‘Seven-two-seven. You got mail!’ It took three or four years before Omar Deghayes heard those words. In that time he didn’t receive any post. Not even letters from his family. There were perhaps one or two, but after lawyers took up his case in 2005 he started to receive a lot more correspondence. In fact he started to get so many letters and cards that the guard who brought the post used to make a joke of it. ‘Oh, Omar,’ she would say with a smile, ‘you’re famous now.’

The first time I met Omar Deghayes while I was working on my book Guantánamo: If The Light Goes Out he was clearly still disorientated after nearly six years in Guantánamo.

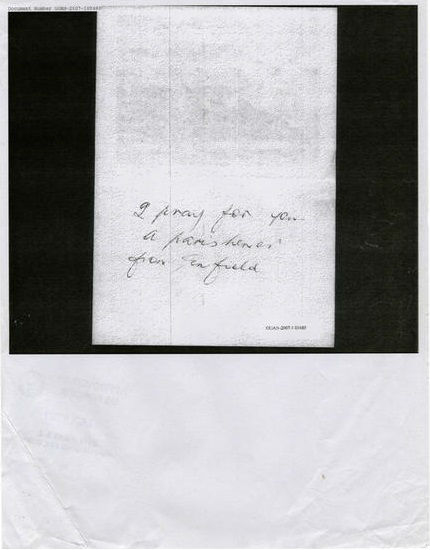

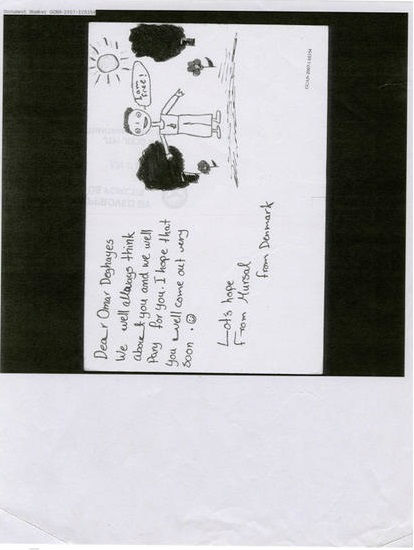

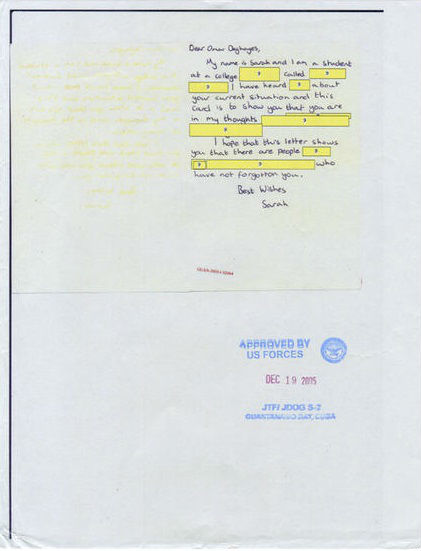

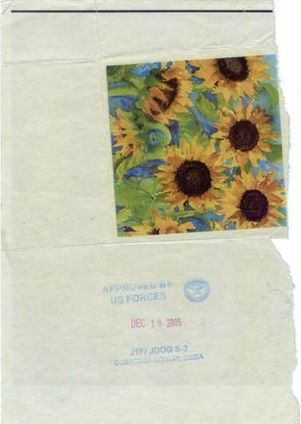

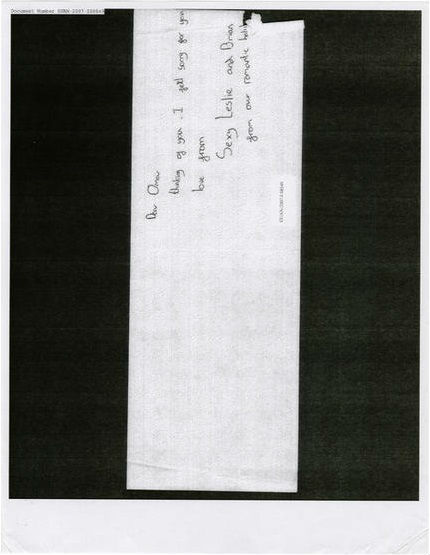

On one visit Omar spoke of sitting in his Camp 5 isolation cell, looking at some of the hundreds – possibly thousands – of letters and cards he received from people he had never met. A few were from his family and his lawyer, but the majority came from people around the world who wished to register their concern for his situation.

