At Market I turn right and head towards Castro. A gym has moved its machines onto the sidewalk. Friday afternoon, less than a week into our second lockdown. There is only one guy on the gym part of the sidewalk. He’s lying on his back, knees in the air – and he’s balancing a tiny barbell on his groin as he thrusts his hips in the air then back down to the ground, up and down up and down and suddenly I’m missing you. I’m sure you’d have an opinion about what was going on here, you who wrote about sex kinks I’d never hear of, rosary beads up the asshole, pull them out slowly, one by one. What do you think? Is the guy getting off on this bar bell groin thing? Or did his trainer put him up to it? Is he pumping up his fucking muscles? Thrust up, thrust down, I wonder how long he’ll keep going – it’s frustrating that I can’t just stand and gape, that I have to keep on walking like I have somewhere to go. I see so few 3D humans these days – it’s frustrating I can’t pause him, can’t rewind, can’t even cheer him on. Go you superfucker, go! I’m reminded of a story about a toddler who had been raised playing on an iPad, and so the child was looking at an image in a print magazine, and they placed the tips of their thumb and pointer finger on the picture and spread them wide, then brought them back together and spread them across the picture again, looking confused, until the adults in this story realized the child was trying to zoom the magazine image, that they didn’t understand that all of life couldn’t be zoomed. After a year in isolation, I get it. The rules of the material world seem increasingly tentative. The few times a week I leave the apartment and enter the material world, I seem to glide through it, feet barely touching the ground, head swiveling from side to side. There’s little interacting. I’m like a ghost. I’m like you. Do you have any special powers? Can you see into peoples’ hearts, zap across dimensions? Do you silently flap through the night, your bright wings reflecting the moon, stunning the creatures who scuttle in the forest below?

When I return home my heart opens. This happens frequently, erratically. Imagine a time-lapse film of a bud twirling open into full bloom. My open heart feels floppy; gladly would it brush against anything, anybody. When I told Peter Gizzi that grieving had been good for his writing, he said it gave him a soul.

Why did you have to go? It’s intolerable you left and with such a brutal end. Most lung cancer victims – I read somewhere – die not of lung cancer but of infections or reactions to chemo. I was eager to take on your dying, to totally devote myself to your sickness. It’s as if this hidden cave in my psyche opened and out flew a swarm of bats wearing little nurse’s caps. No decision was involved; my drive to care for you was instinctual as those Monarch butterflies we saw that one Thanksgiving day in Santa Cruz, that traveled vast distances to roost in those specific trees, their branches all aflutter, the limbs of an Ovidian god-beast. My urge to care repelled you, who were all about extracting the last dregs from life, who were ravenous to live and live and live, hobbling and racing around with the cane Kaiser gave you because of all the blood thinners – if you fell down it would have been disastrous – you didn’t give a fuck about my research into chemo side effects. The bag of quick dissolving mints I bought that are supposed to help with nausea, you wouldn’t touch them. When we first met, your stories/memoirs about your self-destructive youth terrified me, though I loved the writing. Your past felt surreal, like nobody was behind the wheel and you were careening. Everybody who knew you when you were young agrees – and you affirmed this yourself, repeatedly – that I saved your life, that you would have been dead long ago without me.

The chase scene has begun. You sit upright on the edge of the couch, your attention absolutely fixed on the TV. None of that messy here and there/in and out/past and present. You are right here right now, watching with the focused precision of a laser sight on a Smith & Wesson, registering waves of awe, terror, delight. Your face fragments and coalesces like a claymation character, a series of ever moving parts that twitch and bulge, revealing emotion. Grunts, gasps, laughter, inrush and outrush of excited breathing. As the world rushes in through your eyes and ears, our living room becomes the cab of the car. You’re buckled in, careening into a dangerous future.

Your hospital room was so packed with visitors I had to leave. Your friends were possessive – and at the end when I put my foot down – no, this is about family now – it was a battle. Some people couldn’t conceive there could be a private Kevin space they couldn’t access, so fully you seemed to have given yourself to them. You would have been a better widow than I. You’d suffered bravely and sentimentally – far and wide – your widowhood would inspire people, bring them together – you would convince even those who hated me in life that in death I was a saint. And then the masses, ravenous for the kindness and generosity you perfected over the thirty-three years I was married to you – from quirky, unrelatable drunk to charismatic daddy you arose, capable of melting the hardest of hearts – could absorb you.

You knew to revere the dead. You wrote that finding where [the poet Jack] Spicer was buried satisfied ‘a huge longing in my own heart because, as I hope you have seen, for a man like me there’s no closure unless I go to the grave and fall down on it, as I did to John Ford’s grave in Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City, and embrace spectral memory as a living thing in my arms.’ On the bathroom wall hangs the snapshot you took of Frank O’Hara’s grave that one time we were visiting your parents in Smithtown and took a trip to the Green River Cemetery in Springs. Grace to be born and live as variously as possible. Online I look at photos of O’Hara’s funeral, July 27, 1966. Allen Ginsberg on a dirt path, head cast down, arm around the shoulders of Kenneth Koch. Women in flats and low heels, one wearing an era-iconic paisley sheath. Handsome Bill Berkson in a suit. I read about the ‘violent eulogy, full of raw fury’ delivered by O’Hara’s sometimes lover Larry Rivers, in which he describes O’Hara’s destroyed body in graphic detail. Mourners groaned and yelled, ‘Stop! Stop!’ O’Hara’s mother gasped. The text of the eulogy is almost impossible to find. I googled and googled and googled and finally in a YouTube video artist Skylar Fein reads it. Here’s my notes: His skin was purple where it showed through the white gown – his body was a quarter larger than usual – sewing every few inches, some stitches straight, three or four inches long – some stitches semi-circular and longer – eyes receded into head, lids blahbxncdck – quick gasps of breath – whole body quivered – tube in nostrils – he looked like a shaped wound – leg bone broken, splintered, piercing the skin, every rib cracked – a third of his liver wiped out. Rivers: ‘What good can talking about it do? I don’t know.’ To my widow self this is poetry. The bereaved clings to all the tender details of dying. When you’ve seen the unseeable, there’s no easy return. Nothing else makes sense.

Image © Shang-Ya Lin

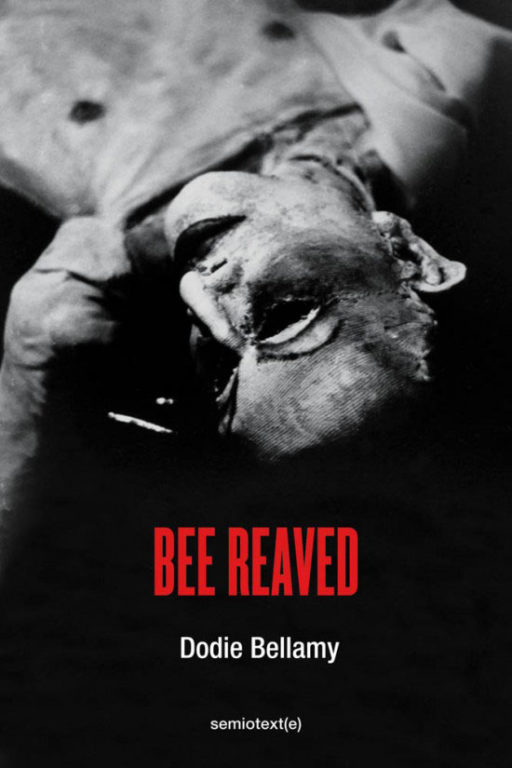

This is an excerpt from ‘Chase Scene’, collected in Bee Reaved by Dodie Bellamy, out with Semiotext(e) in October.