I am a fragment of my father, about whom I know nothing except for his name. My father is dead, in a tremulous and unspecified way; they speak of him in whispers if they speak of him at all. My father was named for a martyr who was named for a saint. I was named for my father. In English there are two ways to write me: with an i or an e, masculine or feminine. For most people, masculine was the default; doctors, teachers, social workers: not one of them got it right, and it never occurred to them to ask. The affectionate form, this is something people say about a shortened name, but they are wrong. To be littled inside of language, reduced, this is not an affectionate act. My own diminution was practical, not loving. People so often mistook me that my mother tired of correcting them. I have hated all my life the single syllable that remains to me: a ragged hangnail of sound, not really a word but a noise. I would mutter it under my breath sometimes, saying myself to incompletion, over again, forcing the f, rolling the r, and sensing in myself something abbreviated, sick; neither masculine or feminine, a stutter, a mistake.

*

When I was a child, I wanted to be a boy. Not in my body, but because boys did things. I envied their wonderful masculine reach, their way of being in the world, the vividness of even their suffering. At home, in an atmosphere fair suffused with Irish Republican fervour, I cannot remember hearing a single song about the women prisoners in Armagh Jail. Or anywhere else for that matter. Although the blanket protests, dirty protests, and hunger strikes conducted by their male counterparts in Long Kesh were the subject of extensive lyric treatment, the women’s no wash protest was never sung and barely spoken of, presumably because male shit was considered less disgusting than menstrual blood. The women in Armagh Jail were serially degraded and abused: strip-searched and sexually assaulted as a matter of policy, but the language did not exist for the specific pain of their treatment; an embarrassed silence hung over them all. The Catholic church had trained us for this silence. Male suffering may be exemplary, honourable, possessed of a refining fire. Men endure what is done to them, they transmute abuse into heroism. Female pain is only ever squalid, there is no dignity in our survival – no grace – just a grubby and stubborn persistence. When we are abused, a portion of the perpetrator’s sin adheres to us. The church venerates those murdered virgin saints because survival itself is the medium of our shame, its receptacle and conduit. Men may suffer and die for a cause. Women have no cause. They suffer because they are women. This vulnerability is sordid. On the mantel, a row of dead women with the arrested pre-pubescent bodies of Olympic gymnasts; they smiled benignly as their torturers lopped and gouged at their perfect porcelain limbs.

*

My mother was fifteen when she gave birth to me. She would never say so, but in a purely objective and practical way my being born had ruined her life. I cannot remember a time when I was not aware of this, of being a tactile fragment of sin. There would be no abortion, legal or otherwise. Instead, there were desperate remedies, each more implausible and reckless than the last. It did no good, my grandmother’s cunning had failed her. Whatever was me would cling to life. My mother, in turn, would cling to me. For her, I was not a source of shame or a form of punishment. I was a person. But still, the fact remains: if I had not been born she would not have been married off to that man. I will not say his name. I will preserve him instead as the stifling tang of wild garlic, as a brain-dead spasm of incontinent rage. He was thick and bestial; he had thick and bestial friends. He gave us my brother. It was the single decent thing he did in the world. His family would not mix with us because we were tinkers, and a tinker is the worst sort of taig you can be. I do not know what he wanted with us, with her, but she was very beautiful, and he expected gratitude. Who else would touch her, want her now, damaged goods, with a baby in tow?

