‘Xenotransplanting,’ the rat repeated. ‘That’s some ugly mouthful.’

‘Oh they’re very excited about it,’ the horse said moodily. ‘They say it’s a real game-changer with little risk to society.’ He was an entire horse – not a day went by that he didn’t thank his lucky stars for that – but he was a nihilist too, although an anxious one.

‘Everything’s a game to them and the game is making them crazy,’ the rat said. His name was Victor. All the rats were called Victor after the ubiquitous trap. A bit of black humor came down through the generations.

‘Wilhelmina will be spared,’ the horse said. ‘That’s the good news. The bad news is that her offspring will be genetically edited to become reliable if unwilling organ donors. Your heirs, Victor, will be genetically programmed to suffer only as usual.’

‘Whatya mean?’ Victor said. ‘I want them to enjoy a proper lifestyle. Kitchens. Dumps. Fairs.’

‘No more fairs,’ the horse said. ‘They’re going to schools. Probably not Harvard.’

‘Why not Harvard!’ Victor said, insulted.

‘Maybe Duke,’ the horse said.

‘Pray that they don’t go to Tulane,’ the sheep said. ‘Isn’t that where those unfortunate monkeys went? Very badly handled.’

‘The spinal cord does not regenerate,’ one of the spiders said. ‘You’d think they’d have learned that by now.’

Wilhelmina trotted into the barnyard. She was Some Pig. Her eggs easily incorporated the human genetic code. All her piglets were star patents. But she often worried about their lack of engaging pigness – they looked a little blank to her. They had these disturbing one-yard stares.

‘Your issue will be increasingly engineered with specific maladies, Victor,’ the horse went on. ‘Tumors, leukemia, Alzheimer’s . . .’

‘Something akin to Alzheimer’s surely,’ one of the spiders said. Charlotte’s children possessed her looks and intelligence but sadly not her creativity. They were widely traveled though they made very careless webs. This was not entirely their fault, however, as environmental factors were no longer conducive to their inherent skills.

‘. . . enlarged prostates,’ the horse concluded wearily.

‘No one wants leaner or tastier meat from us anymore,’ the sheep said. ‘Or rather they want that too but they particularly want our organs – our sister pigs’ hearts especially. They’re having more and more difficulty with their own hearts so they want ours.’

‘But our hearts belong to us most of all, don’t they?’ Wilhelmina said.

‘It’s taking the eyes, our beautiful eyes, that is so distressing,’ the sheep said.

‘Xenografts,’ one of the spiders said. She thought she’d spell it out but then thought, oh why bother.

‘I feel faint,’ Wilhelmina said.

‘Wilbur cozied up to the humans too much,’ Victor said. ‘That’s why we’re in this mess.’

‘It was those buttermilk baths and being wheeled around in the baby carriage,’ the sheep said. ‘Wilbur was a little . . . how shall I put it . . .’

‘That Charlotte was a piece of work though,’ Victor said. ‘What a gloomy broad. Remember those lullabies?’

‘ “Sleep, sleep, my love, my only / Deep, deep, in the dung and the dark; Be not afraid and be not lonely!” ’ Wilhelmina murmured.

‘Yeah,’ Victor said.

The others looked shyly at Paul and Priscilla, the silent calves who had been cloned from the meat of their butchered mothers.

‘I prefer the Tennyson poem,’ the sheep said. ‘I find it more hopeful. May I?’

Victor smirked. She was one affected ewe, always pretending she was from the Emerald Isle and just visiting this barnyard.

The sheep began:

O yet we trust that somehow good

Will be the final goal of ill,

To pangs of nature, sins of will,

Defects of doubt, and taints of blood;

That nothing walks with aimless feet;

That not one life shall be destroyed,

Or cast as rubbish to the void,

When God hath made the pile complete;

Paul and Priscilla turned away, like ghosts.

‘I feel so sorry for those kids,’ the goose said.

‘What does he mean by pile?’ the horse asked. ‘Pile seems a rather careless choice.’

‘Just rhyming, don’t worry about it,’ Victor said. ‘Remember the fish story? When Charlotte caught the fish?’

‘But it’s not the pile that rhymes, it’s the feet with complete. Do you think he meant . . .’

‘It was her cousin who caught the fish,’ the goose said.

‘Whatever. What’s a fish doing jumping up and getting caught in a spiderweb in the first place? Was it a salmon? All those PCBs make them kind of weird. There was something wrong with that fish.’

‘Charlotte was exercising poetic license,’ one of the spiders said. ‘Speaking of stories did you know that Ludwig Wittgenstein was reading Black Beauty when he died?’

‘Really?’ the horse said.

‘I don’t know if he was in fact reading it, but they say it was on his bedside table.’

‘A wonderful book,’ the horse said. ‘It promoted kindness and sympathy and the worth of all creatures.’

Kindness, sympathy and love, one of the spiders mused. Without them man is nothing. Perhaps . . . ? She looked at her sisters entombing a fly. But it would take so long to compose this sentiment in separate webs and didn’t the pest control service come at the end of each month?

‘Nobody writes books like Black Beauty anymore,’ the horse said.

‘I hate to tell you kid,’ Victor said, ‘but you were never in this book either, the one you think you’re in now.’

‘I am,’ the horse said morosely.

‘It’s a dream kid. You don’t exist.’

‘But I do,’ the horse said.

‘You were collected running free on the great lands of the American West, dumped in a corral and trucked off to the slaughterhouse.’

‘Oh it was awful, awful,’ the horse said trembling. ‘But what did we do to warrant such horror?’

‘You ate grass didn’t you,’ Victor said. ‘You were taking up space.’

‘This is all so frightfully depressing,’ Wilhelmina said.

‘At least your little ones are respected symbolically,’ the goose said to the sheep. ‘Not that it matters in the end of course.’

