The subjects of Debmalya Ray Choudhuri are encountered by a viewer who appears washed up in a new city. They play ironically with social codes and are equal parts desiring and reticent, longing and withdrawn. Flirtation and its denial are the dominant mood of these photographs: Touch me not, they seem to say to us. Isn’t this the look that Choudhuri’s lying model gives? The head rests on sheets ruffled into folds by the erotic grip of a hand; the arms flex just slightly. The presence of another person at the scene is suggested. The image invites you to imagine their position and to mentally assume it. Look again and you see that the model’s eyes are open, which is not unexpected, given the circumstances. But in the gaze, there is something strange: not rapt sexual pleasure, but circumspection, even hostility, directed outwards. Suddenly you feel yourself pulled from the position of the participant – thrown off the model’s back, so to speak – and out of the tableau entirely. It’s a look that says, Desire is here, and you have no part of it.

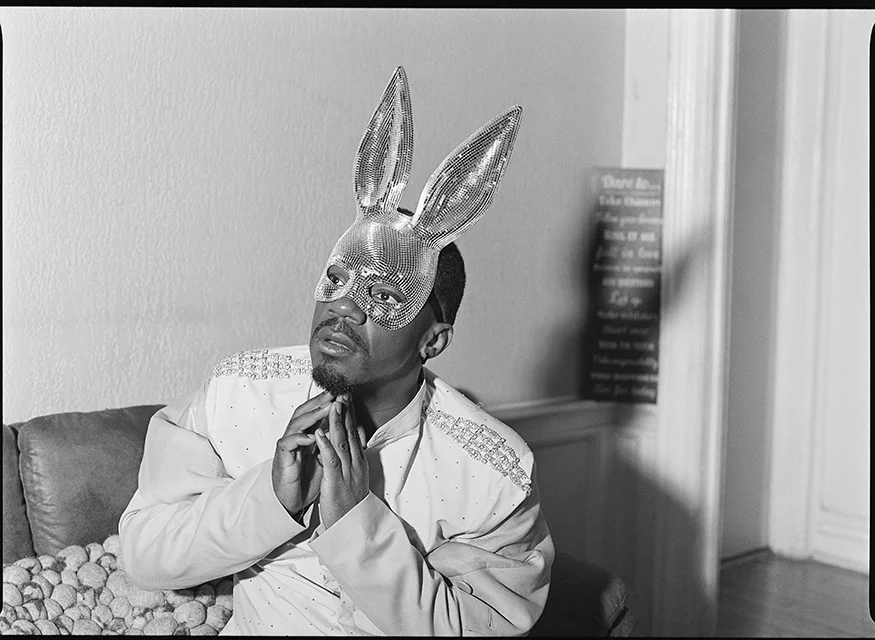

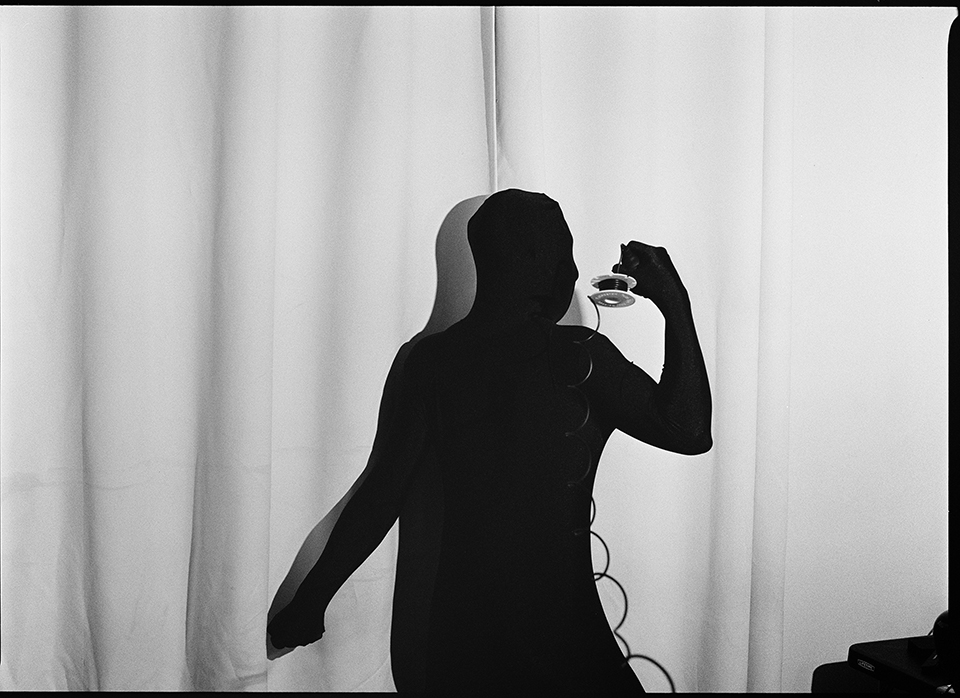

Choudhuri has said he met many of his models online, on Craigslist to be specific. His photos share the intimacy of a rendezvous with a stranger. These are people willing to show you their naked body, but not very much else. In one image, a man shakes his hips in a dancing motion, his body bending into the shadows of the photograph which obscure his face and engulf much of his right side. Superficially, what we’re seeing here is some bravura: a bit of queer machismo, maybe. But it is, of course, the anonymity of the darkness – as well as the encounter with a stranger – which makes the self-confidence of the sitter possible in the first place. The slow shutter speed both blurs the image and creates a space in which a form of self-expression – fully exposed yet obscured – can exist.

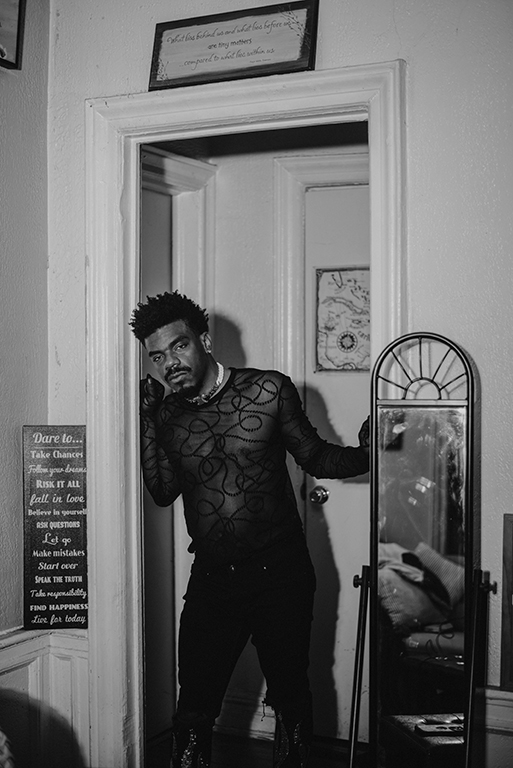

