Mother’s Soups

It never occurred to my Mothers to take me to see any doctor about my hip. They had their own special remedies. I remember how they’d creep past in the yard, and come back with some cup of muck-water, say, sprig of elderflower, or even a bit of chipped bark. Put these things – pfft! – put them in with yeast, and – ha! – celery in with his bathwater . . . or else . . . good rub with khafaf . . . No! The bones will grow as they will . . .

All these mad panaceas, Mister, and sheer invention. It’s a real mystery as to why the same creativity couldn’t once have been brought to the kitchen. The only thing we ever ate were variations of terrible soups.

My Mother Sadaf might have been a gardener, Mister, but a cook she was not. My old burly Mother cooked soup in huge batches in a big black pot she called her cubby. She made leek and lentil soup for our lunches. Carrot soup with a mountain of butter at bedtime. Breakfast was always bread and butter alone, with great fistfuls of salt. Salt went into everything. I remember sitting on the kitchen counter imitating the way the long slow sound of red Saxa with its shhhhhh . . . came pouring into the pot. That amount of salt, Mister, consumed as it was, every day for so many years, rendered all our tongues a little numb.

One of my Mothers would call us and bash a ladle come dinner time. I’d hear the others rattle down banisters, their bangles and bare feet going, their perfumes mingling with the steam coming off the pot on the stove, and then they’d all arrive with a bowl in hand to dip and to serve. They’d fly in and out of that grubby kitchen. Scooping mouthfuls between cusses, insults and bursts of sudden laughter. No table to sit around. And never any room besides. Not with all the filthy laundry, bits of machinery and gardening tools left leaning on doors, old chairs, and picture frames stacked against sad-looking cupboards. Instead, we slumped into spaces left on the floor in the telly room. Legs stretched out in front of the set – and oh, what about your British telly, Mister? Your bunk-spilling, myth-making machine . . .

Yes – so many memories of them early days appear to me now, with the lot of us, sat in front of the telly. It was more an education into what lay beyond my Mothers’ house. Beyond the allotment even, and into the proper bright-wide. All them British plots. Them bawdy British comedies and soaps. Them repeats of your Open All Hours, say, or your ’Allo, ’Allo, and Steptoe and Son on BBC Two. My Mothers used to wrestle for the remote, throw spoons even, and spill tea over the cushions, just to decide what to watch.

My Mothers Shahnaz and Sofiyya, for instance, preferred American melodramas to them soaps. The ones with waxy faces and flashy clothes, Mister – your Dynasty, say, or your Dallas. My Mother Aneesa preferred the savagery of animals or people – gameshows like The Crystal Maze or Ready Steady Cook. My Mother Miriam enjoyed Dr Quinn and The Darling Buds of May, while my Mother Sadaf, whenever she appeared from work in the yard, never really took any notice. Most evenings, my Sisi Gamal would emerge from his basement, all squinting and irritated by the light, to try, usually in vain, to convince my other Mothers to switch the telly to the Nine O’Clock News.

No matter what was on, Mister, I enjoyed how everyone spoke over one another. All that muddled English over the telly, mixed with Arabic and bits of Dari. They all tore at each other’s plates, dousing hard bread into watery soup. I’d slurp whatever they’d poured for me. And then my Mother Sadaf might come around with her ladle looking to spill the last of her dregs, and I’d offer mine. I’d always laugh at the way she’d accidentally dip a tit into her bowl as she served out. She never noticed it herself. She’d just carry on boot-faced, orange blotches darkening the ends of her enormous breasts. Nobody else spoke up either. It was enough just to watch it happen, night after night, giggling and nudging at each other, but saying nothing.

After dinner, we’d wash our own bowls in the sink. My Sisi Gamal often stayed on with me on the sofa. If he still hadn’t won over my Mothers, he’d storm off and head back into the basement: Ach! – I’ve had enough of your idiot-box! You women watch what you want . . . You can forget me! My Mothers would barely register, Mister, sitting glued to the set. The little aerial sticking out the back of it. That cold blue glow against their faces. My Mother Miriam looking down at me going Owf . . . your uncle is so dramatic.

Idiot-Box

Your British telly taught me a lot, Mister. Not just because I couldn’t read or write at that age – and it was, honestly, my only way of finding out what was going on in the world – but also because it was in front of that telly that my Mothers began to reveal themselves to me.

My Mothers’ house was not a quiet place. It was laughter one night, weeping the next. Although, my Mothers tended never to dredge up the pasts of their own sob stories. What they complained about was lives here in Britain. How miserable they all were. How they loathed their jobs, Mister, the nothingness each day offered, in the kitchens, minding other people’s children, and cleaning rich people’s homes.

