In collaboration with Dayannah, Gillianne, Kayla, Laurinda, Mimi, Nunjul, Rowrow, Tammara, Tricia and our families.

Though we have never met, Raphaela Rosella and I are tethered by carceral archives and a devotional love to family, friends and neighbors who have been swept away, disappeared or who are no longer alive due to the prison industrial complex. Both she and I reside in settler colonial states; she in Australia, I in the United States. For many years we have both worked within distinctly different, yet similarly marginalized, working-poor communities on the visual record of the carceral state and its impact on intimate life. Half a world apart from each other we have been amassing a range of personal images, letters and ephemera, alongside punitive mandates and carceral state records, which reflect both the violence of prison and the ways that criminalized and imprisoned people forge and maintain relations of love and care. As activists, artists and scholars of ‘carceral aesthetics’, we build new modes of belonging in collaboration with people impacted by prison, ways of imagining otherwise.

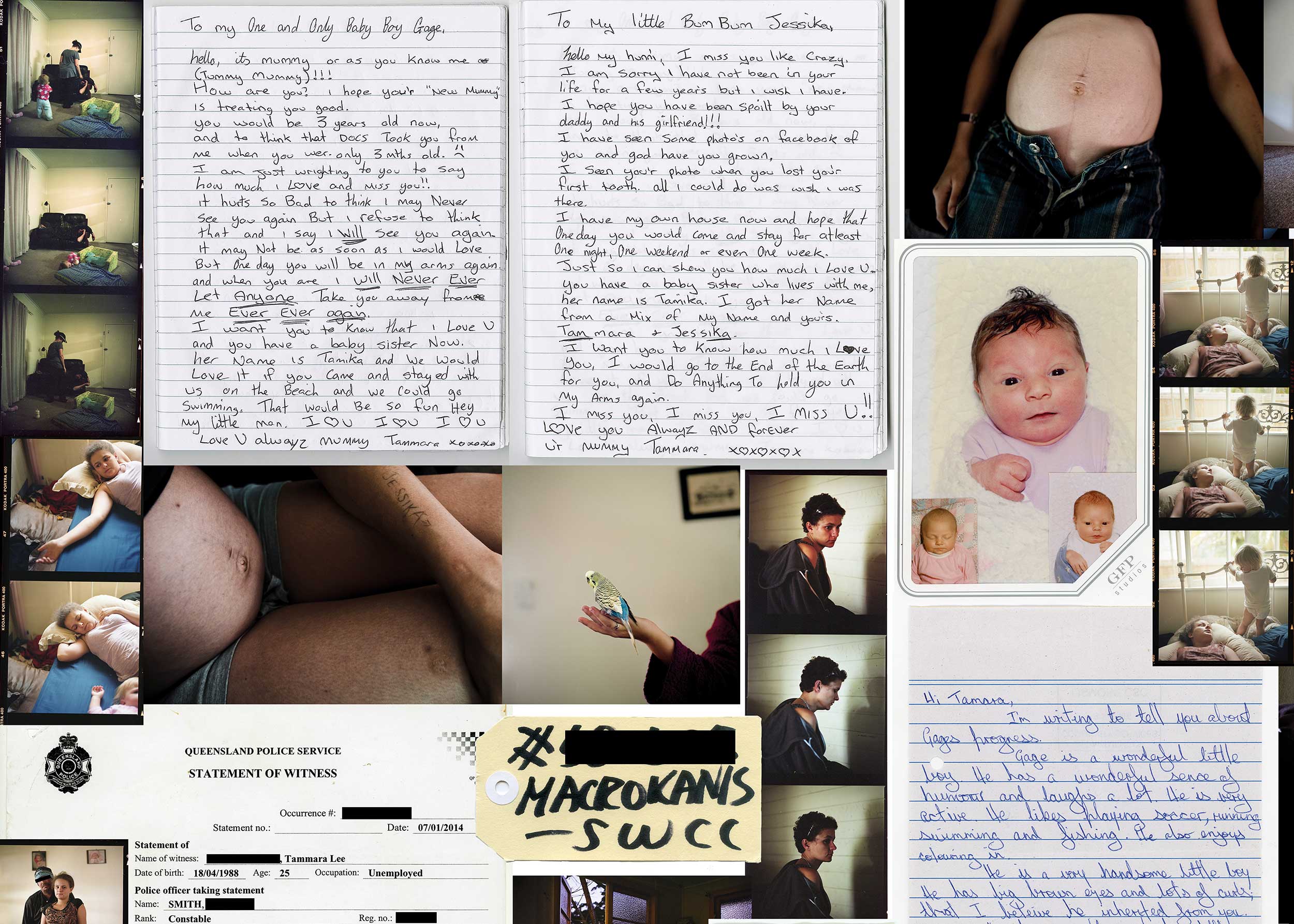

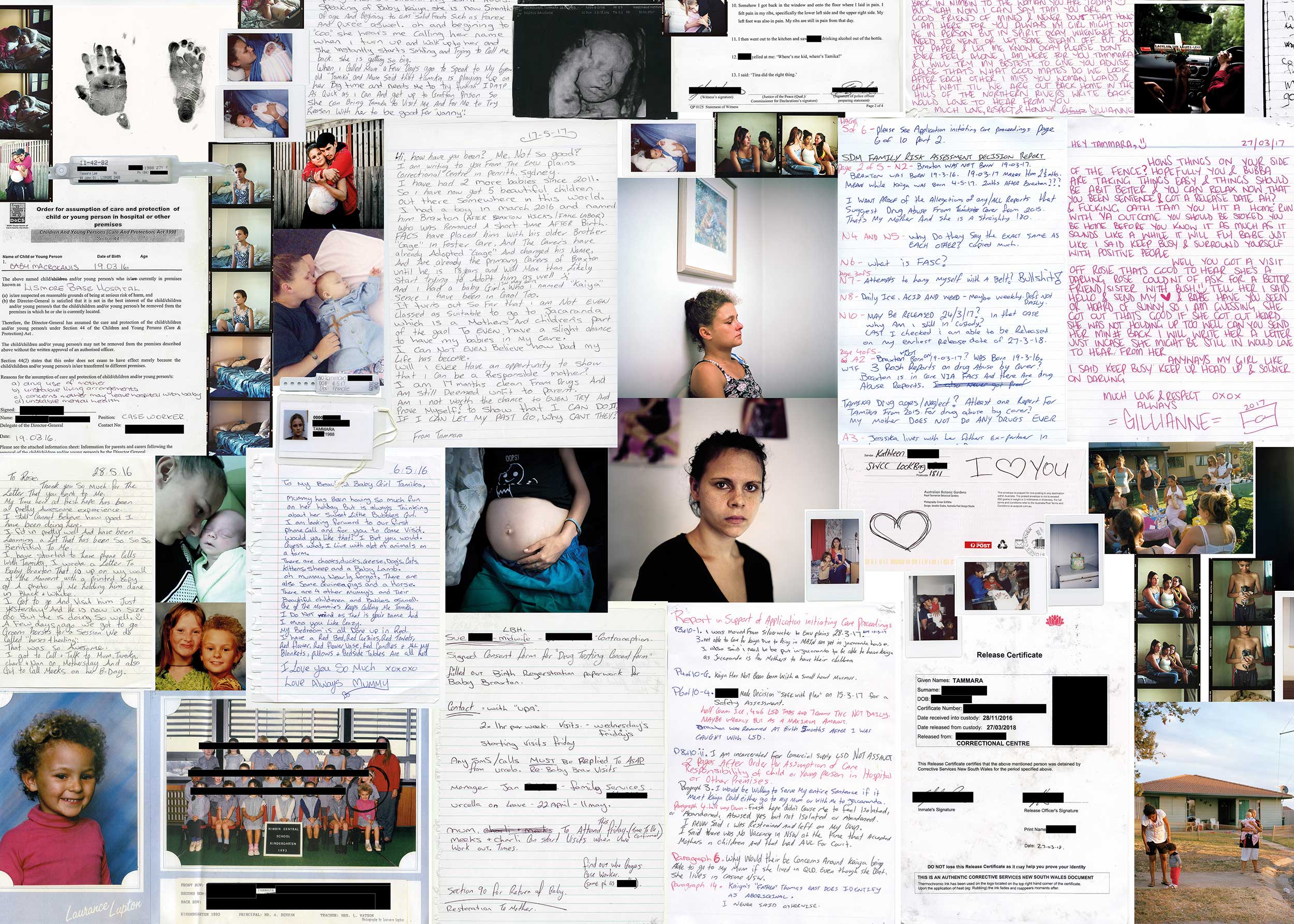

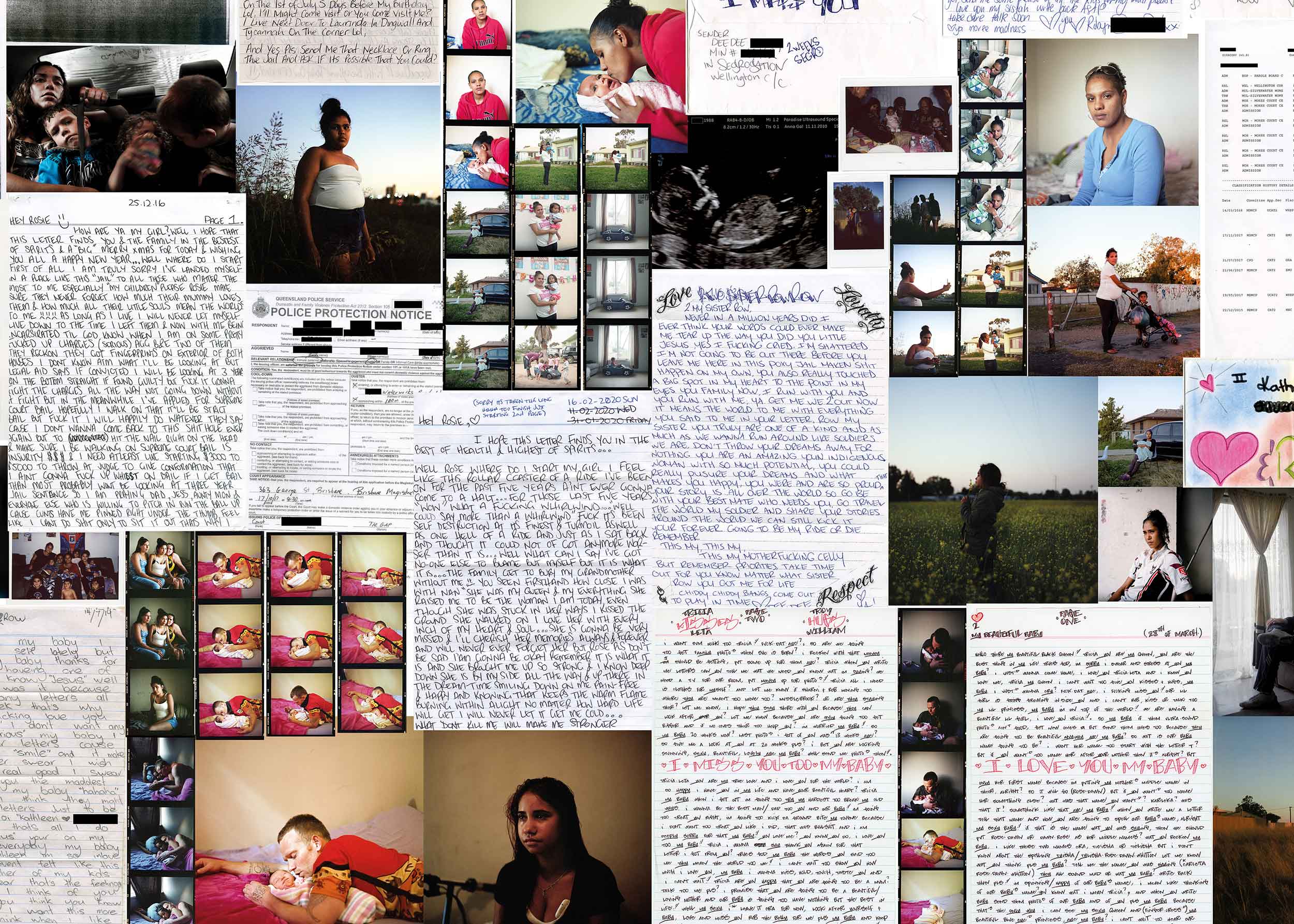

Rosella’s photo-based projects grapple visually with what American literary scholar Saidiya Hartman describes as ‘the power and authority of the archive and the limits it sets on what can be known, whose perspectives matter, and who is endowed with the gravity and authority of historical actor’. Focusing on criminal indexes and state records of arrest, custody and confinement, Rosella interweaves photographs of women in her intimate life – relatives, lifelong friends – with documents of state bureaucracies that criminalize them and leave them vulnerable to further punishment and marginalization.

