This is a story I’ve heard. I’ve no way of knowing for sure, but I think it’s true.

1946. Calcutta is a city ripped apart like an old sari. Hindus and Muslims are hacking into each other, the attacks coming in uneven wave and counter-wave. All the authorities can do is clamp down a citywide curfew, allowing people a window of two or three hours to get their supplies. On a hot day, during the hours when movement is allowed, a man of about thirty goes out to meet a friend who lives nearby. On his way back through the deserted streets, he sees two teenage boys pelting out of a side street, leaving a trail of blood behind them. The boys see him too, and start with terror. Then they see that he is alone, that he isn’t about to chase them. They take a chance. ‘Please sahab, please save us!’ The man is a middle-class Hindu, you can tell from his dress: a white dhoti flowing out from under the long, loose shirt called a kurta. The boys are Muslim and poor, you can tell from the simple, checked lungis wrapped around their waists. Whatever they were wearing on their upper bodies is torn to shreds, and there are fresh wounds bleeding. One of them is limping from where a blade has caught his foot.

The man tells them to stay close and walk behind him. He knows there is a hospital half a mile away where they are taking in riot victims from both sides. He also knows that the half-mile is completely Hindu and Sikh territory – it’s his own neighbourhood. He walks forward, hoping nothing will happen, and the boys follow.

The man is a Gujarati, from the west of the country, and he has settled in this part of town, which has a shared concentration of Gujaratis and Sikhs – immigrants too, but from the north-west of India. The two communities have in common their strict vegetarianism and a willingness to leave home and go anywhere on the planet to make a living. What sets them apart, however, is important: the Gujaratis are mainly businessmen who go to great lengths to avoid physical labour and physical altercation while the Sikhs, the Sardars, are from peasant stock, not shy of hard manual work, and belong to a religion that was forced to give primacy to the sword; as they see themselves and as the world sees them, if ever a man was born to be a warrior it was a Sardar. There is a joke: just as a Sikh is supposed to have his kirpan – his religious dagger – with him at all times, so a Gujarati never lets his accounts book stray too far from hand.

As the man and his wards cross a street of mechanics’ garages, their worst fears suddenly become reality. Five Sikhs are walking towards them, two of them with long swords, the rest with their kirpans on their belts. The boys look to run but they know they are trapped. The leader of the Sardars comes up to the man in the white dhoti.

‘Babuji, where are you taking these vermin?’

‘To the hospital. You can see they are hurt.’

‘Please move aside, Babuji. These two are not going to need a hospital.’

The word ‘Babuji’ implies all the class-respect a taxi driver or car mechanic would give a middle-class customer, but there’s no mistaking that the Sardar means business.

The man stands his ground. As the Sardar starts to go around him, he steps sideways, keeping himself between the Sardar and the boys. ‘They are hurt badly enough. Now stop. All this has to stop.’

‘It will stop when they are all dead. Each and every one of these dogs.Then we will stop.’

‘No. You will stop now.’

‘Babuji, I will kill you if I have to, but there is no saving these dogs.’

‘You will have to kill me first.’

The words are out of the man’s mouth before he knows what he is saying, but they only define what his body is already doing. It is near noon and the shadows are small, hard, black puddles around the men’s feet. The two boys are clutching each other and shaking, and their shadows are joined together over the blood they’ve smeared on the road.

The Sardar’s calm demeanour explodes. The postcards describing what’s been happening back in western Punjab, in Lahore, in Sialkot and Rawalpindi catch fire in his eyes – the raped girls, the slaughtered cousins, the burned farms. In his mind, only the Sikhs have suffered, and the Hindus; in his mind there is not a single Muslim woman dishonoured, not a single Muslim baby skewered and thrown into a well. As the other four spread out to catch the boys when they run, the leader’s sword arm goes around and up, as if he’s about to hit a hard backhand in tennis. The sword is not new or shiny – it is dull even when it catches the sun – but it looks sharp enough.

‘Move, I tell you!’ The Sardar is shouting now, all respect gone for this man who would protect these poisonous creatures over his own sisters. Two dead or three, the sword wouldn’t know the difference; one Hindu but then two of them, the sword would feel no guilt; one more swing of the arm in these endless days and nights of many strikes, his arm will feel no more tired than if it was just the two boy-rats.

The sword quivers for the last time, sucking up the energy it needs to come slicing down. The man straightens his back, looking for the right kind of final prayer. Every time I hear the story, I start to pray too: God, please don’t let him bring the sword down, please don’t let him kill the man who will become my father.

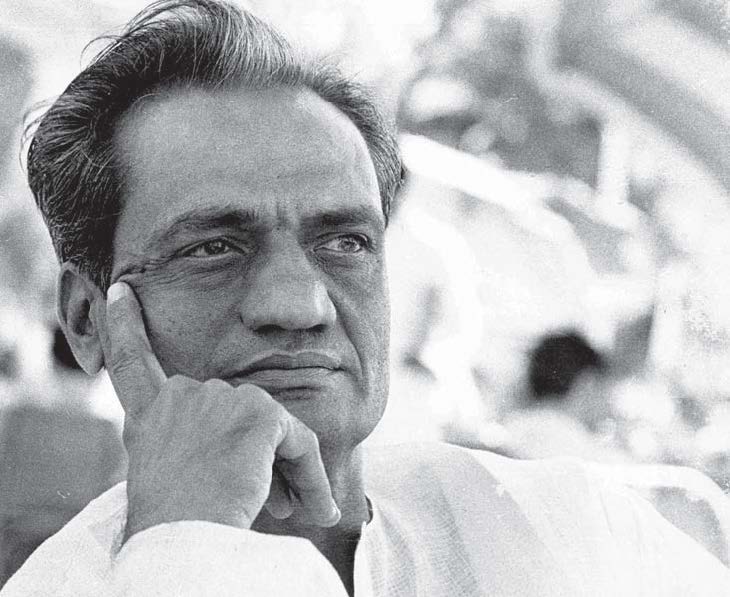

Shivkumar Joshi, c. 1972

With my mother, the story would often start backwards. When the man who had not yet even imagined me got the boys to the hospital on Elgin Road, he took them to where they were keeping the Muslim wounded. The section was as far away as possible from where they were keeping the Hindus. As the boys ran into the compound, the man in the dhoti waited to see if they were going to be looked after. I don’t think he was waiting for any gratitude from the boys, his own thanksgiving at still being alive was crowding his head. What he didn’t expect in the haze of relief was what the two boys actually did, for them to turn around and point to him, shouting ‘Saala Hindu hai ! He’s a Hindu! Get him!’ It took the man a few precious seconds to overcome the shock as the crowd surged towards him, but he managed to escape.

