Hourglass. Calcutta is an hourglass and each person is a grain of sand. Each day, we all pour through the opening. Every morning, each of us begins to slide downwards. By night all of us have squeezed through to pile up below. The trajectory of the day is different for each of all 15 million of us, but at the end point we find ourselves in extremely close proximity to everyone else. Of course, some of us don’t make it to the other side. Every day several thousand grains just disintegrate in the crush and disappear, while many other thousands leak out, escaping the gravitational hug of the city to travel in different directions. As for the rest of us, we stay piled up on each other through the night, waiting for the morning to nudge us again and send us on our way.

It makes no sense at all, of course. The 15 million figure is for the sprawl of the Kolkata Metropolitan Area, aka Greater Calcutta, while the strictly defined area of the city is home to just four and a half million people. On a normal working day roughly another four million individuals commute into the hourglass and pour back out into the hinterland in the evening.

But, still, could it be that every individual’s day in the city has a fulcrum? A narrowest point? And at what moment do you feel you’ve made it through to the other side?

Thinking of fulcrums brings me to thinking of weight. Between the hours of 6 a.m. and 11 p.m., the weight of human beings pressing down upon the area of the city proper doubles. Between evening and dawn the pressure disperses. The hourglass flips over, but remains in the same place. Why doesn’t the ground give way under this repeated onslaught? Or does it?

Tremulously perched just north of one of the biggest deltas in the world, despite its 300-year-long pretensions to solidity and stability, Calcutta has a constant sense of something shifting underfoot. The ground underneath, according to some geological definitions, should not be called ground at all, made up as it is of layers of silt deposited over millennia by the River Ganga. Think of monumental blankets of mud entangled with each other, their shifting thicknesses embedded with massive pockets of water. Or imagine that below the top layer of earth the whole city is actually supported by an immense water table interrupted by sodden partitions of soil and rock. Then think of the buildings coming up and wells being sunk to pull out water. Imagine thousands of such buildings pulling up the water from underneath themselves, gallons and gallons of it every day, and then think of the man sitting on a high branch sawing the wood at a point between himself and the tree trunk.

Layers below, tectonic, horizontal. The vertical man-made things rising out of this earth also layered, as though they’ve sucked up the shifting and scraping below through roots of brick, cement and iron.

There are times of the day when it feels as though this – one of the most densely populated cities on the planet – is made up entirely of traces and residues, shredded palimpsests, ghosts of scaffolding all stacked on each other. A town of cards, a frontage-ville, a junkyard of abandoned movie sets where no picture can ever be finished, where even the screens and box offices are fading, painted backdrops.

Think of a constant background of thick tropical vegetation in front of which history plays mischievous optometrist, inserting and removing walls and buildings as though they were lenses.

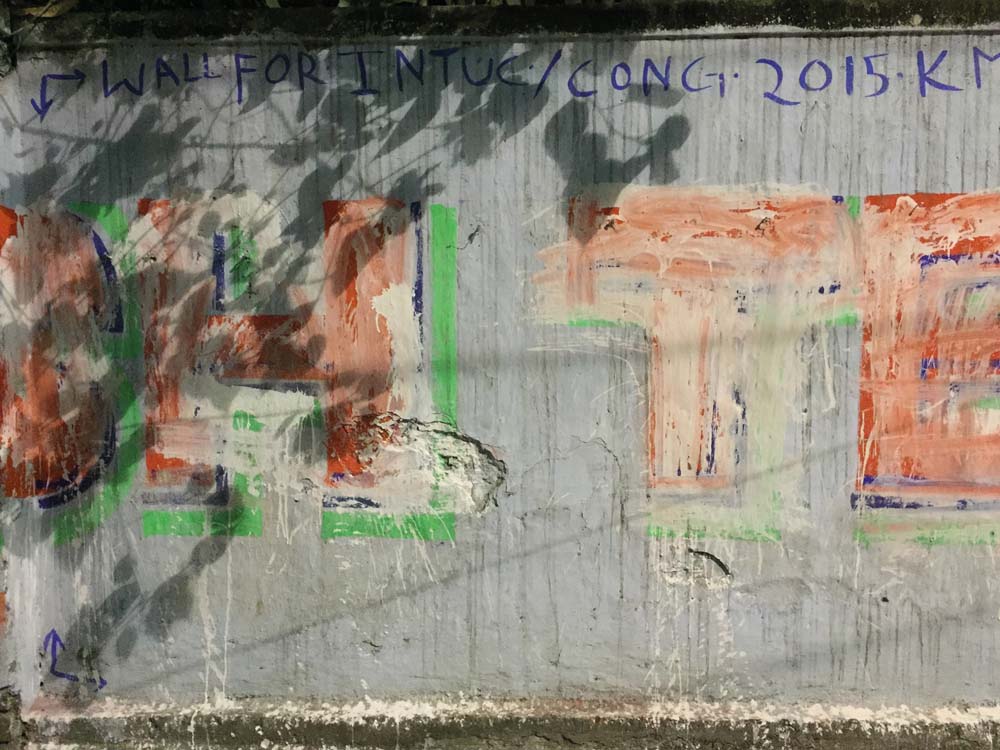

Walking past walls in this city, I’m often reminded of one of my favourite painters, the American Jasper Johns, and his work from the 1950s and 60s. Most people here have never heard of Johns, and yet, somehow, everyone seems to have internalised his famous precept: Take something and do something to it. Then do something else to it.

