‘I didn’t die,’ says Jeanmaire proudly. ‘They wanted me to, but I wouldn’t do them the favour.’

It is evening. We are alone in his tiny flat on the eastern outskirts of Bern. He is cooking cheese fondue for the two of us. On a shelf in the kitchen stand the steel eating bowls he used in prison. Why does he keep them?

‘For memory,’ he replies.

In the tiny corridor outside hang the dagger and sabre that are the insignia of a Swiss army officer’s dress uniform. The drawing room is decorated with a reproduction medieval halberd and his diploma of architecture dated 1934. A signed photograph from General Westmoreland, commemorating a goodwill visit to Bern, is inscribed ‘General, Air Protection Troops’, Jeanmaire’s last appointment.

‘Of course there were some of my colleagues who got nothing,’ he says slyly, indicating that he was singled out for this distinction.

He has decided it is time for a drink. He drinks frugally these days, but still with the relish for which he is remembered.

‘I permit myself a little water,’ he announces. Prussian style, he stiffens his back, raises his elbow, whips the cap off the whisky bottle I have brought him and pours two precise shots. He adds his water; we raise our glasses, drink eye to eye, raise them again, then perch ourselves awkwardly at the table while he rolls the whisky round his mouth and declares it drinkable. Then he is off again, this time to the oven to stir the cheese and – as a trained and tried military instructor as well as judge – lecture me on how to do it on my own next time.

On the desk, and on the floor, and piled high against the wall, papers, files, press cuttings, mounds of them, mustered and flagged for his last campaign.

It is a journalistic conceit to pretend you are unmoved by people. But I am not a journalist and I am not superior to this encounter. Jean-Louis Jeanmaire moves me deeply and humorously and horribly.

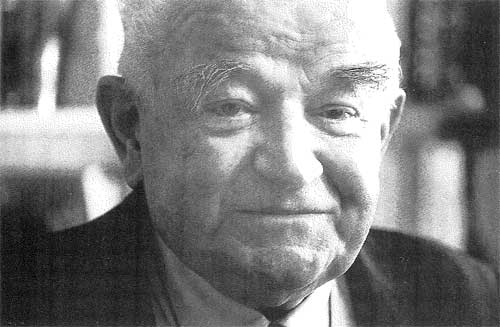

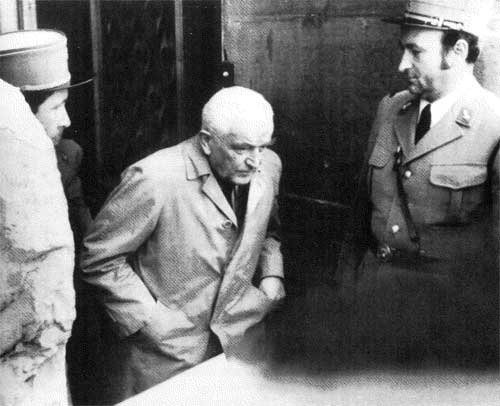

Jean-Louis Jeanmaire photographed in his apartment in the suburbs of Bern, 8 January 1991

Jeanmaire is not cut out to be a mystery, least of all a spy. He is not cut out to be a Swiss, for his feelings are written all over his features, even when he is trying to hide them, and he would be the worst poker player in the world. He is broad-faced and, for a seemingly aggressive man, strangely vulnerable. He has the eyebrows of an angry clown. They lift and scowl and flit and marvel with every stray mood that passes over him. His body too is seldom reconciled. He seems to come at you and retreat at the same time. He is short and was once delicate, but striving has made a bull of him. His brief, passionate gestures are the more massive for being confined in a small room. Wherever you are with him in his life – whether in his childhood, or in the army, or in his marriage, or in court, or in prison – you feel in him, and sometimes in yourself as well, the need for greater space, more air, more distance.

‘I had no access to top secret information!’ he whispers, with an emotional implosion that his body seems hardly able to contain. ‘How could I have betrayed secrets I didn’t know? All I ever did was give the Russians harmless bits of proof that Switzerland was a dangerous country to attack!’ A wave of anger seizes him. ‘C’était la dissuasion,’ he bellows. He is wagging his finger at me. His brows are clamped together above his nose. ‘My aim was to deter those mad Bolsheviks at the Kremlin from mounting an assault against my country! I showed them how expensive it would be! What is dissuasion if the other side is not dissuaded! Denissenko understood that! We were working together against the Bolsheviks!’

His voice drops to make the point more gently: ‘I was never a traitor. A fool maybe. A traitor, never!’

He has no time between moods. He has no time. He is pursuing justice every moment that is left to him. He can act and mime. He can camp and scorn and laugh. He has the energy of a man half his eighty years. One minute he is squared at you like a boxer; the next all you have to look at is his soldier’s back as, toes and heels together, he bows devotionally to light the candles on the tiny kitchen table. He lights them every day in memory of his dead wife, he says: the same wife whom he never once blamed for sleeping with his nemesis, the Soviet military attaché and intelligence officer Colonel Vassily Denissenko, Deni for short, who was stationed in Bern in the early sixties and effortlessly recruited Jeanmaire as his source.

He waves out the match. He has the tiny fingers of a watchmaker. ‘But Deni was an attractive man!’ he protests, as his far-off, pale eyes brim again with love remembered, whether for his wife or for Deni or for both of them. ‘If I’d been a woman I’d have slept with him myself!’

The statement does not embarrass him. For all that has been done to him, Jeanmaire is a lover still: of his friends, dead or alive, of his several women and of his erstwhile Russian contacts. The ease with which a man so deceived in his loyalties continues to give his trust is terrifying. It is impossible to listen to him for any time and not wish to take him into your protection. Deni was handsome! he is insisting. Deni was cultivated, charming, honourable, a gentleman! Deni was a hero of Stalingrad, he had medals for gallantry, he admired the Swiss Army! Deni was no Bolshevik: he was a horseman, a tsarist, an officer of the old school!

Deni, he might add, was also the acknowledged Resident of the GRU, or Soviet Military Intelligence Service, poor cousin of the KGB. But Jeanmaire doesn’t seem to care. The first time he even heard of the KGB, he insists, was when he was cataloguing books for the prison library. The GRU remains even more remote from him. He swears that throughout his entire military career, he never had the least training in these bodies.

And Deni was faithful to the end, he repeats, driving his little fist on to the table like a child who fears he is unheard: the end being twelve years in solitary confinement in a cell ten feet by six, after 130 days of intermittent civilian and military interrogation while under arrest, followed by a further six months’ detention while awaiting trial and a closed military tribunal that lasted barely four days. Its findings are still secret.

‘When they arrested me, Deni wrote a letter from Moscow to the Soviet Literary Gazette, describing me as the greatest anti-Communist he had ever known. The letter was published in the Swiss press but never referred to at my trial. That was exceptional, such a letter. Deni cared very much about me.’

That is not exactly what Denissenko wrote about him, but never mind. He described Jeanmaire as a nationalist and patriot, which is probably how Denissenko regarded himself also.

And still the anguished eulogy flows on. Deni never pressed him, never tried to squeeze anything out of him he didn’t want to give. Ergo – Deni was an honourable man! Not so honourable that Jeanmaire would let Deni pay for drinks or that he could accept an envelope of money from him or even that he could let Deni get a sight of Jeanmaire’s signature on a letter, but honourable all the same: ‘Deni was a man of heart, a brother officer in the best sense!’

Above all, Deni was noble. Jeanmaire awards this word like a medal. Jeanmaire has been prejudged, reviled and incarcerated. He has come as near to being burned as a witch as modern society allows. But all he asks is that, before he dies, the world will give him back his own nobility. And I hope it will. And so would all of us. For who can disappoint a man of such infectious and vulnerable feeling?

To the suggestion that he might have been jealous of his wife’s lover, Jeanmaire expresses only mystification.

‘Jealousy?’ he repeats, as the nimble eyebrows rush together in disapproval. ‘Jealousy? Jealousy is the vice of a limited man, but trust –’

We have struck his vanity again, his tragic, childish, prickly vanity: Jeanmaire is not a limited man, he would have me know! And his wife was a pure, good, beautiful woman and, like Deni, faithful to the end! Even though, in his wife’s case, the end came sooner, for she died while he was still in prison. Deni’s charm, whatever else it had going for it, did not come cheap.

