Feel what I feel.

Stand with your legs together, toes pointing forward. Open your hips so the backs of your knees are touching. Slide the heel of one foot in front of the other until it meets the toes. This is fifth position.

Under certain conditions (flexibility, training) your two feet will be firmly locked together: heel to toe and toe to heel. Your knees will be straight, your pelvis will sit squarely above your knees. It’s not natural but it is elegant. Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man but pulled together and not human spreading all over the place.

Contained.

Fifth is a position to begin things from. Fifth is a frequent point of return. It’s also itself. Movement. Dance, even if it is still. See what I see.

James is teaching class. He wears a soft T-shirt and a pair of loose sweatpants. The soles of his dance sneakers are split like ballet slippers so he can demonstrate a pointed toe more easily. He’s a little vain about his feet, their high arches.

‘. . . And contain,’ James says, as the dancers close their legs to fifth position. ‘. . . And contain.’

The class – at an Upper West Side New York City studio – is by invitation or introduction only and filled with professionals. I picture the dancers, spaced out along the barres lining three sides of the room. I see the additional freestanding barres in the center, a spot where I might have stood. I’m not there. This is part of a story that was told to me.

James is prowling the studio in his soft clothes, his soft shoes. Not prowling. Gliding. He doesn’t appear to scrutinize the dancers, but they’re aware of his gaze, mild but penetrating.

‘. . . And contain,’ he says.

The dancers think they know what he means by containment. He’s asking them to keep their upper bodies still and placed, to not let the motions of the legs disturb the carriage of the torso. To come firmly to fifth position and not rush through or blur the moment. James means a little more than that. He always means a little more. He raises his hand and says, ‘Thank you, Masha,’ which is Masha’s cue to stop playing the Chopin mazurka she’s been plunking out with heavy-handed precision. Masha lifts her hands from the keyboard and picks up the New York Post.

James walks slowly to one of the center barres, where everyone in the room can see him.

‘Containment,’ says James, ‘is one of the things ballet gives us.’ He takes fifth position on demi-pointe: heels raised, balancing. He’s not demonstrating technical perfection; he is middle-aged and wearing sneakers. He’s demonstrating intention.

James steps out of fifth position, impatient with his body. ‘Music tells us to move, to dance,’ he says. ‘But when we are still within music, we absorb all of its power. We are its container. Not every movement needs to go out into the world. We can keep some for ourselves. Contained. Powerful.’

James smiles.

‘Restraint,’ he says. His voice confers full sensuality to the word. ‘Restraint.’

Such a subtle thing to describe. ‘Other side,’ he says, with a nod to Masha, who rustles her paper down. The dancers turn and place their right hands on the barre. It’s still morning, still barre, but the dancers feel James has said something beautiful, or true, or deep. It’s why they’re here. Even when his words don’t make perfect sense, they create an atmosphere that is pleasurable. It’s nice to be reminded one is an artist, especially on a Monday, with a full week of rehearsals ahead and a weird pain in your hip.

James looks across the studio, scanning the dancers. To teach is to hope.

His gaze falls on Alex, although he doesn’t remember his name. The boy had been brought along by one of James’s regular students and introduced as ‘My friend visiting from Atlanta Ballet.’

James has been observing dancers, teaching dancers, a long time. His assessments are swift. He looks at Alex and thinks, Nice but stiff, maybe a late starter, the body is good but –

James stops. It’s been so long since he’s been surprised.

Imagine what I imagine.

Alex has been listening hard.

‘Contained.’

‘Being still within music.’

‘Restraint.’

Something turns over in Alex’s mind, like a combination lock sliding into its last number.

He raises his heels, shifts his weight to the balls of his feet, recrosses his legs. He lifts his arms. He is still.

James watches.

The music plays. Masha vamps, giving the dancers time to find their balance, ‘find their center,’ as they say.

What Alex finds is that his body has changed. Somehow, James’s words are within him. He understands he is a container. For music, for movement. These are things he can hold and control. It’s a small click of rightness that opens everything. He’s never felt like this without drugs.

This boy, this young man, did, in fact, come to ballet late and his love for it still embarrasses him. The culture, the music, the costumes, none of it is ‘for’ him. He’s a straight man, a mixedrace American kid, a lower middle-class boy. He should be putting his coordination, his strength and flexibility, to use in some other field. Why should he prance around stage in makeup and tights, pretending to be a prince?

In his teens, he justified his obsession by calling it an escape, an opportunity, a place to meet hot girls. He could jump and he could turn. He was a boy; he got scholarships. Now, his career has started and he’s ambitious. He doesn’t understand why he’s also a little depressed. He doesn’t like the way he dances.

He wants it all to mean something. Ballet. His life, maybe.

Now, in James’s class, for the first time, he sees how he might make something. In stillness. With his body, which is not perfect, and his mind, which is a total shit-show. He’s twenty-two.

He’s beautiful. He’s making beauty.

He doesn’t feel like a man or a kid or a boy.

