It was daylight in the loft, and cold. A room covered in demented silver paper, tacky and peeling. The light poured in and reflected myself back at me. From certain angles I had a halo of light, like an angel. From other angles I looked ridiculous. I was concerned by my own appearance. Anxious, ridiculous questions. I wore the shirt I’d shoplifted. I’d stuffed it in my bag and waited for my life to collapse. The stress and pressure had ruined my reasonable taste. I had only realised it was terrible when I put it on that morning. If you want to look good you have to fight for it in this ugly world, my mother always said. But I’d fought – and I still looked bad. The silver confirmed it for me. I had eaten a single grapefruit for breakfast which I couldn’t finish, sickened by the thought of Daniel’s mother’s mouth covered in the pale pink liquid. On the couch, some young people were stretching, yawning as if waking up, although it was the afternoon; their slim bodies spread out, their faces sleepy. A girl stood in the middle of the floor, unmoving, with a wide red mouth. I couldn’t hear any noise from outside, and the noises I could hear were slowed down, as if time itself had stood still. A shirtless man stood by a silver payphone, turning the dial aimlessly, seemingly no one on the other end.

A girl with the long legs of a dancer laughed and her laughter reverberated, seemed to reflect off the walls.

My presence here was pitiful, but it was too late. I kept walking. I couldn’t go back. At the far end of the room three girls who appeared miniature were gathered around desks: three drifters in a parking lot. As I approached them I braced myself for an onslaught of judgement, but the group barely acknowledged me. If it wasn’t for my silver reflection I wouldn’t have known I was there. I could tell one girl was slightly older than the others. She was tall, not made-up, tense. I still gravitated towards adult authority, and she seemed more like a grown-up than anyone else I’d seen in the building. She had a harried air of responsibility as if it was her job to make everyone else’s dinner, put them to bed. Her appearance was sober, comforting in a room where everyone else was a blur. She slouched in front of a typewriter, papers piled on either side of her. Several of the pages were covered in coffee stains, a pattern tirelessly repeating. I watched her experienced hands move across the keys.

‘Could you die from inhaling paint fumes in here?’ I asked.

‘Excuse me?’ she said. She didn’t look up.

She looked tired but that could have been an affectation. I glanced at her handwriting on the paper, an unhurried, bluntly organised print. She pressed the keys of her typewriter deliberately. There was the whisper of a click.

‘It just seems like something you should be concerned about.’

‘There’s worse things for your health,’ she said.

I picked up a paperclip from her desk. ‘Is that why you all go to the doctor? I’m Mae, by the way.’

‘Aren’t you funny?’ she said. ‘Where are you from? Hey Dolores, this little girl knows the doctor. Would you believe that?’

‘The doctor,’ a short-haired girl repeated. She sat a desk away and didn’t turn around. She and the third girl kept their fingers moving, their backs rigid, their attention far away. ‘The doctor, our hero.’

‘Hey, can I please have a cigarette?’ the older girl asked. For the first time she looked at me directly. ‘What did you do for the doctor then?’ She smiled. ‘What did you do to get him to be nice to you?’

‘Nothing,’ I said. I placed the cigarettes on the desk. I’d taken a pack of Mikey’s that morning. I’d tried to buy my own but I’d been overwhelmed by choice. I knew one of these brands would define who I was. There was very little I could do in life except get dressed, smoke the correct cigarettes. I slid them across to her. I wanted to act above the job. I wanted to act above explaining myself. But my body wouldn’t comply: it moved in jerks and starts as if each part was being helmed by a different captain. I cleared my throat. ‘He was impressed by me. He said this would be a good place for me to expand my horizons.’

She reached gracefully for the pack, tucked her little feet underneath her. A pair of Mary Janes lay abandoned beneath her desk. The sight of her bare feet startled me. ‘Aren’t you just fantastic,’ she laughed. ‘I’m glad the doctor stopped bragging about his sex life for long enough to spot your enormous potential.’ She put a cigarette in her mouth and lit up with a pale, bony hand. ‘My name is Anita. Do you have any skills or are you one of those girls that just hangs around?’