If there was any trace of self-gifted heroism in my father’s recounting it would always be leavened by this last kick in the tail – how stupid could he have been, why couldn’t he have just turned away at the hospital gate and left the two bleeding boys to their fate? How naive could he have been about what was going on? He would have understood if they had run into the Muslim section and disappeared without a backward look, they had barely escaped with their lives; but where did they find the reservoir of hatred, the energy to turn around and try and get people to attack him, the man who had just risked his own life to save theirs?

‘Ek laafo maarva nu munn thhaay! ’ – ‘One really feels like giving them a slap!’ my mother would say, when she actually meant she felt like killing them.

A mixed neighbourhood of Gujaratis and Sikhs. An older Gujarati lady looks down and sees someone she knows, Shivkumar Joshi, a nice young Gujarati man, about to be beheaded by the Sikh owner of a car-repair garage, a man she also knows.

‘Ei Sardarji! What are you doing? He is like my brother!’

My father always described it as a lifesaving shriek. Maybe it was a scream, maybe actually a calm, strong calling out. Whatever it was, it worked. The woman, for whom my father was like a brother, was also ‘like a mother’ to the man holding the sword. So he stopped, and so did the others. With the greatest reluctance they let the two boys go, along with the fool protecting them.

‘I still don’t see why Puppa needed to do that!’ After all those years, my mother was still angry with my father for having risked his life. ‘It’s fine to be brave, but really, your father was actually saved by Ma Durga herself, coming in through that lady. Those Sikhs can be very violent – they would have killed him for sure!’

‘Don’t you want to slap them as well?’ I would ask, gleefully imagining my mother laying into five strapping Sardars.

When I was a kid, parents regularly slapped their children. It was a standard mode of discipline and chastisement, sealed off from any deep thought or excessive premeditation. Like Eskimos with their thirty-two names for snow, we had many different names for aggressive hand-to-face contact, the variations and degrees demanding precision: for instance, the mild finger-flick was a ‘lappad ’, a proper palm landing on cheek was a ‘laafo’ or a ‘thhappad ’, whereas a full-force forehand catching someone on the ear and sending them flying was, in my parents’ language, Gujarati, a ‘dhhawl ’.

The time was the 1960s and the slap was a kind of behavioural coin of the realm. Heroes in films slapped villains, employers slapped servants, cops slapped rickshaw-pullers for traffic infringements, teachers smacked students, husbands lit into wives and parents hit children. India was only a few years old then and it was a country trying to slap itself into becoming a nation. The slapping was the mildest tip of the iceberg, of a whole, immovable Arctic shelf of violence that lay under the pictures of Mahatma Gandhi and the pomp and ceremony of a state that proudly proclaimed its non-violent antecedents while still trying to stem the deep wounds of the mass bloodletting that had been the price of independence.

A vague awareness of the larger violence taking place all around didn’t help much while dealing with the daily danger of assault from parents or teachers. When I was six, I witnessed a teacher draw blood when she flung a wooden duster and caught the kid next to me on the forehead; she apologized profusely to his parents and went back to plain slapping and spanking the next day. Most teachers hit us, but at home things were different. Boys usually caught it from their fathers and went running to their mothers for comfort. In my family of three, however, the main turbine for generating punishment was my mother. Any mischief would be met with a ticking-off, any escalation then countered with a lappad or a thhappad; the dangers of having sporting equipment lying around were also brought home to me when my mother once deployed a hockey stick, and another time a cricket stump.

In the first ten years of my life, my mother did ninety-nine per cent of the hitting but also most of the loving. My father slapped me exactly three times and I remember feeling like I’d deserved it. They were hard slaps, thhappad but dangerously close to dhhawl, and they hurt like mad, but there was no residue of rancour and so they didn’t fester in me like my mother’s punishments.

With my mother a slap had as many meanings as it had names: there was a fear of losing control, there was frustration at the actual loss of it, there was an anger towards the world in general and there was sometimes a sense of betrayal, when the love she gave me wasn’t reciprocated as she wanted. On the other hand, the three slaps escaped from my father despite himself. It wasn’t as if there was a whole army of them simmering inside him; I’d crossed a line beyond tolerably annoying and got whacked, and that was it, it was over, with both of us equally shocked. Afterwards, I could see he deeply regretted hitting me; what I could not see was that he was saving his anger and fight for other things, things that mattered, things that could not be sorted with a slap.

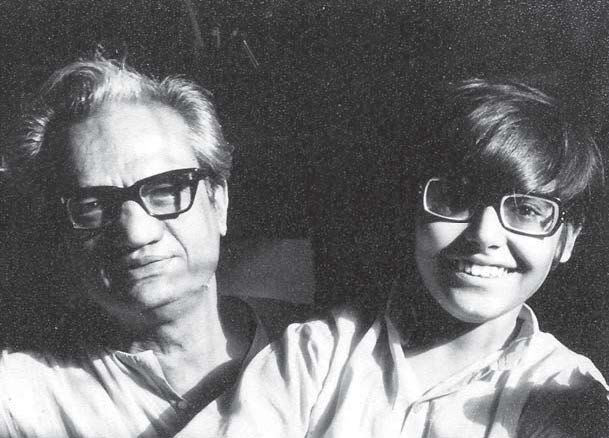

Satyavati and Shivkumar Joshi, early 1960s

Both my parents were blessed with warm, loving hands. I was their only child and they made sure I knew just how wanted I was and how loved. I still can’t figure out how that love communicated itself through touch, or how that touch has managed to live on inside me. Equally, I can’t understand how my father managed to be both affectionate and yet distant; why there is such a distinct difference between my mother’s touch and my father’s in my sensory memory.

