Out of Body Experience

I hear little clicks when I hike through the Dandenong Ranges. It could be the leeches, sticking and unsticking. Leeches doing as I was warned they would, dropping through the canopy. Or: the sound might be in my head alone. The clicking is like the cap on a childproof bottle being twisted and twisted. It is like the click of a rollercoaster, starting off.

The mood is medieval, which is the historical style of all rainforest gullies regardless of their specific geography. Tree-stumps as headstones, their fallen progenitors gone dankly to rafts of grit underground. Anaerobic spools of hyphae burst out as fungi, gapes of baby-teeth. Sometimes an earthstar, if kicked, releases a column of spores that walks on ahead – a child-ghost paddled by ferns. The smell is haemal. Wet iron. Grunge and ferment in ruts. A scrape, a skid; the ditherings of nocturnal theatre on the path. Crunched bones in scat, there, the mud rucked and feathered. Dead dust in the air. And leeches. Leeches teeming, flocking, unseen. Intuit them everywhere, in the trees and also the streams, the brushwood, the bracken. Leeches moving in unison. Like a monster hacked and partitioned. Drawing itself back together commanded by my mammalian warmth and scent, crawling through the shade and quickening its danse macabre. I think I hear the clicks. No, it is not my jaw popping. I pull my socks up against the leeches.

Two leeches, when they mate, press together like the lips of one mouth. A kissless kiss in leaf litter, or a squeezing moue of dissatisfaction. Either way, something expressive in it. How like an aperture, an opening – if parted, to what (and how far, how dark)? Lips, olive-black, on the forest floor. Each leech has a pair of hearts. Two leeches conjoin their sensitive anterior suckers and clamp, lateral. Their pout pulses, contracts and crimps, it softens, melts, drips. The mucus-covered skin of a leech seems to want to dissolve any surface it encounters, so when leech aligns with leech the border between the pair, imagine it, turns tender, then liquid, and then – doesn’t it? – disappear. What part of a leech bites; is it the part that couples?

After seeing leeches splayed in little doublets and crucifixes on the moss, elsewhere write down two kisses to close your correspondence: XX. Sex chromosome, but not one of leeches. How far does the hand get before the thought occurs what was I crossing out here?

Leeches are hermaphrodites. But not all at once. They begin life with two sets of nascent genitalia, then their sex organs mature sequentially. First male, they transition to being female. That moment of switching: the female consumes the inward male. Or perhaps this process is less like overpowering, less like predation – a gentle subsidence, a giving way.

Why was the first impulse, an unconscious impulse, to subtraction – to figure those written kisses the work of striking out? X too, designates multiplication. X brings to mind the XX-ing of stitches, of suturing together, the mending of what has been painfully opened. I feel like something about this has to do with leeches writhing in the Dandenongs. The fine line between healing and harming, perhaps, and its transgression. (XXX on a bottle: medicine, liquor or poison?) Watching the leeches, what was confusing – and, in turns, wondrous – was whether they were sucking each other up, cohering, turning inside out, or reproducing. Making more leeches or less? I had wanted so much to touch them, to intercede in their pinching. But I didn’t, knowing it dangerous. Leeches get on you and they can shoot up a nostril or slip beneath an eyelid. Then it’s real damage.

Freud had a patient once, a woman of thirty, he writes ‘most attractive and handsome’. This woman came to see the famous psychoanalyst after she heard a clicking or ticking she could not explain. The story she told went like this: she had a man, a new lover, and having gone with him to his ‘bachelor room’ in the daytime, having amorously undressed there on the sofa, she was alarmed to hear the click of a camera coming from the direction of his writing desk.

She later came to believe the man had concealed a conspirator (or conspirators) behind the curtain beyond the desk, persons he had arranged to take photographs of her naked in his private quarters. The woman heard the ticking, the shutter, and transformed her lover into a persecutor. She fled (without pulling back the curtain) and set her mind to sending him long, reproachful letters. The man refuted the accusation – there was no such voyeur! But the idea took hold of her until she felt it was always upon her: an obsession. Who was the obscene photographer in league with her lover? Was that person doubly her admirer, or was he ashamed? Ashamed for her, she worried. Did she appear vulgar in the shot? Parted, on display? Did her lover mean to share her with another, or others; or did he want to arrest her image for his own possessive enjoyment, to keep her his, in his drawer or interleaved in a folio. (Perhaps together with photos of other women.)

In Freud’s account the woman doesn’t put a word to the fear of having been, or having been the subject of, the lecherous. As in lecherous (adj.): showing offensive sexual desire. As of a lecher, a man given to lewdness, debauchery, and, how Webster’s puts it: a glutton, a libertine, a parasite. The feminine form is lechiere or lickestre, literally ‘lickster’ (nativized as ‘lickerish’) – ‘female who licks’. Lascivious. Only the masculine lecher persists with its negative connotation in English. Disquieting lust, desire misplaced and excessive. The lecher is a male looker in the modern sense, the upskirter, a perve, but also a consumer, a copper of feels, a licker of aura, a sucker, a leech.

Freud’s diagnosis transfigures the photographer behind the bedroom curtain into an hallucination: not, in fact, a photographer or a man, but a woman watcher, a surrogate for his patient’s mother. The gender-morphing individual imagined there, the doctor claims, was no more than an externalisation of the woman’s suppressed lesbianism.