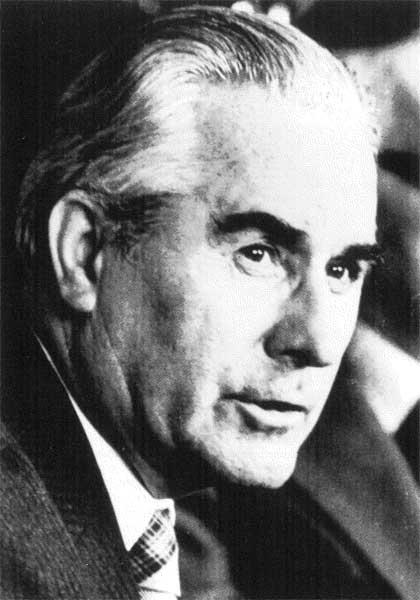

From the pile of cuttings Jeanmaire extracts a muddy photograph of the great man, and I try hard to imagine his allure. Or was the allure actually all on Jeanmaire’s side, and was Jeanmaire the one person who never knew it? Alas, Russian officers are seldom photogenic. All I see in Deni is a grey-suited, doughy-faced military bureaucrat of no expression, looking as if he would prefer not to have been photographed at all. And Jeanmaire, this un-Swiss Swiss, beaming as if he has just won the Derby.

Let me be a journalist for a moment. Jean-Louis Jeanmaire was born in 1910 in the small industrial town of Biel in the canton of Bern, where they do indeed make, among other things, the watches that remind me of his little hands. Biel is bilingual, German and French. So is Jeanmaire, though he regards French as his first language and speaks German with a grating, nasal pseudo-Prussian accent that to my ear is not at all Swiss, but then I was never in the Swiss Army. If there were such a thing as German Canadian, I am thinking as I listen to the rolled rs and saw-edged as, that is what Jeanmaire would be speaking. His father was an arch-conservative of chilling rectitude. Like Jean-Louis after him, he was a chartered architect. But by passion he was a Colonel of Cavalry and Commandant of Mobilization for the town of Biel. In a country condemned to peace, the infant Jeanmaire was thus born a soldier’s son and longed to be a soldier. He was four when the First World War broke out, and he has a clear memory of his papa standing in uniform beside the Christmas tree and of his great and good godfather Tissot, also in uniform, dropping in to visit.

‘Such a beautiful officer,’ Jeanmaire recalls of his godfather Edouard Tissot, almost as if he were talking about Deni.

Tissot was also beautiful without his uniform, apparently. When Jeanmaire visited him in his spacious apartment, he would likely as not find his godfather wandering around it naked. But no, Tissot was not homosexual! he cries in disgust, and neither was Jeanmaire! This nakedness was Spartan, never sexual.

Yet beside this image of military glory, Jeanmaire has a second and contrasting early memory that reflects more accurately the social upheavals of the times: namely of the Swiss General Strike of 1918, when the ‘Bolsheviks of Biel’ derailed a train in order to barricade the street, then hoisted the red flag on the capsized engine. Their violence against property and their lack of discipline appalled the young Jeanmaire, and his love of the army, if possible, increased. Even today, given the chance, Jeanmaire would make an army of the whole world. Without his army, it seems, he is in his own eyes a man of no parentage.

Jeanmaire is nothing if not the creature of his origins. For those who know Switzerland only for its slopes and valleys, Swiss militarism, if they are aware of it at all, is a harmless joke. They make nothing of the circular steel plates in the winding mountain roads, from which explosive charges will be detonated to seal off the valleys from the aggressor; of the great iron gateways that lead into secret mountain fortresses, some for storing military arsenals, others for sitting out the nuclear holocaust; of the self-regarding young men in officer’s uniform who strut the pavements and parade themselves in tea shops at weekends. They are unaware of the vast annual expenditure on American tanks and fighter aircraft, early-warning-systems, civil defence, deep shelters and (with 625,000 troops from a population of 6,000,000) after Israel the largest proportionate standing army in the world, costing the Swiss taxpayer 18 per cent of his gross national budget – it has been as high as thirty – or 5.2 billion Swiss francs or £2.1 billion a year. If their Alpine holidays are occasionally disturbed by the scream of low-flying jets or bursts of semi-automatic fire from the local shooting range, they are likely to dismiss such irritations as the charming obsessions of a peaceful Lilliput with the grown-up games of war.

And to a point, the Swiss in their dealings with the benighted foreigner encourage this view, either because as believers in their military ethic they prefer to remain aloof from frivolous explanation, or because as dissenters they are embarrassed to admit that their country lives in a permanent, almost obsessive state of semi-mobilization. For better or worse, Switzerland’s military tradition is for many of her inhabitants the essence of Swiss nationhood. And the chain of influence and connection that goes with it is probably the most powerful of the many that comprise the intricate structure of Swiss domestic power.

To its more radical opponents, the Swiss Army is quite baldly an expensive weapon of social suppression, an insane waste of taxpayers’ money, which recreates in military form the distinctions of civilian life. But to its defenders, it is the very spirit of national unity, bridging the linguistic and cultural differences between Switzerland’s ethnic groups and keeping at bay the swelling numbers of immigrants who threaten to dilute the proud and ancient blood of free Switzerland. Above all, say its defenders, the army deters the foreign adventurer. Just as apologists of the nuclear deterrent insist that the bomb, by its existence, has ensured that it will never be used, so supporters of Swiss militarism claim that the army has secured their country’s neutrality – and hence survival – through successive European wars.

Jean-Louis Jeanmaire – who still prides himself on having persuaded incarcerated conscientious objectors to change their minds – has subscribed passionately to this gospel since childhood. He had it preached to him by his father and again by his godfather Tissot. In the same breath they taught him the equally fervent gospel of anti-socialism. ‘Good’, says Jeanmaire, meant ‘patriot and militarist’. ‘Bad’ meant ‘anti-militarist and socialist.’

But the small town of Biel did not at all share the reactionary visions of Tissot, Colonel Jeanmaire and his son. Its inhabitants were mostly workpeople. When the railway workers marched in support of the strike of November 1918 – in the same days in which Jeanmaire witnessed the overturning of the train – the army dealt with them swiftly, tearing into the crowds and shooting one man dead. But the response of Jeanmaire’s father and his comrades, he says, was to rally a contingent of technical students to keep the gas and electricity works going, and arm the bourgeoisie against the rabble. Interestingly, local historical records award no such role to Jeanmaire’s father, but say that the strike was broken by imported Italian labour. But whatever his father’s contribution to the suppression might have been, his conservative posture did not make life easy for the young Jeanmaire when the time came for him to attend the local school. From his first day, he says, beatings by staff armed with sticks and the inner tubes of car-tyres became his fare. When he was unruly, the diminutive Jeanmaire was strapped to a school bench: ‘I was the smallest but I wasn’t the most stupid,’ he says grimly.

Some boys in this situation might have learned to keep their opinions to themselves, or prudently converted to their oppressors’ views. Not Jeanmaire. Always one to speak his mind, he did so more loudly, in defiance of what he regarded as the prevailing cant. Both at school and afterwards, he learned to count on his own judgement and assail mediocrity wherever he found it, whether it was above him or below him on the ladder of beings.

And this attitude stayed with him through his adult life – through the architectural studies on which he hurled himself with impressive result as a prelude to enlistment and into his career as an infantry instruction officer, which he pursued on the orders of his godfather Tissot, who told Jeanmaire that if he joined the artillery he would never talk to him again.

At first, Jeanmaire’s career proceeded well. In 1937, after the usual probationary period, he made instructor, rose to captain three years later and major after another seven. During the Second World War he saw service on the Simplon and in the canton of Wallis, and in 1956 he was made lieutenant-colonel and given his first regiment.

Yet throughout his steady rise, Jeanmaire’s reputation as a big mouth would not go away, as his army record testifies in its otherwise quite favourable account of him: Jeanmaire was ‘intelligent, lively’, but spoke ‘too much and too soon’. In his work as an infantry instructor, he ‘lacked respect and picked quarrels with his superiors’. He was ‘qualified technically but not personally’ to command a training school. On one occasion, in 1952, he was even given eight days’ punishment arrest ‘for insulting officers of a battalion placed under his command’ during manoeuvres – though according to Jeanmaire, all he did was tick off a member of Parliament for not wearing his helmet and call a machine-gunner an arsehole for nearly mowing down a group of spectators.

True, Jeanmaire had his supporters, even if their admiration of him was played down in the Army’s self-serving portrait of his inadequacies. To some of his superiors, he was a capable officer, an inspiration to his men, energetic, good fun. Nevertheless, the abiding impression is of a man impatient of fools, pressing too hard against the limitations of his rank and professional scope. At best, he comes over as a kind of miniature Swiss Lee Kwan Yew, thrusting to express great visions in a country too small to contain them.

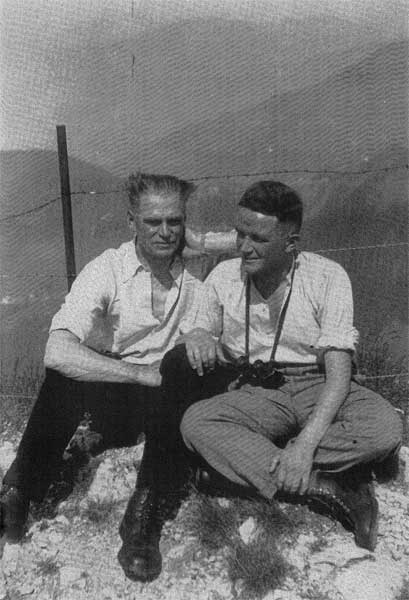

Jeanmaire, having recently been promoted to major, in 1943

Jeanmaire’s accusers, of course, had every reason to present his military career in a poor light, for they were stuck for a motive. They had looked high and low for the thirty pieces of silver, but all they had found was a handful of small change. And not even the most implacable of Jeanmaire’s enemies could pin secret Communist sympathies on him.

