This is what I picture: the photographer, Corinne May Botz, dipping her head under the black hood of her camera to look through the lens, her hair slipping over her shoulders. The photo she is taking is of an open doorway in an old house. It’s possible to see through to the next room, and then another beyond it: the gaze settles on an out-of-focus wall with exposed woodwork, where pale wallpaper is peeling. The focus of the image, though, is the doorway itself. It invites us in. We linger, like Botz does, at the threshold.

The photograph itself features no silhouettes on walls, no reflections in mirrors, no footprints on floors. There is no evidence that Botz was there at all. ‘I wanted,’ she tells me later, ‘to open myself up to the invisible nuances of a space.’ To act as a kind of medium for each house, a mouthpiece; allowing each room to speak. This photograph of a doorway, alongside eighty-four others, appears in a project Botz called Haunted Houses – a series of images capturing rooms in different buildings across the United States. Botz visited over one hundred of these houses, on and off, for ten years.

Corinne is sitting in her office in Catskill, New York when we first speak on Zoom. There’s a blank wall behind her, a similar magnolia colour palette, I think, to the photograph of the doorway. She speaks fast, beginning her sentences multiple times to find the correct phrase. She seems anxious to get to know me. Our internet connection has a delay, so we speak over each other sometimes. A few minutes into the conversation, I ask her if I can start recording. To my surprise, she says no, telling me that she would rather talk first and be interviewed another time. I tell her I don’t mind, but secretly I agonise over what we say to each other, imagining each word disintegrating as we speak. It’s an anxiety I know from journalism – the sinking feeling of noticing the tape recorder’s static numbers, or replaying a jumbled phone recording – the acute dread of losing good sentences. I try to talk without worrying, wondering if what we say can be captured on our next call when Corinne knows I’m recording. I scribble pieces of our conversation in my notebook to return to later, a frantic attempt at preserving, and they become a strange list: ghost stories, Shirley Jackson, stereo cards.

Private Residence, Hawthorne, NJ

After she graduated from Maryland Institute, College of Art with a BFA in photography, Corinne spent the summer living in an old apartment in Baltimore. It was 1999. She spent long, hot days browsing the local library for ghost stories and haunted house fiction, stacking Toni Morrison, Edith Wharton and Charlotte Brontë novels on her desk. They spoke to her existing, private beliefs: that domestic space could harbour strange atmospheres; that women were uniquely receptive to these atmospheres, as if hearing a low, constant song. ‘I definitely feel very attuned to spaces, I always have,’ Corinne tells me on our second call – one I record, this time – a few weeks later. ‘I think houses can collect histories and memories.’ She grew up in New Jersey, but spent a lot of time at the cabin her parents owned in an isolated part of the Catskill Mountains, a rural part of upstate New York, with no electricity or running water. One day, her parents returned home with a stereo viewer – an object that looks a little like a pair of binoculars and displays two separate photographs as a single, three-dimensional image (they were, I read later, used as home entertainment from the 1850s to the 1930s). Corinne, already developing a taste for the macabre, spent hours with it, poring over stereo cards – her favourites were those depicting ghosts and funerals. It was at her childhood home in New Jersey, in the bedroom she and her sister shared as young children, that she remembers once seeing ghosts – gliding in clusters, wearing thin dresses, rummaging through her possessions. She lay still, wishing that she were invisible, that they would not notice her looking. ‘I felt like I couldn’t move or tell anyone about it,’ she says. It was a moment that stayed with her: the experience of bearing witness to something strange, alone. A private, ambiguous magic.

I know, while we are talking, that Corinne is waiting for me to ask her about The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death, which she began in 1997. The project lasted seven years, and garnered her significant critical attention: the photos were published by The Monacelli Press in 2004, and were included in exhibitions across the US and Europe, including the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago, Illinois, and Württembergischer Kunstverein in Stuttgart, Germany. The exhibitions earned reviews in New York magazine, The Village Voice and The Boston Globe, and Corinne was later profiled by the New York Times. It unexpectedly became her most successful project, as well as her most financially lucrative. Even now, it’s the work people most want to talk to her about – and it began with a chance conversation. Still studying as an undergraduate, Corinne was working on a film about female doll’s house collectors. While shooting, one of the women mentioned Frances Glessner Lee, a criminologist who made miniature models of crime scenes used to train detectives in the 1940s and 1950s. The models, called ‘Nutshells’, were housed at the Baltimore Medical Examiner’s Office – just across town from Corinne’s college.