This much we can soon do away with (and exasperatedly). But what of the sound, the click? A sensation not a sound, reports Freud, an internal noise. He elaborates. The patient experienced her physical responses as audible. Why? She had feelings she could not lay claim to, bodily; sensations of arousal, being triangulated by her envisioned voyeur and her male lover. The click she heard was ‘the sensation of a knock or beat in her clitoris’, writes Freud. The click came from inside her. The camera was inside her. The camera was her clitoris.

What Freud hit upon was this: there is nothing more introspective than exhibitionism.

But I have often wondered about the significance of the writing desk in this symptomology. That the sound emanated from the direction of the desk seems not an inconsequential detail. The desk, that hard, cool surface on which the woman’s lover wrote love letters to her, signing and sealing those letters XX – say he must have, either side of the quarrel; if his goal was to entice or appease her. (One X for the self that composes a letter, the other X for the self that wants what it wants on a sofa – the distance between the difference might be short, or long).

Only, perhaps he initialled each letter with only one X in lieu of his real name. The kind of X that is both an erasure (X is anyone’s anonymous mark on correspondence intercepted) and simultaneously, a glyph of intense intimacy. Whose desires unfurled from the tight axis of that single X? The woman was expected to know, her suitor imagining himself singular, the only X in her letterbox.

Write an X with a pen on paper and the dash–dash of it can also feel, and sound, like a clicking. Try it now yourself. Then stand on the other side of the room for a minute, and listen.

The same psychological anguish of the photographer behind the curtain, that kind of knowing and not-knowing, is the weapon of leeches. I have been bitten by two leeches, two leeches that I saw. One as a teen, one last year. Many more I have imagined, phantom leeches that have me scanning my skin with a compact mirror on return from the forest. The first leech sucked in my armpit after a swim in an ungazetted creek in Walpole, Western Australia. Cold water, the colour of Coca-Cola. If you can stand it – and I do mean, existentially – nothing about a leech bite hurts. You are not supposed to pluck a leech off your skin midway through its meal, or salt or burn it with a cigarette, because that might prompt the leech to regurgitate the noxious fluid from its stomach which causes an infection. It’s better to wait it out. The leech in Walpole grew fat and tight as a fig, then fell off. It slid into the understory. I pondered longingly the leech. Gone, with my blood inside it, plugging me into the riverbank. I told no one about it, fearing disgust. Where does a body start and end? I asked myself this question often as a teen, sometimes the answers were about pleasure, and sometimes they were about paranoia.

The second leech is private.

Well, okay. The second leech was tiny. It prowled off the shaggy trunk of a tree fern I was leant back against, and fastened itself on the side of my bare hip. I struck it off with a knuckle before the word ‘leech’ had even risen to my tongue, I think before I knew that it was a leech (something evolutionary in the horror of recognizing it). Then I asked the man I was with to stop, and I saw how the lipstick I had slicked on had earlier left a red insignia, like two burning leeches laid side by side, on his chest. The light was gasping. I wanted him to check me all over for other leeches; the leeches I couldn’t feel, but which I was then convinced were everywhere on us like the eyes of the hikers I had, moments before, erotically conjured – or who were really there – watching us from the distant path above, cameras swinging from their necks and lusty heat on their breath.

Now I do and do not hear little clicks. Perhaps it is grasshoppers, or ripe seedpods snapping. Perhaps it is the felt anticipation of the letter I mean to write and am mentally composing. Or perhaps it is that species of bird that breaks snail-shells by tapping them, once, twice, on a stone. A leech alone makes no noise, for it is only one parenthesis and half a mouth, hanging always open, hungry for more.

Telepathy

Early in Lauren Groff’s novel Fates and Furies, the protagonist Mathilde tells the man she has newly married about her childhood in the Pennsylvanian countryside, so isolated and bleak, so lonely, she let a leech live on her inner thigh for a week just to have an ally and a secret.

Years later her husband, a playwright, recounts the story as though it were his own experience – the leech placed snuggly on his thigh, in his youth, in Florida. This re-latching of the leech occurs during a radio interview. The playwright offers the anecdote as a founding myth of his creative life. How friendless those days were, unsupervised in the miasmic swamp – his affection so lost for a proper target it adhered even to the repellant, oozing leech. The interviewer is shocked. Then soft-hearted.

After the broadcast Mathilde confronts her husband. She accuses him of stealing the episode to dramatize his boyhood. ‘My loneliness,’ she says, stonily, ‘not yours’. But the playwright insists on the memory, how emphatically it registers in his body. (‘He could feel the hot mud on his legs, the horror dissolving to a kind of tenderness when he found the small black leech’). Mathilde grows outraged, as I certainly would too. How could her husband let what happened to her, become something that happened to him? For how long has he been secreting the leech into his own personal history? ‘It’s not that you stole my story,’ she rails: ‘you stole my friend.’

Can a leech be a friend? Is it worse to steal a story or a friend?

Nestled companion, the girl-Mathilde welcomed the leech because its presence drained her loneliness in addition to her blood. But, being unlike anything we call ‘pet’, being unfriendly, faceless and parasitic, the leech only serves to amplify her solitude. In Pennsylvania no one cares for the young Mathilde enough to check her over for leeches. ‘Leech’ is both the animate shape of her emotional abandonment (a way to place that pain outside her, to see the agency of her sadness) and, at the same time, the leech is a fruiting reminder of her ongoing neglect.