*

Aristotle says that women are merely matter; they cannot contribute form to future generations of offspring. He suggests that women are unfinished or deformed. He does not differentiate between unfinished and deformed, but uses both terms interchangeably to mean inferior. Tomas Aquinas states that women are deficient and, as it were, unintentional; that women are caused by weak semen or humid atmosphere, that women are both accidents and mistakes. I was not intended; my mother’s misfortune, my father’s mistake, doubly deformed. Because, if a woman is an accident, an accidental woman is a what? Growing up, I understood that I was inferior for being a girl, but also inferior for not living up the girl I was supposed to be. My body was an angular mass of fidgets, my hair a thicket of honey-blonde knots. I bit my nails, I rolled in the dirt. I climbed trees and frequently fell out of them. I was unequal to the dresses my grandfather brought for me. I loved their important gaudiness; their swags and ruffles and flounces, but I ruined them soon as look. All of my clothes became torn or stained. I didn’t want them to. I wanted to wear the dress and climb the tree, but the hem would snag on a branch; I’d lose buttons and bows to a tussle with gravity or dogs. I couldn’t have both. Someone was always telling me that: you can’t have both. So I stopped wearing dresses. I loved animals, dogs and horses especially. I had no interest in riding horses, I thought bits and bridles and leads were the most awful things in the world. I liked to see animals wild, living their life without reference to me. I thought wearing a collar must be like me, putting on my itchy grey school skirt, or the stiff school shoes that creaked and pinched as I walked. I liked an animal to choose me, to eat from my hand, to cooperate because they trusted or were pleased to see me. Otherwise, where’s the trick? What’s so special? Any fool can compel another with a big enough stick. The parents of middle-class English girls paid hundreds of pounds to seat them in a saddle and walk them on a tether, in a circle, round and round, for hours. This mystified me. Who was this for, and why? Not a relationship, a pact of dull compliance. I liked a horse running free, or to watch the boys at Ballinasloe or Rathkeevan: shirtless, bareback, bending low, about a million miles from that sawdust circle with its prissy jodhpurred somnolence, its peevish ramrod spines. My grandfather had a tea tray, the print on which was a hologram of running horses; tilting it this way and that in my lap was an obsessive occupation. There were also lenticular prints of The Sacred Heart of Jesus, Our Lady of Sorrows, and best of all: wolves. I was truly obsessed with wolves; with jackals and hyenas. I was similarly bloodthirsty, accustomed to violence as both a narrative and political currency. I wanted movie-monsters, spine-chillers, slasher-flick psychopaths, Jason and Freddie. I wanted haunted dolls, possessions, dancing skeletons, talking pumpkins, ghosts and zombies, freaks and mutants. Werewolves were best of all. Disney films bored me: all those gown-bound princesses for whom rescue was functionally identical to capture. The animal characters were better, but the girls, with their damsel lashes, bore no relation to the real-life wild, where the female of the species was always bigger and stronger. Walt Disney clearly agreed with Aristotle: female animals were adapted from a standard male template with some cursory softening in strategic places. They were always pretty, delicate, symmetrical. They spoke with perfect diction. Unless they were the baddies. Or the comedy relief. Feminine is the word I’d use, that fiendish intersection of gender and of class.

*

There are people who talk about The Gypsy Life as a vista of limitless freedoms. Morons is the polite term for such people. The old codes are as strict as they are exhaustive. For my grandfather’s generation, and for those who came before, the world is divided into wuzho and marime, a distinction for which the body is the most immediate map: the upper body is wuzho, that is pure; the lower body is marime, that is or impure or defiled. Upper and lower-body clothes must be washed separately. Women’s clothes must be washed separately. Spit and vomit are wuzho, menstrual blood is marime. And marime can’t be washed away, it spreads through contact, and its contagion is both literal and moral. Things that become marime must be burnt, or thrown away. Where gadje hygiene seeks to cover and contain dirt; accumulating rubbish in bins within the home, for the old men, polluting dirt must be placed outside, as far away as possible. Only dirt that cannot be removed must be contained. The hem of a dress, skimming the ground. Modesty is not merely a mode of behaviour, but a spiritual condition. The wuzho/ marime binary proliferates a hundred thousand rules around ritual avoidance and boundary maintenance: between the upper and lower body, the inner and outer body, the inner and outer territory; between the male and the female, between ourselves and the gadje. To cross any one of these boundaries is to be hopelessly marime. To exist across is the worst thing you can do, or be. I had always understood myself as marime. The result and the evidence of marime-ness in others, but also inherently polluted and polluting for being somehow both. Which is to say half-blood, poshrat, or partial. Which is also to say not quite a girl. Which is also to say queer.

