On the hills of Brescia, overlooking Lake Garda, stands Vittoriale degli Italiani (The Shrine of Italian Victories), the estate of Gabriele D’Annunzio, a poet, novelist, warmonger, lothario and bloodthirsty rhetoricist born in 1863.

Gabriele D’Annunzio’s determination to be famous started early. At the age of thirteen, he wrote that his two aims in life were ‘to teach the people to love their country,’ and to ‘hate the enemies of Italy to the death’. Shortly after he had his first poetry collection published at sixteen, he spread rumours that he had died. The collection, seen to be by a poet lost tragically young, took on new significance. This was his first taste of fame, but it was certainly not the last. Unconcerned by the drama he caused, he reappeared. D’Annunzio had no empathy, no sense of repercussion. In life, he played.

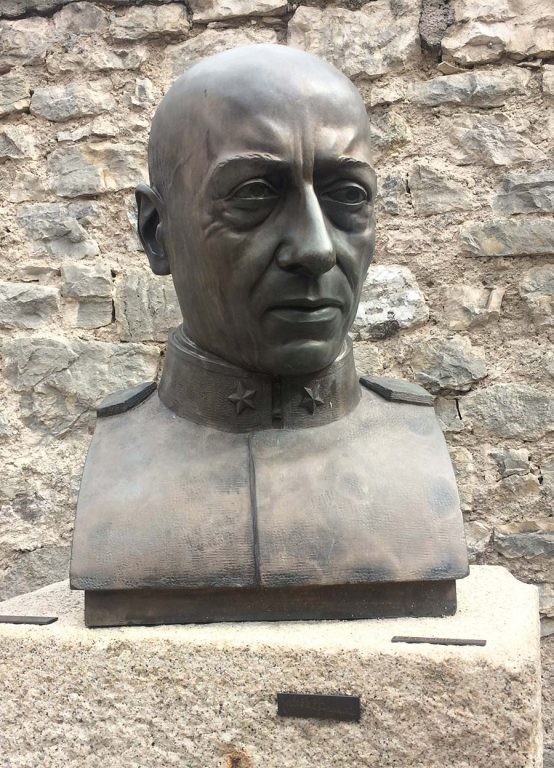

He was an awkward-looking man – shorter than five foot four, balding at a young age, and always wearing his glass eye after the war – and yet people were drawn to him. He cultivated an eccentric, aristocratic identity. He dressed impeccably and rehearsed the witticisms and postures he would perform to crowds, and before the duchesses and actresses he courted. His children, following his instruction, addressed him as ‘maestro’. Benito Mussolini described him as ‘the most Italian of hearts’. It was not just his character that seduced – for others, it was his work. Henry James and Marcel Proust praised his writing; James Joyce believed he was a ‘magnificent poet’.

When the First World War struck, D’Annunzio was fascinated by the conflict. His rhetoric grew louder. He was publishing frequently – not just poetry but novels, tragedies, short fictions. He was no longer just drawing women to his bedroom, now he was sending children to the battlefields. In speeches he demanded that children must be sacrificed. ‘We have no other value’, he raged, ‘but that of our blood to be shed’. The public obliged. He was a magician – a twisted Pied Piper. In September 1919 he took over Fiume (now Rijeka in Croatia), arriving with two thousand nationalists and occupying the city for fifteen months. Settling in as dictator, there he created the rituals that would become fascism: the saluting; the extravagant addresses made from balconies; the war cry he encouraged in response, ‘Eia, eia, eia! Alala!’, borrowed from the Homeric epics. D’Annunzio established a performance of power; he tested and perfected the manipulation of a crowd through words. He is disturbingly pertinent still – a monumental example of how a man’s insistence can be enough to achieve anything.

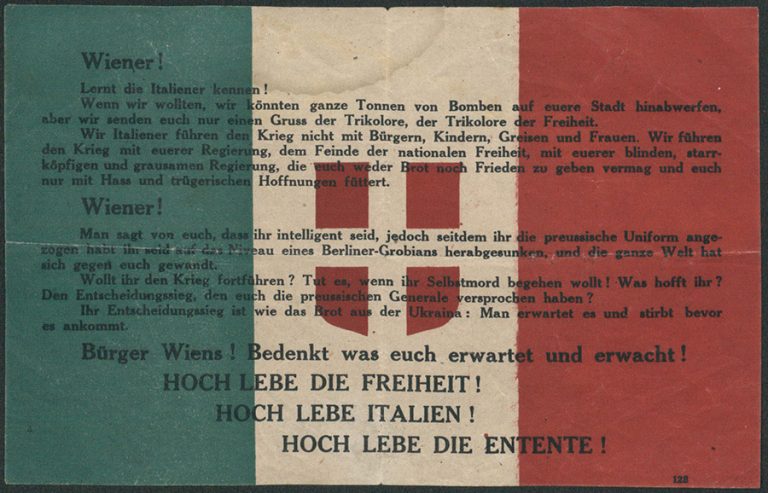

In The Pike, Lucy Hughes-Hallett’s expansive, Samuel Johnson prize-winning biography of D’Annunzio, she writes: war brought him peace. What would scare others intoxicated D’Annunzio. The First World War was revelatory. The excitement! The bloodshed! The regime! The war was his stage. He stopped a bomb from going off with his bare hands. He led a 700-mile round trip to Vienna in a fleet of planes – a mission seen as suicidal. But he succeeded. In an act of gratuitous power-play, he dropped propaganda from planes over enemy lines, calling for civilians to awake and proclaim the good of Italy. How easily, he showed, could those packages have been bombs. It was the perfect combination for D’Annunzio – exercising his love of risk in stylised performance.