Though we didn’t talk much in my early childhood, I was very physical with my father. We’d hug, we’d shadow-box, we’d wrestle. Once, when horsing around, I flailed at him with my foot and took out a front tooth – there was hell to pay, but entirely from my mother shouting at the two of us while my father defended me through a cloth held to his bleeding mouth. I still remember him coming home, grinning, with the gold replacement, and my mother berating me about how much the dentistry had cost. I didn’t pay it much mind. It was only Puppa, after all, and not some vengeful teacher that I’d kicked, and it was only Mummi, who shouted a lot anyway.

Because he’d told me a few stories, I knew that as a teenager Puppa had worked out on a ‘malkhamb’, wrestled and played tennis. The malkhamb was a smooth, iron pillar you found sticking out of the sand in traditional Indian gymnasiums, usually about ten feet high and about three and a half feet in circumference. The idea was to strip down to the barest loin-covering, oil yourself all over and use muscle and speed to twist up to the rounded head of the pillar; once on top, you did slidy, oily gymnastics before working your way down again. This crazy malkhamb and the wrestling gave my father muscles that he retained well into his fifties. For me the curious thing was that along with the hard muscles went a deep adherence to Gandhi’s philosophy; whether the country did or not, my father certainly took the idea of non-violence very seriously. Whereas a lot of his earlier gym-mates had turned into Hindu fascists with grandiose and vicious ideas of Hindu supremacy, my father had become a Gandhi-ite, thrown away his Brahman’s sacred thread and tried to stick as far as possible to the Mahatma’s creed.

For my father, non-violence meant avoiding violence as a first, second or even third choice but not always and under any circumstances. As I grew to know him, I saw that courage and immovable quality as central to his being. But as a kid I was confused by him. He was mild-mannered and yet solid. He lost his temper only about once a year, usually with a shout that could have shattered wood, causing everybody to dive for cover. Otherwise, he had infinite patience and great tolerance of all kinds of stupidities that would send me or my mother over the edge. Even the solidity was leavened by the way the man held himself, by his grace and by the way he dressed.

He was an unusual father in many ways and this was reflected in his appearance. At home, Puppa would wear the normal loose kurta and pyjama worn by a lot of Indian men. It was the going-out clothes that were different.

Most other fathers wore ‘shirt-pants’, the ubiquitous 1960s combo of bush shirt and trousers and, from the late 1970s, the ghastly safari suit, the power-dress favoured by everyone from industrialists to Indira Gandhi’s ‘Black Cat’ security detail; some daddies who worked for foreign companies wore proper suits, some wore shorts on days off and made like they were in Israel or Virginia. My father’s own business was totally dependent on the aspirational and affluent urban Indian male’s desire to dress like a Westerner; he was the representative in eastern India of textile mills on the other side of the country that manufactured ‘terelene’, ‘tericot’ and other cloth made with polyester yarn content. Though he spent a lifetime selling it, my father hardly ever let that synthetic stuff touch his skin – on most days he wore a crisp dhoti and kurta made from the roughest khadi, the handspun cotton cloth Gandhi had made legendary. The dhoti would take a full three minutes to put on, with the different folds and layers being wrapped around his legs and then the final pleating making a fan that flowed down the middle to the ground. The ganji – the sleeveless vest – also made of khadi, would go on next, and then the starched white kurta. Within minutes the ironed kurta sleeves would be rolled up but the rest of the creases remained intact throughout the hot, fetid Calcutta days, coming back remarkably unscathed from one of the few workplaces in Badabazar market still without air conditioning.

In the line-up of adults in my head, there were women, who all wore saris, there were men whose signature was the shirt and pants, and then there was Puppa. Even though I saw my father as a ‘tough guy’, to my mind this dhoti and kurta were not a fighter’s clothes. Western film-warriors wore pants and hats and gun belts; Indian mythological figures did have dhotis but they were tightly wound around the legs so that they were almost trousers, nothing that would get in the way of drawing sword from scabbard. My father’s dhoti- kurta undercut all this in ways I couldn’t figure out – he somehow managed to look feminine, graceful and manly all at the same time; no matter what others thought, he was completely assured in his own definition of masculinity and Indianness.

When I heard stories of his generation facing the policemen deployed by the Raj, I often wondered how these ‘freedom-fighters’ managed to avoid tear-gas canisters, run, jump across roofs and escape from cops in proper battlegear; but by the time I was about eight or nine I noticed the agility people like my parents had while dancing the traditional Gujarati dances of garbo and raas. My father was very active on the Calcutta stage, directing plays in Gujarati and Hindi, and during rehearsals I saw how quick-footed he could be, leaping from the front aisle on to the stage to make an adjustment to the blocking or the set, all wearing the same dhoti-kurta.

As a privileged child of modern India, wearing my shorts and sports shoes, and later my bell-bottomed jeans, it was difficult for me to understand, but gradually I began to accept that the dhoti-kurta was part and parcel of my father, that any other dress would be wrong. Whenever I’d ask him about his clothes, he’d reply: ‘These are the clothes in which I’m happy. You shouldn’t change your nature to suit fashion.’ His trousered friends would rib him about the irony of a man in traditional khadi trying to convince people to buy polyester suitings but it wouldn’t make any difference – business was just business, to stand in for religion my father had other passions.

Written in English, ‘Mummy’ and ‘Papa’ don’t convey the actual names I called them.