Atlas Theater, Cheyenne, WY

It’s easy to see why the Nutshells are so compelling – not only through the lens of Corinne’s camera, but of their own accord, as objects. Each three-dimensional scene is intricately detailed, depicting various causes of death – an open gas oven, rope suspended from the ceiling. They invite speculation: who do the bloody footprints on the carpet belong to? Does the knocked-over furniture indicate a struggle? Most of the victims in these scenes are women: dolls stretched out on blood-stained bed sheets, lying on tiled floors, collapsed in bathtubs. Corinne saw them for the first time on her twentieth birthday. She was captivated – the models were an impossibly perfect meeting point of her interests in evidence, gender and space. She decided to return with her camera – a large format model, the type that is immediately obtrusive: it stands tall on a tripod, a thick concertina of bellows connecting the lens to the film pane. It remains her camera of choice twenty-five years later. ‘People often think of this camera as cumbersome,’ Corinne explains, ‘and I guess it is in certain ways, but I’ve been using it for so long it’s really second nature for me.’ The camera was instrumental in shaping the Nutshell photographs: the film – four-by-five-inch in size – is extremely high quality, but expensive; it made her, as a result, very particular about the photos she took. It gave her a ‘meditative way of working’ – and the Nutshells themselves invite this way of looking. As models, Corinne tells me, they were never designed to be ‘whodunnit exercises’, but to teach detectives to ‘observe and evaluate indirect evidence’. More than anything else, the Nutshells are, then, an exercise in seeing – in paying attention to the language of a room. The way a room – the angle of a chair, maybe, or a scratch by the door frame – holds evidence of what has happened there. The models would become her subject of obsession for the next seven years.

The rooms in Corinne’s Nutshell photographs are frequently mistaken for real crime scenes. It’s something to do with their scale, with their angles: it isn’t immediately obvious that we are looking at a doll’s house. When I first viewed one scene – a knocked-over chair in a bedroom, a dresser, blood on the carpet – I believed I was looking at a real room. It was disorientating. In a gallery setting, assessing the true scale is even more complex: the physical photographs themselves are huge; they swallow the gaze, distort proportion. Failure to understand the photographs at first glance is part of their appeal: this failure creates the compulsion to keep looking. It was deliberate, Corinne tells me, to shoot the models this way: there is no distance. Instead, the viewer is enveloped fully by the rooms, faced with an almost claustrophobic intimacy. It’s this gaze – intimate, obsessive, sustained – that forms the heart of Corinne’s work. When we talk, it’s obvious that the Nutshells were a deeply formative project – she describes them at one point as a gift – but she acknowledges, too, that she has grown a little tired of talking about them. She sends me an email later, worrying that she overemphasised the point. ‘I always say that I went to two undergrad schools – Maryland Institute College of Art and the Baltimore Medical Examiner’s Office – and they both taught me how to see.’

After her undergraduate degree, Corinne began something new: she decided to visit and photograph haunted houses. From the beginning it felt like a private endeavour: she was selective about who she shared the images with, feeling protective of them – as if vocalising their magic too early might cause it to fade. Like much of Corinne’s work, this was the product of slow, enduring focus. She first began taking the photos after graduation, but would not publish them for another decade. They accumulated, gradually, alongside other work.

For her thesis a few years later − in 2006, she began an MFA at Milton Avery School of the Arts at Bard College in New York − she began work on another project, titled Parameters. Houses were, again, her subject: she took photos of the homes of people with agoraphobia – a condition which, she tells me, affects more women than men, and is described as a phobia of public places from which escape may be difficult. Those suffering with agoraphobia tend to stay in their homes; it is a space they can control, but one they cannot leave. The images in Parameters are intimate, a tense exchange between haven and prison: plants in macramé hangers obscure the pale glow from closed blinds; a table is covered with completed jigsaw puzzles; a calendar is pinned to the wall, with a cross scratched through every passing day. Each photo is eerie, uncomfortable somehow. I feel, looking at them, as if I’m trespassing, a witness to private coping mechanisms. The rooms are bathed in fear – sometimes palpable, sometimes muted. The photos are, like the Nutshells, mesmerising.

And then there it was, from nowhere: a coincidence. An unexpected echo. Corinne visited the homes of thirteen women with agoraphobia, and many of them, she tells me, had ghosts in their houses. This is the way she phrases it to me – had ghosts in their houses – without passing judgement. I wonder if, standing in those women’s rooms, she remembered the ghosts in her childhood home in New Jersey, if she felt some vague pull to them in that moment. I wonder if, standing in these rooms, it seemed like a sign, pointing her gaze back to Haunted Houses. As if the work itself were a question she did not have the answer to, she returned to it, she tells me, more seriously from that point onwards – to ‘resolve it’.

