Kipling has long been a controversial figure. George Orwell once described him as ‘morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting’; earlier this year protesting students at Manchester University defaced a text of his poem ‘If’ that had been newly painted on the wall of their students’ union. Yet in 1995 listeners to BBC Radio 4 voted ‘If’ their favourite poem. And two lines from ‘If’ remain in place on the wall of the players’ entrance to Wimbledon’s Centre Court.

Much about Kipling is paradoxical. He has been called – not without reason – a racist. Yet his novel Kim shows a profound love of India and a deeply sympathetic understanding of Tibetan Buddhism. And here is one of Kipling’s two-liners from ‘Epitaphs of the War (1914-18):

HINDU SEPOY IN FRANCE

This man in his own country prayed we know not to what Powers.

We pray them to reward him for his bravery in ours.

Much has been written recently about our shameful failure to remember the many Indian soldiers who were killed in the First World War. Kipling knew better. But how many of us would have imagined him declaring his readiness to pray to Hindu gods on behalf of an Indian soldier for whose courage he clearly felt grateful?

We know the war prepared

On every peaceful home,

We know the hells declared

For such as serve not Rome.

Kipling was sometimes strident, and sometimes mistaken. Nevertheless, we are impoverishing ourselves if we dismiss him as a drum-beating imperialist. In his best work his imagination ran far deeper. Though a non-combatant, he is – along with Edward Thomas and Wilfred Owen – one of the greatest of our war poets. His poem about the execution of a deserter, also from ‘Epitaphs of the War’, is remarkable. Few poets have written about cowardice with such compassion and understanding:

THE COWARD

I could not look on death, which being known,

Men led me to him, blindfold and alone.

Kipling-haters see him as representative of all they despise about the British Establishment, yet he always saw himself as an outsider. He refused the invitation to become Poet Laureate and twice declined a knighthood; according to his wife, ‘he felt he could do his work better without it’. And few poets have written more devastating attacks on the Establishment. Here, for example, is one of the very few of his epitaphs where he resolutely refuses to show even a hint of compassion or forgiveness.

A DEAD STATESMAN

I could not dig: I dared not rob:

Therefore I lied to please the mob.

Now all my lies are proved untrue

And I must face the men I slew.

What tale shall serve me here among

Mine angry and defrauded young?

Kipling’s most notorious poems now seem dated; ‘A Dead Statesman’, however, sounds startlingly contemporary.

Amit Chaudhuri, of the University of East Anglia, has referred to Kipling as ‘a compelling and very, very gifted writer’ who ‘clearly had racist prejudices’. He continues, ‘There are great blind spots in Kipling and the blind spots are all the more curious and regrettable because they occur in a writer who was extraordinarily observant, and acute in his observations.’ Chaudhuri also suggests that we should rethink our desire for writers to be perfect.

Kipling is clearly no saint. But his vivid sympathy for ordinary soldiers is wonderfully conveyed in his ‘cockney’ poems, his delighted understanding and respect for children in his children’s stories, and his racial prejudices are repeatedly contradicted when, as in Kim, his imagination is fully engaged.

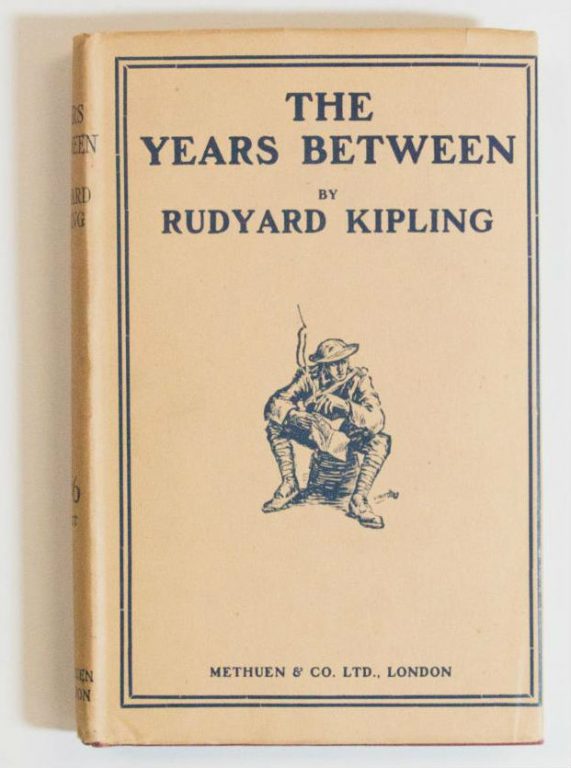

If you wish to reconsider your attitude to Kipling, the ‘Epitaphs of the War’ may be the best place to start. If you can’t find a copy of The Years Between, these epitaphs are included in most more recent selections. Stories and Poems (OUP) provides excellent notes. Selected Poetry (Penguin Poetry Library, now out of print) includes an interesting introduction by Craig Raine, who makes a strong case for Kipling not as the poet of empire, but as the poet of the underdog.