Brunström would sometimes talk about the great break-up of the ice. He’d say that if you haven’t seen that, you haven’t seen anything, and I’m not talking now about the ice breaking up in one of those little bays deep in the archipelago.

Tooti and I decided we had to be there for a real break-up, but it was several years before we could get away. It was in March – late winter, early spring.

We rented a hydrocopter built by Valter Liljeberg in Pellinge, made of thin planking reinforced with fibreglass. The motor was a Chrysler. At the stern, the hydrocopter had an airplane propeller protected from the passengers by the flat springs of a folding metal bed, a Heteka. We were allowed to bring a backpack, and we sat with our knees drawn up. The engine started with a roar and the whole rig moved out across the ice at a furious pace until suddenly the hydrocopter broke through, sank to its railings and started to wheeze. Then it crept forwards very slowly, crawled back up onto the ice and zoomed off again. We went on like that, on the ice and off, all the way to the boat channel, which was packed with floes. The captain climbed out and gave the nearest block of ice a kick, then hopped quickly back on board, the hydrocopter turned its nose in a different direction, took a detour and then everything went fine. We flew like the wind the last kilometre across glassy ice, dark and transparent, skating over the shallows where the brown seaweed forest undulated beneath us.

We arrived at the island and the hydrocopter went back home.

The cabin had that closed-in chill that Brunström would have called ‘cold as a wolf’s parlour’, and someone had burned all the firewood. We found a couple of wooden crates in the cellar and got them to burn and dragged in the sawhorse and some ice-covered timbers to thaw.

We were exhilarated by change and expectation and ran headlong here and there in the snow and threw snowballs at the navigation marker. Tooti made a toboggan out of thin strips of wood, and we rode it again and again from the top of the island far out across the ice.

When we tired of that game, we sat down and took stock. The sea was chalk white in every direction as far as the eye could see. It was only then that we noticed the absolute silence.

And that we had started whispering.

Now came the long wait. I was seized by a new feeling of detachment that was utterly unlike isolation, merely a sense of being an outsider, with no worry or guilt about anything at all. I don’t know how it happened, but life became very simple and I just let myself be happy.

Tooti cut a hole in the ice for our garbage.

We grew quieter and quieter and went about our daily chores as if we’d each been there alone. It felt very relaxed.

And one night it happened, but very far out to sea, probably with no one to see it. It sounded like distant thunder or maybe like artillery. We ran up to the top of the island, but the sea ice looked exactly the same in every direction. We waited a long time, freezing cold, but nothing happened, so we built up the fire in the stove and went back to bed.

Failing to wait when what you’re waiting for is your own majestic goal, that’s just unforgivable.

What was I thinking that time at Vesuvius? I’d really like to know. I mean, there he was, acting up a bit, and I was there! I was nineteen years old, and I’d waited all my life to see a mountain spitting fire. The moon was out, fireflies too; the earth was aglow – and what did I do? I dutifully took the tourist bus back to the hotel in order to drink my tea and go to bed! Who takes the time to sleep when a thing is finally happening? I could have stayed there all night and had Vesuvius all to myself.

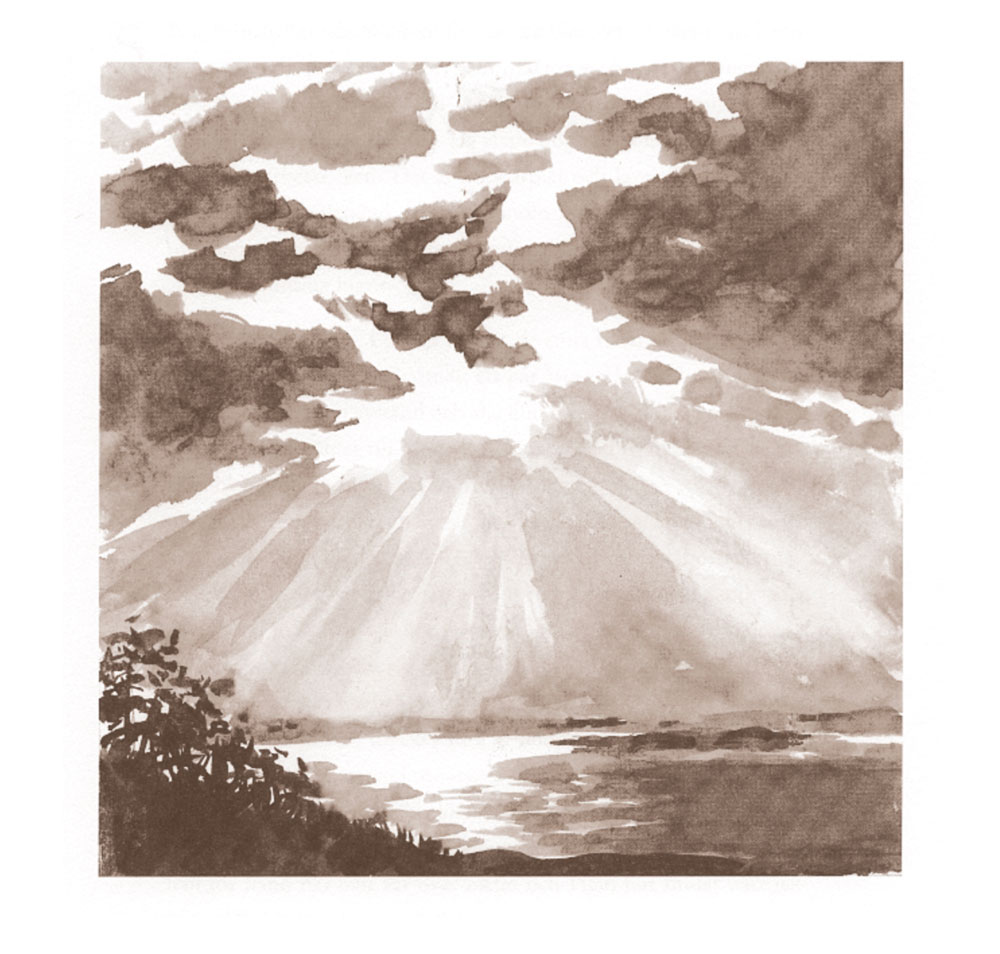

In any case, we overslept. When we woke up, the whole ocean was full of broken ice. Unbelievable tabernacles floated by, driven by a mild south-west breeze, statuesque, glittering, as big as trolleys, cathedrals, primeval caverns, everything imaginable! And they changed colour whenever they felt like it – ice blue, green and, in the evenings, orange. Early in the morning they could be pink.

It started to blow and the floes piled into each other, rearing up, thrusting down (as if having an orgy, as Brunström might have put it).

They changed shape continually and fantastically on the way to their ultimate transformation into water.

The lagoon didn’t budge, frozen all the way to the bottom, its inlet full of still untouched snow between black rocks.

Tooti said something about how it’s all very well to go all technicolor nineteen times a day, but the purest and most honourable colours are still black and white.

Artwork © Tuulikki Pietilä 1996

This is an excerpt from Notes from an Island, available from Sort Of Books.