There were, of course, many different names for ‘mother’ and ‘father’, and each set came embedded with morals and social weight, usually explained to me by Mummi. There was the commonly used ‘maa’ and ‘baap’, which worked equally in Gujarati and Hindi and cut across all classes – even the poor had one each; there was the Bengali ‘ma’ and ‘baba’ (confusing, because ‘baba’ was also the Gujarati/Hindi word for ‘baby’ and ‘child’); there was the slang we used among us kids, lifted straight from American comics, ‘Mom’ and ‘Pop’ (amusing in the family, but God help you if you used either before visiting relatives); and then there was the super-formal, Sanskrit ‘matru’ and ‘pitru’.

What I called my mother was a very Gujarati ‘Mumm-ii ’. The ‘Puppa’, too, was an address typical of modern, urban Gujaratis and not the Anglo-Saxon/French ‘pa pa’ nor the Italian/Punjabi ‘paa-pp-a’, but ‘Pupp-paah’, the first syllable more or less the same as the word for baby dogs. The names came with a hierarchy that was instilled early and it remained unchanged: even though both my parents are gone, ‘Puppa’ is still attached to a respectful and formal ‘tamhey’, while ‘Mummi’ is always locked to a familiar ‘tu’.

I questioned this ranking early on and I remember yet again coming under the wheels of Mummi’s inexorable rule-chariot. ‘That’s just the way it is. No you cannot call Puppa “tu”! And you call me “tu” because I am your maa and you love me!’ It did not occur to me to ask whether I loved Puppa. Clearly, mummis were for loving while puppas were chiefly there to be respected.

It was my mother’s job, as Comptroller of All Seriousness, to pass on to me the basic cultural building blocks Hindus call ‘sanskaar ’. The word means, simultaneously, traditions, morals, graces, manners; a kind of cultural sixth sense that needs to be both hard-wired and programmed into one’s child. It was always my mother’s project to imprint upon my being the strictest sanskaars she could – nothing less would befit a child of her and my father’s lineage. A sanskaar could include basic instruction – dos and don’ts, sayings or Sanskrit shlokas (specific chants meant to be incanted at different ceremonies). One that my mother repeated often, especially when I was cheeky or rude to her, was ‘Matru Deivo Bhavaha… Pitru Deivo Bhavaha…’ – ‘Treat thy mother as a god, as a god treat thou thy father…’

Besides trying to convince me to treat her and my father like gods, my mother also took recourse to English sayings and phrases to bolster my fledgling character. ‘Your father is the Head of the Family,’ was one she would repeat, when I could plainly see this was not true. My mother was not designed to be bossed by anyone and it was probably one of the main qualities that had attracted my father. Throughout my childhood, Mummi took all the decisions: she didn’t drive but she was the one who decided about buying our first car; she never took photographs but she deployed the money to get my father an expensive Nikon; she controlled all the toys and books I had; she managed all food and household help; she had initiating powers and final veto on holidays. Puppa may have been the titular head of the family the three of us made up but, in the day-to-day, Mummi was the General Officer Commanding.

Though he had very clear ideas about sanskaar himself, my father never tried to drill them into me. By the time I turned twelve, the usefulness of slaps and dhhawls was long over, not that Puppa had much favoured these; by that time he had watched my mother’s frustration smash against the rocks of my intransigence for nearly ten years and he had drawn his own conclusions. When it was his turn to take charge, he was smart. He was also a straight-talker, so there was no attempt at those favourite parental techniques, subterfuge and manipulation. He decided I was old enough and he began a conversation with me.

‘It says in the old texts that a son is a child from birth till the age of eight and you should treat him gently. Then, from eight to the age of sixteen he is your son and should be treated firmly, but with love. From sixteen he is no longer your son but your friend – if a man is wise, he should have turned his son into a friend by the time he reaches sixteen.’

It was a pretty bold laying out of what he wanted. As far as I knew, none of my friends’ fathers had ever said anything like this to them. It did away with all the smoke and mirrors of patriarchal power and it was a softly-spoken challenge both to me and to himself – let’s try this, because it’s the only thing that will give us a relationship worth the name.

But then my father had experience of other models that hadn’t worked, models laced with violence that wasn’t always physical. His own father, my Dadaji, was a scary figure who cracked the whip over a huge family; in my mind, he competed for the Cruelty Cup with other psychopathic Heads of Families who ruled that class and caste in early twentieth-century Ahmedabad. My father was the fourth of eight children who hardly seem to have spoken to the man they all called ‘Mohta Bhai’, literally, ‘Big Brother’. If a child was reported for a misdemeanour, serious naughtiness, a bad school report or having been caught at the cinema, Mohta Bhai would call down from his study:

‘Shivkumar!’

‘Yes, Mohta Bhai.’

‘Come up here.’

`Yes, Mohta Bhai.’

‘And bring the cane with you.’

And so my father would have to climb up the stairs to the landing where the cane was prominently suspended, take it off the wall and carry it up to his father. The canings hurt but having to deliver and then take away your own instrument of punishment seemed to have left a deeper wound. This strict ‘discipline’ left scars, but they were nothing compared to what followed. Coupled with the gross despotism in my grandfather was a disdain for any feelings and desires his children might have: their life-pairings were decided well before they reached anywhere near the supposed Age of Friendship. By the time they were eleven or twelve, my father and his siblings, both older and younger, were committed to marriages with equally prepubescent spouses, chosen according to precise sub-caste and in terms of strategic societal alliances. My father and most of my aunts and uncles were forced into disastrous marriages with failure, tragedy and oppression cemented deep into the foundations; my father’s youngest sister was the one exception, with a long and happy marriage; my father was the only one who eventually escaped, fighting and scrapping his way out of this self-perpetuating trap of dutiful, deadly matrimony.

My grandmother died when she was forty-two, sixteen pregnancies (including eight miscarriages) taking their toll. When my grandfather, then in his fifties, took a sixteen-year-old for a second wife, my father was the one who protested. Mohta Bhai’s retaliation was to pull the educational rug from under Puppa and send him to coventry in Calcutta, away from Ahmedabad and away from the girl he loved, Satyavati – Satu – who would one day, nevertheless, manage to become my mother.

