On 1 December 1989, Granta asked a number of writers how they understood the events in Central and Eastern Europe. Change had come at an incomprehensible speed: the re-burying of Imre Nagy in Hungary, the opening of the borders there, the elections in Poland, the trains of immigrants into Germany, the resignation of Erich Honecker. It seemed impossible that change could come any faster, but it did, and in November events seemed to accelerate: on 9 November, the Berlin Wall; sixteen days later, the resignation of Ladislav Adamec, the Czechoslovak prime minister. So many things in Europe would never, could never, be the same. Was is possible to record this particular moment, poised, as we felt we were at the beginning of December, between two histories: the one before 9 November, and that other one, still to be defined, already being debated, which we knew we were then entering?

This is what we asked of our writers. But, even in this, our judgement of the moment was premature. By the time the fifteen writers had received our letter (the weekend, it turned out, that Gorbachev and Bush were meeting in the Mediterranean), Erich Honecker was placed under house arrest; and by the time we received their answers Gustav Husák had resigned in Czechoslovakia. The week before Christmas, the last contribution to our forum arrived; it was written by the Romanian poet Mircea Dinescu, but it could not have been mailed by him. Since May, he had been under house arrest, under the surveillance, it is reported of eighteen security officers. The day we received his translation, we also received the first reports from Timasoara in Romania. There were no Western journalists there; we have only unconfirmed reports of indiscriminate killings – the number of deaths being mentioned is terrible to contemplate. Dinescu’s contribution – what should it be called? an essay? a polemic? a cry for help? – is a reminder of the utter and insistent and implacable seriousness of the issues underlying this debate.

Josef Škvorecký

These are days of understandable, and I hope not premature, jubilation in Czechoslovakia. The generation of twenty-year-olds who were bloodied by the police and went on to topple the power monopoly of the Communist Party, are experiencing pure bliss untainted by any – even tiny – drops of sadness. That’s how it should be because it’s natural. The twenty-year-olds have lost nothing yet, and only conditions of extreme severity can deprive a person of the happiness, eagerness and excitement that is youth. Difficulties, harassments, attempts to curb their freedom appear to young people as adventures, of which the regime has provided them with plenty, particularly in its lunatic campaigns against their favourite music. In these crusades the youngsters turned victorious, years before the present triumph. Nothing mars their euphoria now.

As one turns to the generation of their parents, now in their early forties, the picture changes. Two decades ago, when they were twenty themselves, this generation was as euphoric as their sons and daughters are today. But the Big Lie descended on Czechoslovakia and those who were starting adult life in 1968 lost their most creative, and potentially happiest, years to the abomination called Realsozialismus. There is sadness in their elation, but they still have a good reason to rejoice: at forty, one may still begin anew, and almost half of life lies ahead.

For the grandmothers and grandfathers, now in their sixties, the sadness changes to bitterness. They are the generation of the uranium mines, of the show trials, of the petty chicanery of security screenings; the closely watched generation for whom admission to universities was determined not by talent but by political reliability. Too many were never able to achieve what, at twenty, when life was hope and eagerness, they had thought they would. At sixty it’s too late.

Of course everybody is glad that the bell tolls for the oppressive regimes that have been deforming human lives in Czechoslovakia since 1939 – if this is indeed their definitive end. But those who have lived there cannot be blissfully unaware of what happened on the totalitarian ‘road to socialism’. That road is literally paved with human skulls. Where did it lead? To the social security of the jail? In many lands it led not even to that, but rather to a society resembling a concentration camp.

It all appears to be a huge joke played on mankind by history. The joke, however, is ebony black.

The days of the totalitarians may be numbered in most of Europe. Elsewhere they evidently are not; in some places they are just beginning. At universities in the West professors still preach the theory which was the backbone of the longer-lasting of the two deadening social experiments in our century. But Marx was right on one point: the only criterion of a theory’s validity is the test of practice.

Let us rejoice by all means. I don’t want to spoil the celebration. It’s just that I’ve never been good at euphoria and I cannot purge my mind of some thoughts.