Someone once told me: ‘Calcutta is the bastard child of geography and colonial greed, and it has seen off every kind of capitalism there has been.’ The opposite could also prove as true: new forms of capitalism will see off every kind of Calcutta there has ever been.

Sometimes it feels as though Calcutta has also seen off every kind of history there is. ‘If you truly want to see the end of history, come and visit Calcutta.’ But we know this can’t be so – it’s history that always does the seeing off.

Perhaps the weight of history is the collective weight of every person who has lived and died in this city over three centuries. A lot of history has been buried here, but, equally, a lot of it has been cremated daily.

This is a settlement fundamentally sculpted by water: floods, tides, indefatigable damp, river and rain – more kinds of rain than there are shades of green in the jungle. But woven through the genealogy of water, there’s also one of fire, a long history of cooking fires on the street, small winter fires, blazes, conflagrations, riot bonfires and strategically executed arson.

Unlike in other towns, here the fire hazards are blind to class; you can find tinderboxes distributed everywhere: in slums and the old commercial buildings abutting the stock exchange, in nineteenth-century port warehouses and modern hospitals, in Edwardian piles and apartment towers with brand-new cladding.

We know better than most places how, whether through oil, electricity or perverse human agency, fire can piggyback on water.

The flyover came up about twenty-five years ago. It wasn’t right next to the apartment where I live, but there was only one row of buildings between it and me. A gap between buildings allowed me to see a sliver of it, the traffic noise funnelling through to my fourth-floor window. The honking from the big avenue below was now amplified by the overhang – a whole new road had been added on top of an already overcrowded one.

Now, the first night sounds come after 11 p.m., when the supply trucks are released from the municipal borders and allowed to enter the city. The road below the flyover is a major artery and the truck horns doppler past my balcony till the early hours of the morning. The flyover is one of the few clear stretches of road in the city without bumps or traffic lights, making it great for drag racing. At some point after midnight the rich boys start with their fancy, heavy motorbikes, hammering by in ones and twos, east to west, west to east, till it’s time to pay off the traffic cops and go home. There is an interval, a feint of silence, before the street dogs launch into their nightly opera, the glissandos of howling and percussive barks bouncing off the buildings. After the dogs comes the sound of small hooves drumming on the asphalt, a march of goats, interrupted by stick taps and clicking sounds from the mouths of the men herding them to the meat shops. A small truck passes by, the open back packed with labourers heading somewhere. Inching towards dawn, someone in the next building switches on the water pump to fill their tanks. The pipe outside my bedroom window starts to shake and clank; I know it’s neither burglar nor water, just the two mongoose-like creatures heading down from their nightly hunt to go hide in the small clump of trees at the juncture of three building compounds. A faint prickle of noise turns from mechanical to melodic – the first azan from the mosques a mile away. As the dawn begins to firm up, there is birdsong from the trees. By 7 a.m. all other sounds are hammered down under the rumble and scream of the day’s traffic.

Growth climbs onto growth. A tropical forest is made up of many competing things; there’s a continuous argument between different kinds of vegetation about what belongs and what doesn’t. A city built on a swamp can easily take on the characteristics of what it has tried to tamp down.

People often speak of time as a running river. Here time becomes a swamp, the days and weeks bubbling and turning in solipsistic swirls. It often feels as though the city has no present and no future, as if the only thing growing here is the past, the misremembered twining around the half-remembered in an ever-thickening jungle of memories.

Every day the city seems to sink a bit under the load of this ever-present past. But then you realise: it’s not that the city has no present or future, it’s just that the present and likely futures are different from those available to other cities. It’s just that history does its sums differently here and comes up with strange answers.

At certain points history strikes a match and situations are gutted by fire. At other times structures collapse under the weight of their contradictions.