Its placement on her body says more still. In the crease of Mathilde’s inner thigh, the leech’s suction – ‘so close to what mattered,’ it ‘thrilled her’ – both defends Mathilde from being touched, and underscores how untouched she is, how much she desires.

Freudian, the yonic brushstroke of the leech in Fates and Furies, swelling gently with blood. A kind of autoeroticism deferred through an animal. The nourishing wound. To be fed on by leeches is to be terribly alone and intimately accompanied.

Groff depicts the thievery of Mathilde’s story by her playwright husband as brutish and blundering. Doubly so for his withering defence when it dawns on him that his wife has remembered it rightly, the leech belongs in Mathilde’s tale of origin. ‘To be fair, it was a leech,’ the playwright says, dismissively. ‘A story about a leech’. So two times, he leaches off Mathilde’s tale! Her playwright husband draws the emotion out of the leech to furnish his own public myth of provenance (he takes its loneliness, Mathilde’s loneliness, and uses it). Then, in suggesting the leech had no real symbolic charge – that her leech story is a trifling one – he uses the leech again to remind Mathilde she is alone even within marriage, having failed to transmit the true significance of the leech to him such that he would not think to touch it, to appropriate it as his own.

The playwright’s mnemonic vampirism ends in blood on the sheets. In the closing minutes of the radio interview he claims to have rolled onto his leech in sleep, and exploded it (premonition of menstruation or a vile wedding night). ‘There was so much blood that he felt guilty as if he’d murdered a person’. And he has, hasn’t he? Murdered his wife’s girlhood by absorbing her memories, her wounds, into his body, and metastasizing them there as his own?

Groff knows, as we do too, leeches are primordial, saturnine, druidic, powerful and chaotic creatures. A leech can fill with feeling, tapping the vein of a host. Leeches are hexes, wishes, incantations. As per Proverbs 30.15: ‘The leech has two daughters. “Give! Give!” they cry.’ Give, give. The leech is acquisitive. The leech is fecund.

But there remains space in me still, for a narrow kind of empathy with the character of the playwright. Something about talking of leeches makes you sense leeches on you. Twitchy. I feel for you, people will say in pity sometimes, but how is it meant? How does a feeling migrate between us, and where does it lodge? A leech story moves not just in the mind, but in the body. This is its magic. Write about leeches, tell stories of leeches, and you might begin to feel the touch-point of a leech on your own skin, a trail of wetness, a prickling, an itch. There: behind your ear, on the underside of your knee. Listen to leech confessions or read them and the residue that lingers is more sensation than information. A shudder. One real leech begets many more imaginary ones.

Scrying

I said before I had been bitten by two leeches; one I encountered as a teenager, the other last year. Incisions made by leeches do not look like small, darned crosses. If you examine them closely, you will notice such bite marks are Y-shaped. The skin darkens around the wound so that the scar is sometimes compared to the logo of Mercedes Benz: a circle with a three-pronged Y-star in the middle of it. But the leeches that got onto me were not the earliest I can remember. The first leech I took (allured, bewitched, mesmerized) from the waters of Herdsman Lake.

In my schooldays our classrooms were not air-conditioned for the summer heat. So during the crucible hours of windless weather in February the teachers sometimes instructed us to empty our desk-trays and troop out, as guided, across the roadway to a nearby shady wetland – called Herdsman. Here lay the last of a series of linked lakes that once marbled the coastal plain. Swamps really. Most had been dredged in groundwork for the suburbs, leaving behind sandy foundations that darkly softened. Sometimes a chthonic stream would rise to recoup a post office or the quadrangle of the local college, keeling the bitumen inward as if something heavy had alighted and taken off again during the night. Herdsman was the only above-ground freshwater lake maintained as a nature reserve.

Sweat-damp hair lacquered our foreheads on these excursions. Between the fluffing bulrushes our teachers filled each child’s plastic tray with a slop of lake water. Heat meant the lake was stacked with life, evaporation tightening on gram after gram of microfauna. Invertebrates idled in the nascent phase of their lifecycle, sensing the sunstruck air over the lake’s meniscus to be intolerable.

Then we lay on our bellies under the fragmented shade of Western Australian peppermint trees, prodding the settle with plastic spoons. Aquatic beetles, waterboatmen, shot like comets across the water in our trays. Chartreuse weed ticked with damsel- and dragonfly larvae – shabby offspring of gemstone parents, strafing the mirror of the lake beyond. If you were lucky you’d observe predators stalk quarry not bigger than punctuation. Jerking nymphs. Streaming things. Mosquito pupa, I haven’t yet forgotten, are known as tumblers. Tadpoles joggled the water striders trampling above. In the silt below scribbled tiny, glassine snails, their inscrutable cursive akin to the handwriting of some decorous but laudanum-abusing ancestor.

We were the looming gods or satellites of these worlds. It pleased us to scoop things out and study them mid-air, asking for their names.

Whole afternoons could pass this way – scored by the cacophonous zip-zipping of cicadas, chewing on the toggle of a hat-strap. Melon vines corkscrewed through the sedges, malingerers from failed 1930s market gardens. That the lake glistened with iridescent runoff from the nearby light industrial district did not, to us, make it any less wild. Quintessential, befouled, semi-urban Australian reservoir: we had it from older kids that the heart of the wetland was bunged with stolen shopping trolleys. Also rumoured to be deposited there was a beautiful statue; a goddess called ‘Plenty and Peace’ pulled down from the crest of a city bank, her Grecian features greened by verdigris and the crapping of ducks.

