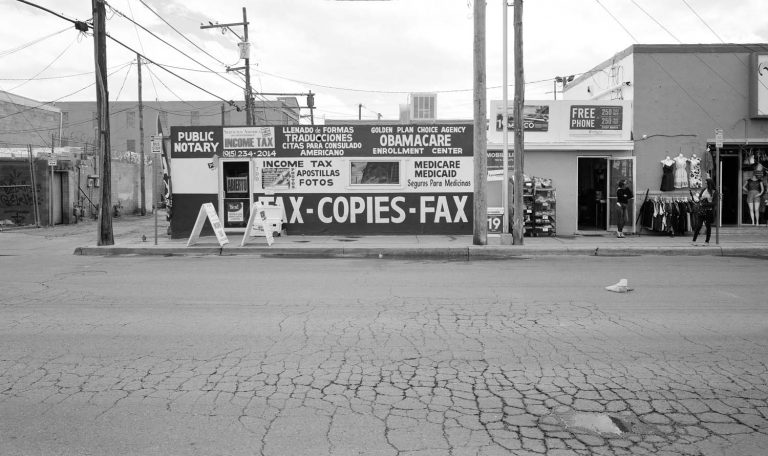

The twin cities of El Paso and Ciudad Juárez lie either side of the US–Mexico border. My father grew up in Juárez, often traveling from one city to the other for school trips or work. Though he later moved away, I remember frequent trips back to the border as a child, journeys that made my love for its peculiarities take hold.

When I asked, my father found the prospect of narrating his years in Juárez daunting, until he realized that he had been doing it fitfully ever since I was a kid. His stories had a significant influence on my understanding of the two cities, and I became fascinated by how different they each used to look and feel only a few decades earlier, back when a system of transnational streetcars linked them together, and before globalization – in the form of unequal trade agreements – altered them socially, economically and geographically.

Those outside of Mexico familiar with Juárez tend to know it for its infamies. The femicides of the late nineties cemented an infernal image of the city amply propagated by novels and films. Since then, the war on drugs has precipitated the decay of public life along with a rise in violence and corruption. The media has focused its attention on the gruesomeness of these issues, putting past and present histories of everyday life at risk of getting lost.

Since personal memories do not leave material traces, and seldom align with official monuments, there was always something missing whenever I tried to square my father’s recollections of the city with its present landscape. The past cannot be restored, but it can be conjured for insight into the current state of things.

I have tried to capture my father’s voice and give shape to his anecdotes. His involvement and generosity were instrumental in this project, and while he stood next to me when I made these pictures, any verbal or visual oversights are entirely my own fault. I asked him whether evoking some of these episodes had been painful. The real torment, he told me, was all those details, textures and voices that were now out of reach. Otherwise, seeing and thinking about these places brought him a unique joy that was difficult to describe.

1958

The first time I crossed over to ‘El Chuco’ was on a zoo trip with my kindergarten group. More than any detail about the city, I remember my mom’s anger because I stained my best shirt while moving a soda crate. The second trip I remember more vividly. It was to the mythical JCPenney. We took the transnational trolley, a streetcar which linked the two cities directly. The journey felt tediously long despite the short distance. We had to pass through immigration, and some passengers even had to get vaccinated. Overheard conversations had led me to believe things were better on ‘the other side’, but I soon realized both cities looked more or less the same. I was even uncertain if we had reached El Paso. A few sights along the route became my points of reference over time: the old customs building, the scale version of the Spirit of St Louis above the entrance of a cantina, the shiny clay indios in sarapes flanking the door of Don Marcos Flores’s house. A former municipal president, Flores had a gift shop close to the Santa Fe bridge that also exchanged currency. My grandma Esther used it whenever my aunt in Los Angeles sent her money. Don Marcos, forever standing by the entrance, greeted her by name, which made me feel important.

La Tuna was the minimum-security prison where la migra sent the mojados after repeated deportations. It is about twelve miles outside El Paso, on the border with New Mexico. My dad served a brief sentence there, which forced my mom to also work illegally, as the pay was much better on the other side. She found a job babysitting the children of a wealthy family whose mother suffered from a weak heart. When I was around eighteen, my mom confessed to me that it had been my dad’s spiteful mistress who had denounced him to la migra. Some years later, my dad had to request an official pardon from the State Department for all the times he had been deported and incarcerated before he could receive his American citizenship.

1961

My uncle Chico was an insecure man who struggled with addiction all his life. He was my mom’s only full sibling, so their bond was special. She said he liked showing me off in the cantinas when I was little. His tattoos fascinated us, but he would hide them, at least while we were kids. Catching sight of the naked woman on his arm was quite something. As a young man, he had a long and tortuous relationship with a girl named Calina. After getting his American work permit, he went from job to job until he reached New York. He would send my grandma money at first, but then he disappeared for three years, causing my family a great deal of anguish. He returned one day without warning or explanation, and quickly married a flamboyant woman named Refugio, but then left her while she was still pregnant. Refugio did not want the child either, so my cousin Panchito, who was never cared for, became an addict, and then a thief. Towards the end of his life, my uncle relied on his relatives to employ him as a handyman or nanny. He was detained several times for possession and was occasionally sent to a rehabilitation center that did little for him.

Like most kids, I was a fan of the comedy duo Viruta and Capulina, whose films I had seen at the matinees in the Variedades and the Coliseo. They were visiting Juárez, and a meet-and-greet was planned in the large lot opposite the General Hospital. My friends and I arrived early. The organizers kept pushing back the start of the event. We felt drained after a couple of hours of waiting in the heat, and we were considering leaving when the comedians finally showed up. They looked hungover, lifeless and did not perform any of their famous routines. The duo hurriedly shook our hands, and that was all. I have never understood the cruelty of making children wait in a dusty lot under the desert sun. Few experiences in my life have been as disappointing, to the extent that I feel something inside me changed after that day.

Sign in to Granta.com.