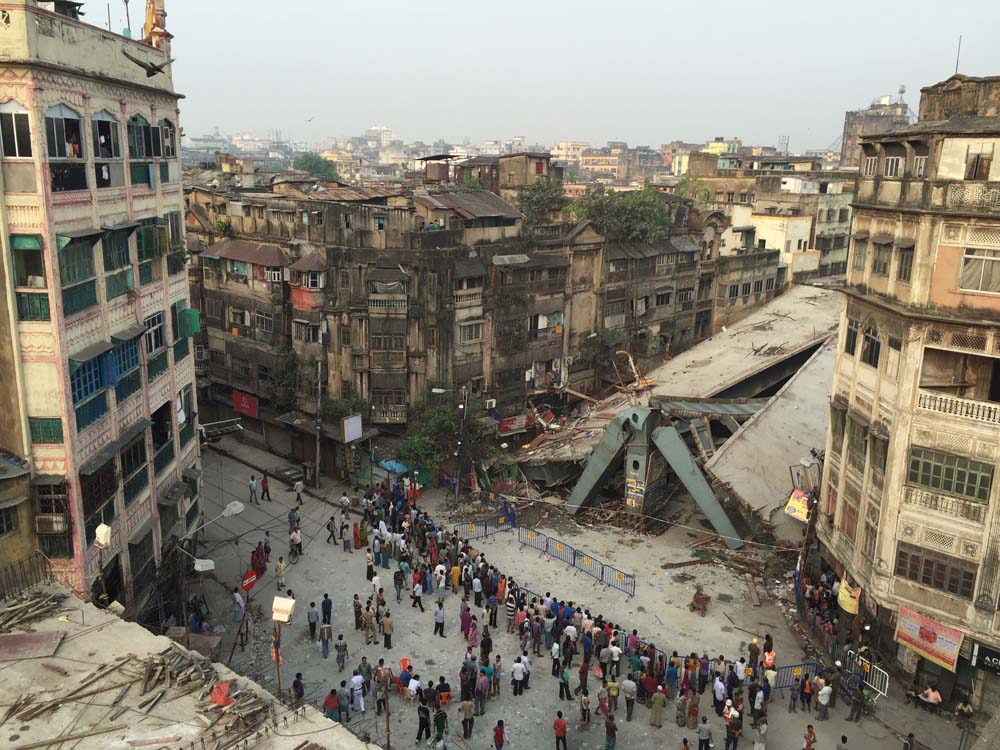

March, 2016. In north Calcutta a section of a flyover under construction came crashing down at midday. Several people died. I went there two days after the event with my friend SC who is a press photographer. The immediate clearing up had finished, the easily reachable bodies taken away, the injured shifted to hospital. Right at the crossing of two roads, the fallen slabs made a kind of high awning, under which different emergency crews and salvage workers were carefully shifting the debris while sniffer dogs nosed around for bodies under the rubble.

SC and I decided to get to a rooftop. The building we went into was built in the early twentieth century as a sort of middle-class tenement for traders from western India. The entrance led to a courtyard lit by a stained-glass skylight five floors above. The blue light falling on the chessboard of the marble floor briefly pulled us into a different world. We took the wooden stairway and came out onto the terrace that overlooked the collapsed slabs. The area has some of the oldest surviving buildings in the city, many of them sealed off for being hazardous but impossible to demolish because of protracted property disputes. Around us we could see the maze of tilted, almost toppling brick and woodwork and ramshackle masonry that visiting photographers love to shoot as typical of Calcutta.

Leading away eastward from the crossing was the completed portion of this flyover which was supposed to connect the airport and the railway station at two different ends of the city. From here it looked as though a dirty grey river of concrete had rammed its way through the architecture, the asphalt flooding everything up to the second floor of the roadside buildings. At places the edge of the roadway was literally inches from the windows and balconies of the old houses. I knew of nowhere else in the world where someone would conceive of such public engineering, much less actually try and execute its construction.

The ‘accident’ below us was also part of this kind of engineering, resulting from a cat’s cradle of corruption that criss-crosses from the current state government to the previous regime to the construction companies and the Public Works Department officials charged with overseeing them. From above, the broken structure managed to pull off a strange trick: on the one hand it looked as if it had been dropped the previous night by aliens, and yet – this being Calcutta – it also looked perfectly woven into the surroundings, as though it had been there, in exactly this state, for decades.

‘Nothing new can ever be added to this city. It has to be already old, flawed or damaged for the city to accept it.’ I can’t recall who said this to me, but I remember thinking about it while looking down at the crashed concrete.

Sometime during the 1960s, photographing Calcutta became an international safari sport. Western photographers began to visit, either directly or stopping by on their way to or back from Vietnam (Look! Human devastation can happen even without the help of napalm!), shot rolls and rolls of film and carried back their emulsion trophies to print on the pages of magazines or hang on their walls.

Rapidly a currency developed of Calcutta pictures, an immediately decipherable image vernacular to compete with famines in Africa and exotic rituals from Bali. The ‘icons’ from Calcutta that became established were ‘starving child’, ‘begging mother and child’, ‘rickshaw puller in the rain’, ‘protest procession by communists’, ‘the heroic nun ministering to the dying’. This was leavened by ‘positive’ images of the Durga Puja, when the Mother Goddess is celebrated and the clay statues slide into the grey-green river.

The old titles have been removed now, taken away from us. Cities in other countries are far more terrifyingly disastrous; Calcutta now has fewer people than Delhi or Bombay, though we’re still the most tightly packed. The one thing that still adheres to the city is the husk, the simulacrum, of a once-great culture. And yes, despite not having any industry like Bombay or anywhere near the number of motor vehicles Delhi has, we are still the ones with the worst air, water and sound pollution among major Indian cities.

Sign in to Granta.com.