The Indigenous cosmologies and histories that configure the lake went unobserved on these trips, except that our teachers sometimes repeated the claim: once people met up here to eat gilgies and yabbies, which are crustaceans. Who those people were, we weren’t then told. Today this place is sometimes called Njookenbooro, though that name extends to the perimeter of a disappeared wetland of which the lake is only a remnant. The dominion of the place ‘Njookenbooro’ persists even as the territory beneath it has turned mostly to asphalt. People who know say you are in Njookenbooro too when you cross the surrounding apron of car parks and roads. Standing inside the loud factories, warehouses, printeries and auto-body shops that abut the lake, you stand still in the uncontracted sovereignty of Njookenbooro.

This hot hour I am drawn back into by the leech; a traction, little black hole. Pushpin for memory. The leech, thrashing at one corner of my tray, was an instant spot of fascination. A jet-black sash this one; flat and pinched at either end in the style of a kimono’s obi. You might apply the label ‘worm’ if not for its gyroscopic locomotion. The leech fluttered like a tiny, deathly gymnast’s ribbon. It climbed the sides and jabbed up into the air. At odds with all the other animalcules in the tray, the leech seemed to know it had been trapped. Know, and resist.

I dipped my disposable spoon and caught it in a pool. I brought it nearer to my face for inspection. The leech ceased its frenetic coiling and stretched from the lake water to meet me. A glossy nib sweeping to and fro in the air, drawn thin as a speedometer needle. Here, the first animal, not tame, to address itself affectionately to my existence. In gesture, to seek to touch me.

The teacher smacked the spoon right out of my hand. She stamped all over the ground where it fell. Anything there, organic or plastic, ended up crushed to smithereens.

Panopticon

Perhaps what makes a leech so unsettling is the way it implies that something inside you has become excessive, or could. What is that? Morbidity. Deathliness in life. Sickness. Or sentiment. The swallowed weather of obsessive feelings and intrusive thoughts. (This ‘unfortunate morbid idea’, the man who seduced Freud’s patient called her delusion.) Fallen on thick fabric a drip of blood branches into a cross-shaped stain – tiny observance. A leech signals a body unfastened and opening to sites beyond itself. A kind of catharsis or purge, the impulse to eject what has become too much to hold. Seen this way, leeches are avatars for how florid our inner selves might become, possessed by repetitive imaginings and circulating imbalances in the blood.

A leech bodes this: you will, sooner or later, overflow yourself. You will open, a little slit, like a flower. Or be opened.

The notion of the purgative leech tracks back to medicine, or so I’ve discovered. I have been reading about leeches (finding, as yet, no evidence for a leech’s vocal chords). In early modern Europe leeches were devices not of horror, but hygiene. Leeches were so extensively collected for therapeutic bloodletting, it turns out, they became endangered in the wild. By the late 1800s the exorbitant price of each new leech led doctors to snip the tips off those in storage so that the costly animals could be deployed more or less constantly, feeding without satiation when their meals passed right through them. (A leech will otherwise survive off a thimble-full of sucked blood for a year.) Physicians and pharmacists displayed their captive leeches in ornate ceramic jars, gilded gold and stippled with air holes. Many of these containers that survive today are priceless antiques. There are some on display in museums in London. I have seen them. They are empty, of course, of living leeches.

Commercial leech-gatherers of the era went to perilous lengths to draw from dwindling populations and fill these jars for the supply of surgeries and hospitals. They waded, mostly naked, through quagmires and fens to attract leeches to their legs and torsos, collecting also, for their trouble, bacterial, blood-borne diseases (a leech conducts the outside in, and too the inside out). The leech-gatherers depleted wild places of leeches, all the while being drained themselves. They ended their days etiolated and hideously inflamed, all over, from the bites. Hirudo medicinalis – the clinical leech – was declared extinct in the British Isles in 1910 (too soon: the species in fact clung on in isolated marshes and a few turbid garden ponds).

As the national supply of free-roaming leeches in the UK begun to taper off, international trade grew to be big business. Wetlands all over Europe were repurposed as leecheries to varying success; in Sweden, Prussia and Hungary, in Algiers and Marseilles. Leeches were imported from places as far afield as Egypt and Australia (the fat Murray leech from the banks of the Murray River was much prized). When conveyed by sea, these leeches were fed on oxblood and stored in ‘portable swamps’, earthenware basins containing clods of damp soil – though often the leeches escaped to overrun the crew. There was leech piracy, leech poaching. The Norwegians raided the Swedes for leeches. The Germans smuggled from the Russians.

The part of this history that stays with me most of all relates to a specific leech farm, run in France in the early nineteenth century. What a leech farm in this period looks like is: a series of shallow, flatland pools through which horses, cows and donkeys cut with knives are daily dragged alive. (A leech may make no audible noise, but surely the horses screamed.) One enterprising leechery owner M. Borne – his first name lost to time – oversaw a French farm that was often pillaged by leech thieves at night. So he built a lighthouse at the center of the farm and staffed it with armed guards.