Sorry.

George Steiner

I am writing this note on 5 December 1989. It may be absurdly dated by the time it appears.

This is an obvious point. The speed of events in Eastern Europe, the hectic complexities of inward collapse and realignment are such as to make the morning papers obsolete before evening. There may have been comparable accelarandos before this: in France, from June to September 1789 (there is a haunting leap from that date to ours); or during those ‘ten days that shook the world’ in Lenin’s Petrograd. But geographical scale of the current earthquake, its ideological and ethnic diversity, the planetary interests which are implicated, do make it almost impossible to respond sensibly, let alone have any worthwhile foresight.

A touch of exultant irony is allowed in the face, precisely, of this triumph of the unexpected. No economist-pundit, no geopolitical strategist, no ‘Kremlinologist’ or socio-economic analyst foresaw what we are living through. There was, indeed, all manner of speculation on the decay of institutions and distributive means in the Soviet Union. Some sort of challenge in Poland was on the cards. But all the pretentious jargon, the econometric projection charts, the formalistic studies of international relations, have proved fatuous. We are back with Plutarch. The apocalypse of hope has been started by one man.

Historians will generate volumes of hindsight, sociologists and economists will juggle determinants and predictable certainties. Eyewash. The fact is that we know next to nothing of the intuitive panic, the alarmed vision, the gambler’s stab into the unknown which may or may not have brought on Gorbachev’s hoisting of the old, sclerotic but certainly defensible order. If Plutarch won’t do, we are back to the miraculous, to the tears of the Black Virgin over Poland, to the incensed saints and patriarchs who have taken to heart the long strangulation of Hungary, of Bulgaria. We are back to the enigmatic pulse-beat of the messianic.

Second gloss: the cardinal ambiguity in the role of the United States. That role is now almost surrealistically irrelevant. Bush bobbing on the waves of Malta is an apt picture. The US appears to be bobbing a provincial colossus, ignorant of, indifferent towards Europe. It will have its heavy hands full with Latin and Central America, with the derisive patronage of Japan. Europe is again on its own.

On the other hand, the image, the ‘symbol-news’ of America has been decisive. The millions who poured westward through the broken Berlin Wall, the young of Budapest, Sofia, Prague or Moscow, are not inebriate with some abstract passion for freedom, for social justice, for the flowering of culture. It is a TV-revolution we are witnessing, a rush towards the ‘California-promise’ that America has offered to the common man of the tired earth. American standards of dress, nourishment, locomotion, entertainment, housing are today the concrete utopia in revolutions. With Dallas being viewed east of the Wall, the dismemberment of the regime may have become inevitable. Video-cassettes, porno-cassettes, American-style cosmetics and fast foods, not editions of Mill, de Tocqueville or Solzhenitsyn, were prizes snatched from every West Berlin shelf by the liberated. The new temples to liberty (the 1789 dream) will be McDonald’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken.

Hence the paradox: as the US declines into its own ‘pursuit of happiness’, the packaged promise, the bright afterglow of that pursuit becomes essential in Eastern Europe and, very probably, in the post medieval, Asiatic morass of the Soviet Union.

Everything can still go wrong. Gorbachev’s survival seems to hang by a thread. Clearly, the old guard on the right is desperate, the new radicals on the left are crazily impatient. Slovak indifference chills the new Prague Spring. Can the lunatic and sadistic self-destruction of Romania be halted? What will happen if Yugoslavia splits? Not only in Peking are there large squares ideal for tanks. One prays and hopes and rejoices and rages at the tepid bureaucracies of the Common Market and the prim neo-isolationism of Thatcherite Britain. Everywhere, we are witnessing an almost mad race between resurgent nationalism, ethnic hatreds and the counter-force of potential prosperity and free exchange.