He feels like a god. ‘But not in an asshole way.’ (This is what Alex tells me, when I hear his side of the story. Except for style and point of view, it’s the same as James’s version. If they were unreliable narrators, they were – in this – a perfect pair.)

James watches Alex feel like a god.

Perhaps a bar of light penetrates the speckled grime of a nearby window and goldens Alex’s cheek, his clavicle, a sinew of his raised arm. The features of his face are too harsh for conventional beauty, but everyone looks noble in chiaroscuro.

‘Yes,’ says James, nodding at the young man and raising a finger. ‘That’s exactly what I mean. Beautiful.’

Alex looks at James. Confirmation. He’s not crazy. What he feels is real and someone sees it. James.

James finds himself shaping the class around the young man, testing strengths and probing weaknesses. He watches his words take shape in the boy’s body. It’s one kind of power to understand, and another to bestow understanding. James feels something in his chest and notices that he’s happy. When class ends, he sits on a little chair in the corner for a few minutes, approachable. He accepts gratitude and exchanges gossip. Alex hangs back, wanting a little privacy. Later, he will tell James he was afraid he might embarrass himself, say something stupid. Words aren’t his thing. But when it’s just the two of them and James is looking at him with kindness and interest, he does his best.

‘I learned more in the past ninety minutes than I’ve learned in my whole fucking life,’ Alex says. ‘I’m going to be in New York for the summer. I want to, I mean, is there a way I can study with you? Is there a way, even, I don’t know if you coach privately or, maybe we could, I don’t know.’

What he wants to say is ‘I feel as if I’ve only now been born.’

‘Yes,’ says James, in just the right way. With gravity, with depth. ‘Let’s work together. All right.’

‘I need –’ Alex says, and then stops. He needs a lot. ‘I need someone to –’ He can’t finish the sentence. It’s not that he needs help, although he does need that. But help has been given to him. He’s a man who wants to dance ballet, he’s had no trouble being seen. What he needs is for someone to help him see himself. He needs love. He needs a friend. He needs beauty. He needs someone to talk to him about art. He needs –

‘I understand,’ says James.

This is what I remember.

James is telling me about meeting Alex. We’re in our usual positions at Bank Street, where my father and James live. (I don’t live there, I visit.) Bank Street is what everyone calls the apartment, as if it were the only one on the block. It’s the parlor floor of a four-story brownstone, the apartment purchased in 1975 by my father with money from an inheritance. James sits at the piano in the large front room, and I’m perched nearby, on the rolling library steps that serve the tall bookcases by the windows. The steps don’t roll very well and have been much clawed by the cats.

I don’t live at Bank Street, have never done so, but in my heart, this is my home.

James and I are family and not. Teacher-student, and not.

Confidants, and not.

I could be his daughter, but I’m not.

My father and James have recently started using the word partner for each other. James used to say companion. I’ve never heard either one use boyfriend or lover. They’ve been together for twenty-three years.

I love James very much. I love my father too.

Or: my father, I love, and James I sort of want to be. Maybe I mean: have? I’m twenty-four.

I haven’t met Alex yet. I will soon.

‘I’m not a young person anymore,’ James says. He folds his arms and frowns at the keyboard. ‘At a certain point – and I’ve reached it – you realize your moment has passed. You won’t achieve those dreams of youth. You have to make new dreams. But I don’t have any new dreams.’

He plays a single note on the piano.

‘It’s not about me,’ he says. ‘It’s wanting the things I care about to continue. To give that to someone else. Otherwise, everything I care about dies with me.’

He plays a few chords. The piano needs tuning.

‘That’s not quite true,’ he says. ‘One wants another chance at things.’

I think I understand about wanting another chance at things, and I’m only twenty-four.

‘Oh, Carlisle.’ He almost smiles. ‘You know what’s more terrible than giving up a dream? To discover you haven’t.’

He might be crying. ‘It’s not about this boy,’ he says. ‘You do see that?’

And then –

‘Is it worth it? All this –’ He shuts his eyes. ‘All this wreckage.’

I’m not sure what he means by wreckage. Himself ? His career? His relationship with my father?

Perhaps he only means life.

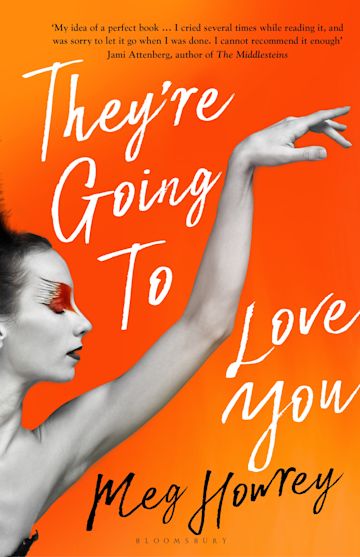

This is an excerpt from They’re Going to Love You, forthcoming in November 2022 from Bloomsbury in the UK and Doubleday in the USA.