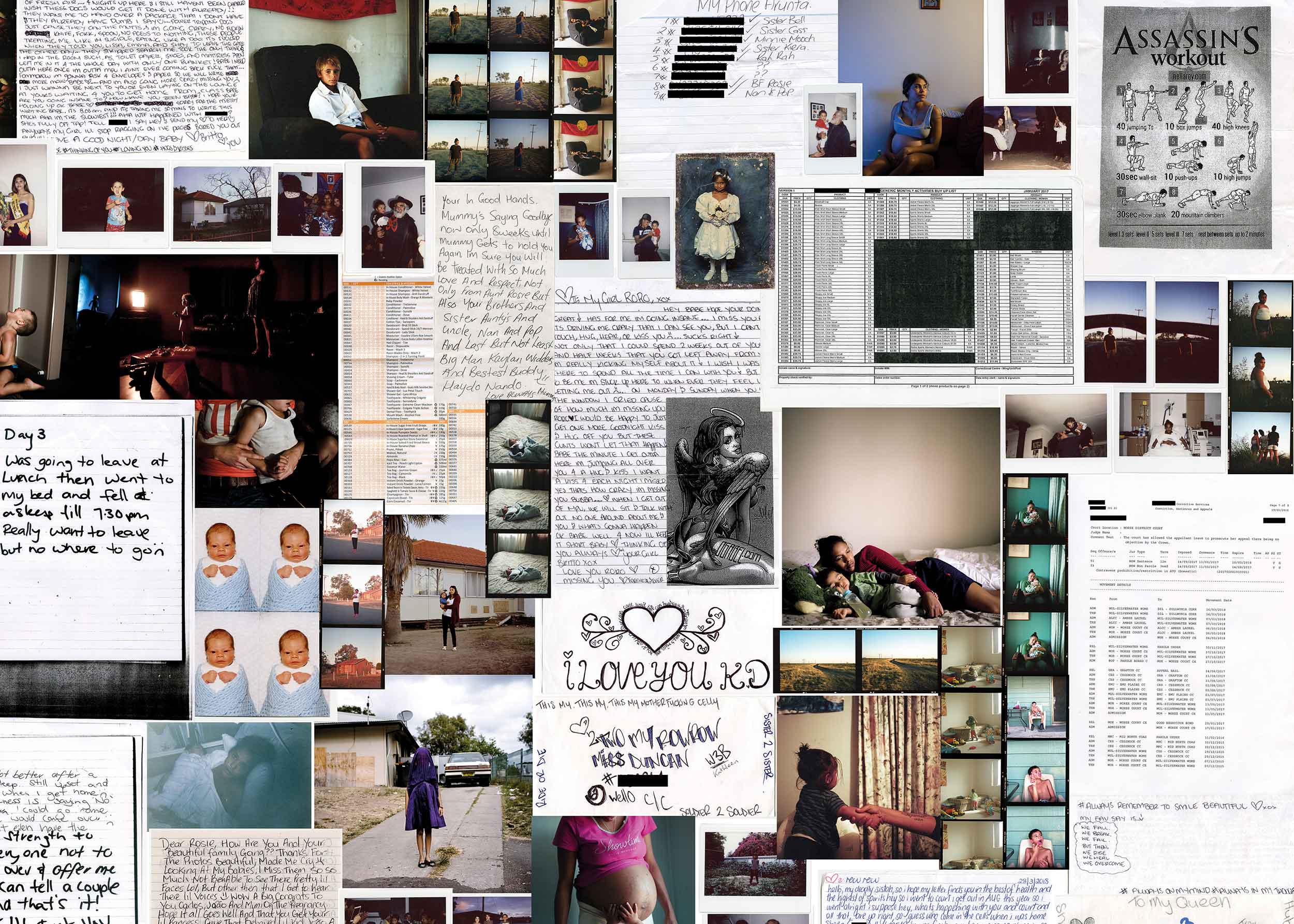

The images of women that appear in Rosella’s projects are not only photographs she located in state archives, but portraits of women in her life whom she has witnessed entangled by carceral bureaucracies, some never to recover or survive. The projects amount to counter-archives of state records, and are co-created by Rosella with Gillianne, Mimi, Nunjul, Rowrow, Tammara, Tricia and other women in her life who are subjects of these records.

Rosella, who is of Italian-immigrant descent, grew up in a lower-class family in a small town in Australia, where daily contact with the police was the norm. ‘It’s a heavily policed town, known for its alternative and open drug culture. The word “taxi” would echo throughout the main street each time the cops were spotted. It was a way we all looked out for each other in resistance to the relentless police presence that routinely harassed and surveilled our small community.’