So finally they fixed upon Jeanmaire’s transfer to Air Defence in 1956 as the moment of his turning; followed by his being passed over, in 1962, for the appointment as Chief of Air Defence and Territorial Services, obliging him to wait another seven years, by which time the two responsibilities had been separated, and Jeanmaire got Air Defence only. Jeanmaire, it was reasoned, was ‘disappointed and traumatized’, first to leave the glorious infantry for the unregarded pastures of Air Defence, then to see a lesser man promoted over him. Jeanmaire denies this adamantly: perhaps too adamantly. The army had always been good to him, he insists; he had status, and he was on the guest list for Bern’s diplomatic round of military and service attachés; and in 1969, when he finally made it to brigadier, he got his apartment in Bern as well.

And he had a wife, of whom he still says little, except that she was the soul of loyalty and faithful to the end; and that she was beautiful, which indeed she was; and that he lights a candle to her memory each day.

The army matters to Jeanmaire above everything. Even today. Even when he lay in the deepest pit of his misfortune, his faith in it burned on. He was in prison awaiting trial when, on 7 October 1976, Kurt Furgler, the Swiss Federal Minister of Justice, rose in Parliament to denounce the ‘treasonable activities’ of Jeanmaire, his ‘disgraceful attitude’ and his betrayal of ‘most secret documents relating to war mobilization plans’. The next day, Switzerland’s most strident tabloid, Blick, branded Jeanmaire ‘Traitor of the Century’ in banner headlines and ran photographs of the villain and his accuser on the front page. Three months later, the Federal President Rudolf Gnägi, addressing a meeting of his own party, confessed his deep disappointment that ‘such base actions could be committed by such a high officer’, and demanded ‘the full severity of the law’. There are Western countries where such words would have rendered a trial impossible, but Switzerland is not among them. The Swiss may have signed the European Declaration of Human Rights, but they have no law that prevents the public prejudgement of those awaiting trial. Furgler also denounced Jeanmaire’s wife, stating that she had knowledge of her husband’s treasonable activities and in the early years had assisted him. (The charges against Frau Jeanmaire were eventually dismissed.) The Swiss insurance company Winterthur, from which the Jeanmaires had rented their apartment, also preferred not to await the verdict of the military court, but gave them notice, forcing his wife on to the street.

Yet among all these calculated humiliations, what hurt him most and hurts him this evening is that his beloved army, also before his trial, caused his pension to be withdrawn ‘in eternity’. The reason, according to one reputable paper of the day, was Volkszorn, popular fury. ‘Our offices were exposed to pressure by angry citizens. A flood of letters demanded that Jeanmaire be paid no further money,’ a spokesman for the federal pensions agency explained.

For a moment, it is as if the pale baby eyes are presuming to weep without his permission. They fill, they are about to brim over. But the old soldier talks brusquely on, and the tears dare not fall.

‘That was a crime as never before,’ he says.

‘In prison I was never a slave but I obeyed!’ Jeanmaire declares, hastening once more to the defence of old friends: ‘No, no, they were good fellows, my fellow prisoners! I never had a bad scene! I was never set upon or insulted for what I was supposed to have done. I never felt threatened by a single one of the prisoners I met! I always made a point of warning the young ones of the perils of prison. I was a father to them.’

Seated at his little table, eating his fondue, we become cellmates, sharing our hoarded rations by candlelight.

He is talking of the first shock of imprisonment: the terrible first days and nights.

‘They took my watch away. They thought I could kill myself with it. It’s very bad to be in solitary without a watch. A watch gives rhythm to your day. When you are free, you go to the phone, the lavatory, the kitchen, the bookshelf, the garden, the café, the woman. The watch tells you. In prison, without a watch these instincts become clamorous and confused in your head, even if you can’t obey them all the time. They’re freedom. A watch is freedom.’

The front page of Blick on 8 October 1976 – ‘The Traitor of the Century.’ ‘Former Brigadier Jean-Louis Jeanmaire (66)’ the article says, ‘told the Soviets everything, everything, he knew! That’s what Minister of Justice Furgler, ashen-faced and visibly shaken, had to tell a shocked Parliament yesterday.’

But Jeanmaire’s sanity, despite the harrowing assaults on it, seems as pristine as the polished steel bowls he keeps from prison. He has an extraordinary memory for dates and places and conversations. He has been interrogated by a rotating troupe of professional performers for months on end: policemen, lawyers, bit-players from the demi-monde of spying. He has been interrogated in prison hospital, on what should have been his deathbed. Since his release, he has given interviews on television, to the printed press and to the growing number of concerned Swiss men and women in public life who begin to share his view that he is the victim of a great injustice.

There are evasions, certainly. You hit them like fog patches along an otherwise clear road: willed unclarities where he is being merciful to himself or to third parties. For example, when you touch upon the delicate matter of his wife’s affair with Denissenko – when did it start, please? How long did it last, please? When did he first know of it and what part did it play in his collaboration? For example, the number of encounters he had with his successive Soviet contacts, and exactly what information or documents were passed on this or that occasion? We are talking, you understand, not of the discovery of the H-bomb, but of how the Swiss people would respond to the improbable sight of an invasion force of Soviet tanks rumbling up Zürich’s Bahnhofstrasse.

Most difficult of all is to pin down Jeanmaire’s own degree of awareness – consciousness, as the spies call it – as he slid further and further down the fatal slope of compliance. There we are dealing not merely with self-deception at the time of the act, but with fifteen years of subsequent self-justification and reconstruction, twelve of them in prison, where men have little to do except relive, and sometimes rewrite, their histories.

Yet the consistency of detail in Jeanmaire’s story would be remarkable in any story so frequently retold. Jeanmaire ascribes this to the disciplines of his military training. But the greater likelihood seems to be that he is that rarest of all God’s creatures: a spy who, even when he wishes to deceive, has not the smallest talent to do so.

Under interrogation, Jeanmaire was an unmitigated disaster; the tortures of sudden imprisonment worked wonderfully and swiftly on such a thrusting and sociable spirit.

‘There were moments when, if I had been accused of stabbing my wife seven times, I would have said, “No, no, eight times!” Again and again they promised me my freedom: “Admit this and you are free tonight.” So I admitted it. I admitted to more than I had done.

‘When you are first locked in a cell you undertake a revolution against yourself. You curse yourself, you call yourself a bloody fool. You’re the only person you blame. You protect yourself, then you yield, then you enter a state of guilt. For instance, I felt guilty that I had ever spoken with Russians at all. I believed I was guilty of meeting them, even though it was my job. After that came the optimism that the tribunal would deliver the truth, and they encouraged me to believe this. I had been a judge myself, at fifty trials. I believed in military justice. I still do. What I got was a butchery.’

He is no longer alone in this conviction. Today, the witch-burners of fifteen years ago are feeling the heat around their own ankles. The belated sense of fair play which, in Switzerland as in other democracies, occasionally asserts itself in the wake of a perceived judicial excess, is demanding to be appeased. A younger Switzerland is calling for greater openness in its affairs. An increasingly outspoken press, a spate of scandals in banking and government, now lumped together as ‘the Kopp affair’ after the first woman deputy in the Swiss government and Minister of Justice who fell from grace for warning her lawyer husband that he risked being implicated in a government inquiry into money-laundering – all these have beaten vigorously on the doors of secret government.

The new men and women are impatient with the old-boy networks of informal power, and suddenly public attention is fixing its sights upon the most elusive network of them all: the Swiss intelligence community. It is not Jeanmaire but the ‘snoopers of Bern’ and the professional espionage agencies who are being accused of betraying their secrets for profit, of spying on harmless citizens, of maintaining dossiers in numbers that would embarrass a country five times Switzerland’s size and of fantasizing about non-existent enemies.

And as the decorous streets of Bern echo with youthful protestors demanding greater glasnost, it is the unlikely figure of Jeanmaire, the arch-conservative and militarist, the man who for so long hated popular revolt, who now walks with them in spirit, not as ‘the traitor of the century’ but as some flawed, latter-day Dreyfus, framed by devious secret servants to cover up their own betrayal. In the next few weeks he will hear whether he has won a reassessment of his case.