It was through the telly, Mister, that I learned how my Mothers saw themselves – or at least how they’d like to see themselves and each other. Programmes which never reflected their own likenesses, not really, but in the fortunes of your Penelope Keith, say, or Lynda Baron, my Mothers still found their own refractions.

For instance, I was very confused when once, Mister, in an episode of Open All Hours, your Granville and Arkwright pretended to be Chinese. They put bin lids on their heads and started speaking nonsense. My Mother Aneesa and Mother Shahnaz started doing the same, balancing parathas on their heads and falling about in laughter. At other times there were scenes that brought a strange kind of nostalgia. I remember this one, went my Mother Miriam once, when the old man falls in the stairs and hurts himself . . . my abba was a drunk like him. Sad like him too. And my Mother Aneesa, Mister, would laugh and reminisce about her uncle Faris anytime Mr Bean was on. Faris was good in the heart, she’d say, but he could not talk because – ha! – the policeman shot him in the neck!

These stories were a way for my Mothers to tell of their lives, Mister. To speak of things they couldn’t or wouldn’t otherwise mention. They’d even assign British types to one another. Mother Shahnaz was Mrs Bucket as she was forever on show. And Mother Sofiyya was her lustful sister Rose. But they all had their stories, Mister. Some sibling cousins in Ramallah say, some Mohammad and his brother Hamed in Nablus, some Farouk and brother Jabir from Jenin, who reminded them of Del Boy and Rodney flogging cheap wares off a lorry in their youth.

Widows

I also noticed how the telly started patterning my Mothers’ speech. Little expressions, say, that were once so beautifully mangled now began to flatten out into imitation. My Mother Sofiyya, for instance, after coming home from scrubbing floors, make-up smeared and eyes all baggy, made mention of some so-and-so, some high-waisted woman she’d worked for all day.

Esh – such a pain, she’d say, bloody woman thinks she is a queen-bee!

What’s the pain, this queen-bee? my Mother Shahnaz would ask.

Bloody fussy, fussy when there is nothing to fuss! She wears the white slippers, ah? I don’t hear when she comes. And when she comes I am resting. For two minutes I am resting! But then she comes and says if I want to rest, I should go home . . . Bloody-cheek!

Esh-esh! You tell her buzz-off, bloody bucket-woman!

Bloody feather-duster!

And they’d laugh, Mister, with their noses upturned in the air. At times it was this simple. Just the odd bit of idiom: bloody-cheek, queen-bee, not-on-my-eiderdown. But then there were other storylines in them endless soaps and period dramas and so on which seemed to stir old memories. Stories involving adulteresses and scheming wives sent cushions flying. Soups were left to go cold and spill over. I remember my Mother Sofiyya screaming at the telly once Chi-chi! – this little bitch! before barricading herself in the toilet, where we could all hear her crying.

You might put this down to sentimentality, Mister. I’m not so sure.

I say this because whenever a heroine ended up with what she wished, some love story ending in marriage, say, their moods would blacken. They’d sit with hands tucked in their laps, just shaking their heads at the impossibility of happiness. I’d even go further to say it was tragedy alone that satisfied them. When Samir was killed just before marrying Deirdre Barlow in Corrie, my Mother Fareeda tutted at the telly, as if to say he had it coming. I remember my Mother Aneesa too, her thick eyebrows trembling: Good, the Samir boy is dead – ha! – with this bloody white cow? – Yes, yes, better off dead than married . . .

My Mothers wanted to cast themselves as widows, I think. Tragic widows, Mister, with cobwebs, and dead flowers in their hair, surrounded by ruin and rubble. But I never knew who or what they were mourning. I learned to listen, anyway. To how it all came out in borrowed metaphor and phrases. In stories that were not their own, but in which they made room for themselves regardless.

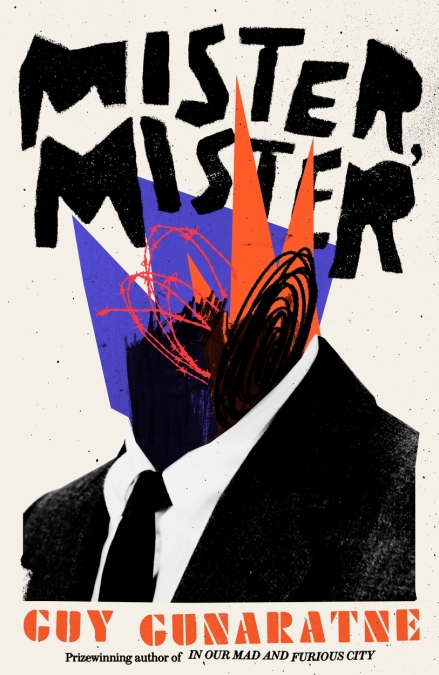

Image © Darren Hester