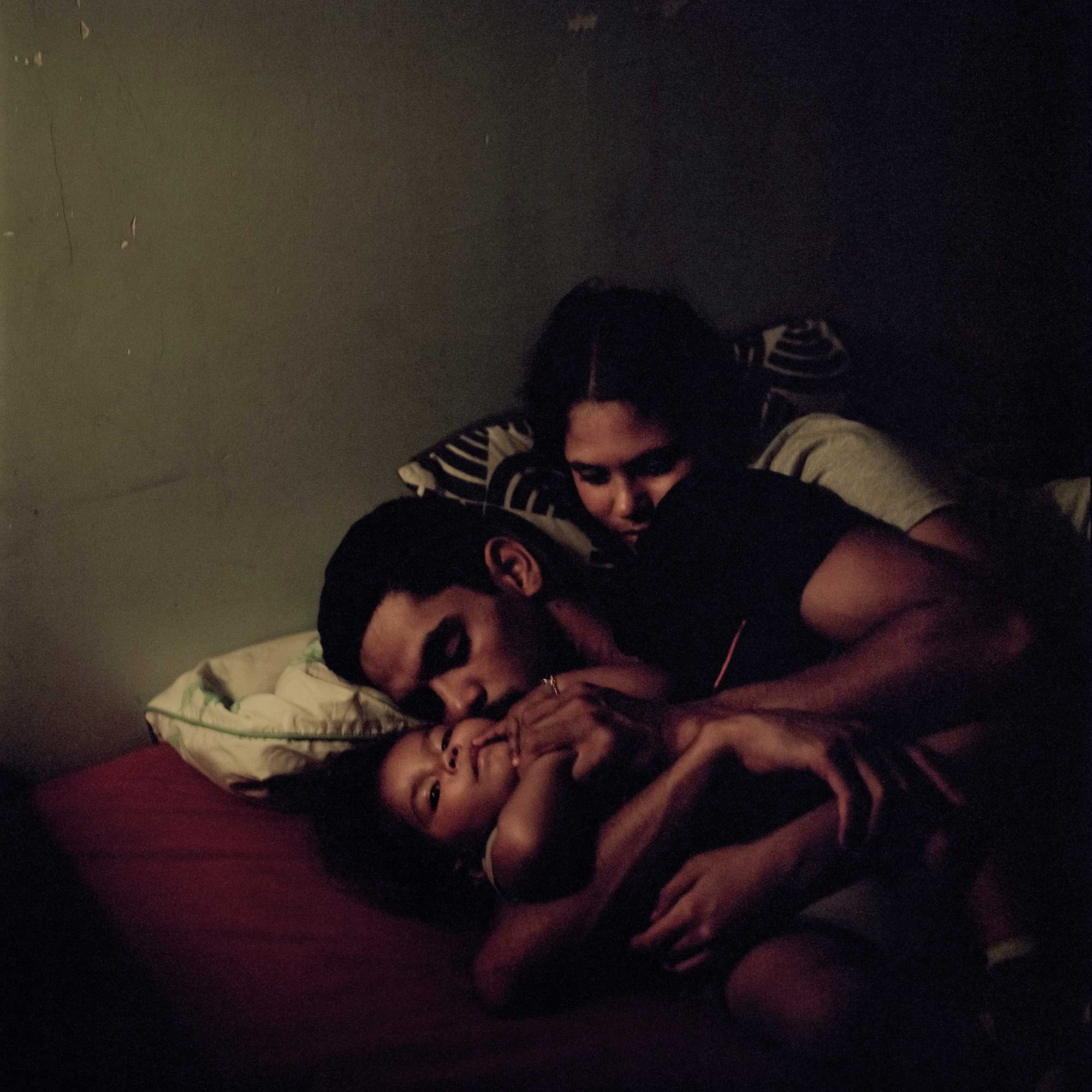

At an early age, Rosella knew that she wanted to be a photographer. While in primary school, she saved up for her first point-and-shoot camera. By high school, she was involved with a community arts organization documenting her own community, as well as other marginalized peoples and communities in Australia. She became the face of the organization, and was an internationally known artist by her early twenties. During this period, she photographed portraits and environmental images of communities in distress, like her award-winning portrait of a young girl, Laurinda.

Rosella is now ambivalent, even critical, of these early works, stating, ‘When you’re learning photography it’s instilled in you that you should try to win awards to elevate your career. The most sensationalised imagery and content were consistently winning these competitions. But that didn’t feel right. So I’ve pushed back against this in the kind of imagery that I make. Sometimes I just need to put the camera down and be present as a sister, family member or friend. And sometimes not every aspect of our lives is for an audience to see.’

After fifteen years of working in collaboration with this organization, strictly in the documentary tradition, Rosella grew increasingly concerned about the power dynamics of the archive, her practice and the organization that was facilitating and promoting the work.

‘I recently left the organization because I started questioning whether their projects were really moving beyond collaborative rhetoric. I started with them as a young, vulnerable teenager, and so did a number of my co-creators. We started as participants together. In recent years I noticed power dynamics were playing out in the work that I was making for the organisation. There was a big issue where one of my co-creators wanted to withdraw consent from one of their projects, and they just weren’t listening to her requests . . . This has led me to grapple with