It was Bernard from the section who alerted me. ‘Hey, have you got a sec? I need to tell you something. You know the comrades were out near the depot yesterday? We were sticking up posters for the first of May when we saw that gang from the FN at the end of the tracks. They were sticking up posters for their Joan of Arc thing, under the bridge and all along the wall that goes up to the switch. We snapped in, there weren’t many of us, same as them, no better, no less tooled up than them. Nobody really wanted a scrap. Mimile and Ominetti had gone home already, and the rest of us weren’t exactly tough guys. And since they didn’t look all that much more committed than we were, we decided to shout a few insults and leave it at that. We spent another couple of hours slapping up our posters over theirs, and I imagine they’ve fucked with our work since then. That’s life, what do you expect?’ I didn’t understand what he was getting at. It was a long time since I’d been out putting up posters, and that kind of thing went over my head these days. It was a game, to see who got the last word. Everybody had their own territory, places where only their colours were acceptable. You should have seen them, some mornings, when they’d invaded the other side’s territory with their posters. ‘What bothered me,’ Bernard went on, ‘is that I think I saw Fus hanging with them. I wouldn’t stake my life on it, but there was this big bloke who had the look of your son. The guys didn’t notice, but I’m almost sure. A jacket with a big Apache on the back, is that him?’ ‘Maybe, well, no, I don’t think so,’ was all I could stammer. Bernard went on: ‘Don’t beat yourself up, young people do stupid things. Just don’t want him getting into trouble. You know how it is round here, there are some hard men who wouldn’t think before whacking anyone, even your son.’ And thumping me on the arm: ‘Shame they’re turning the kids’ heads like that,’ he finished. Fus was twenty-five, he wasn’t a kid. What was he doing hanging out with fascists?

When I asked him in the evening he said he didn’t know anything. He’d just gone along with his pals, it was the first time they’d gone out sticking up posters, and he wanted to see what it was like. While I thought that evening through, wondering what I was going to do, slap him, have a fight with him, in the end nothing happened. Nothing at all. Nothing I could have imagined. I didn’t have it in me to sort him out. That evening I felt incredibly cowardly, and very old as well. I remember looking out at the garden for a long time. It was really beautiful, the fruit trees were beaded with the thaw that had just begun, and an inky cloud said it was due to bucket down in half an hour or so. I should have gone back in and joined him, I’d prepared myself for a discussion, not even a bollocking. ‘How could you have done it?’ I asked him. He just said, ‘It’s not what you think.’ What could I have thought? And then he went on: ‘When did you stop putting up posters? When did you start just going for cake up at the section?’ I’d asked him if he didn’t feel awkward spending his time with racists. ‘They’re not racists, that’s the old days. Anyway, my mates aren’t racist, any more than you and I are.’ ‘No, not racist, just against immigrants,’ I added. ‘Against immigration, Dad, not against immigrants. The ones already here don’t bother them as long as they don’t mess things up.’ Normal people, in short. And then, as if determined to convince me, he said again: ‘They’re good guys. Not like you think.’ He had sat down at the end of the table. Perhaps he was waiting for me to join him, to go and grab a couple of cans that we could both neck down. I stayed in my corner, near the window, behind him. Keeping an eye out to see if Gillou was on his way back. Worried that he would find us like that. Fus went on talking softly: ‘Believe me, these guys are on the side of the workers, you’d have been together twenty years ago. They don’t care what people say in Paris. They’re only interested in this part of the world, they don’t want to see it die. They’re moving. They’ve had it to there with all the European crap. They get their cash from Paris and they redistribute it round here. Last Saturday, for example, after a poor old man got burgled, they fitted out his house from top to bottom. Like it or not, these guys aren’t exactly spitting on people.’ That’s how you justified hanging out with the far right in less than ten minutes. How you resigned yourself to your son being on the other side. Not the side of Macron, but of the very worst bastards. The mates of holocaust deniers, absolute scum. Fus was calm, almost contented, that this explanation had hit home. He assumed. A real Jehovah’s Witness, head stuffed with nonsense, new certainties, and still lovable. I was ashamed. We were going to have to live with it from now on, that was the most awkward thing. Whatever we did, whatever we might have wanted, it was done: my son had knocked about with fascists. And from what I could tell, he’d enjoyed it. We were in one hell of a mess. La moman could be proud of me. In the end Fus got up and said, ‘It doesn’t change anything.’

