken TV stand as well, propped against some bins. Above that’s a cat, a haggard thing that looks like a living twist of rope. I’ve been wary of cats ever since I watched an episode of this TV programme where the main characters are this dweeby yet kind of cool group who investigate paranormal goings-on in apple-pie America. One of the cagey, business-suited guys the gang are always hunting said, as they cornered him in an alleyway, his voice verging on the manic, that the Devil is always in the background and his favoured messengers take many forms. Then he lifted this cat from behind a metal bin, and the cat had an awful goblin face, gold eyes with no pupils and a forked tongue. This one’s mewling. I hiss at the bloody thing, watching it bristle and flow along the wall before pausing to stare back at me, unknowable. When I hiss again the cat scarpers, and I’m on my way.

At the bottom of the alleyway shines a taxi, an old man struggling out of it. You can’t miss confusion like that. The way the guy’s hands are going for the wall at his hip, it’s as if he’s a live current in need of earthing. Even from here I can see his bottom lip going, Buh Buh Buh, the taxi leaving him to grope his way along the bricks. He’s at least sixty, his posture’s a total nightmare and his hair’s marshmallow-grey at the temples and darker, slicked up top. Honestly, does anyone who’s not a pensioner still use a comb?

I’ve a roll-up on the go so I finish that while I decide what to do. A few tokes and the smoke’s crushed against a toad and I’m heading over, asking the guy if he’s all right.

His I sounds like an E and he doesn’t pronounce his H’s. ’Ave you got et? he says.

Got what?

He’s gazing, no idea what at.

You lost, mate? I say. You need a hand?

Oh, he says, obviously trying to say, Oh no, except not getting to the no part. And although I can’t really be doing with this any more, I say, Here y’are, where you off to? Which entrance: A, B, C or D? Then I point at the doors of a carroty-coloured block of flats about ten metres away from where we’re stood.

Matey-boy’s eyes bulge: cloudy discs of colour on either side of a nose mangled by what has no doubt been a lifetime on the sauce. His expression makes me wonder if I’ve done the right thing going over like this, because you worry, don’t you. You’ve got to worry, what with men being the way they are. This old guy’s studying the flats harmlessly enough and I know I shouldn’t be nervous because I can stick up for myself, I’ve had to, but it’s something to think about, isn’t it? Because let’s face it, a man can grab you if he wants, or say something, and a lot will do and there’s potentially nothing we can do about it. I mean whether it’s the shortcut down the secret way that I just took or anywhere in a place like the valley where you can easily find yourself on your own, there’s a chance you’re going to spot someone coming the other way at some point, some strange bloke, and no one could blame you for being on your guard. That’s why even with this confused pensioner standing in front of me the doubt still seeps in. I become the spun coin. What I do now is look him in the eye and ask which door he’s after. Which door’s yours, mate? I say. This feels important because you should always try to do what people think you can’t do, and you should always go out of your way to shake the worry off and go where you want, when you want. In this way putting fear out of your head can become a feminist act. A vital rebellion.

This one, the man replies before dawdling in the direction of door B, checking over his shoulder to see if I’m still there, which I am. It takes him ages to get to the door. It takes him forever with the fob, as well, and no word of a lie, he’s dead chuffed when the receiver bleeps green and the lock snaps open.

Click.

He enters the foyer, I don’t. We’re at the brink of some concrete stairs and I can smell stale hash. Shit, the smell’s coming from Smurf’s coat. I check the inner pocket and there’s a joint docked-out there prematurely, which is another thing this old boy hasn’t a clue about.

His hand is on the banister. Please.

Please what, mate?

Oh. He’s staring, not seeing. A colourless flap of chewing gum sits on his tongue.

Go on then, I say, pointing at the cavernous stairwell. Go on, off you go.

He doesn’t move. He just stares. I ask him what’s up again, laughing to myself when his mouth opens like he wants something chucking in it. I notice a cut on his chin from where he’s had a clumsy shave, and I’m becoming conscious of the time, because it’s a Sunday and I haven’t got all night. I’ve to be at Tatt’s Haulage tomorrow for five or Sharon will go spare and give my shift to someone else.

Look, I can’t help you if you don’t tell me what’s up, man.

I—

Go on. Time to get yourself home.

Oh.

Bollocks to this. I step out onto the street and the door nearly shuts behind me, and that’s when the man speaks up, his voice taking on a real heartbreaking note of frustration.

I just don’t know where I am, he says.

I search that raddled face for lies and turn nothing up. Every wall of this lower stairwell has been tagged with marker pen. CRUSTYMAN, the walls say, next to a scraggy picture of a beardy face that could be a drawing of the great outdoors in human form. It’s mental seeing a thing like that on concrete. It’s almost like it belongs to another era, another mindset entirely, and it can see right through me: the face of a God that we might have forgotten, but who still remembers us. If the face’s eyes were coloured they’d definitely be green. My mouth’s gone well dry and the lights have timed out. I step in front of the sensor and bring brightness back to the stairwell, revealing a blue rubbery handrail that if you were to fall against would hurt easily as much as the steps. It’d be just my luck for this guy to fall and hurt himself. I take the poor bastard by the elbow.