Yet whatever the final outcome, the story of Jean-Louis Jeanmaire will remain utterly extraordinary: as a tragi-comedy of Swiss military and social attitudes; as an example of almost unbelievable human naïvety; and as a cautionary tale of an innocent at large among professional intelligence-gatherers. For Jeanmaire, by any legal definition, was a spy. He was seduced, even if he was his own seducer. He did pass classified documents to Soviet military diplomats, without the knowledge or approval of his superiors, even if they were documents of little apparent value to an enemy. He did receive rewards for his labours, even if they were trivial, and even if the only real satisfactions were to his ego. Immature he certainly was, and credulous to an extraordinary degree. But he was no child. Even by the time of his recruitment, he was a full colonel with thirty years of soldiering in his rucksack.

So what we are talking of is not so much Jeanmaire’s guilt in law, as the price he may have paid for crimes he simply could not have committed. And what we are observing is how a combination of chance, innocence and overbearing vanity precipitated the unstoppable machinery of one man’s destruction.

‘My two great crimes are as follows,’ Jeanmaire barks, his delicate fingers outstretched to count them off, while he once more stares past me at the wall. ‘One, I had character weaknesses. Two, I had been a military judge. Finish.’

But he has left out his greatest crimes of all: a luminous, fathomless gullibility, and an incurable affection for his fellow man, who could never sufficiently make up to him the love he felt was owed.

Marie-Louise Burtscher prior to meeting Jeanmaire. The soldier in uniform was her first fiancé.

To describe Jeanmaire’s courtship and marriage is once again to marvel at the cruel skein of coincidence that led to his destruction. For one thing is sure: if Jeanmaire had not, in June 1942, fallen innocently in love with one Marie-Louise Burtscher, born in Theodosia, Russia, on 12 October 1916, and if they had not married the following year, he would now be living out an honourable retirement.

He met her while he was travelling on a train from Bern to Freiburg. She entered his compartment and sat down: ‘Lightning struck, I was in love!’ They talked, he chattered army stuff, he could think of nothing better. She was working as a secretary in the Bern bureaucracy, she said; and yes, he could take her out to dinner. So on the next Wednesday, he took her to the Restaurant du Théâtre in Bern, and of course he wore his uniform.

‘Thus began the great love. I don’t regret it. She was a good, sweet, dear comrade.’

Comrade is the word he uses of her repeatedly. But it was her past, not her comradeship, that became the chance instrument of Jeanmaire’s undoing. Marie-Louise Burtscher was the daughter of a Swiss professor of languages who was teaching in Theodosia at the time of the Revolution. So it was from Theodosia, in 1919, that the family fled to Switzerland, penniless, expelled by the Bolsheviks. The professor’s last days were spent working as a translator and he was dead by the time Jeanmaire met Marie-Louise.

But Marie-Louise’s mother, Juliette, survived to exert a great and enduring influence on Jeanmaire – greater, one almost feels, than her daughter’s. Jeanmaire not only undertook responsibility for her maintenance but spent much time in her company. And Juliette talked – endlessly and glowingly – of the old Russia of the tsars. The Bolsheviks were brutes, she said, and they had driven her from her home, all true. But the Bolsheviks were not the real Russians. ‘The real Russians are people of the land,’ she told Jeanmaire, again and again. ‘They’re farmers, peasants, intelligent, cultivated, very pious people. My greatest wish is to return to Russia to be buried.’

Thus by the sheerest chance Juliette became another of Jeanmaire’s life instructors, taking her place beside his father and his godfather Tissot. And her fatal contribution was to instil in him a burgeoning romantic love for Mother Russia and an even greater hatred, if that were possible, for the rapacious Bolsheviks, whether of Biel or of Theodosia. ‘Juliette loved Russia with her soul,’ says Jeanmaire devoutly. And it is not hard to imagine that, as ever when he had identified an instructor, he struggled to follow her example.

The marriage began in Lausanne and followed Jeanmaire’s postings until the couple returned to Lausanne to settle permanently. In 1947, Marie-Louise bore a son, Jean-Marc, now working for a bank in Geneva. In return for her keep, Juliette kept her daughter company during Jeanmaire’s absences and helped look after the child. The couple spent about one third of each year together – Jeanmaire was for the rest of the time with the army. ‘My wife never intrigued, was not vain. One noticed in her that she had begun life from the bottom, as a poor kid. She had no girl-friends. She was a woman who was content with her own company. She read a lot, walked and was a good hostess.’ And he uses the word again, this time more clearly: ‘She was less a wife than a comrade.’

And that is all he likes to say about her, except to tell you that his lawyer has advised him not to say any more, and that he, Jeanmaire, doesn’t know why. It is quite enough, nevertheless, to set the stage for the appearance of Colonel Vassily Denissenko.

It is April 1959 in beautiful Brissago in the Italian part of Switzerland, and the Air Protection Troops of the Swiss Army are giving a demonstration under the able direction of Colonel Jeanmaire. All Bern’s foreign military attachés have been invited and most have come.

The climax of the demonstration, as is traditional in such affairs, comes at the end. To achieve it, Jeanmaire has ingeniously stage-managed the controlled explosion of a house at the lake’s edge. The bomb strikes, the house disintegrates, flames belch out of it, everyone inside must be dead. But no! In the nick of time, stretcher parties of medics have arrived to bring out the burned and bleeding casualties and rush them to the field hospital!

It is all splendidly done. Under cover of the smoke, Jeanmaire has introduced his ‘casualties’ from the safety of the water, in time for them to climb on to their stretchers and be ‘rescued’ from the other side of the house. The effect is most realistic. The distinguished guests applaud as Jeanmaire formally reports to his superior officer that the demonstration is at an end. When he has done so, Colonel Vassily Denissenko of the Soviet Embassy in Bern delivers a short speech of thanks and admiration on behalf of himself and his colleagues. For Denissenko, though newly arrived, is today by a whim of protocol, the doyen of Bern’s military attachés. His speech over, he turns to Jeanmaire and, in front of everyone, asks him, in jest or earnest, a very Russian question: ‘Tell me, Colonel, how many dead men were you allowed for the purposes of this demonstration?’

Jeanmaire’s reply, by his own account, was less than diplomatic: ‘We’re not living in a dictatorship here, as you are in Russia. We’re in democratic Switzerland and the answer to your question is “None”. I cannot allow myself a single wounded man.’

Denissenko makes no comment, and the party adjourns to Ponte Brolla for lunch at which Jeanmaire, still flushed with success, finds himself, thanks to the placement required of protocol, seated at Denissenko’s side. Here is Jeanmaire’s account of their opening exchange: ‘So that there is no misunderstanding, Colonel,’ Jeanmaire kicks off, ‘I don’t care for Soviets. I’ve nothing against you personally, since you yourself can’t do anything about the mess the Russians have brought upon the world, both in the Second World War and in the Bolshevik Revolution!’

Denissenko asks why Jeanmaire has such a hatred of the Russians.

‘Because of my parents-in-law,’ Jeanmaire replies, now in full sail. ‘They were thrown out of Russia in 1919 and had to flee to Switzerland. They arrived without a penny to their names. As a result, I’ve had to provide for them.’

And to this, Denissenko replies – spontaneously, says Jeanmaire – ‘That’s a terrible story. I don’t hold with that sort of behaviour either. You must never confuse the Bolsheviks with the Russians. The Bolsheviks are bandits.’

Jeanmaire is at once reminded of the stories told him by his late mother-in-law: ‘At this moment I recognized in him a tsarist officer,’ he recalls simply.

As to Denissenko, he may have recognized something in Jeanmaire also, for he soon returns to the subject of the injustice done to Jeanmaire’s parents-in-law: ‘We ought to put that right,’ he says. ‘The property should be given back. And you should receive something by way of compensation.’

But Jeanmaire still presses his attack. ‘And look here. What about that disgusting business in Budapest three years ago?’ he demands, referring to the Soviet repression of the Hungarian uprising.

Once again Denissenko is quick to parade his antipathy to the Bolsheviks: ‘I agree with you one hundred per cent. And let me tell you something else. In 1966, a certain Russian officer will be coming to Bern as military attaché with whom you should have no contact at all. He’s the man who organized the whole Budapest affair.’

And thus – says Jeanmaire – did Denissenko warn him against one Zapienko, who did indeed come to Bern in 1966, and Jeanmaire avoided him exactly as Deni had advised.

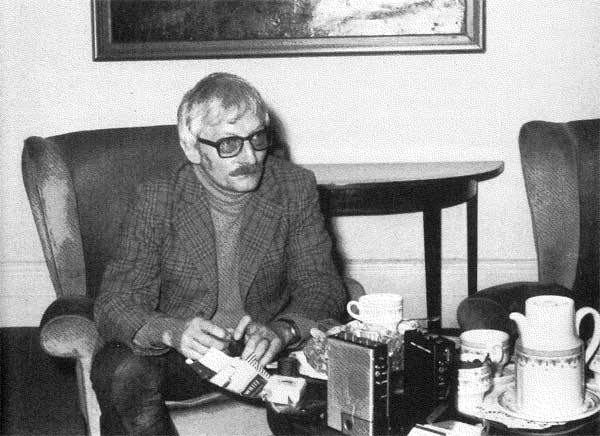

Jeanmaire with US General Westmoreland, in Switzerland, in 1969.