Abandoned House, Frankfort, ME

‘I would just show up at someone’s house with my camera and knock on the door, and say: I heard you have a ghost story, can I come in and take a picture?’ Corinne told an audience during a 2019 lecture at the School of Visual Arts in New York. She rarely planned her locations in advance and travelled spontaneously to different towns across the US, talking to local residents at libraries, diners and cafés, listening for haunted house tales. After gaining permission to take a photo, she would step into the house, and wait for a room to reveal itself to her. It was an old practice, a method she had learned with Nutshells and Parameters, and it was heightened by the four-by-five large format camera. It was a slow process, but an unexpectedly generative one. ‘If I had been photographing digitally, I never would have finished that project,’ Corinne tells me. ‘If you shoot digitally, you end up taking a lot and seeing what sticks. You take more pictures. But with the four-by-five, I would only take a few.’ It made her, she believes, a better photographer. ‘When I listened to, say, some weird detail – just what drew me – and when I followed my own subjectivity and inner voice as an artist, that’s when I took the best pictures.’

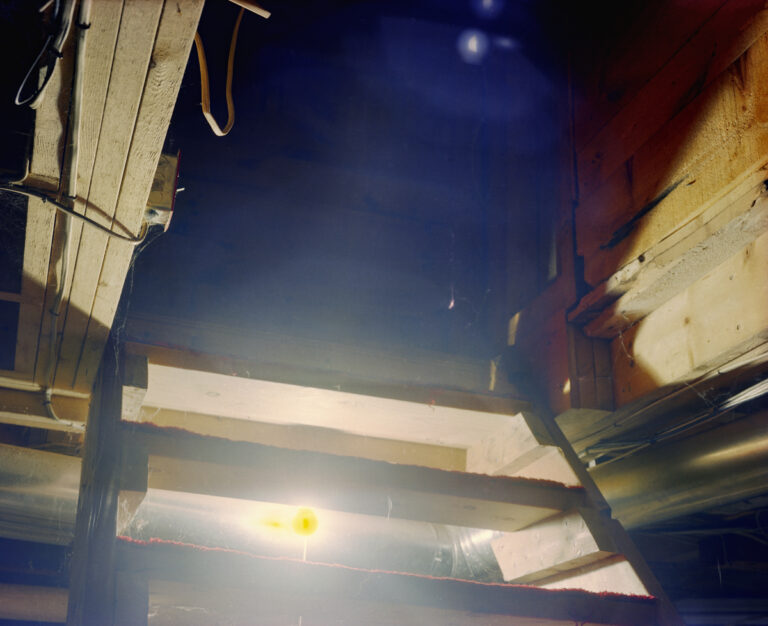

Corinne visited over one hundred buildings across America, and the photos that comprise Haunted Houses are threaded with the ‘weird detail’ Corinne tells me she was guided by. We see kitchens, hallways, dining rooms, attics, bedrooms; she takes photographs in houses, apartments, prisons, hostels, cabins and farmhouses. Some spaces are more visibly strange than others. In one, Corinne’s camera is angled upwards, looking at the wooden stairs into an attic space, the light from a naked bulb blocking our view. The space at the top of the stairs is a dark void. In another, a door is propped open with a black stone, light pouring onto the landing carpet. On first look, there seems to be nothing unusual. It’s a recurring theme throughout the photographs: many of them bear the markings of the deeply familiar. There are children’s toys, lamps, floral bedding, laundry. This approach, however, was met with mixed reactions.

Private Residence, Harlan, KY

One reader of the book, on Goodreads, complains that the photography is ‘a little bit odd. I didn’t really get why there were random pictures of rooms. Even though they may have been haunted, most of them didn’t seem particularly scary or menacing.’ He isn’t wrong; most of the photos are not particularly scary or menacing, at least in the traditional sense. But this is what makes them so remarkable: they reject sensationalist narratives of hauntings in favour of something else – a quiet sense of unease. They ground us in ordinary domesticity – its pleasures, its disturbances.