We go upstairs, me assuring the guy that blah blah blah, and so on, then we’re outside of what I guess must be the place. A plasticky door leads into a wall. Hey presto, the guy’s key fits the lock and the door opens directly into a sitting room that smells like mouldy bread.

Now, this flat, well, bear with me here, but let’s just imagine for a minute that every person’s life’s a river, right? You’ve your streams, rills and becks, and say that’s some people. Then you’ve got great sunny winders like the River Nile, choppy rapids, sewers, even, or them ice rivers you get off the telly, the ones that go through glaciers that are pretty much the bluest things you’ve ever seen. Now imagine that these rivers are other people’s lives, then remember that they come together, you get confluences, then remember that they sometimes split apart again like nothing ever happened. Either that or they keep flowing until there’s no real difference between them. Now these rivers flood into the sea. Every fucking one. Some might take a while, head wherever. Others might stretch further, go slower, but at the end of the day they all end up in the one place. Well, I take one look at this guy’s flat and I can tell straight away that he’s come to the end of his course. This guy’s about five minutes from becoming one with the salt. I step indoors and scour my feet on the heavy twill rug. Our two rivers have crossed tonight and now I’m going to have to get on with it.

There’s a couch and a coffee table, a booth of an adjoining room with a single bed, a kitchen and a pisser and nowt on the walls. No signs of a life save the telly. Everything’s as plain as a block of Cheddar cheese.

On the coffee table though is what looks like one of them barrels you fetch raffle tickets or bingo balls out of. So there’s that as well. Look, it’s for medication. There’s a note sellotaped to the table with a smiley face on it; in gangling biro letters it’s reminding the poor bastard to cheer up.

I give the dispenser a spin. Nothing comes out. That’s when I notice the digital panel. Ah, so when the timer goes, the machine gives the guy what’s necessary. Who needs a wife, eh? Forget companions.

I help him out of his coat. He’s shaped like a bloody Easter egg. Sitting on the couch like he doesn’t know what it is.

You all right, mate?

Oh.

Fucking oh. The guy takes it in. He takes me in: the skinny pants, cream, which Hannah says suit my complexion, and Smurf’s coat: a puffer jacket. Purple, massive and warm.

I’ll make him a drink then do one. Tea?

The man nods.

Yeah, man. A brew, yeah? You want one?

The man smiles. I suppose people will never forget tea.

What’s your name? I ask on my way to the kitchen. I’m Samirah.

I?

Your name, mate? I say, turning around.

The man wrings his spotted hands. He’s forgotten the question.

Through the kitchen window above the sink I can see the petrol station. The bright banded sign makes a picture of the drizzle. Below it are empty streets, steep potholed roads and the occasional pollarded tree. Cheap rent and a council that handed out hackney cab licences then didn’t check whether you operated in the borough brought my parents to the valley. Although Mam and Dad’s marriage was arranged by their families before I was born, they were lucky because they ended up loving each other. Skids moved in next door, one neighbour said, talking on his phone the day we arrived, going into himself when he realised I’d overheard him. I remember the cardboard box sagging in my arms. It had sat on the pavement for ages, its base soaked through, my stuff trying to escape out the bottom. I stared the neighbour out but I never actually said anything. You don’t, do you. Or at least I never used to. At that moment I knew my dad had been right when he’d told my mum that I’d get a good education if we moved to the valley, although what I learned wasn’t exactly what he had in mind. Dad’s old school. He can’t appreciate that you can class yourself as having been taught something if you know not to take things too seriously. Considering how bothered he was about coming here and how demanding he was when it came to me doing well in school, Dad never once took the time off from his taxi to come to parents’ evening, and he even had the nerve to go into a week-long sulk when he found out I’d been eating hotdogs from the ice-cream van at lunchtimes.

There was fuck all he could do about that. He’d wanted this life for me, that’s what he got. You might want things on your terms, I said to him. That’s not how it works. Course I’m a veggie now – those poor pigs! – but as a teenager school was hotdogs. It was Mars bars and Panda Lemonade, a fumble in the basement cloakrooms with any older lad who was up for it. It was Lambert & Butler in smokers’ corner behind the sixth form common rooms, my initials bound up with my mate Charlotte’s in a love heart on the fence. Charlotte moved away and had a kid at sixteen, while I sacked school off altogether. I haven’t seen her since – it would only be weird now. Mad how things go. The way people neglect each other.

