At first, Enoki was utterly confused.

It started suddenly. Without any forewarning or explanation, people suddenly began visiting. They came in droves to find her. Initially, Enoki had no idea what they had come for. When she finally understood, she was flabbergasted.

Yes, she was aware that there was something a little unusual about her body. Specifically, she had two largish burrs on the lower section of her trunk. But she thought nothing of it. Everything and everyone has an idiosyncrasy or two, including hackberries like herself. It’s hardly anything to marvel at. Nowadays, people term it ‘individuality’. In any case, the lumps were no big deal to Enoki, and she didn’t give them much thought. Burrs were just burrs.

And yet, people said that Enoki was special. People took her knobbly, rounded outgrowths for something extraordinary. They stood in front of them and prayed, and carried off the resin oozing out of them.

What on earth was going on? Their behaviour bewildered Enoki. It seemed to her a kind of madness.

The women were particularly strange. Watching all these desperate women as they joined their hands in prayer and bowed their heads to her, Enoki felt like she was missing a trick. It was something she never truly got used to, but at the beginning, when she was particularly not used to it, she would feel the rage bubbling up inside her. What the hell are you people playing at?

When it first occurred to Enoki that people saw her burrs as breasts and her resin as milk, she shuddered. Even now, when she recollects that day, there is only one word to describe her feeling, and that word is disgust.

Allegedly, the ‘sweet dew’ that was Enoki’s resin had special properties. If mothers with trouble lactating rubbed the resin on their breasts, they would start producing milk. Give me a break!

Allegedly, Enoki’s ‘sweet dew’ was no different from human breast milk, so if the rubbing proved fruitless, you could feed the resin directly to your babies and they would grow up healthy and strong. Give me a break, guys!

Every time she heard people around her in the shrine grounds spouting this crazy nonsense, Enoki would shout the same thing in her mind, flapping her leaves in frantic resistance, but nobody noticed. Everyone was so obsessed by her burrs and her resin, they had no time for anything else.

People loved to see things in other things. Enoki knew that very well. You could even say that this was the starting point for all religion, and moreover, that it wasn’t always a bad thing. But when people saw the burrs on her body as human breasts, Enoki felt a strong discomfort. Her burrs were just plain old burrs, and her resin definitely wasn’t ‘sweet dew’. In fact, she sometimes found herself worrying about the adverse effect it might have on the human body if ingested. Surely you really shouldn’t be feeding young human bodies that stuff? But the humans were just that eager to depend upon Enoki’s special powers – powers that Enoki herself didn’t believe in.

After years mulling over her inexplicable sense of disgust, Enoki concluded that what she truly objected to was the way in which humans used their own yardsticks to affix meanings onto things that had nothing to do with them. They did this to objects around them, and even to elements of nature. People would pick vegetables that looked like parts of the human body, then feature them in TV news items about how ‘obscene’ they were, when really, the only thing making those vegetables ‘obscene’ was the gaze of the people looking at them. A firm udon noodle was, for some reason, compared to the tautness of the female body; varieties of fruits were assigned women’s names. When she put together all the information she’d accumulated over time, Enoki had no choice but to conclude that human beings derived joy from twisting things and attaching a sexual meaning to them. It was pathetic. Were they idiots, was that it?

And then to cap it all, they turned to Enoki, who wasn’t even a mother, and their mouths formed the words ‘breast milk’. Enoki hated the very sound of it: breast milk. There was a precariousness to it. It could ruin you if you weren’t careful. She couldn’t explain it, but Enoki knew that instinctively. She hated that she’d been dragged into all of this – that parts of her had been dragged into all of this.

And yet, the sadness those women felt – that was different. That was real. Enoki can still vividly recall the faces of all the women who came to visit her. She feels awful for women who lived back then, before formula milk existed. Of course, nowadays, with the humans’ deep-rooted devotion to the religion of breastfeeding, women still suffer a lot, but the invention of formula must have improved the situation at least a little. There is a big difference between having something to serve as a replacement when the chips are down, and having no such thing. Having other options is crucial. Women suffered in the past because they had none.

Speaking of which . . . Once upon a time there was a woman called Okise. She was raped by a man who threatened to kill her baby if she refused to have sex with him. He continued to rape her, then killed her husband and assumed his place as her new spouse.

That’s barbaric enough as it is, but it gets worse, because from that point on, Okise stopped producing breast milk. Her new husband suggested that if she couldn’t produce milk of her own, she ought to give her baby away to be looked after by someone else. Unable to nourish her own child, Okise had no choice but to hand over her beloved baby boy to someone else. If only there had been formula milk back in those days!