The variant on Judaic-messianic idealism, on the prophetic vision of a kingdom of justice on earth, which we call Marxism, brought intolerable bestiality, suffering and practical failure to hundreds of millions of men and women. The lifting of that yoke is cause for utter gratitude and relief. But the source of the hideous misprision is not ignoble (as was that of Nazi racism): it lies in a terrible overestimate of man’s capacities for altruism, for purity, for intellectual-philosophic sustenance. The theatres in East Berlin performed the classics when heavy metal and American musicals were wanted. The bookstores displayed Lessing and Goethe and Tolstoy, but Archer and Collins were dreamed of. The present collapse of Marxist-Leninist despotisms marks the vengeful termination of a compliment to man – probably illusory – but positive none the less.

What will step into the turbulent vacuum? Fundamentalist religion is clawing at our doors. And money shouts at us. The West inhabits a money-crazed amusement arcade. The scientific-technological pinball machines ring and glitter brilliantly. But the imperatives of privacy, of autonomous imagining, of tact and spirit and scruple in the face of non-utilitarian values, are dimmed. And we lay waste the natural world. Only an autistic mandarin would deny to the mass of his fellow men and women the improved living standards, the bread and circuses we are now fighting, emigrating or dreaming towards. But if one is possessed of the cancer of thought, of art, of utopian speculation, the shadows at the heart of the carnival are equally present.

The knout on the one hand; the cheeseburger on the other. The Gulag of the old East, the insertion of pantyhose ads between gas-oven sequences of Holocaust on TV in the new West. That alternative must be proved false if man is to be man. Will the breaking of the walls be proved false if man is to be man? Will the breaking of the walls make the choices more fruitful and meaningful, more attuned to human potential and limitation? Only a fool would prophesy.

P.S. 11 December. Events have in fact, accelerated during the past six days. The Prague secret police are now headed by a man who was their prisoner less than four weeks ago. There is no East German government. Bulgaria is swinging towards a multi-party scheme. The Baltic republics are defying Moscow.

I can make more precise the notion of the Marxist overestimate of man. It was Moses’s error all over again (remember his desperate rages and death short of the promised land), and Christ’s illusion. As that error, and its savage cost, are once again made plain and amended, will Jew-hatred, in the persistent eschatological sense, smoulder into heat? Already there are ugly signals from Hungary and East Germany.

Jurek Becker

Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann

‘Really existing socialism’ is on the way out, no question. Good thing too, if you fix your mind on the true condition of life in the socialist states, and not the fictional version which their leaders have passed off as the truth. The West has won – and there’s the rub.

Here in the West, we live in societies that have no particular goal or objective. If there is any guiding principle, it’s consumerism. In theory, we can increase our consumption until the planet lies about us in ruins and, given current trends, that’s precisely what will happen. In spite of everything we knew and understood about them, we had a hope that the socialist states might find a different path. That hope is gone. People there are desperate to adopt the principles of the West: the conversion of as many goods as possible into rubbish (which is what consumption means), and the free expression of all types of ideas (accompanied by a growing reluctance to think at all). Converts are liable to be especially strict and zealous in the observance of their new faith; I expect the same will apply to the people of these recently converted nations.

A few days ago, I was talking to a friend about the possibility of German reunification, the conversation that all Germans have been having these past days and weeks. He was in favour of it, I was against. After a while he lost his temper with me, and asked me how I could possibly justify the continued existence of the German Democratic Republic. I started thinking, and I’m still thinking now. If I can’t think of any reasons, I shall have to change my mind and become a supporter of reunification. I shall have to be in favour of turning Eastern Europe into an extension of Western Europe.

The only argument I am able to come up with is perhaps more suitable for a poem than a political discussion: the most important thing about socialist states isn’t any tangible achievements, but the fact that they give us a chance. Things are not cut and dried as they are here. The uncertainty there doesn’t promise anything, of course, but it’s our only hope for the continued existence of humanity. Eastern Europe looks to me like one last attempt. And when it’s over, it’ll be time to withdraw our money from the bank, and start hitting the bottle in earnest.

