That’s the problem with the bones archaeologists excavate: they are dry as the grave. Silent. Dead. And even with all the panoply of modern scientific techniques that archaeologists can bring to bear on excavated skeletons nowadays, the bones stay mute.

Except for this one. A man that archaeologist Paul Gething excavated at the turning of the millennium from the burial ground outside Bamburgh Castle in Northumberland. Bones dug up on Thursday – Thor’s day – as clouds lowered and thunder spoke but no rain fell. This man, this son of Thunder, had a story to tell: a life that could be reconstructed, at least in part. As the results came in, we slowly began to realise that we could do something extraordinary: write the biography of a man with no name, and set this man, this warrior, in the context of the times and kingdoms in which he lived and died.

These are some of the objects that Paul and the team at the Bamburgh Research Project found that enabled us to tell the story of the Warrior, and his life and times during the early seventh century as the Kingdom of Northumbria, with its capital at Bamburgh, rose to become the greatest power in the land.

The Bamburgh Sword

It doesn’t look like much. A rusty bit of broken-off iron. But what you are looking at was, quite possibly, the finest sword ever made. Sword makers are faced with two contradictory demands. The weapon must be flexible, so that it doesn’t break, but it must also be hard, so that it can take, and hold, a cutting edge. To do this, sword smiths learned how to pattern weld, folding and forge welding separate billets of iron together to create a blade that could take the stress of battle and still cut through armour, bone and muscle. The sword excavated at Sutton Hoo, a kingly blade if ever there was one, was made of four billets of iron pattern welded together. The Bamburgh sword was made of six. It is a unique weapon – and one that was almost consigned to a skip. Excavated by Bamburgh’s first excavator, Brian Hope-Taylor, in the early 1970s, it lay unrecognised among his effects until his death. The sword – along with the trove of archaeological artefacts Hope-Taylor had in his house and garage – were saved at the last minute, just as house clearers were moving in. It was Paul who saw that the blade might be something special – but no one could have guessed what an extraordinary weapon it was.

Bamburgh Gold

The Warrior himself was a healthy, well-built man. What’s more, at a time (early-seventh century) when most skeletons show evidence of periods of dearth during their life, he was a man who had never gone hungry. As such, he was a member of the wealthy, warrior elite. And they were extremely wealthy. The Sutton Hoo finds gave some indication of the wealth an early medieval Anglo-Saxon court enjoyed and, at Bamburgh, the capital of the even richer and more powerful kingdom of Northumbria, the Bamburgh Research Project has excavated many small pieces of gold that were, simply, lost, and remained lost until archaeologists came along centuries later. The piece of gold above is an example. Probably once part of a book binding, it also illustrates how the newly-literate kingdom venerated books: they were objects of visual awe as well as repositories of learning.

Bamburgh Styca

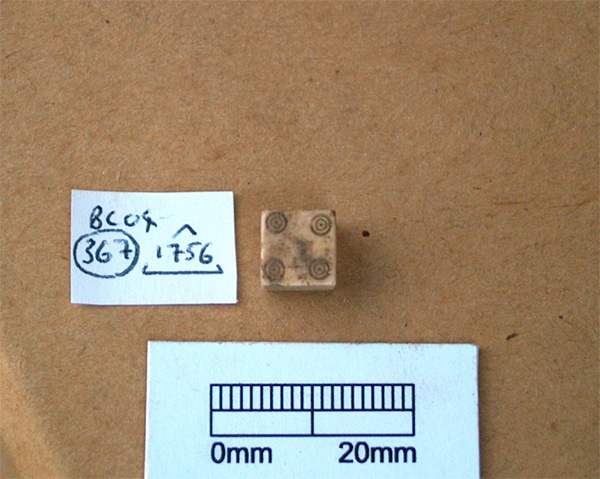

Bamburgh Die

Bamburgh Glass

Cover image © Matthew Hartley

In-text images © Paul Gething/Bamburgh Research Project