The summer storms that rumbled through the valley were particularly intense at night. We would watch the raindrops drive into the darkness from the long rectangular window in my parents’ bedroom which, located at the front of the house, gave us a view of the line of trees separating our cottage from the one in front. The branches of the trees, two towering lindens and an elm, thrashed wildly as their trunks swayed perilously back, forth, sideways.

Gripping the windowsill as if she were clinging for purchase on a rolling ship, my great-aunt Palička would, without fail, make the dire prediction that we would surely all die in our beds that night.

‘It’s likely’, my grandmother Sasha would respond, her hands in my sister’s hair, stroking her head reassuringly. ‘I know a little boy who was crushed by a tree only last year’.

Their warnings did not lose their power through yearly repetition but rather accumulated it, growing more frightening with each reiteration. I would tuck myself into bed in my wood-panelled room and wait for the walls to splinter.

In 2004, my family and I travelled from the UK to the Czech Republic for our annual summer holiday. We clambered out of the car, empty soft drink bottles cascading onto the ground, to find a scene of devastation. The linden had fallen in a storm. It had sliced through the cottage directly below ours, cracking the roof in half and sending wooden tiles pouring down. Its boughs were stuck through the upper floor where the bedrooms were. Somehow the chimney stood, but off-kilter. The linden is the Czech national symbol, traditionally planted outside houses because, in Slavic folklore, it was believed to protect against evil spirits, lightning and hailstones. Of course, this means that should you happen to get crushed in your bed one night, it’s likely to be by a linden.

No one was killed on this occasion. I knew this house was where a ‘very old German lady’ had lived – my parents had whispered this information to me – but she had left a year earlier, when she could no longer live alone. Her cottage had been empty since. When she had lived there, I had not understood the prying, curious glances my parents would direct at her lace-curtain-covered windows, or the awkward gravity that slowed their bodies when walking up the meadow path that crossed behind her house. I wasn’t sure what I was meant to make of the information, always delivered with a knowing air, that she was: a) ‘very old’, b) ‘German’, c) ‘a lady’. Or, which of these categories was the cause of my parents’ twitchiness. Nor why Sasha and Palička, my guides to the neighbourhood, never acknowledged her presence at all.

The constituent parts of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy tale were all there. Undulating hills with deep, dark woods. A cluster of cottages, painted in brown, black and white stripes, plumes of woodsmoke above their roofs. A sinister older woman I never once caught sight of. But, like any childhood fairy tale, once you take a closer look, listen more attentively, you find that lurking underneath the familiar is a horror story. My Czech family’s house stands on a geopolitical rift: it occupies a place the political storms sweep through, uprooting everything that is settled. Only when I became an adult and began to investigate my family’s history did I realise – the connection emerging slowly – that the ‘very old German lady’ had been the last survivor of a German community that was forcibly displaced from the region by Czechs over fifty years ago. No wonder my family were so jumpy around her house. She was a living spectre, a ghost that pottered about in her living room, screened from the world by white lace. Her quiet presence on the mountain posed questions as urgent and insistent as an itch. How are you supposed to live in a place that has been ethnically cleansed? What do you accommodate from that history and what do you repress, ignore, avoid? There is no guide for making a home on resettled land.

–

My Czech family’s cottage, 823 Marian Mountain, is situated in the Jizera Mountains, the low-lying foothills of the Giant Mountains, which form the frontier between the Czech Republic and Poland. Surviving pockets of primaeval beech forest – where the bark of the slender trees is as silver as shark skin – are littered with moss-covered granite boulders, arresting in their size and incongruity, left behind by glacial advance and retreat during the Last Ice Age, 115,000 to 11,700 years ago.

In the sixteenth century, German-speaking colonists moved over the border and established glass works, coal mines and textile factories in the mountains, cutting pathways through the dense woodlands and replacing the beeches with fast-growing spruce, better for fuelling blazing industrial furnaces.

A house was built on the cottage’s site sometime before 1843, but the local property records for the house begin with a man named Josef Prediger and his wife Anna, born in 1873 and 1876. Josef worked as a supplier of glass beads that were used to make glittering costume jewellery and chandeliers that hung in grand rooms across Europe and America. They lived in the creaking Austro-Hungarian Empire, a sprawling, polyglot state whose German national anthem had to have versions in Czech, Croatian, Slovene, Romanian, Italian, Ukrainian and in assorted dialects.