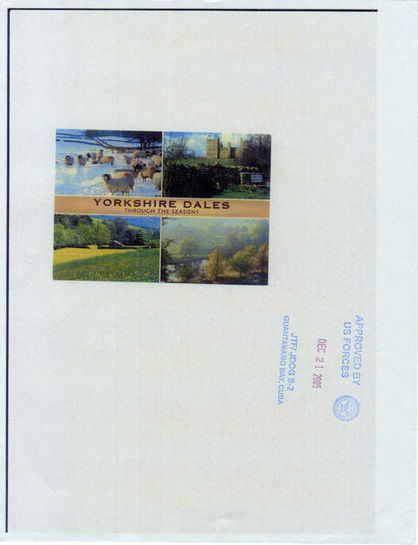

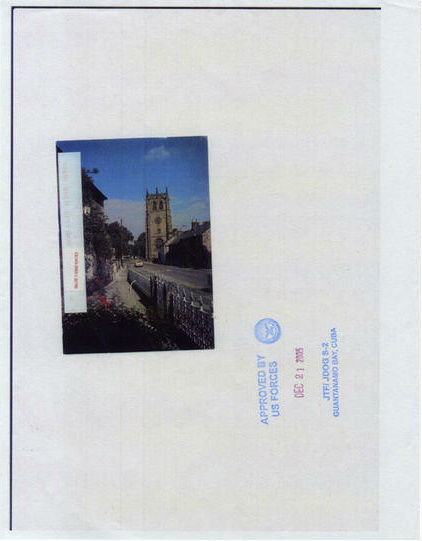

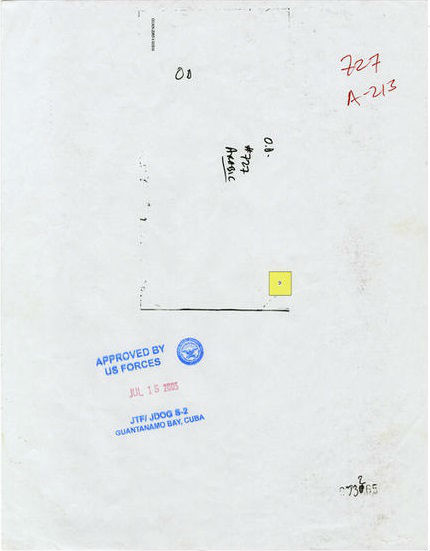

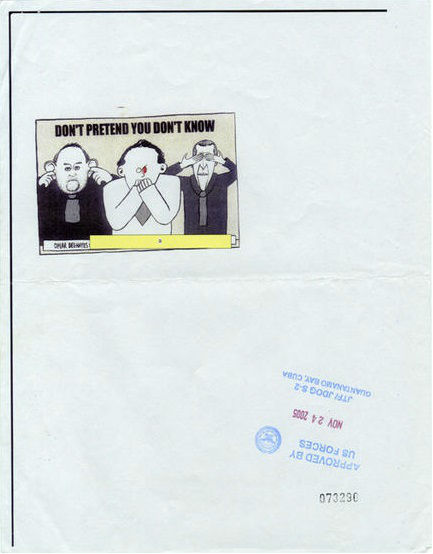

He was never given the original documents. Everything was screened for dangerous substances, redacted, copied or scanned – including the backs of envelopes and blank sheets of paper – officially stamped and given a unique reference number.

Omar refused to follow the rules of his captors and was designated a non-compliant prisoner. His mail became part of the control process his interrogators exercised over him. When and if he received anything, whether in colour or black-and-white copies, was controlled by his interrogators.

According to Omar: ‘It was all part of the system of rewards for good behaviour that could earn you another blanket, or trousers, or a cup. The guards did not let us have cups as they were afraid that we would throw something in their faces. Behaviour even determined whether we were allowed to have toilet paper in our cells or had to ask for it from the guards, sheet by sheet, when we needed it.’

These letters came to have a double-edged effect for him. He received so many that it afforded a degree of protection from his guards who realized how much attention there was about his case. Yet the scale and the strangeness of some of the material contributed to his paranoia to the point where he believed his interrogators were planting material to further disorientate him.

They reveal the scale of the American military’s control process and the choices, poignant and bizarre, that individuals made in terms of pictures and words to send to a man they had never met in a cell thousands of miles away. The combination of this process and these choices creates a series of visually extraordinary documents that testify to the dilemma of a man alone in a cell, thinking of home.

These eighteen letters are from a selection of over sixty included in the book Guantánamo: If The Light Goes Out, published by Dewi Lewis Publishing. As well as including the ‘Letter To Omar Series’, this award-winning book explores three notions of home through photographs from the prison camps, the US Naval Base that is home to American community at Guantánamo, and the homes of ex-detainees in the UK and the Middle East.

Omar Deghayes

Libyan-born Omar Deghayes spent his childhood holidays learning English near Brighton with his family. Persistent harassment and the death of his father, a prominent trade unionist, lawyer and critic of the ruling regime, at the hands of the Libyan authorities forced them to seek asylum in the UK. Omar studied law at Wolverhampton University where he became a practising Muslim. After university he travelled to Pakistan and Afghanistan to experience Islamic cultures. In Afghanistan he worked with NGOs and local businesses, married an Afghan woman and started planning his own law practice. After the US-led invasion in 2002, he fled to Lahore, Pakistan, with his wife and son. It was from here that he was captured by armed men in Pakistani police uniforms and handed over to the US authorities who were offering large rewards for Arabs who had spent time in Afghanistan. Deghayes was taken first to the Bagram military base in Afghanistan and then to Guantánamo where he was incarcerated for six years. The British government requested his release in August 2007 and he returned, released without charge, in December that year. Deghayes now lives in England and has remarried. He works with the Guantánamo Justice Centre and Reprieve.

Featured photograph by The Marion Doss