As well as the large format camera, Corinne also brought a tape recorder with her, planning to record the ghost stories people told her while she travelled. Most people she met were eager to share their experiences; she was often invited to stay for dinner. ‘I stayed at someone’s house in Harlan, Kentucky, instead of my hotel for the night,’ she told the audience at the School of Visual Arts. ‘People really opened their houses up to me.’ Some of the stories she heard were unnerving: Dom and Louise, a couple living in Maine, reported hearing strange noises – a musical chime in the early hours of the morning; the low murmur of the television being switched on while they were asleep; the sound of a chair dragged across the floor – only to discover that no furniture was moved downstairs. They began recording each incident, writing events on scraps of paper – as if to prove, perhaps, that it happened. Heidi, a tenant in a house in upstate New York, remembered feeling ‘something like light footsteps’ move across her bed at three in the morning. The next day, Heidi’s roommate told her she dreamt about a ‘presence’ in her own room – at the exact same time. There are similar sensory experiences across all the stories: people report hearing music, feeling a hand touch their shoulder, smelling strange perfume on the landing, seeing figures move out of the corner of their eye. Many stories take the tone of confession – as if the speakers were relieved, finally, to have someone to share them with.

Many people complained of being afraid on their first encounter, but as time passed they began to see the ghost as a feature of the house – a benign part of the architecture. ‘Hollywood has us all believing that ghosts are almost like ghouls and something to be afraid of,’ Nancy-Linn, a former resident and innkeeper in Searsport, Maine, said. ‘Our spirits seem to appreciate that I always acknowledged their existence, and we have all learned to live together in harmony.’ While visiting a house in New York, Corinne met a woman called Denise, who confessed, ‘None of it ever felt uncomfortable or unsettling: it was more of a comfort. It was like caretakers in the house.’ Across the stories collected in the book, ghosts watch over residents, close doors, wake families up when there is a fire. One woman claimed that if her house were being burgled, she believed her ghost would scare intruders away. Many of the people Corinne spoke to took pleasure in their ghosts; they were a source of protection. Her photographs reflect this: there is a domestic gentleness to them. They are meditative, soothing almost – an assortment of messily made beds and warm afternoon light streaming through curtains. Ghost stories, then, are not always characterised by fear. Sometimes, they are stories of belief, comfort, faith.

Most of the stories Corinne recorded are mild, tame, and there is, I’m sure, a way to see this project as a failure – a failure to adequately capture hauntings on camera; a failure to summon what we expect from ghost stories. But this failure is part of the work’s texture. There is, Corinne notes in her introduction to the book, an inherent ambiguity to photography, and the stories and images she collects are incomplete – this imperfection points to ‘the failure for either words or images to properly elucidate the world’. Perhaps this was what made certain readers so frustrated: the failure of the photos to render visible what is hidden. Titling her project Haunted Houses prompts us to begin searching for what is missing. We grapple with the lack of evidence while we’re looking for it; the absence fuels our gaze.

Private Residence, Clinton, ME

While Corinne and I speak, I flick through the photographs in the book. Some of them I find – for reasons I’m unable to properly explain – strangely unpleasant to look at. There’s an almost unbearable sadness to the photograph of the toy car on a frayed magnolia carpet. The light as it settles on a sofa makes the room seem lonely, somehow, as if an unhappy conversation has happened there moments before. It’s like certain rooms – even through a page – carry traces of something I can’t quite decipher, something I recoil from, like a contaminant. I realise, of course, that it’s my own projection, my own speculation. It’s exactly what Corinne is inviting, but knowing this doesn’t erase what I see. It can’t remove my filter. It’s my own subjectivity edging, bleakly, into view. It coats each photo with a gloss only I can see.

Our conversation on domestic space turns, eventually, to the place I expect it to. At one point, Corinne pauses. ‘Without sounding too new agey or something, I do think energy doesn’t disappear,’ Corinne tells me carefully. ‘You have physical traces of histories and environments, and spaces just have different feelings to them. There are some places that just don’t feel very good, and others that do – at least in my experience.’ We start to talk about these energies – the energy left by previous residents; the knowledge of a violent event that took place in a room; the materialisation of a ghost – and the ways that domestic spaces collect impressions.

I wonder if Corinne’s slightly tentative response – without sounding too new agey – is meant to draw me in, to invite me to share with her my own experiences of domestic space. She tells me, at the beginning of our call, that she has read a few of my essays online; I can’t help but wonder if she has read about the house I lived in with my father, if she knows already. I wonder if speaking it aloud – making it explicit – would be pointless. But it filters into the conversation regardless: I tell her that this sensitivity to space is something we both share. I linger here, at the threshold, uncertain whether to say more. She waits. The silence lingers and there’s a crackle through the connection.