several questions within my personal practice; how can I work in a relational way without unconsciously forcing power over my co-creators, especially those positioned across varying states of unfreedom? I’ve now spent over fifteen years co-creating photo-based projects alongside several friends and family members from my childhood and adolescence. This has resulted in a co-created archive of photographic works, moving image, sound recordings, state-issued documents, love letters from jail and ephemera. So, who controls our co-created archive? These are the questions I’m looking at within my PhD.’

Co-creating with the women in her life, across several communities, evolved as a practice of refusing state narratives, resisting documentary objectification and counter-archiving the images and stories that mattered to them. ‘I have several co-creators, and some are heavily involved at times and sometimes they step back. But it’s definitely a relational process – I’ve been looking at relational ethics and those kinds of concepts. And I came across your work and “carceral aesthetics” just made sense, especially in terms of navigating carceral bureaucracies and surveillance.’

One of the first iterations of this co-created archive emerged as the series We met a little early, but I get to love you longer. Motherhood starts at a young age for the girls in Rosella’s community, including herself. In her early thirties, Rosella is a mother of three. Her twin sister became a mother at nineteen, and her step-sister had five children by the age of twenty-four. We met a little early, but I get to love you longer served as an opportunity for Rosella and the women in her life to self-document their experiences of mothering and care by combining existing state records and images with their own photographs and writings. Because young mothering is pathologized by the state as the source of a myriad of social ills, these personal archives claim this space as one of deep longing, loving and hope.