A Little Story about God

Here’s a story that just came to mind. Perhaps I could make use of it sometime. Perhaps not. Probably not. When you hear the story, you’ll understand why. I think of stories all the time, the reason I don’t write them down is that they’re all as strange as this one.

The story is about a family who travel in a car through the Yugoslavian countryside. It could be Yugoslavia towards Trieste in the direction of Austria, or it could be a country road in the south of Ávila: in my memory, both regions look pretty similar. The family suddenly notices, either side of the highway, in fields green and sprinkled with trees, a large quantity of rabbits. That is to say, all of a sudden they realise that the landscape has become totally overrun by rabbits. They continue down the road, and, as they do, the rabbits get steadily bigger and bigger. The rabbits are gentle and timid – in fact, they behave as rabbits normally do – but nonetheless their size is troubling. At this point, someone in the car makes a comment that is, really, the key to the story: that the rabbits are getting incrementally bigger, and that the bigger the rabbits become the fewer rabbits there are.

This is, of course, logical. A few kilometres further and there are no longer thousands of rabbits as before, but hundreds, and later, just a few dozen. At this point, they are already as large as cows. A little further and the rabbits are as big as elephants. In an area where before there were, let’s say, a hundred rabbits, now there are only two or three. The end of the story is inevitable: the road trails off leading into a wide grassy valley, at the bottom of which appears a single gigantic rabbit whose erect ears rise to the clouds.

I’ll never write this story, that much is clear. I’m not really sure what it means. Maybe it has something to do with St Thomas Aquinas and his proofs of God’s existence. Given the existence of small rabbits, there must previously have been bigger rabbits. In reality, the car does not go down the road, but rather goes back in time like the arrow of entropy. The story, in fact, tells of the origin of all things and of God, and supposes that if God or a transcendent explanation for these things do exist, then they must be terrifying.

*

The Oucro

Today marks ten years since the departure of the Oucro, who lived with our family for some twenty months when I was a child. Ten years have passed, but I recall everything that happened with such clarity. All of us had become fond of the Oucro, though none of us really understood him. Not because he didn’t speak our language, but because the things that he said didn’t seem to relate to our lives or reality as we knew it. Only Armida, cousin Constanza’s daughter, understood the Oucro. Perhaps because of this when the Oucro decided to abandon us, he took her with him. He left another child in her place, very similar to Armida, just as sweet, just as intelligent, but everyone in the house knew at once that it wasn’t Armida, and that the real Armida had gone with the Oucro. Of course, we didn’t tell visitors anything. Even her grandparents, who live in Córdoba, and those who we see a few days a year, all of them still believe that the current Armida is the same as always. Only close family and intimate friends noticed the change. I think it’s a shame deceiving such lovely grandparents, but what else can we do? The truth would upset them.

The Oucro was the colour of rubber, and huge. He lived in Manú’s old room (Manú had run off to Brazil chasing a married woman) but since he didn’t fit in the room, he’d extended out of the window and into the garden up to the pool, where he’d buried his head, not because he wanted to drink the water, nor to cool down, but because, he said, he preferred to look at things through water. In his world, young Armida explained to us, there was no air, or rather the air had some of the consistency and density of water, and for that reason the Oucro didn’t understand how we lived as we did, with so sustaining us, falling over and hurting ourselves all the time and having to put stairs and railings everywhere, since the air was so thin that it didn’t give us support of any kind. We told Armida that the air the Oucro was describing better resembled a kind of fluid. His opinions, on how insubstantial and dangerous terrestrial air was, seemed similar to those of a fish, something used to living in a dense and viscous medium that allowed one to rise just as one could descend, and in which there was no falling, no law of gravity. But the Oucro was in no way a fish and he became annoyed when we compared him with a fish and when we speculated that his world must simply be covered with water.

He certainly did not look like a fish and he didn’t possess any of the characteristics of fishes, like eyes without eyelids, fins, scales or gills. He more closely resembled a giant tree root. Occasional visitors to the house took him for precisely that, a root, or perhaps the trunk of a crazy tree that grew from the window, arched over the garden, advanced over the grass and sank at last into the pool. They couldn’t figure out where the treetop was if it were a trunk, or where the trunk was if it were a root, or where the leaves were if it were a branch, or where the root was if it were a tree.

We let them look in puzzlement at the Oucro. Sometimes we said it was a ficus or even a deformed kapok or baobab tree, brought from Africa by Uncle Manú. They didn’t understand why we didn’t cut it down and sell it for wood. They touched it and the Oucro would quickly stiffen, giving the impression of a consistency woody and vegetal.

I remember the first time that the Oucro spoke. He had only been at the house three or four days, and none of us had imagined that he could talk.

‘There are tremors,’ he said, in a very slow, deep voice. ‘There are emotions. Forgive me, banished star. I am like a flower amid primates. I like crimson, but blue disappoints me.’

We all went out into the garden to listen to the Oucro speak. It was a summer night and the sky was full of pulsing stars. Rosa, Consuelo and Constanza, the three cousins, and the husband of Constanza, Guido, and Romulo my father, and Evandra my mother, the writer of this text, and Armida and her two sisters, Louisa and Maria Regina – everyone went to the garden. At first we didn’t know where the voice was coming from. When we realised that it was the Oucro, we were delighted.

‘The Oucro says that he feels lonely,’ said young Armida, quite naturally.

‘How do you know?’ asked her mother.

‘I know,’ said the girl.

Forgive me, banished star, forgive me, faint stardust, forgive me,’ said the Oucro. ‘I am not a swordsman, yet nor am I a monk.’

‘He says that he’s hungry,’ said the girl. ‘He wants to eat something.’

‘What does he eat?’ asked Cousin Rosa in a nervous voice.