My father did marry Sunanda, the girl he was ordered to, but not without a fight. He asked her first to release him from the agreement (as if she had a say) and, when she refused, informed her she would be marrying the equivalent of a corpse. He was eighteen then and she was probably no more than fourteen or fifteen; they married when they were a bit older. After the marriage, Shivkumar spent most of his time in Calcutta, working in his uncle’s business. For a few years, he refused to join his wife in bed. Whenever he needed to return to Ahmedabad he would sleep on the veranda of the large house Dadaji’s whole family occupied.

The one thing my father looked forward to on those trips back to Ahmedabad was meeting my mother. They would snatch time cycling on the streets or talking in tea shops. If my father was imprisoned in his marriage, my mother too was trapped in her life, supporting her mother and brother by tutoring rich mill-owners’ wives and daughters as she put herself through college and started a career as a teacher. By the time she was twenty-seven she had become the principal of the most prestigious girls’ school in Ahmedabad.

Much later, when I was in my twenties, I summoned up the courage to ask my father the one question I’d always been scared to approach: ‘So, Puppa, if you were so determined not to consummate your marriage with Sunandaben, how did you end up having children with her?’ Puppa laughed and said, ‘Ask Satu.’ The answer Mummi gave me was stunningly simple: ‘Sunanda came to me and asked me for help. I told Puppa he had to stop being stubborn and accept his marriage.’

The acceptance led to three children, my sister and my two older brothers. It also, I suspect, sharpened the reality for both my parents that this was the wrong marriage. After nearly twelve years of longing, twelve years when my father was mostly in Calcutta while my mother was nearly two thousand miles away to the west in Ahmedabad, the gap bridged by fragile and frequent letters, my parents decided to take a leap. In an operation involving great secrecy, double bluffs, early cross-country airline services and a small camera to capture documentary proof of the ceremony, with a sole friend as guest and witness, they pulled off their long overdue wedding. The year was 1952, and their marriage just squeaked in under the wire being laid down by Parliament – the Marriage Act – which forbade Hindu men from having more than one wife where previously they’d been allowed two.

There was no question of a divorce; Sunandaben wouldn’t hear of it, and in those days, there were no unilateral grounds for the nullification of a fully consummated marriage with three ‘issues’ as evidence. Neither would my father’s family, in whose business he was embroiled, stand for it, my grandfather’s own shenanigans notwithstanding; and my mother, now being a school principal and a paragon of morality and virtue, wouldn’t be able to retain her job. All of Gujarati society would see it as a scandal. QED, a proper marriage it had to be, both in the beady eyes of the law and the all-seeing eyes of the gods and goddesses, but it also had to be a union that was kept secret for the time being.

Whatever the status of his second marriage, it’s now clear to me that my father minimized his interaction with his first wife after their third child was born. Shivkumar would meet his children on his visits to Ahmedabad, which were twice or thrice a year, and sometimes they would visit us, but for about two decades he completely stopped talking to their mother. There was a small apartment he’d bought them, and their daily life and education were all paid for by him, but there was little of the kind of contact I, his fourth and ‘only’ child, took for granted. I remember watching his exchanges with my sister and brothers, by then all in their twenties, and they were of a quiet, affectionate but basically distant nature. They called him not ‘Puppa’ but by the name his whole family used: ‘Sara Bhai’, which means ‘Good Brother’. It was a direct link to the dreaded Mohta Bhai and his moats of formality, and traces of that patriarchal distance were clearly visible to me as I grew older and understood how privileged and rare my own relationship was with my father.

Despite his rejection of the way his own father brought him up, Puppa had been incapable of making himself the kind of father he wanted to be for his first three children. This is all conjecture, of course, but my guess is that my father’s default mode of parenting was an extremely benign version of my grandfather’s. Neither Mummi nor Puppa are around to contradict me, nor too many of the friends who were witness to our family at the time, but examining my memories of the first decade of my life tells me that the odd bout of wrestling and clowning around were counter-intuitive. He was fighting his own programming.

I didn’t buy any of the Pitru deivo bhavaha stuff, but as a young boy I did see that there were actually three or four Puppas. One was the crumpled pyjama-kurta man who read the newspaper, drove to the market and helped me with my arithmetic; one was the man who dressed, went to the office and made money; one was the man who was into theatre and laughed and joked with friends; and then there was the well-known Gujarati writer, the man who gave speeches, attended conferences, won awards and was respected by all sorts of strangers in Calcutta’s literary circles, and much more widely on our visits to Bombay and Ahmedabad.

The crumpled-kurta Puppa would sit at home, hugging his desk, rapidly scratching away with his thick-nibbed fountain pen; the small, square, unlined notebooks would pile up until there were ten, twelve or fifteen of them and then copied into ‘fair’; then packed in cloth, sealed with wax and sent off to Bombay via the ‘dadukias’, the traditional business couriers used by Gujaratis, who carried anything – cash, bonds, jewellery, documents and deeds – no questions asked, no delivery ever failing. The publishers employed one man whose chief job was to decipher the handwriting of a Shivkumar Joshi manuscript when it arrived. This man would transfer the text to hand-run typesetting and letterpress, and the proofs would duly come back for my father to correct. One day a big brick wrapped in thick brown or white paper would arrive; my father would tear open the wrapping and present my mother with the first copy of his latest book and my mother would proffer the book to her picture of Krishna. From this activity came the man everyone knew as the ‘lekhhak’ – the writer – Shivkumar Joshi, who sometimes stood on stages to speak and to receive garlands, a formal shawl draped over his shoulder. By the time he died, my father had published over ninety books (many quite slim, a few quite fat, as I divided them then), of novels, short stories, plays, essays and travelogues.

When he was young, my father had wanted to be a painter but Mohta Bhai would have none of it. ‘No son of mine is going to become a paint-slave!’ Gujarati is probably the only language to have a derogatory word for ‘painter’, the word my grandfather actually used – chitaaro. My father did paint occasionally, but the regular hunger to produce images transferred to his photography; the many narratives he saw and lived started to come out in words, soon after his secret marriage to my mother. By the time I became aware of him, Shivkumar Joshi was already an established writer in Gujarati, but an odd one, living and writing from Calcutta, from Bengal, on the other side of the country from where most of his readership lived.