‘It’s okay, I can just use formula,’ Okise would have replied coolly, clasping her son close. The husband, realising how unfeasible his suggestion was, might have dropped the subject immediately.

Anyway, it turned out that the old man to whom the baby was entrusted had been instructed by the husband to kill it. Fortunately, though, he was won over by the adorable baby, and decided to raise the child in secret.

Funnily enough, the thing that the old man struggled most with was securing breast milk for the baby. As an old man, there were no strings he could pull in that regard, so he had little choice but to rely on the goodwill of various women he met to feed the boy for him. After just about scraping by that way for a while, the old man caught wind of a rumour that was circulating, and not long after, he appeared in front of Enoki.

That was how Enoki came to know of Okise.

The baby drank the ‘milk’ coming out of Enoki’s ‘breasts’ and grew up to be healthy and strong. Of course, this only consolidated the myth of Enoki’s magic, and so she became a bona fide legend. Yet Enoki still finds the whole thing very suspicious. It was just too outlandish to believe. The old man must have been feeding the baby something else as well. In any case, Enoki wants to believe that he was, because she definitely doesn’t have such powers.

Okise, on the other hand, subsequently gave birth to the child of her new husband, but because she couldn’t produce milk, the baby died. Not long after, a mysterious growth appeared on Okise’s breasts, and she went crazy and died too. Why is it that a woman who was repeatedly raped, then had her child stolen away from her, had to meet with such a cruel fate? Why did a series of such awful things have to befall her breasts? Well, gods? Don’t you think that’s overkill?

And the tale of Okise was just one example. The pain and the sadness that women felt when it came to breast milk reached depths Enoki could not fathom. Enoki’s sticky old resin was the last ray of hope for those women. So they clung to her. Through her thick bark, she sensed the enormous determination coming off their bodies. She felt, too, the tenderness and the strength of their breasts. How different they were from Enoki’s hard, knobbly ones. She felt like it was an insult to these women to call her organs by the same name. Enoki couldn’t bear it. These women were doing all they could to be saved by her non-existent supernatural powers, and she couldn’t do a thing for them. She knew that it was hardly her fault, but still she found it tough.

*

These days, hardly anyone comes to visit Enoki. She’s become nothing but an old relic. On rare occasions, some strange type with a fixation for legends of the past will take the trip out to see her. ‘Ah, it must be that one,’ she’ll hear someone say. They look at her as if she’s a museum exhibit and take photos. Women at their wits’ end no longer come to see Enoki. She’s sure they must still exist, but in any case, they have no need to rely on her any more.

Enoki has never for a second believed that she has the special powers that everyone thinks she has, but just hypothetically speaking, if she had, then she would have served a function not dissimilar to that of formula milk in the days before it existed. With this in mind, she feels she can finally accept the crazy commotion that had descended on her back then.

The shrine grounds are quiet. Enoki can hear a bird somewhere off in the distance. The wind ruffles her leaves indifferently. Now nothing, nobody, pays Enoki any attention. The days pass. The seasons change.

Enoki isn’t lonely. If anything, she is relieved. The pressure on her has finally lifted. Like it has always been, really, her resin is now just resin, and her burrs are just burrs.

At last, Enoki can be just a tree.

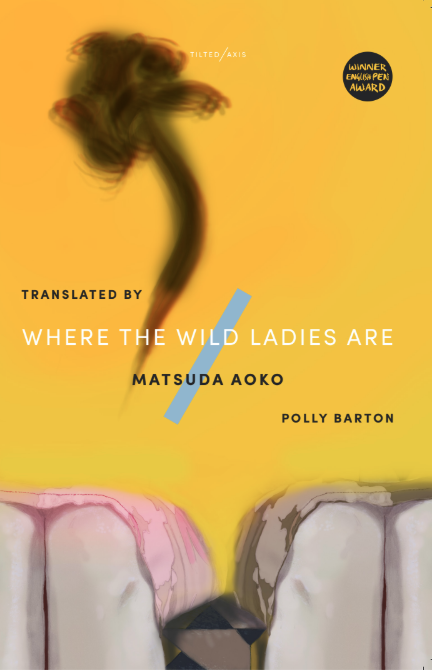

This story appears in Where the Wild Ladies Are by Aoko Matsuda translated from the Japanese by Polly Barton, published by Tilted Axis Press.

This story is part of our 20 for 2020 series, one of twenty timely and exciting new works from the Japanese published here at Granta.com. Find out more about the project here.