—

In all the weeks that followed, I didn’t go out except to work. I avoided bumping into him, but it wasn’t always possible, and then there was Gillou. We behaved ourselves over meals. We avoided starting debates. It was Gillou who did it in our place. We still agreed on plenty of things. Wondering how it’s possible. How could he love what we had always loved, when he was hanging out with fascists? He kept on humming la moman’s favourite Jean Ferrat songs,2 as he had done since her death. Christ’s sake, did he understand the words? ‘Desnos leaving Compiègne to fulfil his own prophecy.’ How could he go on singing that song? Now he was hanging about with the same people who’d bunged the poet on the train. And yet I didn’t say a word. Just once I asked him to be quiet, Gillou looked at me and smiled at his brother, a wink, ‘the old boy isn’t in a great mood tonight’. Luckily Gillou didn’t understand. All the better.

My thoughts kept turning back to it. And yet, as he had said, it didn’t change anything. I went to see him at the stadium. When he went out with his gang, he did it discreetly, as if he wanted to avoid hurting me any more. He had a certain regard for his stupid old dad. There were even long weeks when he stayed at home to revise for his end-of-year exams. I’d hoped for a while that it was over, that one evening he’d say, ‘I don’t know what I was thinking,’ and come back to me. A moment of pure relief. Going up to the section together. To visit the grave of great-uncle Laurent, CGT member from the very beginning and deported, buried under red and tricolour flags. But that’s not what happened. Quite the reverse, he started going out again.

One time a guy from the gang rang the bell. I opened the door to him. Nice face. Normally dressed. Very polite. I brought him in, we exchanged a few words, because it would have been hard to do otherwise. I even think we shook hands. Mechanically. He complimented me on the garden, said it was his parents’ hobby, and that he sometimes gave them a hand. What could I do? Now that I’d let him in, now that we’d talked a bit, I wasn’t going to have a row with him. I wasn’t going to run away either. Fus had taken some time to leave his room. I looked at him again. A healthy, athletic fellow. Open expression, lots of character. Not nasty-looking at all. The type of guy you’d wish your kids would have as a friend. At last Fus showed up. They both spent ages saying goodbye to me, two good mates. They left arm in arm. They got into a little chrome van, probably hired.

Throughout the day I’d thought of that guy time and again. I’d tried to imagine him chasing after Arabs at night and beating them up. But it didn’t work. Not for my son either. But they must have done things together. Fascist things. Otherwise what was the point? However much I struggled, none of it stuck. It all slipped away from his angelic face.

When Fus came back that night, contrary to his usual habits, he didn’t go up to his bedroom, he came and joined me in the kitchen. ‘That was Hugo,’ he said, ‘His parents live in one of the houses near the Beller stream.’ As if that was supposed to put my mind at rest. Little workers’ houses, most of them done up, not far from the railway station. I didn’t know anyone there since Armand sold his to a couple of young nurses. ‘They’re nice, you should see their garden . . .’ ‘I know, your pal told me,’ I interrupted. Fus just said, ‘Ah, fine, good.’ I set about furiously grating carrots, which kept my head down in the salad bowl. Between the desire to go on talking, to find out more about this fellow Hugo, about what they’d done that afternoon and not dropping the face I’d been putting on for him for several weeks. He stood beside me for a long time in silence, stiff as a plank. He was waiting for me to open up, which I didn’t that evening. Then he started emptying the dishwasher, complaining that it had stopped washing anything properly, which wasn’t completely untrue, but I’d been avoiding that expense for months, and after hand-washing what needed to be washed, conscientiously wiping away any lingering scraps and putting everything away nice and clean, he finally had a good reason to cut short our session and leave the kitchen. For my part, I had the feeling I’d already done a lot, and I was pleased that we could live together without hitting each other.