Largely, Choudhuri’s images track onto a certain kind of immigrant experience, albeit not in the hackneyed ways that these things are often discussed. This is an experience of being confronted with a place which has its own rules, to which newcomers must bend. Many of the models seem to have their own agenda. Their poses are not the product of the comfort of familiarity, in contrast to, for instance, Peter Hujar’s portraits of Manhattan intimates. Each subject has something they are willing to reveal about themselves, a hard constraint with which Choudhuri seems to have to make do. Much like a new city, the models come as they are and must be navigated rather than shaped. This is what we can see in the image of the woman who kneels with her back to the camera and her face shrouded by hair she has flung over it. Again, the gesture is that of superficial self-confidence made possible by an illusion of control. Her hands appear to tease seductively at her body. But this is a contrivance, like the props placed in a PG-13 film to cover up nudity. The whole image swims in a space of ambivalence: who has drawn the boundary here, the model or the photographer?

Choudhuri’s world is one from which concerns about authenticity and sincerity, as well as naïveté and cynicism, have long ago taken flight. In one image, two people walk along a New York street, perhaps thirty feet separate them. They seem indifferent, not just to one another, but to their surroundings, which are unremarkable with the exception of two lines of graffiti at the centre of the photo and written on a white residential picket fence. It reads, simply, remain free. The injunction is unbearably empty. It is hard to imagine a context in which anyone would say it, let alone write it. The image as I’ve described it would seem saturated with irony, but the people in the photograph pay it no mind. The words are as much a part of the general sense of obliviousness as the two passers-by.