In 2013 Sarah Hall was named one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists. She is the author of five novels and two short story collections. Tessa Hadley has contributed stories regularly to the New Yorker since 2002, and her most recent collection is Bad Dreams. They discuss the short story, their creative processes, and the magic and medicine of literature.

Sarah Hall:

I remember talking to you once, Tessa, about styles and qualities of prose we both enjoy reading, and the phrase ‘quiet realism’ came up, and then later ‘lambent realism’. I took from this the idea of the importance of linguistic accuracy and how it equates to meaning, to fictional veracity. What I admire about your work, and what seems incredibly well suited to the short story form, which loves the shadow-world of the ordinary, is the sense that under the words and phrases your prose has deep, resonating energy, a sense of disquieting tension and truthfulness. When you are composing first drafts, is there an awareness of that duality – the surface, constructive level, and what is going on underneath? Or is that like asking an alchemist to separate out her ingredients after the business of making gold?

Tessa Hadley:

That’s such an interesting question – and it’s one readers often ask, don’t they? All those layers of meaning, which good readers can find in a rich piece of fiction – in what ways are the writers aware of deploying those? Do writers work in a sort of fog of inspiration, or are they building their meanings like structural engineers? So I’m really thinking hard about what the unfolding of meanings feels like as I write. Of course it’s not quite either of those two, the fog or the structural engineer (more like the fog perhaps). But I think what I’m aware of first and foremost as I’m choosing words, making sentences, trying to get the timing and pacing of the scene right, is the story. I’m thinking about getting the scene right, making it feel true. That requires fighting against the inertia of language, fighting back against what’s shorthand, or corny, or fake. You’re seeing and feeling the scene – or the exchange, or the person or place – in imagination: and you’re feeling for the magic words which will release the truth of that element in the story onto the page. So it isn’t the theme, or anything like it, that I’m feeling for. If there’s a theme, then it’s embodied in the stuff of the story and will come onto the page through getting the stuff of the story right. But of course I’ve chosen the story in the first place – or it’s chosen me – because it seems rich with theme, with point. And in every sentence at some level of awareness I’m negotiating with that underlying point . . .

Your stories often work at one remove from ‘reality’ – like ‘Mrs Fox’ in your new collection, where a wife turns into an animal. And yet the marvellous close observation of the fox, making her physicality feel true – and her husband’s visceral responses too – seems just as crucial to making the dream-picture work as in a more conventionally realist story. Do you think that’s right?

Sarah:

Yes! How hard one has to try to persuade if the dream is to seem true! And the true-dream is how I think about all fiction perhaps. Literature is that odd paradox: an artifice that somehow truthfully engages the reader, the mind, the emotions, the self, in essential communion. The world of a story can seem more real than the cup of tea left to cool on the table while one reads. The atoms of the teacup, and the subatomic scales of thought and imagination! In ‘Mrs Fox’, I was highly aware of having to convince a reader that a woman has turned into a vixen. Not so difficult once she has become the vixen, when claw shape and waxy tallow of fur can be described, but that moment of change, of transformation – what to do about that? At what moment does human bone become fox bone? How? How to create the spell using language? Were the story a fairytale, the business could be done in one simple line – ‘and then she turned into a fox’ – Ta-da! I suppose my solution was to attempt some kind of legerdemain using sound, repetition, incantation. Running, running, running, and rhyme. I remember reading Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy. It’s the only book since childhood that I’ve finished then had to sleep with the light on – no joke. Something happens at the end of the novel, occult linguistic trickery. Something is summoned via language – horror, a vortex in the soul, a sense of a devil in the room. The section of my story in question is a much, much lesser version, of course, but I’m trying to say that alongside visual description and ciphering of word as thing, it is the musicality of language, its cadence, scaling, its pulses and percussion, that can create trance, dream state, and ultimately belief. I have always liked the idea that there are no hard borders between prose and poetry.

And here I would love to ask you about what you ‘hear’ when you write, the noise in the author’s head. The voice of the words and . . . what else? I’m often feeling my way along a new sentence because the consonants and the vowels and the differing length of words is helping to create a sound effect, which will create a literary effect. I remember being given Sunstroke while I was recuperating from major surgery. I was in a narcotic fugue, and feeling that awful, post-traumatic, bodily vulnerability. I remember reading the stories and it felt like some kind of recuperative musical acupuncture. Those exact sentences, that seemed to have such clear resonance, a cordant quality (is that the opposite of discordant?), cut through everything groany and noisy and furry. And there I was, back in the world, but in the world of the stories, which felt tantamount. We speak sometimes of writers having a tin ear, but you seem note-perfect. Even when we read privately and silently, don’t words have primordial sound in the mind? Could you talk a little about the instrument of language – what are you playing internally?

Tessa:

I like the ‘true-dream’, as a description of fiction. There’s less distance than readers sometimes think between ‘realism’ and fiction that deploys some ‘unrealistic’ magic. Realism is so unrealistic, actually, so artificial: and writers, if they’re any good, are intensely and pleasurably aware of deploying that artifice. Getting a character out of an imaginary room and into an imaginary garden – or out of a swimming pool and into a changing room, or across a sped-up twenty years of life – is just as strange, really, and as much of an effort of imagination, as turning her into a fox! Yet through that artifice, just as you say, the story can come to seem more real than actual tea in an actual world! Wonderful magic.