He and his guy Hugo and some others collected old furniture locally, wardrobes, heavy black antique cupboards which they refurbished to sell on. After stripping them down and giving them a good wax, they made them bearable. Or else they painted them in the colours that people like these days, taupe, bright green. Most of them went like hot cakes, and the stinkers that found no takers went straight to the poor. I knew all that from Gillou, who followed his brother’s exploits from a distance. They seemed to have a good laugh on Facebook. You saw them stripped to the waist working away at their planks. The studio was a total tip, beer bottles all over the place, tags on the wall that were hard to read. Some of them had cigarettes in their mouths. With long hair and pony-tails, they wouldn’t have been out of place at one of our youth clubs in the old days. Now it was more of a short-back-and-sides look. There were two or three girls in the pictures, and they looked almost scary. They didn’t seem to do much in the workshop, just watched the guys doing their stuff, sitting on a work bench, big Doc Martens on their feet, army trousers, men’s tank tops. Their faces were filled with arrogance and hatred. And if only it had stopped there! The page went on to say things about rap music that I didn’t get, but then there were a bunch of comments in which they fucked and bollocked anything that wasn’t certified as pure white. Jews and queers got the worst treatment, followed closely by Arabs, but like all the rest it was accompanied by a long sequence of little smileys, so I shouldn’t imagine any of it led to anything of any consequence. Every now and again, some messages asked them to rein it in a bit, moderators or little local bosses who didn’t want Paris whacking them over the knuckles, but the whole thing was revolting. So Gillou was aware of what his bro was up to, and I’d been naive to imagine that I was protecting him from all this. ‘So you know?’ I asked him. ‘Yeah, but it doesn’t change anything,’ he answered simply. He was another one, then. I was the only one who found anything to object to. ‘Nothing about this shit shocks you, it doesn’t bother you that your brother’s involved in it all? Does that mean you think the same as him?’ ‘Dad, Fus isn’t like that. His mates are a bit wacko, but he’s still sound. And since they’ve been doing their restoration work I don’t think it’s been all that bad. No one forces them to do it, and it takes up their Saturdays. They’re better off doing that than hanging around in the local bars.’ ‘But don’t you feel like telling him he’s messing up?’ I pressed. Gillou just said, as he often did, ‘Chill.’ I don’t know what faith he was relying on, how he imagined the return of the prodigal son. ‘Chill.’

We moved on to the next stage and it stayed like that for several weeks. Apart from his studio, and when the weather permitted, Fus camped with his mates about ten kilometres away from us in quite a nice neck of the woods. A farmer had – under what sort of pressure I don’t know – let them have a tiny plot with a cabin on it that they used as an HQ. They’d put up tents all around it, reinforced with planks and canvas. I regularly consulted their Facebook page, without Gillou’s help. And I saw the same faces. Their thing looked like a squat. As in all squats, nice things grew surrounded by shit. They’d built a beautiful veranda where they had their drinks. Gillou had said to me, ‘You see, they don’t care about politics, what interests them is doing that kind of thing, hanging out.’ And it’s true that just looking at those photographs, and if you bleeped out all the rest, if you didn’t read the disgusting comments that their page was stuffed with, you could have imagined that everything was fine.

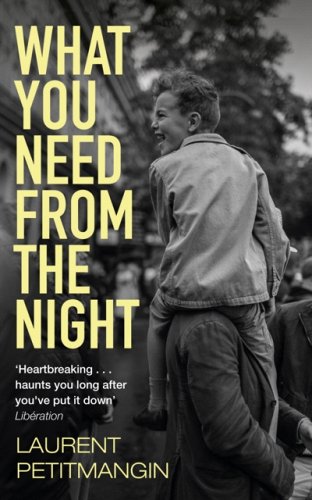

Photograph © Bladsurb

This is an extract from What You Need From the Night by Laurent Petitmangin, published by Picador in the UK and Other Press in the US.