In terms of intelligence trade craft, the horseman Denissenko had thus far achieved a faultless round. He had presented himself as an anti-Communist. He had nimbly touched upon the possibility that Jeanmaire might be eligible to receive Russian money. He had left the door open for further contact. And by warning Jeanmaire against Zapienko, he had planted in him a psychological obligation to grant a favour or a confidence in return. Yet to this day, Jeanmaire seems unable to believe that Denissenko’s moves were no more than the classic passes of a capable intelligence officer.

‘He didn’t prod. He put out no hints,’ he insists. ‘He was correct in all respects. He had a great admiration for the Swiss Army.’

The meeting over, Jeanmaire hastened home to tell his wife the amazing news. His words, as he repeats them now, are like the headlong declaration of a young lover to his mother: ‘He’s exactly what Juliette your mother always loved! A real, fine tsarist officer! What a shame she’s no longer alive to meet him!’

Jeanmaire was so enthusiastic about Denissenko that he insisted that Marie-Louise accompany him the next month to a British diplomatic reception at Bern’s Schweizerhof Hotel in order that she could meet Denissenko for herself. So she went, and Jeanmaire hastened to introduce her to his discovery. Denissenko, speaking Russian, asked Marie-Louise whether she spoke Russian also. She understood the question and said no. After that, the two spoke German.

‘She saw in him someone who, like herself, had been born in Russia,’ says Jeanmaire, explaining his wife’s pleasure at this first encounter. And then: ‘You can never tell what goes on inside a woman’s head. Otherwise nothing happened.’

Speaking this way of his wife, Jeanmaire is once more too dismissive, too much on guard. There is another story here somewhere, but he is not telling it – certainly not to me, but perhaps not to himself either.

Throughout that same year Jeanmaire and Denissenko met at several receptions. Marie-Louise, according to Jeanmaire, came only once. Sometimes Denissenko’s wife was present – from Jeanmaire’s account of her, a pleasant, tubby, not especially pretty woman, a Russian babushka in the making. But the axis was undoubtedly between the men: ‘Deni was interesting to talk to and felt bound to me on account of the injustice done to my parents-in-law. Perhaps my wife was somewhere in the background of his mind. I don’t know. At that time, nothing had happened.’ And this is the second time that Jeanmaire has assured me that nothing has so far happened between Deni and Marie-Louise. How did he know? I wonder – unless he knows better? When did something happen? – and did he know then, too?

At one of these occasions, Denissenko suggested a lunch. Jeanmaire says that when he reported this in advance to his brigadier, which he invariably did throughout his liaison with the Russians, the brigadier wished him ‘bon appetit’.

The two men drove in Denissenko’s Mercedes to Belp on the outskirts of Bern, to the Hotel Kreuz, Denissenko’s choice. Over lunch, Denissenko first talked about the battle of Stalingrad, in which he had served as an air captain. He dwelt on the horrors and the heroism of war. Jeanmaire, the Swiss soldier, was thrilled by this vicarious experience of one of the great sieges of history. The conversation turned to the construction of the new Geneva-Lausanne autobahn through Morges and to the uses of autobahn underpasses as atomic air-raid shelters. Jeanmaire was impressed by Denissenko’s detailed knowledge of the Morges terrain. Denissenko drank no schnapps and little wine – on account, he explained, of his heart. Jeanmaire drank more freely, but not excessively. This is a regular refrain of Jeanmaire’s narrative. Other encounters followed through the next year, but it was not until a full two years after the Brissago meeting that the Jeanmaires invited Denissenko to dinner, as usual – says Jeanmaire – with the advance approval of his superiors.

Denissenko arrived by chauffeur-driven car, and he was glowing with excitement. The date was 13 April 1961. On the day before, Gagarin had become the first man to circle the earth in space. Deni’s elation was instantly matched by Jeanmaire’s. Unlike the Pentagon, which was having kittens at the news, Jeanmaire appears to have been thrilled by Russia’s triumph. The party set off for Savigny outside Lausanne for dinner, and the evening was spent discussing the space race. The local police chief walked in and, at Jeanmaire’s invitation, joined them for a drink.

Jeanmaire on principle always paid his own tab when he was out with foreign attachés, and he paid it that night. After dinner, the party repaired to a Bern nightclub, the Tabaris, where Jeanmaire presented Denissenko to the manageress. ‘I was proud to be able to show myself with this man. He was very presentable: always well dressed – we were in civilian clothes – discreet but well chosen. He was a Gorbachev. When I think of Denissenko today, I see Gorbachev. I experienced glasnost twenty-five years ahead of its time.’

Jeanmaire recalls that Denissenko danced with Marie-Louise. The drinking, in deference to Denissenko’s heart, was again moderate, he insists. All the same, it was a long, late, jolly evening, and what is significant in retrospect is that Denissenko, the professional GRU officer, made no attempt in the months that followed to build on it. If he was setting Jeanmaire up for a clandestine approach, he was playing a long game.

On the balcony outside Jeanmaire’s flat at the end of May 1964. Marie-Louise is on the left; Vassily Denissenko’s wife is on the right.

There are several possible explanations for Denissenko’s apparent reluctance to develop Jeanmaire as a secret source. The first is that having taken a close look at his man he had decided, with reason, that Jeanmaire simply didn’t know enough to be worth the candle, either as a present source or as a future prospect to be directed against a better target. Jeanmaire was discernibly approaching his professional ceiling, after all, and it was not, from the point of view of Soviet intelligence priorities, a sexy one. Other explanations lie in the still impenetrable marshes of the Soviet espionage mentality. No potential recruit of the sort Jeanmaire had now become could be approached without detailed orders from Moscow. Even in the GRU, which never approached the KGB in professionalism or sophistication, the choice of restaurant, the allocation of expenses, topics of conversation for the evening – all would have been ordained in advance by Denissenko’s Moscow masters.

And it is beyond doubt that any effort to shift Jeanmaire from the status of ‘legal’ to ‘illegal’ collaborator would have been preceded by a ponderous appraisal of the risks and merits. Is he a plant, they will have asked themselves, in wearying evaluation sessions? A man so forthcoming might certainly have looked like one. Is he a provocation to secure Denissenko’s expulsion or sour Soviet-Swiss relations? Does he want money? If so, why does he insist on paying his own way? And if not, how is this passionate anti-Communist motivated? The astute Denissenko had not, it seems, detected in Jeanmaire those vengeful feelings against his superiors that became such a feature of the later case against him.

And perhaps – because of the delicacy of the diplomatic situation – the GRU may even have swallowed its pride and called in the KGB, who counselled caution and delay. Or perhaps the KGB gave different advice: perhaps they said, ‘Keep Jeanmaire in play, but slowly, slowly. One day we may need to fatten him as a sacrificial lamb.’

All that is certain is that for several months Denissenko made no move towards Jeanmaire. He spent much time in Moscow, allegedly on health grounds, and no doubt when he conferred with his colleagues at headquarters the pace and progress of Jeanmaire’s cultivation were discussed: even if he can hardly have rated high on Moscow’s shopping list.

Then in March 1963, Denissenko and the Jeanmaires got together again, once more for dinner, and the topic this time turned to a Swiss military exercise which had taken place a few weeks before. A friendly dispute arose between the two men. Denissenko, who appeared excellently informed, insisted that Swiss military planning leaned heavily on NATO support. Jeanmaire, as ever the champion of Swiss neutrality, vigorously denied this, and in order to prove that the Swiss integrity was still intact, he says, he offered to show Denissenko the organization plan of staff and troops at corps and division levels, from which it would be clear that the army maintained no NATO liaison of the sort Denissenko suspected. The army, of course, most certainly did maintain such liaison and would have been daft not to, though officially it was denied. And Jeanmaire knew it did, but the organization plan did not reveal this. Ironically, therefore, what Jeanmaire was offering Denissenko in this case was not dissuasion at all but Swiss military disinformation.

But Denissenko in return seems not to have taken Jeanmaire up on his offer. Why not? Too risky? Or simply a warning from Moscow to lay off?

The only known photograph of Marie-Louise Jeanmaire and Vassily Denissenko – on the Jeanmaires’ balcony.

Three months later, however, Jeanmaire bumped into Denissenko at a cocktail party given by the Austrian military attaché and invited him to his apartment in Lausanne. Three days after that, in the company of Marie-Louise, Denissenko and Jeanmaire ate a meal at Lausanne’s railway-station buffet, then went on to the Jeanmaire’s apartment where Jeanmaire handed over a photocopy he had made of the promised document, or part of it.

The document was graded ‘for Service use only’ or as the British might say ‘confidential’. Whether it should have been so graded is immaterial. Jeanmaire knew it was confidential, knew what he was doing and who for. It may have been a tiny journey, but at that moment he crossed the bridge. In every tale of one man’s path to spying, or to crime, or merely to adultery, there is traditionally one crucial moment that stands out above the rest as the moment of decision from which there is no return. This was Jeanmaire’s. ‘I gave only two pages, not the whole document,’ he says. It seems to have made no difference. A Swiss colonel, as he then was, had voluntarily and without authorization handed a classified document to the Soviet military attaché and resident of the GRU in Bern.