As Josef and Anna scratched out a living, nationalism was gradually eating away at the Empire like acid. In 1918, following the First World War and Austro-Hungary’s resulting collapse, the Czechs were given a nation under the direction of the Allied victors. On 18 October, the day that the Czechoslovak independence agreement was signed in Paris, Josef and Anna suddenly found that a border had been imposed over a place where, for many generations, nationality had been soft, blurred. And, worse still, they were on the wrong side of that border. They were not alone: Czechoslovakia’s perimeters to the north, south and west were now home to over three million Germans, who altogether made up 23 per cent of Czechoslovakia’s population. The German community gave the topographical fringe on which they lived a name – the Sudetenland.

In 1934, Josef died and a different Josef, a cobbler with the Czech second name of Machatý, moved in with Anna and her two daughters, Anna and Elsa. At this time, support for Hitler, Germany’s new Chancellor, was growing steadily among the Sudetens. One year before the new Josef moved in, the Sudeten Party was formed. Its aim was to break from Czechoslovakia and join Hitler’s Third Reich, returning Sudeten Germans to what they understood as their national territory. By 1938, it had become one of the largest fascist parties in Europe with over a million members.

Nazi Germany, searching for Lebensraum, capitalised on rising nationalism by seizing the Sudetenland in September 1938. The force of the German claim on the territory was sufficient for the Allies to legitimise the landgrab at the Munich Conference. Encouraged by their tractability, Hitler’s forces occupied the rest of Czechoslovakia the following year, an act that propelled Europe towards the Second World War. Local men left to fight for Germany on the Eastern Front, forcibly drafted to the frozen battlefields of Stalingrad and Leningrad. Perhaps Josef was shipped to the East on the trains that moved millions of German troops into Russia. The property record does not list his death date, but the cottage became vacant in 1942. Ervin Endler, a glass cutter, moved in with his wife Marie and daughter Ilse.

In a local chronicle in which the property records of all the houses on the mountain are collated, there is a black-and-white photograph of the three of them standing outside the front wall of the cottage beside a bush covered in white doily-like flowers. Ervin’s face is obscured by a flat cap and thick, dark moustache. Mother and daughter are wearing aprons over their pale shirts. Ilse has her strings tied in front, dangling from her waist; Marie’s are invisible, tucked neatly away in a workmanly fashion. The back of Marie’s head, her hair cut short, is reflected in the windowpane behind her.

Four years later, following the end of the war, the Czech government ratified a set of decrees that expelled all Germans from the Sudetenland. Demobilised soldiers, security forces, and neighbourhood militias enforced their implementation, entering homes and evicting their inhabitants, sometimes forcing the Germans from their beds in the early hours of the morning. Newly-liberated concentration camps were brought back into service, providing the temporary holding spaces needed to move people on a large scale.

The figures are debated, but by 1946, roughly 1.3 million Germans had been deported to West Germany and 80,000 to East Germany. They were permitted to take only 30 to 70 kilograms of luggage per person and their abandoned homes were taken into Czech national ownership. Only glass experts – grinders and cutters like Ervin – were permitted to stay, a privilege they were granted because their industrial skills were considered vital to the Czech economy’s post-war recovery. The parents of the ‘very old German lady’, who would have been then a very young girl, were in the same profession. From 1946, empty German cottages began to be sold off to Czechs as holiday homes: my family bought theirs from Ervin, who retired from glassmaking and moved to the nearest village, in 1955.

Now only Czechs live or, more often, holiday there. It is a strange place: at once a bucolic idyll, where the sunlight comes down in sheets on the meadows, and an industrial graveyard, where the skeletons of production lie. Its landscape – a dense collage of dark and darker green spruce – was created by a community that no longer lives there, to serve an economic need that is no longer. The mass departure of people, carrying with them their knowledge and skills acquired over centuries, arrested manufacturing in the region. Abandoned nineteenth-century factories, their windows broken and paintwork worn out to pastel, lie among the trees, their smokestacks home to stork nests. It can feel like a place of transit where nothing is rooted. For that reason, it is best not to form attachments to local businesses. New pubs and restaurants open every year and disappear, gone bust, by the next.