*

Both has a way of being neither. Rather, we feel this otherness in ourselves as a lack because the language we have for it does not allow us to apprehend it as a positive quality. Queerness is something done to the ordinary; it does not constitute itself. It can only exist in reference to straightness. It is an either-or proposition, and this is the hidden and historical violence of queer, it assumes a stable centre from which we deviate, or to which some species of deforming damage is dealt. It has a melancholy aura, a yearning to establish some centre of our own. What is extra in us, what is abundant and branching and alive, feels like a hole, like a bottomless pit into which we fall and cannot fill. That is the cavernous quality of my own queer desire. Because I can only understand myself as whole in the act of reaching towards another, in that generous extension of affection, in the compulsion to confirm a felt mutuality, a compassionate commons. What I mean to say is, we talk about queerness through desire because it is only through desire that we can comprehend ourselves as whole, as more. Being bi is not, for me, a primarily sexual proposition. Being queer does not pertain to gender or sexuality alone. It is the way I am an edge, all edge: border-stepper, half-breed, gypo, taig, any of the names by which I might be known or claimed; the marime part of being. Bi has no language, has no politics, for these require a centre. Straight people tell me that I am confused. Gay people tell me that I am greedy, or that I should pick a team, that my love is somehow anomalous, fraudulent or excessive. But my desire does not define or complete me, it extends me, beyond the tyranny of woman, beyond the stupid jagged fragment of my name.

*

For there are all manner of lacks and deficits in me, all manner of places I have been maimed or truncated. I have no father, and I have no home. When people ask me where I am from, I do not know what to tell them. I am neither English or Irish. I am not Gypsy or Gadje. I have no mother tongue, no local affinities for a native territory. My accent itself is a ceaselessly shifting terrain, a rough map of halting sites and passing places; of estates and camps and squats, of transition and precarity, a relentless moving through. And I am not woman. Not in the ways I am supposed to be. At the age of thirteen my developing body became an incitement to violence, a site and occasion of trauma. And so I shaved my head and I stopped eating. This was, in the first instance, defensive: my armour against the hungry objectifying gaze of predatory men. But more than this, it was a renunciation of the world-view to which that gaze and its crass aesthetic judgements belonged. It made me, of course, another kind of target for another kind of violence. But I’d rather their ridicule than their desire; I’d rather their hate than their lust. If I cannot choose but to be abjected, I will at least choose the manner of my abjection. If I am to be torn down, I will go down swinging, denouncing that shitty, heteronormative value system and everything it wanted or expected me to be. I was already an outsider. I lived my life pulled between poles of exile and imperfect assimilation. Very well, I would own the outside. I would own my hunger, my anger. I would hone my edge.

*

A friend of mine wishes me Happy Bi Visibility Day! I am baffled. Talking about bi visibility feels like talking about warm snow, or dry water. Bi is an occulture, the visible is not its spectrum. We write and think a great deal about bi erasure, but supposing the opposite of erasure were not visibility, but opacity? The right to and the pleasures of the unseen; to live without the pressure to define or to perform, in the deep polymorphous silence of desire. I would say that, of course. A lesbian friend tells me that I am hiding in plain sight, inside a tedious straight marriage, benefiting all the while from an ingrained assumption of heteronormativity. And on a systemic level, of course she is right: the expectations of others form a skin of concealment. But still. I have not ceased to desire. I have not ceased in my outward or inner otherness. Each day I must negotiate my awkward fit inside this marriage, inside this straight and settled world. I am marked out by my clothes, by my decision not to have children, by my shaved head, by my unmade face, by my accent and grammar, by the depth and the difference of my cultural references, by the art I make, by the digital world I reject, by the bread I bake and the plants I grow, by the pit bull dogs I train, by the holidays I do not keep, by the saints I venerate and the incense I light, by my communism, by my veganism, by my family ties and our inherited traditions, by the way I take my coffee and tea, by the music that has sweetness and meaning to me, by the milestones of childhood experience that are alien to me, by my dislike of crowds, of parties, of people, by my contentment in my own company, my aversion to the visible, to the obvious; the inviolate privacy of my desires. It is all of this, and none of this, and more than this. Because I cannot separate my bi desire from everything else that I am. It is a way of meeting and being in the world, indeterminate, ambivalent, but open. And perhaps I am not a fragment of my father; perhaps my name is node, a seed. I might grow into English along either axis: masculine or feminine, neither or both.

Image © Lihoman

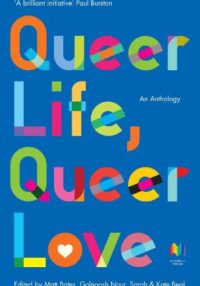

This essay is published in Queer Life, Queer Love, an anthology forthcoming from Muswell Press.