When I was reading your transformation of the woman into the fox, of course as a writer I was alert to your difficulty as it loomed ahead in the story – how will she do it? And I thought you managed it with consummate skill. At just what moment, among those words printed in black ink on the page, does the woman-form become fox-form, in front of our mind-eye? Somewhere between the words, is perhaps the answer: in the gap between them, I saw that miracle happening. And it’s just the same, describing, let’s say, a face – or a flash of anger or attraction between lovers. You place the right words on the page, exactly the right words, and in the gap between them, conjured by the reverberations they set up in their new relation to one another, the face or the flash will come into its being.

And then you talk about how crucial sound is to that ‘rightness’, which makes the thing seem present, makes the illusion. And of course you’re right. And Wittgenstein says something wonderful about us choosing the right word by its smell (mostly I don’t understand him but I feel a kind of intuitive sympathy with how he writes about language). And I want to add in sight. I know that when I’m looking at a paragraph I’m struggling with, I need to see it differently, against a dark background on the screen, smaller, and I squint at it, and at a certain moment everything seems to be at last in the right place, in the right arrangement, giving off the right colour. But of course I don’t just mean the shape of the words on the page, or what’s seen with the eye merely. I wouldn’t recognise its rightness if it was in Russian or Spanish. I seem to be seeing the meaning, the words are all giving off their reverberations of meaning and association, and they’re wound together into new relations of energy, in long coils of syntax.

So perhaps what we need as our reference here is a seventh sense. (Not a sixth one, that’s reserved for seances and prophecies.) A seventh sense: the one deployed when we stare and stare at the page and think, it’s not right, something’s missing, something’s inert or false in here. A seventh sense that perceives the meaning of art writing as coming into its being through form and patterning, though not quite as in a picture or in music. ‘Light rustled under the blue surface . . . The water was coldly radiant.’ (In the lido, from your story ‘Luxury Hour’.) And then, because you don’t want the colour of your prose to be too exquisite, the guard, ‘sinking into the fur hood of his parka’ – but how exactly right that is, the ‘sinking’. He wasn’t actually sinking, probably in fact he’d have already sunk. But for the right conjuring, on the page, in that moment, we need the resigned, withdrawing movement to appear perpetual: ‘sinking’. Following that you write a lovely wordy, thought-y sentence, which topped off my pleasure in this paragraph as I read, because it balanced out the visceral submersion of other elements. ‘Nothing in his demeanour gave the impression of a man ready to intervene, should it be necessary.’ It had irony and an explicit intelligence in it, it was funny. All those elements arranged together on the page, the exquisite sensation of the cold water, the reluctance of the guard, the young woman’s awareness: it sounds right, it smells right, it looks right.

And what you say is true, when the vision and the words cohere in the right form on the page, it’s a powerful medicine. Tell me about how you find the endings to your stories.

Sarah:

Your thoughts about writing seem to crystallise so much of what I know I’m thinking but haven’t properly thought out! Yes, yes, yes, a seventh sense, which somehow collates all the previous ones and grants a kind of dimension to the work that’s needed to see if from behind, under, inside, outside, all at once. And thank you again for the kind words – that may be the first time I’ve been called funny! The comment made me wonder whether the ends of short stories are like a kind of gag. A reader has been waiting for something, had known it was coming, but not exactly what was coming, or how, and there’s a kind of following logic and hopefully a fitting pay-off. Like a joke – set up, engineered and elaborated upon and finished off. Perhaps that’s how it feels for a writer too in the composition. I’m hopeless at humour and so the ‘gag’ I work towards always seems like it’s going to be the complete and dreadful opposite. How I would love to end with humour! Of course there are writers like George Saunders who can keep a kind of levity and mirth amid all that is dispiriting or keep a perfect absurdity buoyant throughout, until the very end, where, boom, there may be a comedic act that utterly suits (a murdering abductor’s head not getting smashed in by a rock in the hands of the abductee’s saviour, the victim in question being more traumatized by that possibility than her almost demise). In your work too there often seems to be an enjoying quality of human observation, those very humane details about characters, about us, seen and marked and understood. Those batty, brilliant things that create individuality or likeness. I sense you must truly enjoy your characters, no matter their flaws or failings, or somehow delight in the variousness and endearing-ness of people. Is that a leap too far? And I am veering off . . .

