‘It was a sunny day in April 1960. I took a ship to Chōsen [Korea] from the port of Niigata, a north-western city of Japan. When I saw my mother for the last time, she was crying. She kept saying, “Please don’t go . . . Please change your mind.” Every time I remember that moment, I can’t help but cry. I was only twenty-one years old.’

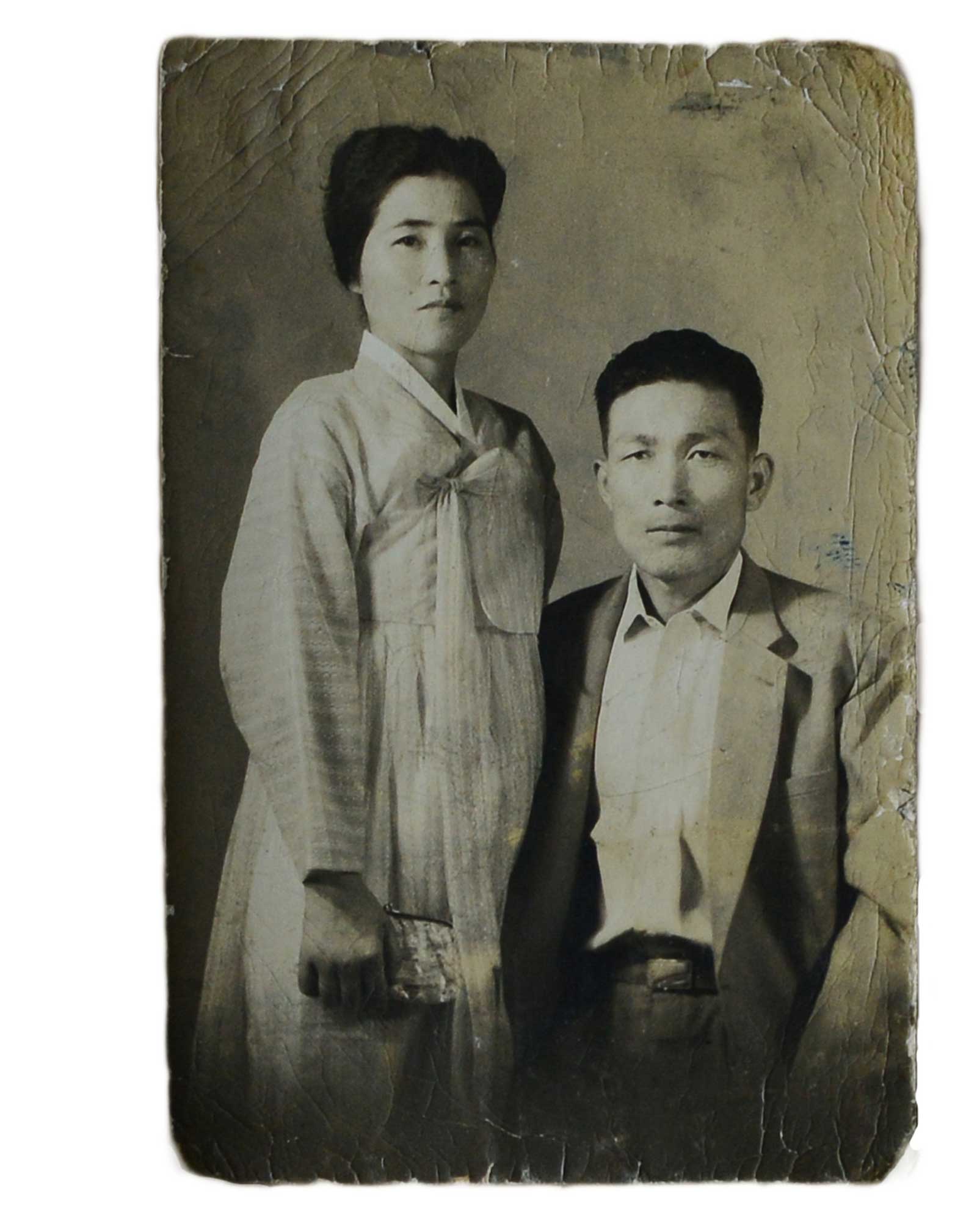

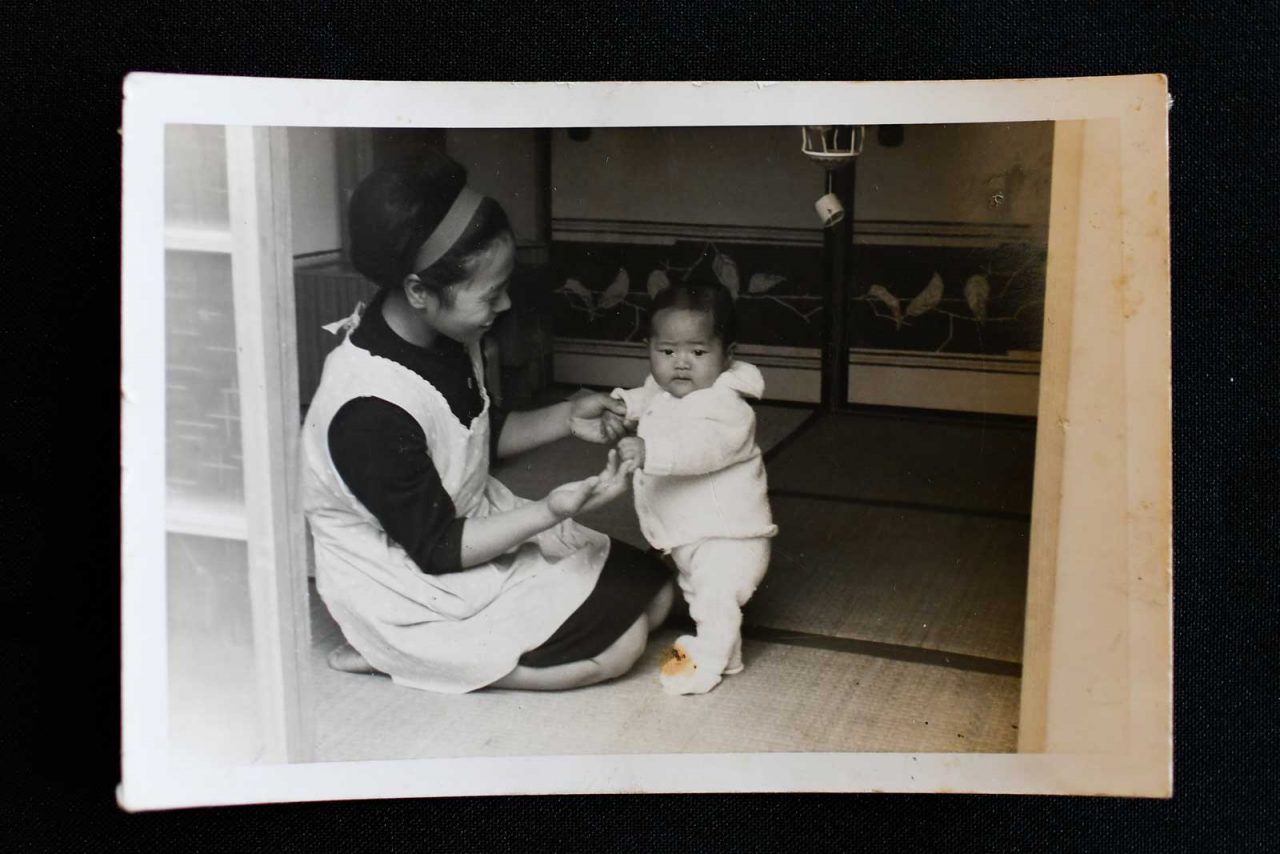

In her room in the port city of Wonsan in North Korea, Mitsuko Minakawa sighs while holding a folded handkerchief. She was born in 1939 in Tokyo and was raised in Sapporo. After graduating from high school, Mitsuko enrolled at Hokkaido University – she was the only female student among the one hundred students in her class. In the second year, Mitsuko met a Korean man, Choe Hwa Jae, and fell in love.

In the 1950s, there were about 600,000 Koreans living in Japan. At that time, some of them succeeded in business and gained an education, but the majority were disadvantaged legally and socially, suffering from poverty, as well as ethnic and occupational discrimination. As of December 1954, the total unemployment rate for Koreans in Japan was about eight times the total unemployment rate for the Japanese.

One year later, married, Mitsuko and Hwa Jae decided to leave for North Korea, participating in the massive ‘repatriation program’ from Japan to North Korea that took place between 1959 and 1984. According to the Japanese Red Cross Society, 93,340 people moved to North Korea during that period, the vast majority of whom were Zainichi Koreans (ethnic Koreans who are permanent residents of Japan). However, that number also includes about 1,800 ‘Japanese wives’ (Japanese women who married Zainichi Koreans) and a small number of ‘Japanese husbands’ who accompanied the ‘returnees’.

In August 1948, the Republic of Korea had been founded in the southern part of the Korean peninsula, and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in the north the following month. Though more than 95 per cent of the Koreans who moved to North Korea were originally from the southern part of the Korean peninsula, they returned to the north, welcomed by the Democratic People’s Republic, which hoped to rebuild the country after the Korean War and to demonstrate the superiority of the socialist system over South Korea.