That readership was mainly in Gujarat and Bombay but it also spread across Pakistan, East Africa, Britain, America and Canada; wherever there was a sizeable Gujarati community. Despite this, the books never earned much; there was no question of being able to give up the textile business and write full-time. He took himself quite seriously, and he took the art and craft of literature very seriously indeed, but there was no room to indulge in myths of sculpting masterpieces while starving in garrets. Both my parents had to work and earn because there were three families to support: ours, the one from his first marriage and my mother’s brother’s children, who were also in Ahmedabad. It was a hard-won bit of luck that the business allowed him the time to read and think and produce what he considered his real work.

Puppa would point out that Mohta Bhai had done him a huge favour by forcing him to leave for Calcutta. It would have been fairly easy for a spirited young man to establish himself in Ahmedabad as a painter or a man of letters; instead, Shivkumar was obliged to leave a backwater for the centre of the known universe. When my father arrived in Calcutta in the late 1930s, it was the only Indian city that was truly cosmopolitan. It was also the thriving, undisputed cultural capital of what we now call South Asia: Rabindranath Tagore was still alive, the great cultural movement of the Bengal Renaissance was yet to become supernova; without trying too hard, Shivkumar found himself thrown into a crowded melee of artists, writers, playwrights and musicians, not to mention ongoing political upheavals. Joining his uncle in the family business was unavoidable torture – it felt then like the end of his life – but the move to Calcutta was actually the making of him.

In our house, writing was never seen as an isolated activity. Yes, literature was privileged, as was Gujarati (not unimportantly also the language my mother taught in her college), but on our little first-floor island we were surrounded by the huge ocean of Bengali clashing with the seas of three Hindis and four or five kinds of English; we lived in a neighbourhood that had a reasonable scattering of eccentric painters and graphic designers; acting in plays and directing them was a central pleasure of life, as was photography; the best cinema being produced in India lurked all around, just out of frame. Ours was a fairly small apartment but with very few of the knick-knacks and souvenirs you often found in middle-class houses: most of the shelf-space was devoted to books, piles of Encounter and Plays & Players, translations of Sartre, Ionesco, Lorca and Mishima, and many art books full of reproductions to satiate the unfulfilled chitaaro in my father.

The writer in Shivkumar eventually allowed the chitaaro to go to Europe and America to see his favourite paintings in the original. In 1969, my father was invited to a PEN theatre conference in Budapest and so, at the age of fifty-five, he finally went abroad. Using the paid-for Hungarian leg as a booster, Puppa organized a round-the-world journey that would take him via Beirut to Europe, and through the United States to Japan before depositing him back with us after four long months.

The trip meant that yet another Puppa emerged before my eyes, adding to the three or four already there. Normally, the few Western clothes my father possessed would come out of mothballs only when we were headed for the coldest of hill stations. Now the trousers, shirts and sweater acquired a suit as well (though no tie, it was a Nehru jacket), as he planned how to tackle the different latitudes. I remember being very uncomfortable seeing him try out that Western costume before departure.

I realize now that it had taken me some effort to get used to the stares, sniggers and unspoken taunts of my peers whenever my dhoti-kurta’ed father appeared in school or playground; their inaudible question hanging – ‘Why is your pop in that funny village get-up? Can’t he afford proper clothes?’ Once I’d accepted and internalized his look, the defiant attire he presented to the world, it was hard for me to see him in any other clothes. Now, he became somehow ordinary, diminished, reduced to the level of all those other fathers, suddenly a middle-aged Indian man, the Indianness of his body starkly revealed, the paunch under control but now visible where it had been hidden by the flow of the kurta; the height suddenly short, only five feet six inches as opposed to all of nearly five feet seven; the shirt not sitting right, the collar bringing out his jowls, whereas the round neck of the kurtas normally mitigated them; the trousers all wrong – slightly flared at my insistence but still ultra square – and his legs, which didn’t know quite how to stand in them, looking even odder ending in shoes.

Watching him try out the suit, I found myself worrying about him – it was as if the warrior had divested himself of his armour. It was as if the world was going to claim him and take him away from me. My discomfort came out in bad jokes.

‘Ha, ha, Puppa, you look like a villyunn, you look like Pran!’ I said, naming the dapper alpha baddie of Hindi cinema. But, just as he was unconcerned about people’s reactions to his normal dhoti-kurta, he remained completely untouched by my jeering, even hamming up the villain as he checked himself out in the mirror. My father was a man who could laugh at himself – not a quality commonly found in middle-class Indian Heads of Families at the time. Also, at core, he was a theatre man, an actor, and he had the confidence of the genuine performer – ‘life makes you go through many roles and you have to act them with style!’

Shivkumar with Ruchir, 1971

Around the time I was eleven or twelve, my relationship with my mother was hit by a meteorite. Looking back, it was actually more like a twin-strike, her menopause probably peaking at the same time my teenage hormones decided to kick down the door. There was nothing Mummi and I could say without setting each other off; everything I did was wrong, everything she did was stupid, and vice versa.

I realize now that this was the one thing that knocked my father’s self-assurance: he could handle the worlds he had chosen to enter but he could not tough it out when faced with a schism at the heart of his universe. He watched with growing alarm as my mother and I began to repel each other like two large, ill-matched magnets; the model they had tried to construct, the nuclear family living far away from the imprisoning maze of the joint-family, the three of us united and free from the constant, multi-level attrition of traditional kinship, was coming apart. As my mother chose to put it, many of the things I did felt like a slap in her face.

On the other hand, on a parallel track, Puppa began to communicate with me in a way he had not done before.

When I was around the age of nine or so, someone had presented me with a box of poster colours (gouache, as I learned to call them much later) and I’d begun to mess around. Rapidly, this brush-and-colour stuff became addictive. I’d come back from school and get in some painting before going down to play; I’d wake up in the morning and paint instead of fooling around or doing last-minute homework; my punishments in school began to come because I was caught doodling in class rather than throwing paper arrows or chatting; my choice of presents began to move from toys to art materials.