‘Girls that don’t work,’ Dolores supplied.

‘They come here,’ Anita said, ‘their parents pay their rent, they have these nice fucking dresses, they smell of hairspray, the perfume counters, they congratulate themselves for just getting up in the morning. I’m tired of listening to them.’

‘And they can’t answer the phone,’ Dolores said.

‘I’m tired of that smell,’ Anita said. ‘It’s very acrid. It’s air pollution.’

‘They don’t last long because Anita bullies them,’ Dolores said, laughing.

‘Something about them makes me want to bully. It’s the smell.’

I could hear Dolores and the third girl clacking hard on their keys, working efficiently and without passion, producing reams and reams of paper. There was something familiar and tranquil about the act.

‘I can type,’ I said. ‘I mean, I learnt in school.’ I said it as if it meant nothing to me. ‘I found a lot of what I learnt in school pointless, but that was useful, I guess.’

‘Be a secretary,’ Anita said. Her voice had a note of approval. ‘Or be a slob, go to bars all night.’

‘Those are not the only two options, Anita,’ Dolores said.

‘You look too young to have left school. Did you drop out?’ Anita asked.

‘Yes,’ I said, in what even I recognised as a hideously affected voice. ‘I dropped out because of external pressures.’ In a few, short minutes, I told them about the girls at school, the dance performance, the fit. The ostracism after what I thought was a simple remark. I was high on self-pity. I’d been trying to communicate a complicated feeling to these schoolgirls, one that they didn’t understand, and they hated me for it. A feeling about death, about God. I knew from the way that Anita and Dolores inclined their heads that they were listening, and it felt good to be around women who understood me. All my life, I’d been looking for that. I found the girls in school banal, and perhaps here was evidence that they were banal. I knew immediately that I could show these women who I was privately, underneath it all, and they would understand. The silver made us look like we were shining, like we were already in the future. I was running away with myself, embellishing, misrepresenting. I explained the part my former friend Maud had played – I highlighted her immense betrayal – but also how it didn’t matter because she was a phony who needed to grow up. I recognised her falseness. She was living in a fantasy. I said all of this with total, immovable conviction.

‘Stupid bitch,’ said Dolores, when I finished. Her voice was soft.

‘I can’t tolerate people like that anymore,’ Anita said firmly, ‘I just won’t tolerate them.’

‘High school girls can be hateful,’ said the third typist. Her face was fixed on the paper in her typewriter which was filling up. Her feet moved in time with her confident, impressive technique. She pulled out the page and placed it face-down on her pile. She reminded me of women I’d seen in adverts about housework – full of brisk, dead-eyed efficiency. Her hair was wrapped tightly in a bun. It resembled a coiled snake resting on her head. Her mouth was a thin, forbidding line.

‘Who’s the stupid bitch,’ Anita drawled, ‘the girl who had the fit or the one who made the fuss about it?’

‘I don’t know,’ Dolores said, already bored. ‘Both of them?’

‘People don’t like it when you talk about death,’ Anita said to me. ‘It’s not a big hit here either. You should know that.’

‘Or God for that matter,’ Dolores added.

‘I try not to hate those girls and Maud.’ I paused. ‘Even though they attempted to ruin my life,’ I added dramatically. ‘I forgive them.’

Anita started laughing, a great braying sound that didn’t suit her. ‘You are really something,’ she said. ‘Where did he find you? First of all, you can move to San Francisco if you plan on forgiving people. Around here we’re quite attached to our grudges. And don’t be pompous either, forgiving people pompously. That’s really ugly.’ She paused. ‘Speaking of ugliness, Edie is going bald.’

‘What does that mean?’ the quiet typist asked.

‘It means she’s losing her hair,’ Dolores said. She looked at me. ‘Don’t mind Anita. She has a limited mind underneath it all. Niceness horrifies her. Feel however you want about those girls.’

‘Limited?’ Anita said.

‘What really matters is how you make mistakes. Let’s give you a try.’ Dolores stood up and put her hand on my shoulder. She manoeuvred me in front of her chair. She was commanding – it reminded me of Daniel leading me into his bedroom. It was so easy to follow someone. I didn’t want to go home. I would have done whatever I was told. I took her seat.