Perhaps this quiet decline is an inevitable result of a national amnesia which prevents Czechs from recognising the scars left by displacement. The Czech government – like any other state – has a myopic view of its own history. It’s not surprising that their vision blurs when it comes to focusing on an ethnic cleansing that took place in Europe’s heart, albeit one perpetuated by the rightful victors of a just war. In Germany and the Czech Republic, there are a handful of organisations that continue to argue for the rights of expelled Sudeten Germans. Some demand a formal national apology, a few even the restitution of seized property. Neither are forthcoming.

At the cottage, this history rarely came up in conversation, aside from the occasional veiled mention of the ‘very old German lady’. It’s funny, the avoidance of the uncomfortable, because both Sasha and Palička – who are identical twins – are fixated with death and the morbid. They love to inject horror into the everyday, bouncing their fears off each other like a pair of mirrors that reflect and distort. Sasha seemed to know hundreds of little boys and girls, all of whom had died doing whatever it was that I happened to be doing in that moment – standing on a chair, jumping over the sandpit, squirting whipped cream directly into my mouth from the can. It was like she was haunted by a chorus of children urging her to protect me against domestic accidents. The two of them would unwind in the evenings by watching a television show about fatal car crashes – complete with faithful reconstructions featuring beige crash dummies – sitting side-by-side on a pair of deer-skin armchairs, absorbing new stories with which to frighten us. Keeping the focus small, on tragedies that might occur to their immediate family, in their home, was perhaps easier than pulling back and looking around at where they were. For their generation, who were only children when the Sudetenland changed hands, it was still conceivable that the Germans could come back anytime and reclaim their house and land; a revenant could knock on the front door.

–

Although we didn’t talk about it, inside the house, we were all bumping up against the past anyway. The cottage is like a local museum. Walls, shelves, cabinets – every available space and surface – is full of antiques and memorabilia. The hall, where a dark timber staircase descends to blue-and-white speckled tiles, is hung with agricultural tools – most of which I couldn’t name or even begin to guess the purpose of.

Saws, axes, a wooden hayfork, pliers, wooden combs with broken teeth, and a cracked leather harness for a carthorse.

Maps in assorted frames, some cheap, some sturdy, record former topographies, attesting to the political layer cake that makes up the Czech Republic, or now, Czechia. One map of the local area, pale-green, small, and square, shows ‘Albrechtsdorf-u-Marienberg’, the German name for what is now Albrechtice. A postcard of Isergebirge Spitzberg, which I know in Czech as ‘Špičák’, shows multiple shots of an observation tower, edged with curling Arabesque borders.

Also distributed around the whitewashed walls are a series of black-and-white photographs.

A cottage – captioned in German as ‘Marienberger Bauden’ – sunk into deep snow with the inhabitants gathered outside swaddled in furs. Some are sitting on wooden sleds. A line of slightly darker snow up to the front door indicates a path trodden into the frozen drifts.

A farmer’s wedding (titled, in white hand-written letters, ‘Bauernhochzeit’) on 7 November 1920. At least four horse-drawn carriages are lined up on a track. Everyone in them is wearing hats. The trees are bare of leaves.

Twenty-two little boys lined up in 1923 to celebrate the fifty-year anniversary of Hungary’s incorporation into the Austrian Monarchy. They are wearing Pickelhaube helmets and belted white military jackets. Three of the boys are standing on a ladder. A rope runs through their hands. One of the boys lies on a stretcher – either he’s ill, or their mock army includes a mock field hospital with mock patients. It is only after you have looked at the picture for a little while that you notice three more boys, standing on the top rungs of three ladders, behind the rest of the group.

I realise suddenly that I have spent my life holidaying while being looked over by the faces of the people who were expelled, and the faces of their parents, and grandparents.

It was so easy to miss them; they were tacitly accepted as part of the furniture. In the kitchen and bathroom, postcard-size prints of 1930s German adverts decorate the walls. At first glance, they’re the kind of prints that you might see almost anywhere, like the Chat Noir poster that hangs in every cafe and bar – art so loosed from its place and origin that you neither register it nor pay attention to what it shows.