Puppa talked to a proper painter friend in our neighbourhood who gave him the best advice imaginable – just let the kid paint, don’t interfere, buy him all the colours and paper he wants and then let him be. Puppa was very attentive but also very hands-off: he never told me what to paint or how to paint, he never picked up a brush to show me how, he never stopped me from making mistakes; all he would occasionally do is bring into play Picasso’s great axiom: ‘Every painter needs someone to stand behind him and knock him out when he has done enough.’

Mummi was as proud of my painting as she was of Puppa’s writing. In the creativity of ‘her creation’ – me – she saw a fulfilment of all the hopes of her marriage. She didn’t mind if I pursued art as long as it wasn’t my main profession, just as, later, she didn’t mind that I got obsessed with films as long as I didn’t shove everything else aside to jump into film-making (which, or course, I did). She wanted me to make money, sure, but it wasn’t even about that; there were a few respectable professions – economist, professor of literature, architect, writer – that she would have chosen any time over me being a businessman-millionaire, say. But it was the edgy, rootless, riskily bohemian ways of life she hated. As I got deeper into the spin of adolescence, somewhere Mummi sensed that this ‘creativity’ of mine would mean going against the straight and narrow, not just in education or profession but also in my personal life, and it was a prospect that scared a woman otherwise not easily frightened.

Around this time was also the closest I saw my father come to being frightened himself. At thirteen, I made a choice to go to a boarding school in Rajasthan, right across the country. It was hard for mummi-puppa to afford but somehow they managed – the alternative was the constant trouble in my day school with the attendant fear of expulsion. When I started coming home for vacations, Puppa invented the ritual of the morning drive, where he and I would take the car and go sit by the big lake not far from our house. One reason for these morning trips was for him to start teaching me how to drive, but they also became his hour to talk to me, to negotiate various truces between me and my mother, to try and understand whatever was going on in my hormone-hounded head.

One time I came back for holidays from my boarding school and Puppa and I went for our drive. Sitting by the lakes near our flat, I decided to get it off my chest.

‘Puppa, I have to tell you something.’

‘Yes?’

‘Me and my friend Sudeep went to a restaurant before catching the train.’

‘Yes. So?’

‘Well, Sudeep ordered a mutton burger and I tried it.’

‘Did you…like eating it?’

‘Yes, so I ordered a whole one for myself. And one for Sudeep because I’d eaten half of his.’

Puppa ducked his head, almost smacking the steering wheel.

Then he composed himself.

‘Well…it doesn’t come as a surprise. If we send you out into the world this is a risk we take.’

‘Yeah, I guess…’

‘But. Please don’t tell your mother. On no account must she find out.’

‘Why, what will happen?’

‘One of you will have to leave the house. It’s as simple as that. Since you’re still a child, she will go. And I can’t have that.’

The problem was, Mummi’s adherence to strictures wasn’t just confined to food. There were models of purity, notions of cleanliness, certain ideas of god and morality, all forming a grid inside her and therefore directly applicable to me as well. As she got older, this grid became more inflexible. Luckily for me, Puppa understood that things couldn’t stay so clean, that tangling with art was an inherently messy, prickly, anti-bourgeois, anti-Brahmanical business. He knew it meant immersion in reality, no matter how unpalatable, he knew it meant dirtying yourself with commitment so that you didn’t soil yourself with compromise. It meant breaking sacred eggs and tasting strange omelettes. It meant risking the wrath of the gods.

Our drive-chats began when I was fourteen and Puppa was approaching fifty-eight. It still baffles me how he managed, at that age, to take on all the concerns of a difficult teenager. While my mother tried to deny its existence, my father understood sexual desire. He was an open, sensual man, but my guess is he never managed to live a full and happy sexual life. He had been at odds with his first marriage and young with it; in his second one it was his wife who was at an angle with the whole business; for all her huge tactile sense, my mother always had a hard time connecting love, of which she was a great champion, with lust, around which she was forever a vigilante. My father was never capable of being unfaithful and the different hands that life dealt him meant he had to sublimate his natural instincts into his writing. He wrote freely about sex – too freely, in my mother’s opinion – but he knew acutely what it meant to people, to others, and most importantly to me as I navigated my teens.

Puppa also understood rebelliousness. Both he and my mother had been rebels, they had both bucked the system at various points, first as young volunteers in the independence movement and then again with their marriage. In the conservative Gujarati society of Calcutta, mostly driven by business, our family radiated subversion. But where my mother’s feistiness didn’t cross over to support mine, my father’s did. While she worried about what would happen to a kid who fought the powers, especially in ways she didn’t agree with or understand, my father acknowledged that they had brought me up to question things, which inevitably meant also questioning the rules and principles they, mummi-puppa, had laid down; he had enough of a memory of his own growing up and a supple enough imagination to realize that he wouldn’t always understand why I did what I was doing.

May and June 1975 found us all travelling around Europe and the United States. Puppa and I got to Paris a few days earlier than Mummi. As he watched, I took in all the imagery the city had to throw at a fifteen-year-old. We visited the Louvre, spending a lot of time in the Impressionist wing, and we paid our respects to Picasso and Matisse. Just like Puppa six years earlier, I was happy to see the originals of all my favourite paintings at long last. But when it came to buying reproductions on our limited budget my eyes immediately reached for some posters of soft-focus nudes, sub-Degasian nymphets photographed by David Hamilton. My father gently pushed me into buying one or two of the smaller postcards, it remaining clear that Madame Joshi, when she arrived, was not to have her sensibility assaulted by these ‘art’ photographs.

There was, however, no avoiding the newspaper that was waiting to assault us all in an Indian restaurant in New York. indira gandhi declares emergency! said the main headline. freedom of speech suspended cried the subheader.