I think about that tower, since destroyed or cracked down by the wind, and its searchlight circling over the ponds. The men on watch with their guns, whose silhouettes paced the lantern room and clutched the icy, outdoor railing. Those men waiting, adjusting quietly the weight of their rifles, alert for the footfall of trespassing leech pickers. Was there ever a more gothic project? Standing watch over these tiny dismantlers meant being surrounded, being psychically swarmed, even as the guards sought to ward off the human, proprietary threat that ducked the sweeping beam of the lighthouse. Did they too, look each other over for leeches acquired on the walk across the leechery to their, most nocturnal, work?

Haruspex

Leeches do not do the salvage-work of deconstructing the dead as fungi and maggots do; leeches eat from the living. To be consumed by leeches is to be vital, to be animate, though it is also to be reminded you are something else’s prey, and therefore porous and mortal. A leech is a memento mori even as it beats with a pulse that sounds, to me, like this: alive, alive, alive, still alive.

On the borders of a tropical Vietnamese rainforest biologists are cutting open leeches to look for evidence of animals no one has never seen before. Leeches there can carry the blood proof of cryptic and rare mammals, throbbing somewhere in the forest’s thickened heart. Ferret-badgers, shy striped rabbits, and a creature called a Truong Son muntjac – a species of deer not bigger than a cat, the colour of which is unclear because there has only ever been one blurred photograph of it, taken by a motion-tripped camera. DNA in the leeches testifies both to the existence of these strange beasts, and how imperilled their populations are, sectioned into ever-shrinking patches of habitat. It may be that the tiny muntjac deer disappears long before the scientists ever get to see it again.

Clairvoyance

If leeches sing as birds do, or if they click in the way of a lens shutter, then it seems most humans don’t possess ears fit to hear them clearly. Movement, you might say, is the only vocabulary that transmits between our species. How leeches inch, how leeches squirl and knot: if you’ve seen them, you know there’s nothing wormy about it despite the fact that leeches technically are annelids. The cogs of caterpillars rarely move this way either, preferring to ripple across a leaf. Earthworms corkscrew into the ground with a pleasing, muscular torsion. You tell a leech apart by its dreadful, uncanny motility.

First the O of its sucker (no larger than the O appearing here) stretches out, seeming to sniff the air. Then – when the sucker reaches and lands on whatever surface the leech intends to trample over – the leech draws up its rear, contracting itself into an overturned U, a loop. This is how a leech moves if it is unhurried. Vowel over vowel. The way a slinky uncoils and stacks, uncoils and stacks. I have never met a person who wasn’t unnerved by the kinking motion of a leech.

What intelligible compulsions propel a leech forward through the fabric of the universe? What are their susceptibilities to polarities of light, odour, vibration, appetite? Are they ever moved by empathy for other leeches? Impossible to tune into the alien, inner lives of leeches, though what is inside a leech might be the most intimate thing: us. Blood.

Knowing this I was not, in fact, surprised to learn that there was a time when a leech was a kind of technology for foretelling the future. Or at least, that part of the future that arrives in the sky. That leeches were supposed to augur the weather seems entirely consistent with their talismanic charge. In 1850 a British doctor, George Merryweather, became convinced that the medicinal leeches housed at his Whitby practice were capable of prophesizing atmospheric disturbances – storms – ‘not by articular utterance of oracular notices,’ he wrote, ‘but by a variety of gesticulations’. Merryweather. His very name portentous. During quiet moments in his surgery, the leeches’ activity distracted the doctor. Notwithstanding that, when not snibbed onto his patients, all his leeches were stored in separate containers, they appeared choreographed. The maneuvering of Merryweather’s remedial leeches, he suspected, betrayed some eloquent, decipherable sensitivity. Over time the doctor came to believe leeches gave advance notification of bad weather by ascending in their containers. The leeches weren’t merely medical instruments, they were meteorological ones. Leeches were how the weather was notated.

George Merryweather, like Mathilde in Fates and Furies, held leeches could be his friends. ‘My little comrades,’ he called them. ‘Capable of affection,’ his ‘jury of philosophical counselors’. He put each leech in a glass jar, as opposed to a ceramic one, in order that they should see one another and better ‘endure the affliction of solitary confinement’ (though too, Merryweather thought leeches, being hermaphrodites, made them ‘capable of living alone’: a cruel mistake). The leeches were his scientific collaborators, but also, his devotees. ‘They never attempt to bite me,’ he claimed, ‘but some of them have, over and over again, thrown themselves into graceful undulations when I have approached them; I suppose as an expression of their being glad to see me’. And maybe they were – the doctor was their means of getting fed.

Merryweather’s hypothesis about the rain-dance of the leeches was this: climbing the sides of their apothecary jars to cling beneath the lids and stoppers, the writhing leeches were drawn by ‘ganglionic instincts’ to rising ions of caloric electromagnetism in skies that were, as yet, untroubled by clouds. The leeches’ agitations, he inferred, owed to the urgings of all suctoria to siphon radiation from ‘the vast aerial ocean’, chasing voltaic currents plucked upwards toward outer space in advance of rain. Leeches were electrically unstable: this was what made them sensitive to storms. In this way, they were connected to the upper atmosphere, far up to the stars. Merryweather envisaged a leech as a biotic battery, polarized to chase after, and concentrate, free-roaming energy from the air, then shinny it back down into the earth. In the rising action of the hirudo medicinalis, his stored companions or surgical tools, Merryweather identified kinetic potential to animate a new invention and signal advancing weather systems insensate to humans. Were he able to harness and amplify the leeches’ meteorological body language, Merryweather would possess the means to anticipate the worst squall or the lightest rain. He would palpitate animal senses to foretell the weather. He would build, in short, a leech barometer.