Yet the evening had only begun. Jeanmaire seems to have entered a vortex of reckless generosity. There had been recently a rehearsal of Swiss military mobilization plans. Now Jeanmaire took it into his head to boast to Denissenko that Swiss resistance to a Soviet invasion would be more ferocious than the Kremlin could envisage. He showed Denissenko his personal weapons, including his new semi-automatic rifle. He took him on to the balcony and pointed at the neighbouring houses. He is red-faced and thrilled as he describes this, and that is how I see him on the balcony. ‘If your parachutists jump on to that tennis court, everyone around here will fire at them,’ he warned Denissenko. ‘Forget orders. They won’t wait for them. They’ll shoot.’

He produced the Mobilization Handbook which is issued to every Swiss company commander. He had it by chance at home, he says, in preparation for a lecture he proposed to give in Geneva. Its classification was ‘secret’. The stakes had risen.

Who was pulling now, who pushing? According to Jeanmaire, Denissenko asked to borrow the handbook, promising to return it the next day, so Jeanmaire gave it to him. As if it mattered who was the instigator! ‘Anyway the handbook was common knowledge,’ he adds dismissively. ‘Everyone knew what was in it.’ But that isn’t what the official report has him telling his military examining judge on 23 November 1976: ‘He [Denissenko] vehemently insisted that I give him these documents. Alas, I was weak enough to yield, and I thus put my hand into a trap that I couldn’t get out of. From then on the Russians could blackmail me by threatening to inform my superiors. I told my wife that very day that I had made the blunder of my life.’

But Jeanmaire now denies that he said this.

And Marie-Louise – what did she tell Jeanmaire in return? It seems, almost nothing. Jeanmaire admits that he had an onslaught of guilt after Denissenko left, and confided his anxieties to his wife: ‘And merde, on Monday I’ll go and get the thing back!’ he told her. But Marie-Louise, according to Jeanmaire, merely remarked that what was done was done: ‘She had no sense that anything bad had happened.’

And still on the same crazy evening, Jeanmaire showed Denissenko parts of another classified document on the requisitioning of Swiss property in the event of war – for example, the seizing of civilian transport for the movement of territorial troops. This time he refused to part with it, but made a list of pages relevant to their discussions on ‘dissuasion’. A day or two later, at his office, he made photocopies of these pages under the pretext that they were needed for a study course for air-raid troops. A lie, therefore: a constructive, palpable lie, told to his own people in order to favour his people’s supposed enemy.

Why?

And on the evening of 9 July, he handed the stolen pages to Denissenko. A criminal act. It was on that occasion also that, in the presence of Denissenko, Marie-Louise proudly displayed to her husband a bracelet which she said Denissenko had given her while Jeanmaire was briefly out of the room.

‘When I came back, my wife said, really lovingly: “Look at this beautiful bracelet that Herr Denissenko has given me.” I said “Bravo.” I made nothing of it, except that it was a beautiful gesture by Denissenko. If she’d shown it me without his being there, I might have smelt a rat. Today I know he gave it her at a quite different time. It was a gift of love and had nothing whatever to do with betraying one’s country.’

Denissenko’s gift of love was worth 400 Swiss francs, says Jeanmaire. Referring to it later, he raises its value to 1,200 Swiss frances. Either way, it seems to have been a horribly good bargain in exchange for Jeanmaire’s gift of love to him. The evening ended with another trip to Savigny for a celebratory drink. It is hard to imagine what the three of them thought they were celebrating. With Denissenko’s bracelet glittering proudly on Marie-Louise’s wrist, Jeanmaire had just put a bullet through his muddled soldier’s head.

Marie-Louise Jeanmaire

Why?

Jeanmaire’s prosecutors were not the only ones to hunt for an answer. Jeanmaire himself has had years and years of staring at the wall, asking himself the same question: why? His talk of dissuasion wears thinner the more you listen to it. He speaks of his ‘character weaknesses’. Yet what is weak about a lone crusader setting out to deter the Kremlin from its evil purposes against peace-loving Switzerland? He says the information he passed was common knowledge. Then why pass it? Why in secret? Why steal it, why give it and why be merry afterwards? What was there to celebrate that night? Betrayal? Friendship? Love? Fun? Jeanmaire says Denissenko was a tsarist, an anti-Bolshevik. Then why not report this to his superiors, who might have passed the tip to people with an interest in recruiting a disaffected Russian colonel? Perhaps the answer was simpler, at least for the landlocked Swiss soldier: perhaps it was just change.

For the novelist, as for the counter-intelligence officer, motive concerns the possibilities of character. As big words frequently disguise an absence of conviction, so drastic action can derive from motives which, taken singly, are trivial. I once interrogated a man who had made an heroic escape from East Germany. It turned out that, rather than take his wife with him on his journey, he had shot her dead at point-blank range with a Luger pistol that had belonged to his Nazi father. He was not political; he had no grand notion of escaping to freedom, merely to another life. He had always got on well with his wife. He loved her still. The only explanation he could offer was that his local canoe club had expelled him for antisocial behaviour. In tears, in despair, his life in ruins, a self-confessed murderer, he could find no better excuse.

So again, why?

The more you examine Jeanmaire’s relationship with Denissenko, the more it appears to contain something of the compulsive, the ecstatic and the sexual. Again and again it is Jeanmaire himself, not Denissenko, who is forcing the pace. Jeanmaire needed Denissenko a great deal more than Denissenko needed him: which was probably what gave Denissenko and his masters pause.

After Denissenko’s departure from Bern, it is true, there came a grey troupe of substitute figures – Issaev, Strelbitzki, Davidov. Each, in the longer narrative, presents himself at the door, uses Denissenko’s name, appeals to Jeanmaire’s Russian persona, tightens the screws, finds his way to Jeanmaire’s heart and receives an offering or two to keep the Kremlin happy – or to dissuade it, whichever way you care to read the story. Jeanmaire’s relationship with the GRU is not broken with Denissenko’s departure to Moscow, but neither is it advanced. Were they anti-Bolsheviks too? The fig leaf seems to have been tossed aside: Jeanmaire barely seems to care. For Deni’s sake he gives them scraps; a part of him accepts that he is trapped; another part seems to tell him that his recent translation to the giddy rank of brigadier should somehow exempt him from the unseemly obligation of spying. ‘I thought: Now I’m a brigadier, I’ll pack in this nonsense.’ Yet he continues to enjoy the connection. He dickers like a scared addict, offers them crumbs, warms himself against their fires, fancies himself Switzerland’s secret military ambassador, wriggles, warns them off, calls them back, sweats, changes colour a dozen times, allows himself one more treat, swears abstinence and allows himself another. And the grey, cumbersome executioners of the GRU, knowing the limitations of their quarry, and even perhaps of themselves, make up to him, bully him, flatter him, accept what is to be had, which isn’t much, and show little effort to force him beyond his limits.

Yet it is the figure of Denissenko that glows brightest to the end: Deni who obtained him; Deni who, if charily, baited the trap; Deni who slept with his wife; who was so fine, so well-dressed, so cultivated; Deni with whom it was a joy to be seen in public. All his successors were measured against the original. Some were found wanting. All were reflections of Deni, who remains the first and true love. Deni was noble, Deni was elegant, Deni was of the old school. And Jeanmaire, on his admission, would have slept with Deni if he had been a woman. Instead, Deni slept with Marie-Louise. The desire to please Deni, to earn his respect and approval, to woo and possess him – with gifts, including, perhaps, if it had to be, the gift of his own wife – seems, in the middle years of Jeanmaire’s life, to have seized hold of this affectionate, frustrated, clever, turbulent simpleton like a grand passion, like a fugue.

So it is only natural that Deni, even today in Jeanmaire’s recollection, is a great and good man. For who, when he has wrecked his life for love and paid everything he possesses, is willing to turn round and say: ‘There was nothing there?’

The love of one man for another has had such a dismal press in recent years – particularly where espionage is in the air – that I venture on the subject with hesitation. There is no evidence anywhere in Jeanmaire’s life that he was consciously prey to homosexual feelings, let alone that he indulged them. To the contrary, it is said that after hearing from his defence counsel Jean-Félix Paschoud that his wife had had an affair with Denissenko, Jeanmaire at once wrote her a letter of forgiveness. ‘If they had offered me a pretty Slav girl,’ he is supposed to have written, ‘I don’t know what I might have done.’ The story certainly accords with his known heterosexuality and his self-vaunted hatred of homosexuals, whom he identifies constantly among his former military comrades: X was one and Y was not; Z went both ways but preferred the boys.