‘Once we figure out how you make mistakes, we will know how productive you can be,’ Dolores said.

‘Do you have a CV?’ Anita asked. ‘Have you committed any crimes?’

‘How you make mistakes,’ Dolores explained. ‘If you’re fast, chances are you’re sloppy. You’re not thinking. If you’re too precise, you’re slow or excessively cautious. You won’t meet any deadlines. If you’re full of ego, you’re likely making errors you don’t even notice. If you’re shy on the page, that’s no good either. We give everyone a quick test to figure out their weaknesses. We’ve had girls here, girls that made a lot of blunders.’

‘Not that it really matters if you’ve committed crimes,’ Anita said.

‘It’s fine,’ the quiet typist said. ‘Everyone has weaknesses.’

The turn of her face, the lift of her long neck, like a little pony announcing itself. She reminded me of hundred things at once – a Christmas ornament of a child, the carving of a young girl on a soap, a face pressed to a store-front window.

‘Shelley is young too,’ Dolores said. ‘Your age.’

‘But at least she files her nails,’ Anita said, roughly grabbing my hand. ‘Gross.’ She took Shelley’s hand and placed it beside mine. The curve of her short nails, the softness of her palms. She was the cleanest person I’d ever seen. ‘Neat, very neat,’ Anita said. ‘Get an emery board. It will make you a better person. Do you have a boyfriend? We can get you one if you want. People are always breaking up around here. A cool guy. An asshole. Would you like that?’

‘Not particularly,’ I said.

‘Give it a rest, Anita,’ Dolores said. She took my hands and placed them on the keys. It was a newer model than I used in my classes, a typewriter that a hundred girls had known, trying to improve themselves, trying to improve their lives, with worn keys and broken springs. This machine was more impressive – the silver keys transformed it into something modern and powerful. I took a small breath, a whoosh of air. Dolores’s shirt was open and I could see her swaying breasts, but she was already sexless to me. Her flat practicality wasn’t appealing.

‘So,’ she said, ‘at the beginning it might seem like you’re not in control, that the typewriter is working independently of you, but you can control how you react to it, OK?’

I thought of the chair therapy Daniel had talked about, picturing the typewriter as Maud, screaming at it.

‘I won’t shout at it or anything,’ I said.

Dolores nodded politely.

‘If you make a mistake,’ Anita said, ‘you can start again patiently or you can tantrum and destroy everything. Be warned – if you throw tantrums no one will respect or like you. There’s enough people doing that here already.’ She was writing in a little grey notebook. ‘Or you could be like Shelley and be a perfectionist.’

Shelley’s smile in our direction. A row of uneven teeth.

‘You know, Anita,’ Dolores said, laughing, ‘I used to tell these girls that they would like you if they got to know you but I’m not even sure that’s true anymore.’ She handed me some pages, scraps of unimportant paper. ‘This is just practice, Mae. Don’t think you can’t ask me questions.’