The Tempest Prognosticator

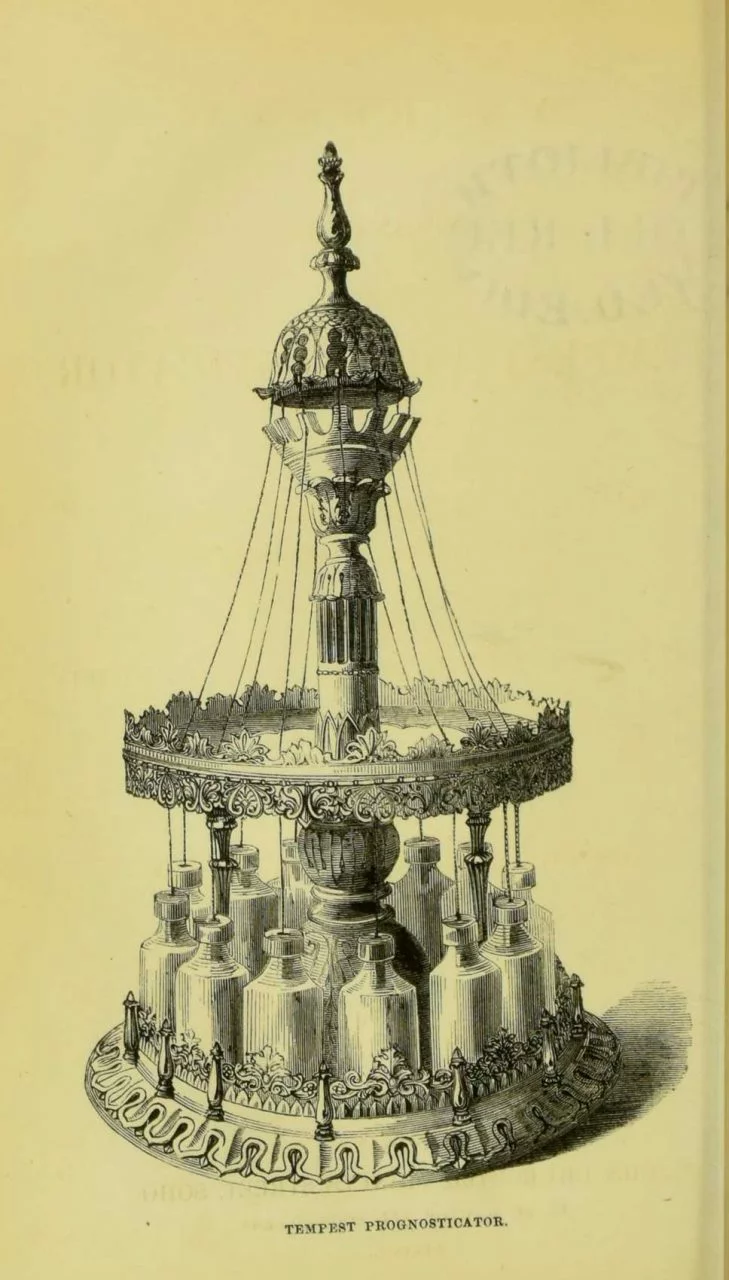

Merryweather’s invention is lost or destroyed. At least three replicas have been constructed and still exist: two in American collections, and one on display in North Yorkshire. He called it: The Tempest Prognosticator or The Atmospheric Electromagnetic Telegraph Conducted by Animal Instinct. Being not in view of a surviving model, let us now together visualize this tempest prognosticator – animal appliance, small sanatorium of leech premonition.

Envision a fairground carousel the size of a record player. It’s made of brass, silver and French-polished mahogany. The rotunda is ornate and needles upwards into a spire that is three-feet six-inches high, like a miniature lighthouse. Atop the spire is a golden dome. The dome is Mughal in design and faceted, ‘crowned with the germ of British oak’. From the shining dome extend golden chains like necklaces, twelve chains, which are threaded down out over the filigree cresting (a disc-shaped eave above the device’s main platform) in the same way a peaked canopy stretches from the spindle of a carousel to its perimeter, shading the riders. The chains drop from the cresting into the corks of twelve bottles, positioned in place of painted ponies. Inside each bottle is a leech, glistening like a lump of jam. A few drops of rainwater make a wet film along the bottom of the glass. Leeches desiccate in ordinary air.

Merryweather’s drawing of the Tempest Prognosticator, 1851

Examined from a nearer aspect it is possible to see that inside the neck of every individual bottle is a piece of whalebone, placed laterally like a beam and hitched to a piece of chain, which is loosely threaded through a cored hole in the middle of the cork. There is surplus chain, it dangles into the bottle an inch or so. Here is the prognosticator’s paramount mechanism: if the leech in the bottle attempts to dislodge the stopper, or huddle beneath it, the whalebone – which is only gently balanced in the bottle’s neck – is knocked, falls out, and the chain is tugged. The shaft in the cork is too narrow for the leech to escape, but allows the chain to run through it. To keep the inside surface of the bottlenecks clean and smooth, Merryweather painted them with varnish – the resinous yield of a kind of beetle that treacles and swarms when brooding. Merryweather cleaned the bottles with a tiny camel-hair brush made, despite its dromedary brand name, from fur off a squirrel or rabbit. Animalian componentry.