Moments pass on the call. I want to tell Corinne how I came to know that houses can harbour strange atmospheres. I want to tell her that my own sensitivity to space was developed by way of necessity and became a habit I have not been able to shake since. I want to tell her that I stayed as still as possible in the rooms I grew up in to record, with striking accuracy, the emotional weather of a room. It’s strange, I want to say to Corinne, to see this sensitivity in translation: to sift through a series of photos in which attention is paid to a single object in a room, a nail on a floorboard, a scratch on a wall. It feels like my gaze – an old gaze, but one I carry with me, like a spare lens – is replicated across these pages.

These things are on the tip of my tongue. I wait. Corinne waits. I think about telling her these things, but I don’t. I don’t know if it’s really that relevant. But as soon as I have the thought – I don’t know if it’s relevant – I turn against myself. Of course it is. It taught me how to see. It’s why, I think, I can’t look away from Corinne’s photos; why I find them so unpleasant and so mesmerising. They invite me back to that way of seeing. To the sensitivity required to read a room.

Basement, Londonderry, NH

In the novels Corinne was reading the summer after her graduation in Baltimore, receptivity to the otherworldly was, most often, the domain of women. It’s a familiar convention of Victorian gothic literature: women were often the characters who sensed the presence of ghosts; the majority of mediums, too, were women – their ‘emotional sensitivity’, Corinne tells me, was cited as the reason they were able to communicate with the dead. Women are, often, at the centre of the stories Corinne collected on her journeys: many people report seeing female ghosts – sometimes mothers and daughters, sometimes domestic workers doing dishes or mopping floors; women are also often the ones to discover supernatural presences in the house. In Somerset Hills, New Jersey, a woman named Bernice was told about her ghosts by her house sitter: ‘When we came home the lovely girl who was watching the animals and taking care of the house said, ‘Do you know that you have ghosts in this house?’ And I said, ‘Really? How can you tell?’ and she said, ‘There was so much conversation on the third floor. Voices, voices, voices, voices.’ I said, ‘Weren’t you scared?’ And she said, ‘No. There were just all of these voices talking on the third floor. I went up there, and I couldn’t see anything, but I could hear them talking.’’

When Corinne stepped into each house, it was this receptivity she found herself thinking about – how to tap into this sensitivity to produce an image. ‘I tried to open myself up to the invisible nuances of a space,’ she writes in the introduction to the book. ‘I listened and attempted to be at its mercy.’ In Corinne’s writing on her journeys across America, there is this strikingly rich language of openness, sensitivity, receptivity, submission. I attempted to be at its mercy. It’s a language of surrender. There’s a tendency to describe submission – especially in women – in terms of deficit, weakness, defect. As if we should all aspire to dominance or control. But what if it could be a source of power, this sensitivity to an unknown voice, a presence, a room? What if you could be a receptacle for something larger than yourself? What if this sensitivity was a gift?

Vealtown Tavern, Bernardsville, NJ

A few months later, when I set out to transcribe our second conversation, I try some new software a friend recommends. It transcribes the interview with a few glitches – dips in the internet connection, mispronunciations of words. It splits up Corinne’s speech into separate lines, as if she were different people speaking. Each line carries a time stamp. Each one is labelled Unknown Speaker. As I listen back to the conversation, I flick through the pages of Corinne’s book. The open doorway. The toy car on the carpet. The scratches on the floor. I think about these rooms. The surrender required to tune into their frequency.

I wonder how Corinne felt, sitting in these houses, hearing these stories. I was surprised, reading them, by how many people express a level of scepticism about their own experiences – even as they are telling them to be recorded. Some choose their own rationale, writing off certain explanations in favour of others – everything from dreams to old architecture to faith. Many tell their stories without attempting to frame their experience with any rational explanation. But buried in all of these accounts is the idea that some things are unknowable to us; some realms of experience resist easy explanation.

I’m curious to know if Corinne believes the stories she heard. ‘I always feel like I have to make it really clear that I’m not proving or disproving anything,’ she tells me. She’s speaking slowly, careful to get the words right. ‘I’ve always been uninterested in tidy resolutions.’ This is, I think, the heart of these photographs: in the absence of resolution, there is something open-hearted, gentle, searching. ‘There are my super subjective photographs. Then there are these very personal stories that are told. And then the third subjectivity is the viewer and what they bring to it,’ Corinne tells me. ‘But also I think there’s a sense that every time we look at artwork, there’s this projection that takes place. How much are you actually seeing? And how much are you just projecting?’

All images © Corinne May Botz