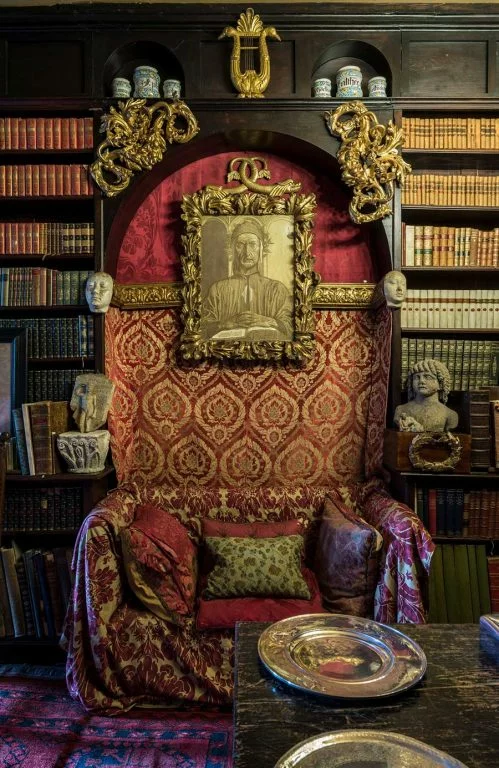

Everything remained a performance. Gabriele D’Annunzio would never condone being ordinary. He was obsessed with overstatement, with grandeur. The Vittoriale, where D’Annunzio resided for the last twenty years of his life, less stands in the hills than sprawls. It is immense: consisting of numerous villas for himself, his children and his lovers; labyrinthine paths; lakes; an amphitheatre; a mausoleum and an auditorium with a plane suspended from the ceiling. The Vittoriale is closer in appearance to an antiquated theme park than the home of an aging writer.

It was only as I began to traverse more of the grounds that I noticed irregularities – hints of D’Annunzio’s persona. Large artillery shells framed the sides of paths. Statues of naked women broke up the gardens. For D’Annunzio, character comes through the detail. In the years he resided at the Vittoriale he never stopped expanding it, embellishing it and isolating himself.

The entrance to the Priory, the main building where D’Annunzio lived, is sharp-lined – painted yellow with white columns and a flat roof. The facade is covered with fading coats of arms and shields, like a teenager’s jacket, over-adorned, badges extending far beyond the lapels. The wooden front door is framed by a stone arch. It could be a chapel. But this serenity was disrupted as the tour guide ushered me into the entrance hall of the house and shut the door. Suddenly we were in darkness. Deep brown wood lined the walls and ceiling, red carpet folded over sharp steps that led up to a stone column. Two entrances were ahead. On the left, the Waiting Room for Welcome Guests. On the right, for the Unwelcome. Mussolini, I learned, was always directed to the right.

Picture frames cover walls. Vases crowd tables. Rugs cover carpets. Walls are indented with hollows, display space for yet more trinkets. Murano glass is set into windows and makes up chandeliers and pomegranates. Pomegranates – a symbol of profusion – are spread, real and fake, around the house. The estate’s grandeur is not in its large windows or broad doorways, nor the sweeping staircases, but in the way D’Annunzio compacted and added and filled every available space. Everything is intricate and overwhelming. It’s unclear what to focus on as you enter each room. There is too much.

With the spark of Fascism set in the early 1920s, D’Annunzio retracted into the still hills of his estate. He was stagnant. His body deteriorated. He was quietly, slowly dying. His lovers persisted, ever-renewing and overlapping, among them servants and heiresses. For the last four years of his life, one of his lovers was, unbeknownst to him, a Nazi agent keeping him under close surveillance. Mussolini looked on as well. D’Annunzio only exaggerated his own strange entrapment. The house – in darkness, with gridded ceilings and low, thin spaces – reeks of captivity. Looking out the narrow strip window of the veranda, the light feels intrusive, the conversation of a few tourists in the square invasive.

Many items in the house are useless; meant only to impress, not to be engaged with. Though D’Annunzio was one of the first in Italy to own a telephone, it sat in an alcove, rarely used. There was no one else for him to call. His private bathroom contains 900 objects, including ten silver hairbrushes. D’Annunzio had no hair, but the brushes are there, just like much else in the house, for their beauty, and that alone.

Above the door of another room reads the words: Five are the fingers, and five are the sins. This was D’Annunzio’s mantra. He disagreed with the idea of seven deadly sins, for you only have five fingers, and thus the number of sins must surely correspond. Although not a strong logic, it was certainly a helpful one. It allowed him to erase two of his key pursuits from the list: greed and lust.

The man who prototyped fascism, who tested, in deep apathy, what effects could be provoked by power and fame, grew weak. The speeches stopped, but the writing continued. At seventy-four he died of a brain haemorrhage, after twenty years at the Vittoriale, time enough to rest, to extend his already extravagant home, to walk, to read, to debauch, but not, it seems, to regret.

Images © Marco Beck Peccoz