In this respect, Jeanmaire is a product of the Swiss military patriarchy. Women, to this Swiss chauvinist, are a support regiment rather than true warriors. Men, as in all armies, are most comfortable together, and sometimes – though not in Jeanmaire’s case – this comfort flowers into physical love. When Jeanmaire speaks of his mother or his wife, he speaks of their loyalty, their good sense, their stoicism, their beauty. He is appalled by the vision of them as victims, for he is their protector. But never once does he speak of them as anything approaching equals.

And when he speaks of his godfather Tissot – the sometimes naked, otherwise superbly uniformed soldier, who, according to Jeanmaire, had to relinquish his command for failing to promote the ‘useful’ people – he recalls as if it were yesterday the terrible moment when he learned that his idol was about to marry a woman he had kept secret for forty years: ‘Tissot had always insisted that soldiering was a celibate vocation. I believed him! I believe him to this day! I was disgusted to observe the two of them embracing. A world collapsed because I had regarded him as absolute. Not that I suspected him of homosexuality, but everyone regarded him as a priest.’

In Denissenko, Jeanmaire seems to have rediscovered the lost dignity of his fallen hero, Tissot, and perhaps in his unconscious mind to have recreated the dashing self-admiring friendship between brothers-at-arms that existed between Tissot and Jeanmaire senior. There is something accomplished, something destined in the way he still speaks of his bond with Denissenko. There is a sense of elevation, of superior knowledge, of: ‘I have been there and I know.’ And something of contempt that adds: ‘And you don’t.’

Jeamaire (on the right) with his godfather Edouard Tissot on a mountain hiking expedition in 1933

Oh, and how the two friends could talk! Between them, the beautiful Russian soldier diplomat and the squat little Swiss brigadier redrew the entire world. They put out their tin soldiers and knocked them down; they fought and played interminably: ‘When we talked politics, I represented democracy and Denissenko dictatorship. Each respected the other’s position perfectly.’

And here it is necessary to dwell – as a defence witness at the trial is said to have done – on the social poverty of Jeanmaire’s life. Good fellowship had been hard to come by until Jeanmaire discovered Bern’s diplomatic community. Partners of the sort he craved were scarce in the ranks of his own kind, and his reputation as a big mouth didn’t help. He found solace in the company of foreign nomads. To them, he brought no baggage from his past. In their company he was reborn.

And finally – if love must have so many reasons – there is the agonizing comedy of Denissenko’s record of real combat. To the Swiss soldier-dreamer who had never heard a shot fired in anger and never would, who had come from a prolonged military tradition of bellicose passivity, the lustre of Denissenko’s armour was irresistible. Not Jeanmaire’s father, not even his godfather Tissot, could match the heroic splendour and the vast authority of a man who had fought at Stalingrad, and whose breast, on military feast days, jangled with the medals of real gallantry and real campaigns. No courtship was too extreme; no risk, no sacrifice, no investment too reckless for such an exalted being. If two souls were warring in Jeanmaire’s breast on that night of his first betrayal – the one thrilling him with words of caution, the other driving him forward along the path of glory – it was the example of his unblooded cavalry forebears that urged him to drive in the spurs and not look back.

One episode, more than any other, reveals to us Jeanmaire’s state of mind during the high days of his honeymoon with Denissenko: it is the bizarre encounter on 30 November 1963 when Denissenko called on Jeanmaire in his apartment in Lausanne and, in a classic pass, tried to fling the net over him for good. According to Jeanmaire the scene unfolded in this way.

Marie-Louise is in the kitchen. Jeanmaire, with his customary ambiguity when speaking of her, no longer remembers whether she is party to the conversation.

Denissenko to Jeanmaire: ‘I told you when we first met that I would like to make reparation to you for the loss suffered by your parents-in-law in Russia.’ Producing a large envelope, unsealed, he holds it out to Jeanmaire. There is money in it. Jeanmaire cannot or will not speculate how much. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of Swiss francs. He remembers hundred-franc notes.

‘It’s a compensation,’ Denissenko explains. ‘As I promised you. A Christmas present.’

Jeanmaire takes the envelope and flings it on the floor. Money flies everywhere. Denissenko is astonished.

‘But it’s not for you!’ Denissenko protests. ‘It’s compensation for the damage done to your parents-in-law.’

‘Then pick it up for yourself,’ Jeanmaire replies. ‘I’m not taking your money.’

The first time Jeanmaire told me this story, he was proud of his behaviour. It should prove, he seemed to think, that he was doing nothing underhand – much as introducing Denissenko and his successors to the proprietors of restaurants should prove there was nothing clandestine about the association. But when I pressed him to explain why he had refused the money – since Denissenko had offered it for such ostensibly honourable reasons, to repair a loss that Marie-Louise had undoubtedly sustained – he altered his ground: ‘I perceived the money at that moment as a bribe. In refusing it, I was admitting inwardly that I had done something impure. I didn’t want anyone to be able to say of me, “He can be had for money.” I never had the feeling that Denissenko wanted to trap me or pump me, but I didn’t want to take his money. It was repellent to me. It had the flavour of a payment for services rendered. I didn’t want him ever to be able to say that I had sold my country – although I knew I wasn’t selling my country or even giving it away for nothing.’

It would be charming to know what Denissenko and his masters in Moscow afterwards made of this bizarre scene and how much sound planning went to waste at the moment when Jeanmaire refused to swallow such a sweetly baited hook. How on earth could the grey men of the GRU be expected to understand that Jeanmaire wanted love, not money?

‘It amazes me that Denissenko could have done it to me,’ says Jeanmaire. ‘After all, he could have given the money to my wife. But probably he wouldn’t do that, because it would have made a whore of her.’

One might suppose that after this uncomfortable scene, the evening would have taken on a sour note. The suitor had made his pitch and been repulsed. Time perhaps to withdraw and fight another day. But not so. True, there were some sticky minutes, but soon the talk brightened and turned to the reorganization of the Swiss Army, which had come into effect on 1 January 1962. Jeanmaire produced a copy of the previous order of battle, valid till 31 December 1961 and therefore out of date: ‘I reckoned that since he was such a good fellow, I would give him something so that he wouldn’t feel useless,’ he explains. And adds that he had been told by Swiss military attachés how grateful they were to be slipped the odd ‘little bit of paper’ to justify their extravagant lifestyle at public expense.

But scarcely is this admission made than he is once more making another: ‘I gave him the order of battle because I’d already put it aside for him when the affair with the money got in the way. But then I gave it to him anyway, to show there were no hard feelings.’

But if the path to Jeanmaire’s mind appears tortuous and paradoxical, it resembles a Roman road when compared with the devious route that led the Swiss authorities to his arrest and trial.

Colonel Vassily Denissenko of the Soviet Embassy in Bern.

Here is the Federal Prosecutor Rudolf Gerber speaking before the Parliamentary Jeanmaire Commission, whose task was to examine the affair and whose report, though widely leaked, is still secret:

On 16 May 1975, we received a warning to the effect that a high-ranking Swiss officer had had significant intelligence contacts with the Russians. The time in question was 1964. It was difficult to work out who it could be. We knew only that the wife of this officer had had relations with Russia during her childhood. Thus we came on Jeanmaire. An investigation was launched in about August 1975.

You don’t have to be a counter-intelligence officer to wonder what on earth was ‘difficult’ about narrowing the field to Jeanmaire on the strength of this information. The number of senior Swiss Army officers whose wives had enjoyed a Russian childhood cannot have been large. Jeanmaire’s contacts with Soviet diplomats in 1964 were a matter of army record. He had been appreciated for them in the military protocol department, where enthusiasts for the official cocktail round were hard to find. He had been deliberately flamboyant in parading them to casual acquaintances.

Where had the tip-off come from? According to the Federal Prosecutor Gerber, only a few initiates know the answer to that question. The intricate game of spy and counter-spy commands his silence, he says: even today, the source is too hot to name. The chief of the Swiss Secret Service at the time, Carl Weidenmann, tells the story differently. From the outset, he says, the only possible suspect was Jeanmaire. He too claims he is not allowed to say why. Apart from such selective nuggets as these, we are obliged to fall back on rumour, and the hardy rumour is that the tip-off came from the CIA.

What did the tip-off say? Did Gerber tell the Parliamentary Jeanmaire Commission the whole or only a part of the information received? Or more than the whole? And if the tip-off did indeed come from the CIA, who tipped off the CIA? Was the source reliable? Was it a plant? Was it Russian? British? French?

West German? Swiss? In the grimy marketplaces where so-called friendly intelligence services do their trading, tip-offs, like money, are laundered in all sorts of ways. They can be slanted, doctored and invented. They can be blown up so as to cause consternation or tempered to encourage complacency. They serve the giver as much as the receiver, and the receiver sometimes not at all. They come without provenance and without instructions on the package. They can wreck lives and careers by design or by accident. And the one thing they have in common is that they are never what they seem.

In Jeanmaire’s case, the provenance and content of the original tip-off are of crucial importance. And until today, of crucial obscurity.

