As a non-driver, and a non-native English speaker, I felt a certain degree of affinity with Vladimir Nabokov when I had the chance to do a short road trip in Texas recently. I stayed at my very first out-of-the-way motel (damp linen, unexplained human screams in the middle of the night, impeccable quirky 70s décor: my heart melted). The Outpost Motel, as it was called, stood just off a country road that eventually intersects with US Route 290, a mile or so to the north, but the immediate surroundings featured nothing but tall weeds and a lone Catholic church.

Perhaps it was wishful thinking to imagine that this brought me back to the time before the interstate highway, when America’s roadside infrastructure was more disparate and easier to categorize. A time when the separation between the highway and America’s hinterland was harder to place. But the ever-confident tone of self-marketing in America, consistently and regardless of the actual quality of the service delivered – See for yourself what makes our rooms second-to-none, read a sign at the Outpost – greeted me in much the same way it would have greeted Nabokov on his cross-country trip sixty years before.

*

In 1956, Vladimir Nabokov was defending his novel Lolita against claims of anti-Americanism. He called them preposterous. The accusation of anti-American bias in Lolita was based on the novel’s treatment of postwar America’s mass culture, which the novel’s European narrator does register with a mixture of skepticism and exhilaration. But this contempt, Nabokov wrote in an afterword to the book, was Humbert’s, not his own. His intention, he argued, was to analyse America from the perspective of a newly-minted American author. To steep himself in the baffling world of roadside service that seemed to characterize his new home.

Lolita chronicles America’s mass media culture – Hollywood, soda ads, glossy magazines – but focuses on the country’s relationship with the automobile, which had created two new all-American settings for Nabokov to explore: the sprawling yet self-contained suburbs on the one hand, and a booming roadside service system on the other. Nabokov tackles both. He describes the suburb’s stifling social environment in the first part of the book — with its polite book clubs, lakeside picnics, intensified domesticity and class uniformity. Part two turns to roadside architecture, a sampling ground for another ritual of modern living, based on leisurely movement and family vacations. That section begins: ‘It was then that began our extensive travels all over the States,’ but immediately finds itself stalled at the roadside inn. ‘To any other type of tourist accommodation I soon grew to prefer the Functional Motel – clean, neat, safe nooks, ideal places for sleep, argument, reconciliation, illicit love.’

To write about America, Nabokov needed the springboard of a typical north American set. His choice of the motel was a way of claiming his place as an American author. ‘I am trying to be an American writer and claim only the same rights that other American writers enjoy.’ This turn of phrase is, as often with Nabokov, coy. He combines a tongue-in-cheek critique of the cultural void of the roadside landscape with a play at increasing his American readership and sales by writing about something that is inarguably American. Nabokov’s Russian novels, written in Paris and Berlin, had always retained a strong émigré flavour which Lolita, in spite of being narrated by an expatriate, finally managed to shake off. Why? Because it was about America.

Lolita, in this sense, is the first modern American road novel. The book moves from the New England suburbs to the open road, and covers two cross-country road trips. In these pages, Nabokov writes a kaleidoscopic portrait of the American motel, where the details of roadside establishments form a picture of America’s postwar restlessness.

We came to know ⎯ nous connûmes, to use a Flaubertian intonation ⎯ the stone cottages under enormous Chateaubriandesque trees, the brick unit, the adobe unit, the stucco court, on what the Tour Book of the Automobile Association describes as ‘shaded’ or ‘spacious’ or ‘landscaped’ grounds. The log kind, finished in knotty pine, reminded Lo, by its golden-brown glaze, of fried-chicken bones. We held in contempt the plain whitewashed clapboard Kabins, with their faint sewerish smell or some other gloomy self-conscious stench and nothing to boast of (except ‘good beds’) . . .

Nabokov’s pedantic francophone narrator, with his high-modernist aesthetic principles (that ‘Flaubertian intonation’), was one step ahead of America’s contemporary writers in setting a story in motels and on highways. Jack Kerouac’s hit road novel – written two year later – described a tunnel-like vision of driving which, except for the rhythm of jazz music, fails to linger on the Americanness of the surroundings. In On the Road, the highway is an inward-looking place; driving always means anticipating the next destination, and focusing on the secluded space of the car. The reason Nabokov’s roadside America is so vivid is because of the receptiveness of his outsider narrator’s perspective, a perspective which he admittedly cultivated.