Then I was alone. I felt nervous when my fingers first pressed the keys, as if I was embarking on an intimate relationship, which I suppose I was. I remembered my old typing teacher – an elderly woman with her hands clasped behind her back – strolling by, instructing, correcting. It felt good, after months of nothing, to be constructive, to have a purpose. The inside of the typewriter resembled an escalator, hitting the keys was like taking one step and then another and another. The radio played a simple, cheerful song at a low murmur. The clock hands moved, twisted round each other. The clock felt useless, as if it could spit out any time it liked. Around the room, people worked in pockets of concentration, groups of two or three, but the mood was languid. Two men came in and spread photographs on a long table. When they spoke to Anita, she turned silent and calm, her whole body angled towards them. The men were sucked into Levi’s that showed their hipbones, and one of them touched Anita’s cheek carelessly. She smiled back up at him, her face a beam of happiness. Everyone looked like they belonged in an advertisement. I tried not to watch the door. I worked quickly. I was faster than I expected to be. Nothing I typed was interesting or compelling, and it was easy too. From what I’d read I had expected it to be about art, scandal. I was already greedy for insight. The light changed. I was both relaxed and concentrated, and the typewriter moved in my hands like a toy. A man swept the floor in a strange back and forth way, as if he was engaging in an artistic method. ‘This place really is filthy,’ Anita announced to no one. She banged her typewriter like she wanted to win an argument. Shelley, on the other hand, looked like she and her typewriter were together, as if they were a couple. Where had I seen a look like that before? It was the way Daniel had looked at me on the train. Underneath the noise of the machines, I could hear the sighs of the couch as people sat down, as they removed their jackets, the creak of the floorboards as they moved across the room. I could hear Anita and Dolores gossiping. It was mostly real estate, who was living where. Who had ended things with who. The events were exciting but obscure, like a soap opera that kept flashing on and off. Someone was too good for someone else. Someone treated Anita poorly. Their voices were clear and intelligent. At one point, Anita took out two pills and put them in front of her. She swallowed them without water, and returned to her crossword puzzle. She filled in every small square. Shelley sucked on her fingers as if they were part of the machine and needed lubrication. For the last hour, I didn’t let my attention waver. I wanted to prove that I wasn’t slight or superficial. I was fixated on my typewriter, my mind moving like a ribbon. Here, no one could touch me. I could see everyone in my life moving out of sight, blurry, inconsequential. I watched a woman with long blonde hair get a haircut. She took the scissors to the ends herself. The strands hit the floor. She showed no emotion, as if the act was in service of some greater purpose. I knew the same transformation was available to me. I could become someone of my own invention. It was possible that I could kill the person I had been by doing the right work, by producing, by impressing these people. It didn’t occur to me that every girl in that room had the exact same ambition.

At the end of the day, Anita took my pages. I held on for a second and then let go. I was already possessive. ‘I’ll get back to you,’ she said. I wrote my number on a napkin and set it underneath her coffee cup. I was terrified they would lose my information.

Anita licked her lips and picked up her grey notebook. ‘So, last question, do you want to be an actress? Is that why you came here – the doctor told you you would get your big break? Do you want to be in movies? Do you want to have your picture taken? Are you lazy and selfish?’

‘Not really,’ I said. ‘I mean I probably am lazy and selfish but I don’t want to be an actress. As for the crimes, I stole this shirt.’ I pulled at the buttons. ‘So just normal crimes, regular ones. I was told I should look cool when I came in today.’

Anita pulled out the napkin and put it on top of her crossword. She wrote something on it. ‘Thanks Mae.’

I stood beside Shelley as we waited for the caged elevator. Neither of us spoke. It would have felt too sudden and strange after a day of being silent. She held a briefcase into which she had placed all her typewritten pages. The briefcase was solid and brown, with a gold clasp. It was a stuffy, uptight and pious object which I would have been embarrassed to be seen with. She was wearing a long green coat and high boots. I’d been stealing small glances at her all day and now she was in front of me, every part of her visible. Her face was vast and plain, and she had spread kohl inelegantly around her eyes. The music in the room had changed. Everything was in motion, and it felt shameful that Shelley and I had to leave. I glanced at her hands. They were smooth and, unlike my own, not covered in ink stains. Earlier I’d watched her replace her typewriter ribbon, the parts lying on her desk. There was something vaguely seedy about how I watched – as if I was seeing her get undressed without her permission. She didn’t have a single broken nail.

‘I scrub them,’ she said. ‘Every night, I use soap. Firstly gently, then aggressively.’ She mimed the action. ‘I’ve never lived like this before. I’ve never used so much soap.’

We stepped into the elevator and she pulled the cage across. She put her hand on my upper arm. ‘You won’t believe some of the stuff you’re going to hear in there.’

I felt the levels drop and thought of ropes tightening and loosening, the insides of every machine. ‘If I come back.’

‘You will,’ she said. ‘They care about people like you.’

‘Who are people like me?’

‘Remarkable people,’ she said. ‘Don’t be Anita’s slave. Don’t let her smoke all your cigarettes either. She’s unbelievably cheap. She can buy her own, OK?’