Kurt Furgler, the Federal Minister of Justice (on the right), and Rudolf Gnägi, the Federal President, on 9 November 1976.

After the tip-off – a full three months after it, and fourteen years after Jeanmaire’s first meeting with Denissenko – came the grand-slam secret surveillance, like a thunder of cavalry after the battle has been lost. Jeanmaire’s telephone was tapped; he was watched round the clock. He was probably also microphoned, but Western surveillance services have a uniform squeamishness about owning up to microphones. A ranking police officer claims to have disguised himself as a waiter at diplomatic receptions attended by Jeanmaire: ‘I heard only trivial party gossip,’ he told Jeanmaire after his arrest. ‘Soldiers’ chatter about music, alcohol and women.’ Again the police officer speaks as if he was wired.

And after four months of this, the watchers still had nothing against Jeanmaire except the tip-off, and what was vaguely perceived, in Gerber’s words, as ‘contacts with Russians in excess of the customary level’. But what was the normal level, given Jeanmaire’s celebrated predeliction for Russian contacts for which the army’s protocol department gave him humble thanks? By December, the watchers were worried that Jeanmaire’s imminent retirement would fall due before they had a case against him. Therefore Weidenmann, the Chief of the Secret Service, in collaboration with the Chief of Federal Police and the Federal Prosecutor, decided to offer Jeanmaire employment that would keep him in harness. To this end Weidenmann summoned Jeanmaire to an interview.

‘It would be a pity,’ he told Jeanmaire, ‘to let you leave the army without first committing to paper your knowledge and experience in the field of civil defence.’

For an extra 1,000 francs a month – later, in a fit of bureaucratic frugality, dropped to 500 francs – Weidenmann proposed that the pensioner Jeanmaire undertake a comparative study of military and civil defence in all countries where the Swiss maintained military attachés. Jeanmaire was flattered, and the investigators had bought themselves more time.

‘I suspected nothing,’ says Jeanmaire.

On 13 January, Weidenmann summoned Jeanmaire to him again and, in an effort to prod him into a betrayal, arranged for him to have access, through chosen intermediaries, to secret documents in the possession of Switzerland’s overseas intelligence service. Weidenmann testified later that his department took care to ensure that Jeanmaire didn’t get his hands on anything hot. The intermediaries, of course, were party to the provocation plan.

As a further inducement to Jeanmaire, a small office was set up for him in no less a shrine than the headquarters of Colonel Albert Bachmann, who ran his own special service, known in Swiss circles as the ‘Organization Bachmann’, and for long the object of much wild rumour and public agonizing, most notably after a ludicrous episode in which one of its agents had been caught spying on Austrian (sic) military manoeuvres. Bachmann was also charged with responsibility for Switzerland’s ‘Secret Army’, which would form the nucleus of an underground resistance group in the event of Switzerland being occupied by hostile forces. No Soviet spy or intelligence officer worth his salt, it was reasoned, could resist such an enticing target as the Organization Bachmann. The office was bugged all ways up, Jeanmaire’s phone was tapped and Bachmann was duly added to the team of watchers. But alas the hen still refused to lay.

Chief of the Secret Service Weidenmann before the Parliamentary Jeanmaire Commission: ‘He was kept under observation during this period, unfortunately without success.’

After another eight months of frustration, during which Jeanmaire’s every word and action were laboriously studied by his watchers, Federal Prosecutor Gerber decided to arrest him anyway, despite the fact that, on Gerber’s own admission, he lacked the smallest scrap of hard evidence.

But Gerber and his associates had something on their minds that weighed more heavily than legal niceties and cast a shadow over their professional existence. The American intelligence barons had recently served formal notice on Bern that Washington had no confidence in the ability of the Swiss to protect the military secrets entrusted to them. Vital technical information about American armaments was finding its way from Switzerland to Eastern Europe, they said. The Florida early-warning-system had been compromised. So had state-of-the-art American electronic equipment fitted to Swiss tanks, most notably the ‘stabilizor’. It was also rumoured that the Americans were refusing to sell Switzerland their new 109 artillery pieces and, worse still, threatening to relegate Switzerland to the status of a Communist country for the purposes of secrets-sharing, a humiliation that rang like a panic bell in the proud back rooms of Switzerland’s intelligence and procurement services.

Never mind that Jeanmaire had not been admitted to such secrets. Never mind that he was not qualified in the technology allegedly betrayed, or that the army had chosen to confine him to a harmless backwater without a secret worth a damn. There was the leak, there was the threat, there was the tip-off, there was the man. What was now needed, and quickly, was to put the four together, silence American apprehensions and re-establish Switzerland’s self-image as a responsible and efficient military (and neutral) power.

One of Jeanmaire’s principal interrogators, who also arrested him, was Inspector Louis Pilliard, Commissioner of the Federal Police – the same officer who claimed to have dressed as a waiter to spy on Jeanmaire at diplomatic functions. During Jeanmaire’s days of ‘examination arrest’ – that is to say, in the days before he was even brought before a military examining judge – Pilliard, the civilian policeman, questioned him, according to Jeanmaire’s secret notes made on scraps of paper, for a total of ninety-two hours. Forget the European Convention on Human Rights, to which Switzerland is a signatory and which requires a prisoner to be brought before a judge in swift order: Jeanmaire had already served 107 days in isolation and had another six months to go before his trial.

‘You have betrayed Florida,’ Pilliard told him at the end of October.

‘You’re mad,’ Jeanmaire replied. ‘I can prove to you that I don’t know the first thing about Florida.’

Albert Bachmann of ‘Organization Bachmann’

And indeed, on the one occasion in 1972 when Jeanmaire could have attended a demonstration of the Florida early-warning-system, he had sent a letter declining the invitation, which Pilliard to his credit traced. But if the charge of betraying Florida was now struck out, Jeanmaire remained in the eyes of his public accusers – and of Justice Minister Furgler – a spy of monstrous dimensions. Finally, on 10 November, Parliament ruled that all derelictions by Jeanmaire and his wife should be tried by military justice.

For Marie-Louise was also charged. While her husband was being bundled into a police car on his way to work, five federal police officers, one a woman, had descended on the Jeanmaire flat in the Avenue du Tribunal-Fédéral in Lausanne at seven in the morning to conduct a house-search, which lasted two days. Their finds included Marie-Louise’s diary, where she had recorded all meetings with Denissenko, and a television set of unspecified origin, but probably given to the Jeanmaires by Issaev, one of Denissenko’s successors. The diary has since disappeared into the vaults of Swiss secrecy, but it is said by Jeanmaire – who helped to decode it – to contain an entry that reads: ‘Today Deni and I made love.’

The police also descended on Jeanmaire’s friend and neighbour in Bern, Fräulein Vreni Ogg, at her place of work at the Bern office for footpaths. Having seized her, they bundled her too into a car, drove her to a police station and released her half an hour later, having apparently decided she had nothing worthwhile to tell them. The media had another treat and her life was never the same.

Jean-Louis and Marie-Louise Jeanmaire during the winter of 1975-76.

Soon Jeanmaire was singing like a bird, but not the song his questioners wished to hear.

Federal Prosecutor Gerber again, before the Parliamentary Jeanmaire Commission, in a lament that should be pasted to the wall of every hall of justice in the free world: ‘The nub of the thing is this: in Switzerland we do not have the means to increase Jeanmaire’s willingness to testify.’ After lightning arrest, solitary confinement, deprivation of exercise, radio, newspapers and outside contacts; exhaustive interrogation; threats and blandishments – what other means was Gerber thinking of, we wonder?

Jeanmaire was interrogated principally by Pilliard, who was sometimes accompanied by another officer, one Lugon, Inspector of the Waadtland Canton Police. Like Pilliard, Lugon had taken part in Jeanmaire’s arrest. 1 But others, including Gerber himself, had their turn at the interrogation – Gerber for four full hours, though the content of their discussion escapes Jeanmaire’s recollection: ‘He shook my hand. He was decent. I told him I was relieved to be interrogated by someone of authority. My memory is kaputt…’

It is kaputt, perhaps, because it was on this occasion – 8 September, according to Gerber’s testimony – that Gerber read out to Jeanmaire the list of the confessions he had by now made and which later constituted the bulk of the case against him. It is kaputt because a part of Jeanmaire’s head knows that, within a month of his arrest and probably less, he had confessed away his life.

Nevertheless, the interrogation seems to have been conducted with a signal lack of skill. Jeanmaire, after all, was an interrogator’s dream. He was terrified, disoriented, indignant, friendless and guilty. He was then, and is today, a compulsive, non-stop prattler, a braggart, a child waiting to be enchanted. What was needed in his interrogator was not a bully but a befriender, a confessor, someone who could interpret his dilemma to him and receive his confidences in return. Forget your lynx-eyed intelligence officer, master of five languages: one wise policeman with a good face and patient ear could have had him on a plate in a week. No such figure featured in the cast.