As Robert Roper points out in his road-focused biography of Nabokov’s American years, America made Nabokov more scientific, less flâneur. This was partly due to his renewed commitment to the study of butterflies – he had a new side-gig as the unofficial curator of lepidoptera for Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Travelling west with his wife and their young son whenever he was not teaching at Wellesley College or, later, at Cornell, Nabokov not only relished in exploring the landscapes of Wyoming, Colorado and Montana, he also collected butterflies for the museum. Nabokov would be on the road for months at a time, and the scientific mindset that came with lepidoptery extended to his observations of the non-natural world. In the ten years following his arrival in the United States, his general approach to reading and assimilating his American surroundings – especially the unfamiliar and ever-shifting American slang – led to a remarkable linguistic metamorphosis: American parlance is reflected across Lolita, and marks the author’s conscious transfer from Russian émigré to American, fully fluent in the cultural and its linguistic ticks.

*

But for months before Nabokov began work on the book, he took notes. Sitting at the back of public buses, he jotted down teenage slang, setting it aside for his unfortunate heroine. Nabokov was a non-driver, and so on family road trips his wife Véra acted as chauffeur. When Nabokov was not reading road maps, he would be collecting road signs, recording the repetitious names of the hotels and mocking their crass publicity materials, all of which filtered into the final book:

‘. . . all those Sunset Motels, U-Beam Cottages, Hillcrest Courts, Pine View Courts, Mountain View Courts, Skyline Courts, Park Plaza Courts, Green Acres, Mac’s Courts . . . Some motels had instructions pasted above the toilet . . . asking guests not to throw into its bowl garbage, beer cans, cartons, stillborn babies . . .’

He also kept coming back to images of roadside vegetation, awkwardly cohabiting with parking spaces and picnic tables. These too were thrown into the mix of the book, along with renditions of landscapes which the narrator explicitly links to classical landscape painters. In his road diary of 1951, half-way into the writing of Lolita, Nabokov made a note to remember ‘Lorrain’s clouds inserted and fading into misty azur.’ Later on he made another about a ’grim El Greco horizon’. All of these impressions, along with the way the roadside vegetation changed from one State to the next (‘the first yuccas, the first mesas’) find themselves copied, almost word for word, into the final text:

There might be a line of spaced trees silhouetted against the horizon, and hot still noons above a wilderness of clover, and Claude Lorrain clouds inscribed remotely into misty azure with only their cumulus part conspicuous against the neutral swoon of the background. Or again, it might be a stern El Greco horizon, pregnant with inky rain, and a passing glimpse of some mummy-necked farmer, and all around alternating strips of quick-silverish water and harsh green corn, the whole arrangement opening like a fan, somewhere in Kansas.

*

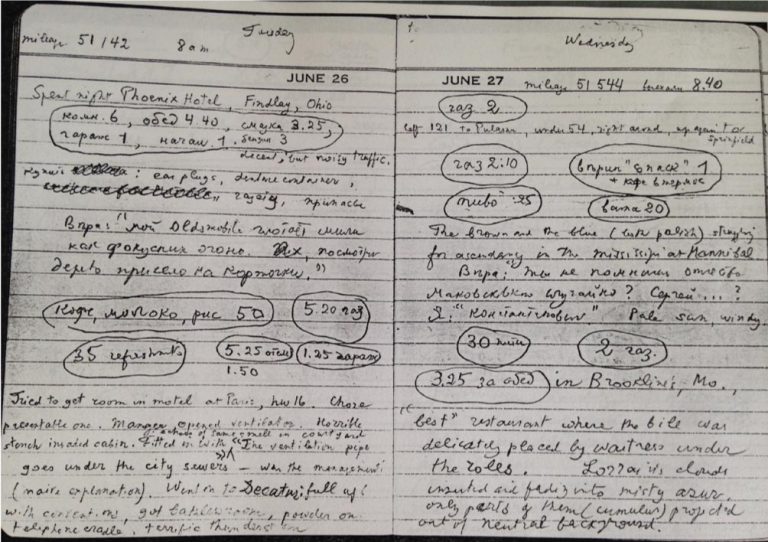

I went through Nabokov’s road diaries while I was writing my thesis, some years ago. I remember how shockingly small his pocket diaries were, how fragile the jotted thoughts in black ink on the material page. How had so much come from so little? It was strange to see so much roadside trivia appearing alongside Nabokov’s now-iconic description of the western landscape. His handwriting, neat as a schoolteacher’s, divided the notes into two camps. In English are impressions of the road’s landscape, many of which appear in Lolita. In his native Russian are practical notes on the price of oil, food or rooms for the night. A friend patiently helped me translate the following items, which share a page with a lush description of landscapes under meteorological change:

gas 2

breakfast 1.70

‘snack’ 1

oil 3.25

garage 1

lunch 4.40

tip 1

little things 3

5 for the room

1.10 little nothings

lunch 2.50

breakfast 1

wine 1

Elsewhere I find 70 cents for ‘coffee and milk’, 60 cents for ’beer and ice-cream’. Mileage and departure time are noted every day. In Colorado Springs: $7 for a cabin (the word he used, in Russian, could also have meant the cabin of a ship, according to my friend, as ‘motel’ did not, and as far as I’m aware still doesn’t, translate easily into other tongues). Some of this pricing does creep up in Lolita, but mostly it is personal.This is the mark, I think, that Russian was still his automatic language, his go-to way of expressing basic thoughts. He must have always had to stretch himself out of automatic thought to write in his new American language.

Vladimir Nabokov, Page-a-Day Diary, 1951

The notes show how Nabokov’s first-hand experience of the road was the foundation for his writing of Lolita, and his way of writing as he travelled, capturing impressions that he would later reinject into the novel. He also jotted down in Russian a couple of remarks from Véra at the wheel: ‘My Oldsmobile swallows miles like a fire-eater,’ she exclaims, somewhere between the price of breakfast and the latest amount spent on oil. Russian was of course the language of personal communication among the Nabokovs. A note about yucca blossoms being filled with moths will be translated from Véra’s Russian into Humbert’s English, but along the way they transform from moths into little creeping white flies: it was important that Humbert, a deeply unpleasant narrator, should get his butterflies wrong.

Notes about mediocre motels form an amusing contrast with the romantic considerations of mist and clouds: ‘Spent night in Old Orchard Cabins — never again. Blue roofs, blue chairs, even cut arm of tree circled with blue. Stinky river behind.’ The quoting of an awkward management note — ‘“Do not use water for drinking purposes” — sign in bathroom’ —represents the abrupt rhetoric of motel signage he later sardonically quotes in the novel:

We wish you to feel at home while here. All equipment was carefully checked upon your arrival. Your license number is on record here. Use hot water sparingly. We reserve the right to eject without notice any objectionable person. Do not throw waste material of any kind in the toilet bowl. Thank you. Call again. The Management. P.S. We consider our guests the Finest People in the World.

In another entry, Nabokov writes: ‘Went on to Decatur: full up with conventions, got bathless room, powder of telephone cradle, terrific thunderstorm.’

The contrast between the awe of nature and the frustrating gimmick of omnipresent roadside services with their unrealistic claims on the average motorist’s appetites appears again and again in Lolita, a contrast Nabokov embues with manifest comedic potential.

Sometimes, though the patchwork of images collected from the roadside evoke a melancholy mood, as in the following entry:

June 25th: Overcast morning, coldish and damp. Puddles. Gas station. Small red general motors truck, with N.Y. car carriers just in red in yellow square on drivers door. Island of grass with white clover, surrounded by whitewashed stones, with sign in the middle: Diesel Fuel.

In my reading of this material, I get a picture of unusual loneliness. Nabokov is miles away from his privileged upbringing, cold and damp on a gas station forecourt, staring at a sign for diesel. The station itself is incongruous in the rural landscape with its white clover, oddly disconnected from the world around it. Humbert, in a way that recalls Nabokov’s diary, picks up on the mystique of these ubiquitous service stations, which always undermine his aesthetic fantasies of classical European landscape painters. HH can drive through these with his kidnapped stepdaughter in plain sight, and feel safe, but at the same time they always remind him of the fact that he’s an outcast, that he can never stop travelling.

For Nabokov, there was no going back home. The Russia of his childhood was a political entity that no longer existed, and consequently a personal reality which could never be visited again. Modern America, where the transient is welcomed everywhere, where the average man is always on the move, was as close as he ever got to finding a home in exile, albeit a temporary one. By writing about life at the motel in the 1950s, he was writing about the arch-American literary figure of the outcast, but he was also writing about the most mundane experiences of his American readers. On one of their road trips, Nabokov’s son Dmitri, aged six or seven, told a gas station attendant that he lived ‘in the little houses by the side of the road’. And not only was it true, but it was, Nabokov reflected, the genesis of the novel.

Image © Carl Mydans