‘Yes yes,’ the sheep said fretfully. ‘Symbolically we feel quite honored, well somewhat honored.’

‘Our creaturely kingdom is being slaughtered daily, hourly, without a qualm on their part. And now we will be sacrificed for even more extreme adventures,’ the horse said. ‘They are the brutes of the cosmos.’

‘Won’t the children save us?’ Wilhelmina said. ‘Won’t the children stand up for us?’

‘I dunno,’ Victor said. ‘They seem a little distracted. Or hypnotized or something. Always staring into those white screens.’

‘I simply can’t believe the things I’ve heard and that we are discussing this very moment,’ the sheep said. ‘It’s simply too insane and totally unwarranted.’

‘Are they not thinking?’ Wilhelmina said. ‘I don’t think they’re thinking.’

‘I was once told that if people acted as certain insects do they’d possess a higher intelligence than they do at present,’ one of the spiders said.

‘It’s all illusory,’ another spider said. ‘Maya.’

‘I fear it really isn’t,’ the horse said.

‘I wish I had that name,’ said the third spider.

‘Why don’t you then!’ Wilhelmina exclaimed. ‘You can. Why don’t we forget all this gloomy talk and have a naming day for . . . MAYA . . .’

No one responded, not even the little spider who didn’t have a name.

‘This is the life we’ve been given and our children as well,’ the sheep said, ‘but why do they take it away so cruelly and with such horrible fascination and delight?’

‘Some say that if they didn’t utilize us, murder us for this and that, they wouldn’t allow us to be at all,’ the goose said.

‘But wouldn’t they miss us?’ Wilhelmina said.

‘I don’t think they would. They’d find a way around missing us,’ the horse said.

‘They’re so clever,’ the sheep said.

Victor loudly burped.

Be not afraid and be not lonely, Wilhelmina thought, but couldn’t bring herself to say it. She wanted to reflect on her pretty piglets but night had fallen and she and her friends were once again hopelessly caught up in trying to comprehend the terrible ways of men.

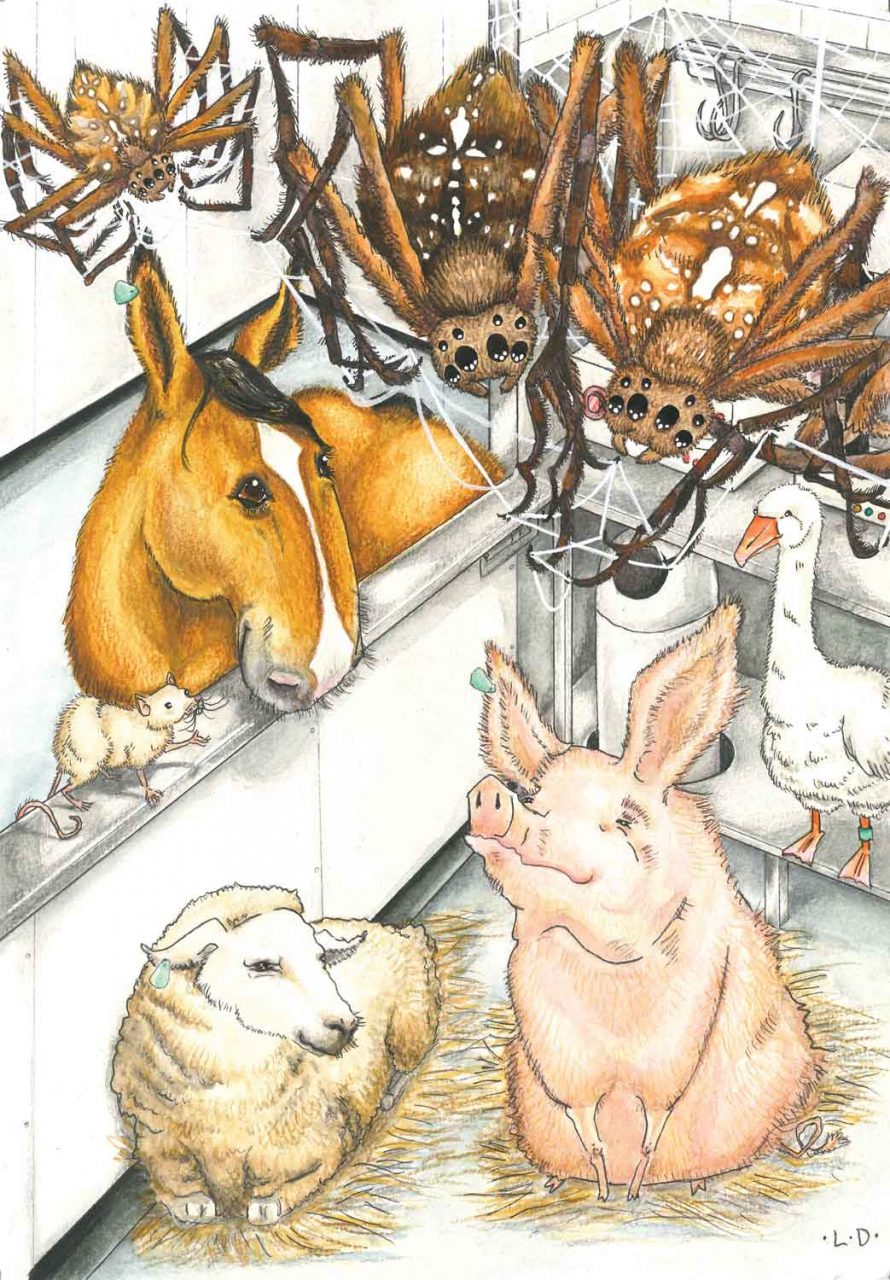

Illustration © Lucy Ducker