Endings. I do feel sometimes I take the easy way out, with a kind of halted vertiginous-edge ending, or a snap-shut ending, both of which tend towards unremitting darkness and seriousness. I probably take myself and the world too seriously. But literature seems the opposite of frippery to me, even if it entertains. So often it’s about finding the right line, which has somehow caught the entire story behind it and can hold it all, have a kind of blithe gravity. I seem always to properly intuit endings and steer towards them in short stories, whereas in a novel I find myself creating false endings in my head that I use to steer around, towards another one (avoidance technique). Both aspects indicate that I don’t really plan out my fiction fully before I begin to write up an idea. Things are always made sense of along the way (I love a white page!) and an ending has to arrive naturally. Some stories are so hard to close down, but they are usually the stories that were also hard to compose and to edit, so there’s a knock-on effect of error and mismanagement earlier. Those written more fluidly from the off generally yield up an ending in a glorious, epiphanic (it seems at the time) moment. I suppose what one wants is a powerful line that summarises, or doesn’t because it can actually redirect, but isn’t overwritten or too boomy, or too latching shut for that matter. A line that satisfies the content of the story and allows the reader both release from its confines and the lasting entrapment of the story’s experience. It’s awful to say it but when writing short form I sometimes imagine a bullet wound, small precise entry point of first sentence, gaping metaphysical hole on exit. Yuck. But when a good short story finishes it has often gorgeously wounded a reader too. In ‘Then Later, His Ghost’, the story ends right on the having-to-get-back-home moment. The narrator, a teenager, has made it through tremendous storms and found what he was looking for – triumph! – but the true triumph is in getting back, isn’t it? And that feels beyond my business with the narrator, in a way. I suppose it’s post-coital triumph too, in the erotic stories, the triumph of being a successful human and relating to other humans, not just a rutting hungry animal, and stories often leave a reader at that moment when acts have occurred and characters have reacted, but the reader is then asked to imagine the fuller picture, to contemplate our nature, our flaws, our possibilities, existence, meaning. I love that wonderful invitation. Short stories are marvellous devices that way, like mind and self puzzles. Where do we go from this point at which we are challenged? Where do you go? The trick is maybe about what question is finally posed. That seems to suggest there’s a thematic or greater idea behind everything written – it is, of course, and as you suggested earlier, also about the right moment to leave the story’s actual proceedings, the logic of chronology and choreography, the place of dramatic conclusion (even if there is anti-drama), peaks, falls, tensions, releases. Simply the right moment/thought/word/act.

Tessa:

Characters first. Yes, only fiction has this opportunity to be inside and outside character at once. In films and plays and paintings we can watch character from outside – which is of course how we experience it in life, in other people. I love that sustained slow attention fiction can give to individual characters, trying to render in words everything from their physical presence to their aura, their manner, their effects on others – and then if required, miraculously, also their introspection and self-consciousness. It’s no wonder we quail at the responsibility of writing fiction. (I’ve just had a bad writing day, full of doubt.) One of the great things about the novel form is that in its sheer length it has room to convey how multiple and contradictory one ‘character’ can be. Characters in short stories have perhaps (but not always – Munro and Gallant, for instance) to be more condensed, and self-consistent. As for liking the people one invents – there’s a sweet spot, isn’t there, between being too blandly nice about one’s fictional people, and too snugly disparaging. There should always be plenty of bite in their treatment, and a sort of generous consent as well.

And endings. A tag line for a joke, or the exit wound from a bullet – both are marvellous descriptions. Also the post-coital moment! Once upon a time stories had more of a conclusive tag line, I suppose: in Kipling, or Saki. The reader wanted a twist, a revelation, an exhibition of ingenuity. Now those ingenious endings tend to sound old-fashioned. We don’t have faith in the kind of knowingness Kipling exhibits so superbly in Plain Tales from the Hills – which fastens things up finally, and ‘gets’ them. Chekhov taught the short story its radical doubt, its side-step-ending. Endings, nonetheless, are still crucial to reading a short story. As we read it, we hold all the accumulating content in suspension in our thoughts, waiting to know what it adds up to – which we find out, when it stops. There, now we have the whole thing. It rearranges itself retrospectively in our awareness, now that we know how it ends. You couldn’t possibly sustain that ‘holding in suspension’ to novel length. The endings of novels in some ways are less important. The whole implication of the novel doesn’t depend on them, as it does in a story.

I think your ‘line that satisfies the content of the story’ might be the key. Although the content of a story is so small beside the chaos of life itself, nonetheless we should feel at its end that we’ve seen everything we’ve needed to. The last lines step away from the content: and somehow in the light its ending sheds back on the rest, however modestly or inconclusively, the story feels completed. Even if the ending puzzles us, it should send us back inside the words of the story we have, searching for clues – not make us feel something’s missing.

As for being funny, being serious . . . I think temperament – which sounds like another very old-fashioned idea – is fundamental to writing style, determines it to some extent. Character (the writer’s character) really is fate, for a writer. You can’t fake the shape and colour of your mind, as it expresses itself in words. You develop your style to express the real texture of your perceptions. That’s what I did, as best I could. I wrote fake books at first (never published thank goodness, quite awful), trying to be someone else, and then realised I had to find plain ways to say what I really perceived. Of course once that door of style is opened, then you can step through it into wonderful places. It isn’t simply ‘write what you know’; or rather, it’s amazing what you can know. But you can only only write who you are.

Photographs © Mark Vessey and Nadav Kander

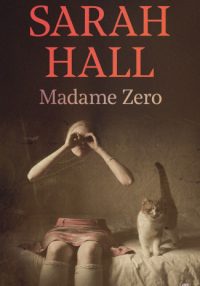

Sarah Hall’s most recent collection Madame Zero, was published by Faber & Faber this year.