We emerged on to the street. It had rained, the pavements were a wet slick with the occasional puddle of light. ‘I spilled a cup of coffee on a paperback of hers and she had a fit. She’s very square, underneath it all. She hates anything she can’t control.’

I looked at her briefcase. ‘She only wants you to think she’s a monster,’ she continued. ‘I’ve been coming here for a month and I do a lot of the typing. You’ll like it here. You’ll be very comfortable. It won’t be like school. People will respect you.’

‘Well, I might like that,’ I said.

She laughed. ‘That story you told, the one about the dance performance, it made me feel . . .’ She struggled for the word.

‘Pity,’ I offered. ‘Desperation?’

‘Compassion.’ She had alert eyes and her features were pretty but disorienting, as if they were constantly being arranged and disarranged. ‘School is a long time ago now. Everything seems like a long time ago since I got here.’

I blinked and was reminded that we were on the street. The idea that the city was still here was preposterous – people walking briskly, people sitting in the back of cabs, scared of their attraction to each other, measuring out the distance between them, people making genuine and unforgivable mistakes on every street corner. ‘What brought you here?’ I asked.

‘I couldn’t use my abilities where I’m from.’

‘Typing?’

She smiled. ‘And listening. There’s not a single thing to listen to where I grew up. The life I would have had if I stayed there, it really filled me with terror. It made me feel like a freak. That’s the only way I can put it. So here seemed like a good idea. Everyone is on my level here.’ She stretched her arms excitedly over her head. ‘Hey,’ she said, ‘are you any good at buying things?’

‘I would be if I had any money. I think I’d be incredible at it.’

She let out a giggle. Her uneven teeth were appealing. ‘I need to buy a belt. I know the exact one I want. I’m going to look.’

I didn’t know if this was an invitation. It was easy to picture her in a department store, her overwhelming joy at even just being here, in this city, in this new life she’d chosen for herself. ‘Good luck,’ I said.

She nodded. ‘See you.’ She turned and walked away. When she was halfway down the street she shouted back, ‘Don’t let Anita smoke all your cigarettes, Mae. She’d smoke every last one if she got a chance.’

That night, I concentrated on my hands. I washed the ink off in the sink – the sink where I often watched Mikey, his huge back to me, shirtless, mid-shave. Staring into the mirror at his own reflection, the blades of his razor moving across his cheeks. His shaving always had an anticipatory atmosphere to it: he had a job interview, he was giving a poetry reading, he was meeting a unique personality. A look of almost violent concentration as the razor met his face. I took a nail file from my bag. I’d bought it on my way home. In the line, a mother in front of me was telling her daughter that she was getting fat. ‘I don’t care,’ the daughter said, ‘that’s just the way it is.’ Her sullen, bored attitude reminded me of the typists. Young people everywhere were treating adults with bare contempt. Girls with ugly haircuts smiled condescendingly. They were trying out new facial expressions that their parents didn’t understand. The adults weren’t in on the joke at all anymore, and the thought made me happy. In its plastic case, the file resembled a tiny knife. I wondered if I could do damage with it. The ripping plastic sounded like a secret being revealed. As my nails became neat moons, my own life seemed to recede into the distance. I could pull the whole apartment apart – the damp, furry carpet, the cream walls – and reassemble it, like I’d watched Shelley do with the typewriter. I examined my hands for so long they seemed to blur and disappear. I thought about what they could produce that would separate me from thousands of other girls, and I waited for Anita to call.

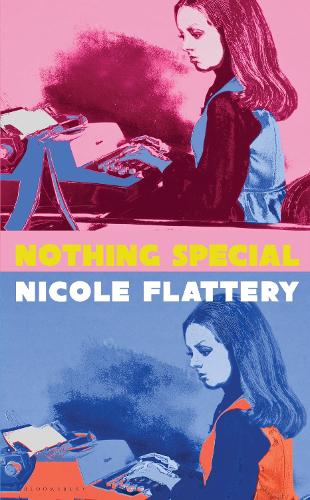

Image © Cathy Labuduk