An advert for a Miele laundry machine, a great big wooden drum like a barrel, resting on wooden pallets with a metal crank. A woman in a long white apron leans against it, one pointy black leather shoe crossed in front of the other. The German text asks her: ‘Are you still afraid of the big wash?’ She replies: ‘Not anymore. I have a Miele!’

An advert for Pfunds Milk Soap, made in Dresden from ‘the best pure cow’s milk’. Two blonde children, flushed and pink, are in a sloping tin bath, helped by their mother, dressed in a cerise blouse with puffed sleeves and a black trim. One boy faces the viewer, holding a white enamel bowl in which a white bar of soap rests.

Happy wives with cherubic children making happy homes, where everything is spick and span, and there is no dirt on either clothes or bodies. All perfectly innocuous.

A word comes to mind: kitsch. Kitsch is a form of art that excludes the unacceptable, that prefers the saccharine to the ugliness of the real world. It is associated with totalitarianism, especially with the regimes that occupied the Czech lands: the Nazis and then the Soviets. In the Czech writer Milan Kundera’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being, Sabina, a painter who secretly experiments with abstract art under her communist-approved canvases, reflects that kitsch is used to screen individualism, doubt and irony. It excludes the unpleasant. It is ‘the absolute denial of shit’. This makes the gulag – or, perhaps, a holding camp of expelled Sudetens – society’s ‘septic tank’.

Above the toilet:

A German health and safety poster showing a gas mask against a khaki green background, and in spiralling letters: ‘noxious gases and vapours threaten your life, wear aragen breathing aparatus!’

–

My uncle Dan, Palička’s son and the cottage’s heir, has made nearly all the decisions about how to decorate the house over the years. It’s a privilege he’s earned. He works in construction during the week and spends his weekends toiling from morning to evening improving the cottage’s fabric. It requires almost continual maintenance; all his leisure time is spent working through a list of urgent chores. This is such a common experience for cottage-owners – which a large proportion of Czechs are – that the Czech language has a specific phrase for it: aktivní odpočinek (active rest).

He parks his car one weekend and he’s immediately in the backroom workshop as usual, standing among a tangle of dangerous-looking wires, a tool in his hand, preparing to sand down timbers, repaint the sloping roof, unblock the plumbing, and strim the garden while Palička supervises, barking directions. Luckily Dan is suited to the challenge. He is practical, dedicated, solid. His generosity has no limits. Aged ten, he distributed all of Palička’s jewellery to his friends, dividing the pieces up fairly so each had the same portion; she had to call round all of their mothers and ask for them back.

Positioning myself at a safe distance from the wires, I ask him where all of the German memorabilia came from. Half turned to me, one eye on a dish of industrial paste that is curing rapidly, he tells me he used a Czech portal named Aukro to buy ‘Sudeten’ things. He collected them one by one over the years, favouring objects that were ‘not overpriced’.

In London, I log on, expecting to find an online antiques shop. Instead, I find it’s a place where you can buy almost anything, including second-hand cosmetics, broken electronics and dirty magazines. You can also purchase raw construction materials – no wonder Dan knows it. Chilli peppers in the top right-hand corner of product photos indicate the auctions that are ‘red hot’.

I search the word ‘Sudeten’ and turn up the following.

A black and orange fabric badge with scalloped edges and a figure holding the scales of justice surrounded by the words municipal office or jermanitz, a nearby Sudeten town renamed Jeřmanice after 1945. (for your collection!!! reads the description.)

A silver letter sealer with a black handle given to a German teacher by the pupils of ‘Class Five’ in June 1920, the end of the school year. Pressed into wax it would leave the imprint of the initials ‘BI’ surrounded by a circle.

A disability insurance card belonging to painter’s assistant Emil Klesatschke, dated 28 October 1942. His name is written with a typewriter over a set of close lines that look like the stave on sheet music. It’s all in German and the word Sudetenland – by that time Nazi Germany’s territory – is stamped in thick Gothic script at the top.