‘He eats virgins,’ said young Armida. Rosa and Consuelo both screamed. Luisa and Maria Regina didn’t know what a virgin was so they stayed quiet. They thought that a virgin was a wooden or clay image of the Virgin Mary, or maybe an imprint of the mother of Jesus or of the Holy Family. Armida didn’t know what a virgin was either, and so with all her innocence, she asked.

‘A virgin is a woman who isn’t married,’ said her mother. ‘Was that really what the Oucro asked?’

‘No,’ said young Armida. ‘He said that he feeds on suffering and penances.’

‘On suffering and penances?’ asked my father, undoubtedly thinking that he had misheard. He had inherited premature deafness from his grandfather and from his great-grandfather. It hasn’t manifested in me yet, probably because I’m still young.

Indeed, the Oucro fed on human suffering and on all things that torment us: unhappy thoughts, envy, fear, remorse. It was enough to approach the Oucro and be at his side for ten minutes to feel like all your problems had disappeared as if by magic. It was akin to how plants feed on the gases that poison us, or on all those substances that are, for us, detritus or dung. As I said, the Oucro had something of the plant about him.

‘The Oucro says that he doesn’t understand why we are always moving around,’ said young Armida. ‘He wants to know why we don’t just settle in one place like he does.’

‘People can’t just remain still in one place,’ we explained. ‘If a person stays still in one place, he’ll die.’

The Oucro disagreed.

‘You just need to find the right place,’ said the Oucro, through the lips of young Armida. ‘I understand what you seek. Granted, the place might be far away. But once you’ve found a suitable place, why would you move? This house in which you live looks to me like a very suitable place. Why do you come and go endlessly?’

The Oucro thought like a tree, or like a rock. He thought like a flower.

We asked him things about his world. We asked him how long Oucros lived and he didn’t understand the question. He told us that Oucros are always alive.

‘Ah,’ we said to him, ‘so you’re immortal.’

‘No, no, we also die, like your trees. But another is born.’

‘But if another is born, then another is born,’ we said to him. ‘The one that died, died forever. The new tree is a different tree, not the same tree as before.’

‘You’re wrong,’ said the Oucro. ‘All trees are the same tree. When one dies in one place, another is born in another place. All are the same and all have the same memories. With us it’s likewise.’

It was a real shame that the Oucro ended up leaving. He told us he was very fond of us, and that between us we kept him very well-nourished, but that eventually he would have to return to his home. He never told us where that home was, although we all assumed that the Oucro came from the stars. We enjoyed his company too, because since his arrival we’d felt permanently content, passing the day laughing and embracing one another.

Normally, we tried not to show how happy we were so as not to attract the attention of neighbours, who were envious people. We didn’t get sick either, when someone caught a cold it was enough to approach the Oucro and stand next to him for about five or six minutes in order to recover. My father caught pneumonia during the flood of the La Plata River, but he cured himself by sleeping under the Oucro. He didn’t try penicillin. Young Armida had asthma before the Oucro’s arrival, but after she started talking with him, the breathlessness and fatigue stopped bothering her. Yes, it was wonderful having the Oucro with us, though the house was starting to crack apart under his huge weight, and he grew so so so much that he burst through the walls of Uncle Manú’s room and began to occupy the laundry, the upstairs hallway and my parents’ bedroom. This forced my father to build an extra bedroom in the garden, attached to the house. All the plants and flowers flourished if they were close to the Oucro. We planted tomatoes under arched branches, and roses – there grew roses so enormous, so richly scented, that it was like something out of a story.

Nobody knew how the Oucro arrived, nor did they know how he left. One morning we woke up to find he wasn’t there. We looked for him in the adjacent gardens and went all the way down to the river, remembering how much he liked the water, but we found not so much as a trace of him.

*

The Beginning of the World

If we go back to the beginning of the world, we shall see, for example, how the streets withdraw and the towns disappear, trees grow and the countryside returns. We see large buildings cleared from the cities, buses change into trams, trams to horse-drawn omnibuses and then landau carriages. If we go back to the beginning of the world we see a nurse in the room of a hotel; we see two children, eleven and twelve, abandoned on a beach in North Africa; we see a pleasure yacht sunk between two islets in the gulf of Mexico; we see a white-haired man who has lost his mind trying to catch a squirrel in a park in England. All these things have consequences and are the product of causes, and those causes lead us back into the past, which recedes endlessly, and we watch as civilisations disappear, how rifles convert into muskets and muskets to crossbows and crossbows to swords and swords into maces. Yet, where is the beginning of the world?

The world begins like this. It begins one cloudy morning at a riverbank in Africa. There, beneath a tree, at the muddy bank of the river, is a monkey with greyish fur. It isn’t very tall, no taller than a ten-year-old might be today. It doesn’t seem quite human. It’s an animal, but it walks upright on its hindquarters, though its forelegs are rather long. It stands at the bank of the river, trying to see the waters covered by fog. And it is screaming. It screams with all of its strength, with an immense grief. And that scream, that precise scream, is the beginning of everything.

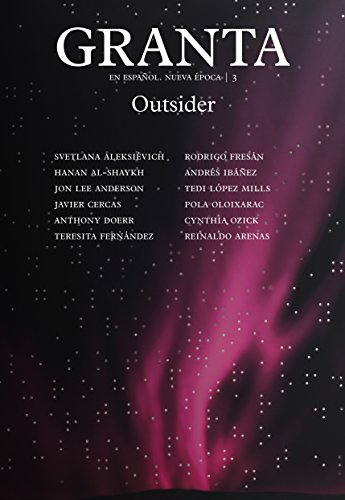

This story was first published in Granta en Español 3: Outsider. Visit granta.com.es for more.

Image © x@ray