Mitsuko has now lived in North Korea for almost sixty years. She can see the sea from the window of her room, and Japan across from that sea. Many returnees thought that the unification of the Koreas might happen in the near future, so that they would be able to go back and forth between the north and south. The Japanese wives who crossed the sea also believed that they would be able to move freely between Japan and North Korea after a few years. This would prove untrue.

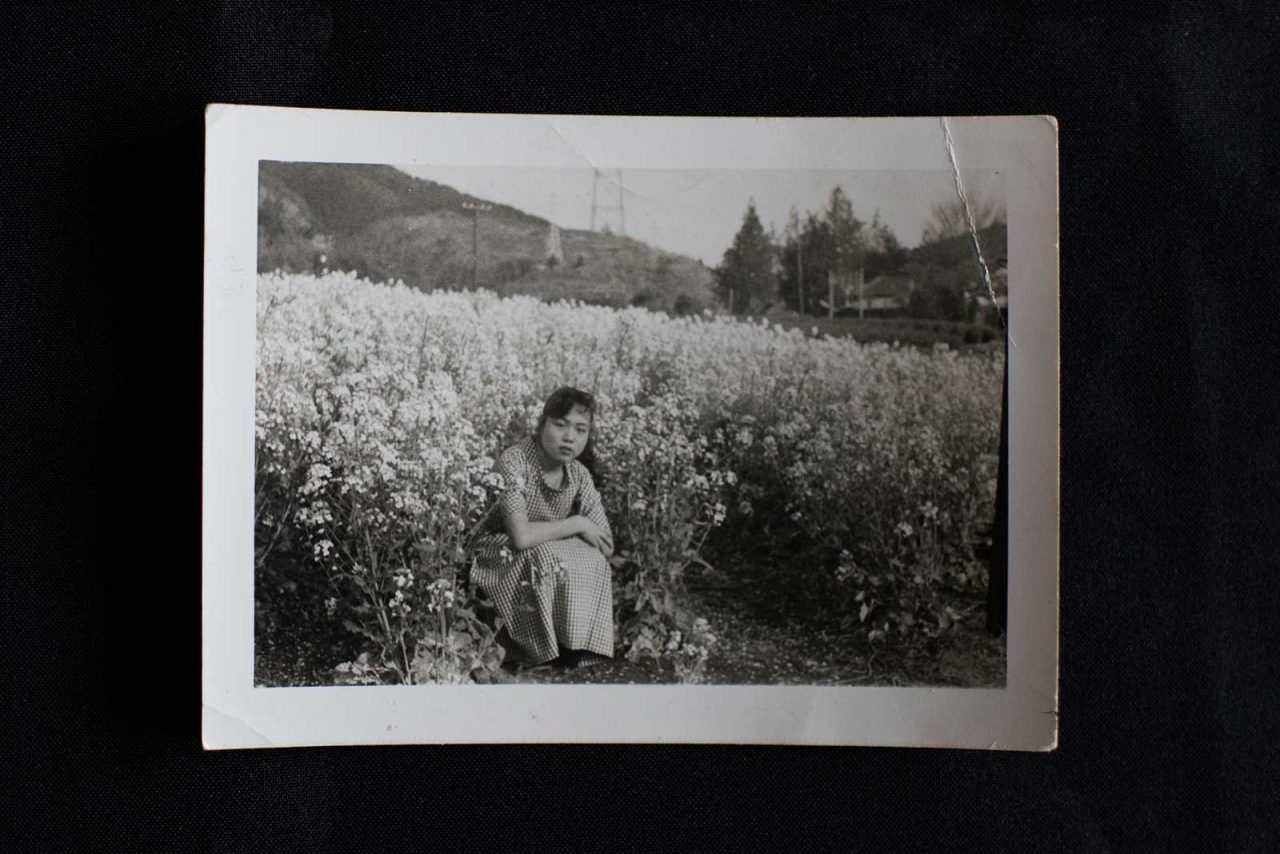

Since 2013, I have travelled to North Korea twelve times and interviewed and photographed eight Japanese wives in Pyongyang, Wonsan and Hamhung. Three of them have passed away during this period. I realized that they shared a common desire: to visit their hometowns in Japan. I decided to take pictures of the special places they held in their memories and print large photographs onto tarpaulin fabric.

I showed these prints to the Japanese wives and took photos of them observing images of their hometowns: the parks, beaches and shrines. Their reactions were varied. Ms Suzuki quietly approached the print and kept looking at it for a long time. Ms Ota suddenly smiled and kept touching the print. Ms Arai sat in the formal Japanese seiza style in front of the print.

Human memory is fragmentary, delicate and complex. This year will be the sixtieth spring that Mitsuko spends in Wonsan. She looks at the sea and says, ‘Every May, the acacia flowers are in full bloom here and I can see them from my home. Their scent enters the window when I open it. Each time I smell them, I remember my hometown of Sapporo.’