Mildew on the sill. Pure grime. Outside, a mile or so past this middling strip of civilisation, the countryside begins, rising out of the night like a killer whale, stone terraces tucked here and there with people in them. Man, you should see this place in summer. Not that we’re anywhere near that time of year. The window opens enough for me to lean out of, so I spark Smurf’s joint up using the hob and have a smoke from two storeys up while the kettle boils. Course there’s no milk. There’s no mugs either. Just mouse shit sprinkled all over the cupboard shelf and a pair of glass tumblers. I wash the tumblers under the tap then dry them with a bit of tissue from my pocket as the wind chucks itself against the building. What a thing it must be to lose your marbles on your own, with not even enough milk in the fridge for a proper brew.

In the living room I set the man’s tumbler of black tea in front of him then ask if there’s anybody I can call. When he instinctively grabs for the drink, I try to stop him before he burns his fingers on the hot glass, but I mistime my swipe and we both end up getting scalded. The tea slops onto the table and leaks into the smiley face, staining it brown. As the man gawks at me like I fucking did that on purpose. I point at my burnt hand and ask if there’s anyone who can come and help him instead of me. Or will he be all right on his own now?

He’s dead confused, fuck’s sake. Daughter, he says, while I’m towelling the spilled tea dry with a minging rag from the radiator.

I’ve—

Is she local, mate?

Joanne—

I look at him.

Joanne . . . She lives in . . . Reading.

Reading. You got a number? I reply, making a goofy ‘phone’ signal with my pinkie and thumb. I sound like a nurse. I remember waking up in casualty once after necking a bladder of sangria around the back of the spiritualist church when I was about thirteen. One of them talked to me the same way. I know she meant well, I still swung for her.

The phone trills. I’m that edgy after the spliff that I jump. Old boy does too. His head jerks as if his skull’s tethered to a bungee cord. The ringing fills the whole flat – it’s a horrible sound, the sound of the years trilling by, crashing to a halt when you least expect it.

Will you answer the phone, please?

I’m not answering your phone, man.

Oh, please.

No.

PLEASE, will you just answer the phone?

Distress is enough to make me do anything. I’ve not used a house phone in years. Hello? I say, shaking my head when an American voice answers me, male.

Hi there.

I’ve never chatted to a real Yank before. I imagine him with his gun and Bible. I suppose he’s picturing me with my wonky teeth, thinking life owes me a living.

Wow, he says, once I’ve explained the situation. That’s good of you. Thank you for stopping.

You’re all right, I say, picking at a stain embossed on the wall. It comes off, taking a patch of wallpaper with it.

He’s my uncle, the Yank clarifies. My mom and I have a weekly phone call arranged. He’s not doing so good . . .

Well, duh.

Excuse me?

I twiddle the spiral cord flex. Look, is there no one you can call, mate? No one who can come sit with this guy? I’ve things to do.

The American exhales. There’s his daughter and whatnot. She’s—

Joanne’s in Reading.

Of course, you’re right. Wait, hold on a second . . .

A conversation I can’t decipher twitters from thousands of miles away. Then this woman comes on the line. Like my host, with his shop dummy expression, peering at nothing in particular, each hand clamped upon each knee, the woman is the owner of a mixed-up accent. She thanks me: Thank yew, and calls me sweetheart. Such a kind thing you’re doing, helping my brother.

Bruth-er. Maybe she’s right. I weigh this act against the things I’ve done, the things I will do. I suppose it’ll be one to stack in my favour when the time comes. And that’s something, isn’t it. I’ll take that. Every single one of us, we take what we can get.

No worries, love, I say.

The woman promises to find help. I ask if she wants to speak to her fuddled sibling but she doesn’t hear me, and that’s when it occurs to me that not only do I not know this man’s name, the family haven’t thought to tell it me. How often do they think of their brother? How important is he to them? Are they getting on with their lives already, moving on before he’s even gone?

I offer him the phone. Your sister.

My?

Your fucking sister in America.

The man tears the phone from my hand and slams it in the cradle.

Hey!

Bathroom.

What you on about?

Bathroom.

No.

BATHroom.

He’s already on his way to the pisser, which has no door. He’s unbuttoning his trousers, or at least trying to, stopping midway, Oh, fumbling, getting all agitated, and he might be about to wet himself here and then where will we be?

Come here, I say, holding my breath as I help the guy get his trouser button undone. The icy burnish of the naked pisser bulb sets me alight as I’m helping this lost codger pull down his trousers. When the deed’s done I shudder into the sitting room, anxious to leave the man with some shred of, I want to say dignity, then I retreat to the kitchen where I sit at the table and picture a river shrieking into the ocean, into a sea bigger and colder than any other.

Enough’s enough. I’m about to leave when I spot a keyring attached to some keys in the empty fruit bowl. It says, If you find this man lost, please call this number. Like a stray dog, I can’t help but think, pressing in the digits on my phone.