What is hidden from sight is the bell contained within the pinnacling dome to which the chains attach. The dome is a belfry and at the other end of each chain is a small hammer. So the movement of the leeches when they climb into the bottlenecks – tugged, supposedly, by gathering clouds – tweaks on tethers that cause the hammers to sound the bell, transforming their gesticulation into an ‘oracular notice’; the ‘tinkling tocsin’ of inclement weather.

The doctor petitioned to unveil the tempest prognosticator at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park’s Crystal Palace – that immense, plate-glass showcase of empire, new technology and importuned artifacts. In homage (and openly to improve his invention’s chance of being favoured by the curators) Merryweather designed the instrument to mirror the northern Indian influences in the Crystal Palace’s architecture. He fashioned the prognosticator as a mise en abyme, a miniature copy, of the prismatic grandeur of the Crystal Palace. His aim was the widespread adoption of the prognosticator as a tribute to the genius of the Crystal Palace, and a gauge of the ‘prodigies and convulsions of nature’. Merryweather saw many prognosticators, activated by innumerous leeches, stationed up and down the British coast. The essential mechanism, he proposed, could be linked to major infrastructure. Merryweather contemplated the re-rigging of St Paul’s Cathedral in order that his leeches might ring the great bells and warn the whole of London of bad weather closing in.

So certain was George Merryweather of his discovery’s unparalleled significance he scripted an epitaph for his own headstone extolling a lifetime’s guardianship of the world’s mariners, protected from the terror of storms by his leech barometer. Which is to say, he was under a delusion. But in the way of much scientific inquiry in the nineteenth century, Merryweather’s credulous belief in the supernatural, sensory abilities of leeches would not be displaced – he thought he only needed to test his instrument further, to accrue more data, make larger mental leaps. To what extent was his own name – foreshadowing the doctor’s obsession with storms – to blame? How could a man called ‘Merryweather’ fail to shift the course of meteorological science?

When Merryweather received notification that the tempest prognosticator would indeed be exhibited in the Great Exhibition alongside objects including the world’s first hydraulic press, early cameras and daguerreotypes, a fire engine, a model for a floating church, hundreds of kaleidoscopic stuffed and mounted hummingbirds, and a multum in parvo knife comprising nearly two thousand lancets – did Merryweather then bounce on his tiptoes? Did he clench and unclench his dampening hands in anticipation? Picture it. You too might be able to see Merryweather’s lucrative future flashing in his mind, bright as a blade in the sun.

The tempest prognosticator has certain consistencies with objects we have encountered before, and which a few people remain inexorably fascinated by. Glass-cased tall clocks flicking in stately houses; the brass mechanisms of heirloom music boxes (that type you unlock with a trinket key); Steven Millhauser’s fictive miniatures of the orient; humanoid automatons set with weights, gears, pulleys. I think, specifically, of the Maillardet brothers’ ‘Juvenile Draughtsman’ of 1800, a harlequin-faced marionette – half-burnt to death in a house fire – that, by way of unwinding springs, draws over and over again fat and shaky cupids, and the stricken verse of a heart that’s charred, in two languages. The prognosticator is like these curios in the sense that it represents an attempt to house something as ineffable and infinite as time, art, writing, love or the weather within the gadgetry of a vendible and legible possession.

In the quivering of a leech Merryweather saw the electrical forethought of a deluge, a nest of lightning or the switch of total atmosphere into a blizzard. But when he tested his prototype across the four seasons of 1850, the doctor’s letters record that in spite of all his advocacy and conviction the leeches did not reliably predict the locality or the timing of storms. Perhaps the leeches recorded the colours of clouds not found in the evolution of a healing bruise, fragrances of weather unknown to us, or configurations of brightness in the atmosphere that human eyes cannot distinguish between. But it seemed they moved only capriciously in the tempest prognosticator, tinkling the bell according to leechy whim.

Instead of rejecting or modifying his hypothesis – or selecting a different ganon of leeches – Merryweather persisted. He chose to reinterpret his results and connect the engine of the hirudo medicinalis’ activity to storms that were days, even weeks, hence. He begun to assign to his leeches an almost omnipotent sensitivity not only to the wattage of storms happening in far-flung zones (then, as now, it is always raining somewhere in Europe), but to tumults of geological and astronomical phenomena. ‘I fully expected to hear of meteors’, Merryweather wrote when ‘a delightful serenity’ persisted in Whitby despite the leeches’ frenetic ascension up into the collars of their bottles. A comet over Edinburgh confirmed his proposition, that the sentience of the hirudo medicinalis stretched to astral turbulences and starry commotions beyond the weather. When craters widened in the side of Mount Vesuvius and earthquakes shuddered under Smyrna, Merryweather saw his leeches in surging circuitry with the violent, subterranean fermentation of metals, flurries of flammable and vapory streams from fissures, and all kinds of deep, tectonic weather.

In this way, Merryweather proves, I think, one of the first self-described scientists in Europe to imagine that the weather was a global system, even if his tempest prognosticator failed to warn of nearby storms. The tempest prognosticator prefigured a kind of thinking that seems self-evident from our age – that the meteorology of Earth is influenced by volcanoes, by surging electricity, by forces planetary in scale. During Merryweather’s time, this notion remained a fiction. There were no other means to test it.