A packet of 45 images of empty gilt frames against a black background, from a catalogue of a defunct German framing business.

The vacant frames strike me as evocative – a heavy-handed metaphor for the void created by displacement. I put in a bid at the starting price. No chilli pepper pops up. Two days later, I win.

There is no shortage of scraps, bits and pieces of Sudeten German life, to supply the nostalgia market. Czech people doing up their cottages seem to turn up boxes and chests from attics, cellars, and outhouses almost constantly. There were so many possessions, the valuable and the valueless, that did not fit into the 30-70 kilogram luggage allowance in 1945. A letter sealer, insurance card, and marketing paraphernalia are exactly the kind of things you would leave behind when filling your rucksack in the early hours, watched over by neighbours who have turned against you overnight.

For the most part, the descendants of those Czech neighbours do not have any ties to the Sudeten German families whose homes they live in. So, why not sell their stuff? Without a family remaining to contain them – to wrap them securely in stories, associations, meanings – the left-behind objects have become curios. Oddities, rather than heirlooms. ‘Found – I don’t know where anymore. No one knows the family . . . ?’ wonders an Aukro seller aloud underneath a listing of a joint passport issued to a couple on 1 March 1939, fourteen days before Germany occupied Czechoslovakia.

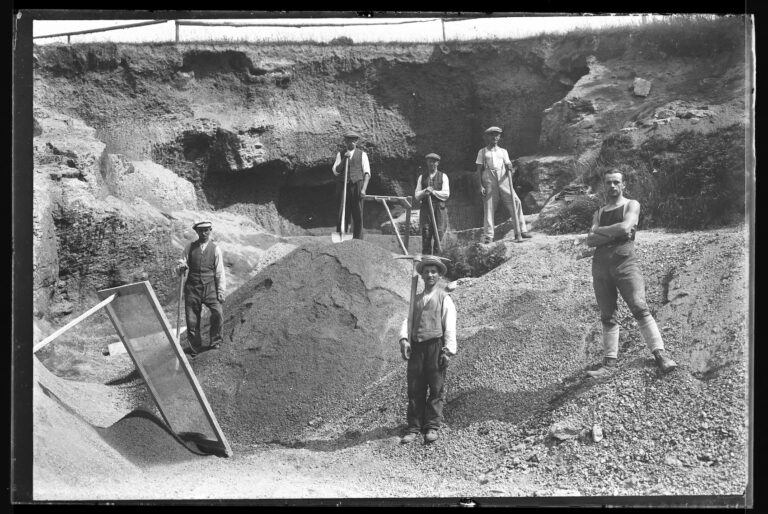

Dan tells me that in 2018 a box full of glass plate negatives from before the expulsion was found in one of the other cottages on Marian Mountain, and that one of the locals had them developed, thinking to turn them into a calendar. He later emails me a selection. The images are astonishingly sharp, unnervingly immediate, as is typical of this kind of photographic technology, which was widely used between the 1880s and the end of the 1920s. Some show local men at work, carving out gravel pits and creating clearings that I know well.

In one, a large family group – nineteen people altogether – are lined up outside the stripped-pine front of what looks like the cottage to the immediate right of ours. Perhaps Josef, Anna, or Elsa are in the crowd. It has the air of a wedding: the couple seated in the middle are clearly the centre of attention. The four girls kneeling in the front row are wearing pale-coloured dresses with extravagant tiered frills; one has a large white bow balanced precariously on her head. A boy on the far end looks unhappy in a bow tie and half suit. The men are drinking beer, the women schnapps from shot glasses. Some of the men balance cigars between their index and middle fingers. I wonder which of them were Nazi collaborators.

–

Scrolling the listings on Aukro, Nazi memorabilia from the occupation era appears now and again.

A postcard commemorating the ceding of the Sudetenland to Germany on 21 September 1938. A black-and-white painting shows four strong-jawed men standing among conifer trees, a Nazi flag with a swastika flying behind them. The SS soldier clutching a rifle in the middle ground is all uniform – a black void at the image’s centre. Above the group a mountain with an observation tower is faint in the distance. The reverse is blank; it hasn’t been written on.