By the time we returned to India, the crackdown was in full force – arrests, censorship, the infamous ‘20-point Programme’, slogans of loyalty on the walls and billboards, all of it. I got it that things weren’t good, but I returned to my boarding school still excited by my new T-shirts and all the small soft-porn pictures and books I’d picked up behind my mother’s back. It was only when I came back for the Christmas holidays that I really began to understand what was happening: most political opponents of Indira Gandhi’s regime were in jail, civil liberties were gone, the right to criticize the government in print was indefinitely suspended, the poor were being rounded up and relocated from their slums, working-class men were being rounded up and sterilized, the country was – no mistaking it – under a dictatorship.

My father showed no sensible fear or caution. Probably the one thing that kept him out of jail was that he wasn’t affiliated with any political party, having had no time for any of them after 1947. Once he had assessed what was happening, he began writing against Indira and her son, publishing his columns every week in a big Gujarati daily in Bombay. The only nod to strategy was that he called Indira and her son by the names of mythological demons, a reference so thinly veiled it was almost more insulting. After a while, the editor in Bombay was pressured into stopping the columns. All that did was make my father all the more determined.

The Emergency lasted for a little more than a year and a half. On my visits back home, I could see the fight-light in my father’s eyes. It was a quiet change of energy, but it was palpable all the same: the warrior was back at war. He was deeply angry about what was happening to his country, but in terms of his personal situation he couldn’t have been more acutely focussed. It was as if he’d cleared his emotional desk to make himself ready for battle. He had always talked to me about important things, but now, on our morning drives, he made an extra effort to be very clear about why he believed what he did, why he was doing what he was doing. It was perhaps a function of my age that I was worried but mainly proud, whereas it may also have been to do with her age that my mother was proud but mainly worried.

When the Emergency was at its peak, my father attended a meeting PEN had called in Calcutta. The idea was for writers and journalists to meet and have a dialogue with Yashpal Kapoor, then Mrs Gandhi’s chief public relations henchman. While most other writers fudged and shuffled, Shivkumar Joshi stood up and let the Safari-Suit know in no uncertain terms what he thought of the Emergency and the suspension of free speech. It was after this evening that my mother’s anxiety really mounted. Nothing happened though, no knock came on the door, no summons, no jail. Puppa’s reading was that the situation was already getting out of hand for Mrs G and her cohorts. He was right.

When the end came, it was quick. I finished with school just before a confident Indira declared national elections. For the duration of the elections, people were again allowed to write what they wanted. Many had lost the habit of free speech but many more, including my father, had not. People spoke out, people campaigned, people wrote passionately and incisively. Indira Gandhi and her Congress were swept away in a landslide. I shared my parents’ elation and I felt as if it was my own triumph as much as anyone else’s.

On our morning drives, Puppa and I went back to discussing art.

Unlike me, my father didn’t drink, didn’t smoke and never ate meat. He had survived jumping across Ahmedabad rooftops, running from the police, he had survived the Sardar’s sword, and he had survived the Emergency. I imagined he would last forever but, typically, it was my grandfather, Mohta Bhai, who did that, outliving several of his children and one or two grandchildren before dying at the age of one hundred and one. My father died two years before Dadaji, going far too early at the age of seventy-one.

Sometimes I find myself doing strange time calculations when looking back, as if working stuff out mathematically will yield something I’ve missed.

In the matrix of marriage and childbearing from which my parents emerged, my mother should have been an older aunt to a child born in early 1960 and my father a young grand-uncle. They themselves were both born in the heavy penumbra of the nineteenth century – which always seems to have left India later than many other places – and yet they both ended up dealing with a twenty-something son who hammered their ears with Iggy Pop, Talking Heads and Pere Ubu. In the last few years we had together, my father saw me struggle with drawings, photographs and film that had far more to do with people such as Joseph Beuys, Robert Rauschenberg and Jean-Luc Godard than they did with his favourite Cartier-Bresson and Matisse.

In the aggregate of time, there is a massive ‘only’ attached to the seventy-one years he lived and this gets magnified when I do further sums and come to the result that we were close only for fifteen or so of the twenty-eight years I had with him; of those, I was away and out of his life for about seven, and living my own adult life while co-habiting with my parents for the last six.

Trying to flip to his point of view, I entered his life when he had already lived two-thirds of it, though he was not to know that then. He had many friends, but he had a closeness with me that he had with very few of his contemporaries, and in some ways I know that I was the one closest to him. It may have surprised him, the friendship he forged with this unexpected late child; he was used to the idea of unconditional love, of missing it, of fighting for a space where it could exist, of seeing it mutate and evaporate. I think what might have really surprised him was being able to express that love and find it reciprocated from this strange, usually adversarial quarter.

Not everybody I know has had difficult or disastrous fathers, but far too many of them did or do. A very few of my friends have brilliant, nourishing relationships with them, but most of them don’t – there was often this odd look I’d get when speaking warmly of my old man, as if I’d ordered steak in a vegan restaurant. Now that he’s gone this has lessened to some degree, praise for the departed being harder to censure.

It’s difficult to explain the huge span of time my father covered. Again, it’s not about the figures. It’s not about the hardware either, though this man born under gas-lamps enjoyed his technology – one of my big regrets is that he missed home computers and the Web by only a few years. The span of time Puppa gave me has to do with him being able to share with me his whole store of memory, with keeping it sharp and yet supple and on the whole free of bitterness, with being able to analyze his experience with an open heart. This ‘time’ I received from him also has to do with him being receptive to a future he could not know. He knew the external world would soon change beyond all recognition and that he would probably not live to see many of the changes. It was with the internal world he realized he could most help me, by giving me the deepest, most genuine sanskaars I would need to handle what was coming.

I remember thinking when he died that he’d somehow managed to stay genuinely young, for himself and for me. I remember this again and again as I watch others’ parents get old and as I watch my own friends starting to become set in their ways and their thinking. In the devastation of his going, I remember feeling inexpressible gratitude. In the middle of that pain, I also remember feeling sharp relief that I myself, at least, would never have to face the challenge of being a father.

Featured photograph by myodie; in-text photographs courtesy of the author