Automaton

I don’t know why, but in writing this essay I have kept on thinking about an experiment I desperately wanted to stage as a child, but was never allowed to. I will write it down, to do as a leech does – purge it. Here’s the method of the experiment: you went out and bought a fresh piece of liver from the butchers, the fresher the better. You had to ask the butcher to wrap it in opaque paper not plastic. It was important that the liver hadn’t been exposed to too much light so ideally you would request one from the bottom of the heap in the butcher’s refrigerated display, though it didn’t matter what animal the liver was from – chicken, goose, calf, pig, whatever. You also bought a fresh pint of milk: again, the fresher the better. Probably raw milk would be best of all, though you wouldn’t have been able to get that back when I wanted to try out this experiment, at age nine in the early nineties, in the western suburbs of Perth. After nightfall, you removed the liver’s thin, outer membrane with a knife to expose its rawest matter, and you lay it on a saucer. Then you filled a second saucer with milk. You put both saucers under the bed, about a meter apart, and you went to sleep.

What was supposed to happen overnight was that the liver would crawl across the floor into the plate of milk. The milk would turn pink, and there would be a telltale trail of blood on the carpet. This had something to do with the enzymes in liver-meat, how they were attracted to molecules in fresh dairy products, (which was the reason the liver needed to be kept in the dark – light would cause the enzymes to photo-degrade). But I’m not sure now why the experiment needed to be conducted under a bed. Indeed, wouldn’t the presence of a human body above it in some way distract the liver? I only know that, as a child, the idea of the liver creeping like a red hand, under the bed, both terrified and electrified me. It does still.

Ectoplasm

Leeches are not as expensive today as they once were in the nineteenth century – a time when leeching was more than a cure-all therapy, it was a craze. You can (and people do) buy consignments of clinically farmed, sterilized (i.e. starved) hirudo medicinalis online. For a while, they were sold on Amazon. Medicinal leeches cost around $US100 for ten and, with the proper labels affixed, Australia Post will convey your leeches un-quarantined.

The sanguivorous appetite of the leech is claimed, in certain wellness forums, to ameliorate rheumatic conditions, infertility, hypertension, inflammation, chronic fatigue, and ‘four-hundred other diseases caused by insufficient micro-circulation’ (this from the British Association for Hirudotherapy’s website). I click on a link that begins: First Aid, or let us start with something really important, how to overcome fear of the medicinal leech. The leeches, sent from South Wales or Slovenia, or Auckland, are mailed in what appears to be, on the websites, ordinary cardboard boxes with cooling blocks inside. This amazes me. I cast a wary glance at a small ganglion I have developed on one ankle. Should I order some leeches? What results should I anticipate? A very important result of this is a sharp surge of joy and fun and also the cosmetic effect, which means that the leech is indeed a universal medicine.

The sharp surge of joy I do query.

But, alright, a few days ago a friend recommended to me a Korean brand of facemask that consists of snail mucous. Would it matter if I was typing this, sceptical of the therapeutic benefits of leeches but mostly convinced about the beauteous effects of snail slime, slathered liberally onto my forehead, cheeks and chin? What if I was looking at you through the screen of a faint skin of snail slime, right now?

The unsupervised, off-brand use of leeches in the home aside, leeches are still applied in surgical medicine too, though for more limited pathologies than they were in George Merryweather’s era. No scientist has yet been able to synthesize leech saliva, which has anticoagulant and vasodilatory effects and contains a subtle anesthetic (why leech bites aren’t painful). In reconstructive and plastic surgery, leeches are seldom – but sometimes – used to prevent clotting and abet circulation to little grafts. They’re becoming more common because the invention of micro-surgical lasers and finer scalpels has enabled doctors to reconnect ever smaller veins, in turn demanding more delicate implements for re-establishing blood-flow. A leech, to a surgeon, can be the gentlest knife.

I have decided not to order any leeches myself. I would say this is an ethical stance – I don’t want to be responsible for the leeches’ uncomfortable transit – but the truth is, I don’t know if I can come to see a leech as sanitary rather than monstrous, having jotted in my notes this morning a line from a book by Annie Dillard: ‘pieces of the leech’s body can also swim.’ Pieces of the leech’s body can also swim.

Séance

When a storm is rolling in, you can sometimes feel it, can’t you – even while the sky is clear? Like a body next to your body, unseen but sensed. Electricity, pressure, a grubby wind that pushes people back flat-palmed. The roots of your hair sizzle, the weather prickles beneath your skin. Lightning can split the daylight three times, into four pieces. X X X. This can happen (it has happened, it will again) though we can still see the moon, an afternoon moon mobbed of moonlight. Do you feel then, the way I do now, that:

The flash of the first lightning strike reveals the photographer crouched behind the curtain in that man’s bedroom. There is a photograph you’ve never seen of yourself. It is X-rated.

The flash of the second lightning strike shows the old lakes overrunning their brims. Water spills back into the car yards, the factories, it dowses the newspaper’s printing press. Men leave their guns behind and come splashing down from their towers.

The flash of the third lightning strike illuminates a rainforest clearing, never visited by humankind. Hundreds of moonstruck leeches writhe on the ground, coupling and consuming, becoming and undoing, oblivious to any weather watcher. In the mud are footprints, cloven-toed, though there are no tiny deer.

Drawing of the Tempest Prognosticator © The Wellcome Collection

Cover photograph © Doug Beckers