A Czechoslovak stamp issued sometime in the autumn of 1938. It is light blue and shows a lino print of a bird carrying a flower in its beak. A swastika has been printed in black over the top and in German the words ‘We are free’. Price: 100 francs.

A white square ceramic bowl made in 1940. Reversed, its underside reveals an eagle looking over its left wing, its claws gripping a wreath, which surrounds a swastika.

The trade in Nazi antiques is thriving globally, as is the production of Nazi fakes. The Czech Republic regulates the display of Nazi items – unlike in the UK, flying a swastika flag is illegal, for example – but does not restrict their sale or ownership. Sellers on Aukro have developed their own weak, informal measures in an attempt to deter neo-Nazis. Many listings state sternly that the object has to be for personal collection and not used for ‘propaganda’.

The cottage contains only one such item. My dad noticed it during a green and humid summer, holding it gingerly in the tips of his fingers, arm extended to flap it in my direction while I sat in a wicker chair in the veranda, absorbed in something else: ‘there’s a Nazi newspaper here!’

I snapped at him instinctively, not liking to be disturbed, but also unsettled by the revelation, wanting to push it, and him, away from me.

The edition of Die Zeit is from 11 December 1941. An overexposed black-and-white photograph commemorates General Field Marshal Eduard von Böhm-Ermolli, an Austrian army general from the Sudetenland who fought in World War One and died on 9 December 1941. Another headline proclaims: ‘The Allies’ operational backbone has been broken’ next to a picture of a battleship.

Susan Sontag’s 1974 essay, ‘Fascinating Fascism’, outlines how Nazi fascism has acquired a kind of erotic power, how its world thrills and titillates. She looks through a cheap historical paperback that features unexciting pictures of Nazi officers’ uniforms, wondering why the run-of-the-mill photos of nothing much happening appeal. ‘For fantasy to have depth, it must have detail’, she concludes.

But Dan is not a neo-Nazi, nor are the majority of the people who fuel the market. Their intentions are not as clear, their desires knottier. The newspaper is not particularly treasured. It’s not a prize or a relic. It’s tattered, even though it is held in a newspaper stick like one you might see in an old-fashioned European cafe. The newspaper is not shiny, slick, or sexy – like the Nazi uniforms Sontag focuses on – it’s just there, heaped in with everything else, left to get worn, forgotten and then rediscovered. It’s powerful, but also abject.

–

‘I’m not an admirer of Sudeten Germans. Most were fans of Hitler’, Dan says, throwing a heaped spadeful of sand and gravel into the open mouth of an orange concrete mixer in the front garden.

‘I always took as a historical fact that they made a life out of the modest possibilities they had. Sudeten Germans lived their normal lives here, working, having children and dying.’ He’s leaning down, adjusting the speed of the rotating drum.

Twisting back to the white canvas bag for another spadeful: ‘I don’t think it would be right to pretend that this didn’t happen, whether we like it or not.’

What he says is the opposite of kitsch, although some of his house might look a little kitschy. I wondered at first whether his collecting habit was the easiest way to forget – to bring something into your home, where you get so cosy with it, cocooned by it, you can look at it without seeing. I understand Dan differently now. He is a historian, assembling fragments in order to make an account of the past. He has built for himself a new story, one that is not black or white, or about winners or losers, but rather that seems to hold the competing narratives close. Perhaps his generation finds it easier to think like this because, now that they are settled into their holiday homes, they do not feel under threat from revenants. Because of the circumstances – the binary divide between ‘good’ (Allies) and ‘evil’ (Nazis) – the displacement of Germans in 1945 has been accepted, whereas other ethnic cleansings have not. It would likely be repeated in the same way tomorrow, should the same war take place.

I leave Dan beginning to shovel the wet cement and walk into the living room where Palička is laying sliced mushrooms out on sheets of newspaper to dry, humming to herself loudly. On the wall, above the dining table:

A floral metal plaque with a brown background that says, in black German gothic script, ‘Mag draußen die Welt ihr Wesen treiben, Mein Heim soll meine Ruhstatt bleiben’ [May the world outside go on, My home shall remain my resting place]. The letters are surrounded by rich purple petals that look as if they might bruise if you touch them.

Images courtesy of the author