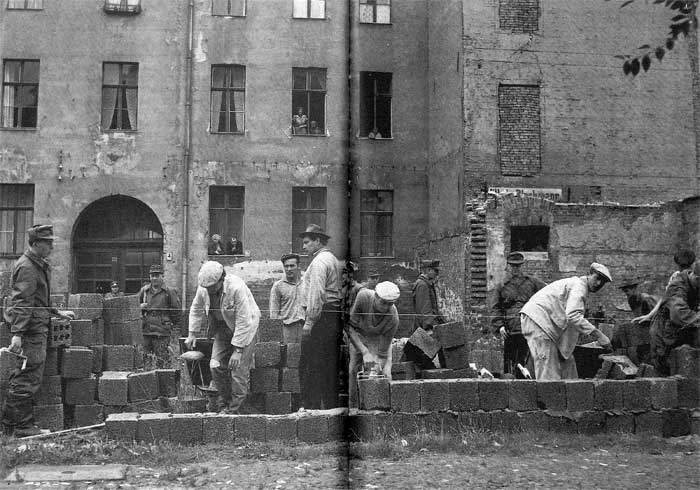

Building the Berlin Wall, 1961

Hans Magnus Enzensberger

Translated from the German by Piers Spence

You find them in every European capital, in the centre of the city, where space is symbolic: corpulent centaurs, metal hermaphrodites, Roman emperors, grand dukes, eternally victorious generals. Under their hoofs, civil servants hurry to their ministries, or spectators into the opera, or believers to Mass. They represent the European hero, without whom the history of the continent is barely imaginable. But with the invention of the motor car, the spirit of the age dismounted – Lenin and Mussolini, Franco and Stalin, all managed without a whinnying undercarriage and the stockpiles of heroes in stone were shipped off to Caribbean islands or Siberian combines. Inflation and elephantiasis heralded the end of the hero whose principal preoccupations were conquest, triumph and delusions of grandeur.

Writers saw it coming. A hundred years ago literature waved goodbye to those larger-than-life characters whose very creation it had helped bring about. The victory song and the tales of derring-do belong now to prehistory. No one is interested in Augustus or Alexander; it is Bouvard and Pecuchet or Vladimir and Estragon. Frederick the Great and Napoleon have been relegated to the literary basement; as for those Hymns to Hitler and Odes to Stalin – they were destined for the scrap heap from the very start.

In the past few decades, a more significant protagonist has stepped forward: a hero of a new kind, representing not victory, conquest and triumph, but renunciation, reduction and dismantling. We have every reason to concern ourselves with these specialists in denial, for our continent depends on them if it is to survive.

It was Clausewitz, the doyen of strategic thinking, who showed that retreat is the most difficult of all operations. That applies in politics as well. The non plus ultra in the art of the possible consists of withdrawing from an untenable position. But if the stature of the hero is proportional to the difficulty of the task before him, then it follows that our concept of the heroic needs not only to be revised, but to be stood on its head. Any cretin can throw a bomb. It is 1,000 times more difficult to defuse one.

Popular opinion, especially in Germany, holds to the traditional view. It demands steadfastness of purpose, insisting on a political morality which places single-mindedness and adherence to principle above all else, even, if it comes to it, above respect for human life. This unambiguity is not on offer from the heroes of retreat. Retreating from a position you have held involves not only surrendering the middle ground, but also giving up a part of yourself. Such a move cannot succeed without a separation of character and role. The expert dismantler shows his political mettle by taking this ambiguity on to himself.