It’s another old boy in the end, a puny guy with mole-eyes and wrinkles that spread outward as if his nose is a stone dropped into the pond of his face. He hesitates at the sight of me and I can tell what he’s thinking, but no way am I giving him a reaction.

All right, I say. He’s in there. I point at the toilet. Just in there.

Right. The man slips off his coat as he enters the flat.

Just in the toilet.

Okay. Yes. Fine.

The man glances past me, unwilling to make eye contact.

I’ll be on my way then.

What?

I said I’ll be on my way.

Finally the man looks at me. I’m at the door by this point. By the way, he says. You’ve done a good thing, helping my pal.

You’re all right. I nod. He’s just a bit lost, isn’t he.

Aye, the man agrees. He is that.

The way it goes though, at his age.

The man runs a hand down his face. Do this often, do you?

I . . . How do you mean?

I’m just surprised. Your lot. You never normally get involved, do you?

I don’t reply.

I mean, most of the time you keep yourselves to yourselves. I wouldn’t have thought you’d have stopped when you saw him like this. Most of you wouldn’t bother.

I think I say yeah. I think I agree. I’ve grasped the door handle when the man asks me what’s wrong.

Nothing, I say. I’m all good.

The guy starts apologising. He starts saying he’s sorry if I’m offended and he didn’t mean what I think he meant and yeah, yeah, fucking whatever, mate.

He comes over and touches my arm. He has this magnified expression on his face. Timid, yes, and yet hate is there.

I can’t move. I can’t speak. My head’s gone fizzy and there’s this hysterical feeling that reminds me in a way of when a microphone gets too near a speaker. For a terrible moment I’m completely exposed and it takes a hell of a lot of willpower to pull myself together, but when I do, I rip my arm free and tell the man it’s fine. I’ve gotta go, I say. I need to get out of here.

Really, I—

You’re all right, pal. I wipe his clamminess on Smurf’s coat. He’s gone all quiet. Fuck’s sake. Now I’m feeling guilty. He’s making me feel like I’ve made him feel weird. Have I gone mad or something? Am I being mental?

He’s a stubborn old bastard, the man says as I get the door open. He nods at our mutual friend, who has by now hiked his trousers up and is pottering into the living room as if his ankles are shackled together. He knows not to drink, he does it anyway. Every day he’s out, boozing alone.

Can’t say I blame him.

The man goes to the window. Suppose.

Right.

The man hesitates. Well.

What?

You know . . .

What?

Nothing.

I flick my hood up. Sound, mate.

Wait, the man says. He looks so lost. I was just going to say that, well . . . you’re a sweet little thing and you really remind me of—

I walk out. The first one, the dying one, he is climbing slowly into bed.

A bitter darkness has descended upon the valley. I loosen Hannah’s scarf and face the rain. It’s almost as if a giant diamond has broken into smithereens up there, and now the most brilliant shards of neon are floating all over the show. No way can I be bothered with the garage now. I head back the secret way, treading on petrified toads until I come to the broken TV stand, which makes me stop, because in the stand’s cracked glass the street lamp on the corner is madly reflected. It’s a crazy thing to see in this frame of mind. It makes me imagine that a bomb’s gone off in a parallel universe and somehow the explosion’s been caught in a time lapse in the glass. It’s pretty beautiful, so lovely in fact that maybe it’s more than an explosion. Maybe it’s a comet captured as it sears its route through deep space. Yeah, that’s what it is. It’s a fading star and I’ve never noticed it before tonight, and the only place I or anyone else will ever be able to see it is here in this lonely valley where the countryside has begun to reclaim what the town took. There’s no doubt about it. I can hear the ocean heaving as I crouch in front of the cracked pane in the TV stand. I’m wishing the light was warm, but it’s not, it’s cold. It’s the simple chill of a mossy sheet of glass. A noise makes me jump. It’s that cat. It’s staring at me from the wall with this look on its face. Now I can hear footsteps. They’re heavy. Getting closer. And I can hear waves, the sea.

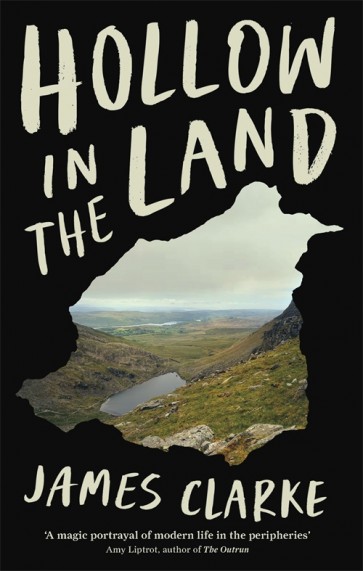

‘Some Rivers Meet’ is included in James Clarke’s Hollow in the Land, published by Serpent’s Tail.

Image © Surreal Name Given