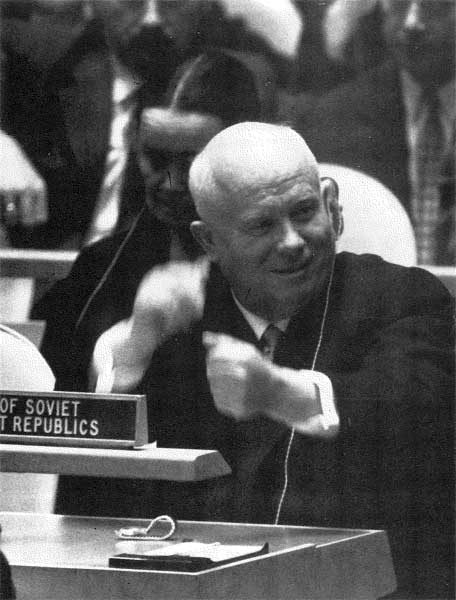

The paradigm is particularly apparent in the wake of this century’s totalitarian dictatorships. At first the significance of the pioneers of retreat was barely detectable. People still claim that Nikita Khrushchev didn’t know what he was doing, that he couldn’t have guessed the implications of his actions; after all, he talked of perfecting Communism, not of abolishing it. And yet, in his famous speech to the Twentieth Party Congress, he sowed more than the seeds of his own downfall. His intellectual horizons may have been narrow; his strategy clumsy and his manner arrogant, but he showed more courage in his own beliefs than almost any other politician of his generation. It was precisely the unsteady side to his character that suited him for his task. Today the subversive logic of his credentials as a hero lie open for all to see: the deconstruction of the Soviet empire began with him.

The internal contradictions of the historical demolition man were more starkly exposed in the career of János Kádár. This man who, a few months ago, was buried quietly and unobtrusively in Budapest, made a pact with the occupying forces after the failed uprising of 1956. It is rumoured that he was responsible for 800 death sentences. Hardly had the victims of his repression been buried than he got to work on the task that was to occupy him for the next thirty years: the patient undermining of the absolute dictatorship of the Communist Party. It is surprising that there was no serious disturbance; there were constant setbacks and shattered hopes, but through compromise and tactical manoeuvring, Kádár’s process moved inexorably forward. Without the Hungarian precedent it is hard to see how the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc would have begun; Kádár’s trailblazing role in this is beyond dispute. It is equally clear that he was no match for the forces he helped to unleash. His was the archetypal fate of the historical demolition man: in doing his job he ended up undermining his own position. The dynamic he set in motion hurled him aside, and he was buried by his own successes.

Adolfo Suarez, general secretary of the Spanish phalange, became prime minister after Franco’s death. In a meticulously planned coup he did away with the regime, installed his own Unity Party in power and forced through a democratic constitution; the operation was delicate and dangerous. This was no vague hunch, like Khrushchev’s; this was the work of an intelligence at the height of its awareness: a military putsch would have led to bloody repression and perhaps a new civil war.

This course of action again is inconceivable from someone unable to differentiate beyond black sheep and white sheep. Suarez played a role in and gained advantage from the Franco regime. Had he not belonged to the innermost circles of power he would not have been in a position to abolish the dictatorship. At the same time, his past earned him the undying mistrust of all democrats. Indeed, Spain has not forgiven him to this day. In the eyes of his former comrades he was a traitor; those whose path he had cleared saw him as an opportunist. After abdicating his leading role in the period of transition he never found his feet again. His role in the party system of the republic has remained obscure. The hero of retreat can only be sure of one thing: the ingratitude of the fatherland.

The moral dilemma assumes almost tragic dimensions in the figure of Wojciech Jaruzelski. In 1981, he saved Poland from the inevitability of Soviet invasion. The price of salvation was the introduction of martial law and the internment of those very members of the unofficial opposition who today run the country under his presidency. The resounding success of his policies did not spare him the wrath of the Polish people, a large number of whom regard him to this day with utter hatred. No one cheers him; he will never escape the ghost of his past actions. Yet his moral strength lies in the fact that he knew from the very beginning that this is how it would turn out. No one has ever seen him smile. With his stiff, lifeless gestures and his eyes hidden behind dark sunglasses he personifies the patriot as martyr. This political Saint Sebastian is a figure of Shakespearean stature.

Nikita Khruschev, September 1960

The same cannot be said of those who lagged behind him. Egon Krenz and Ladislav Adamec will in all probability merit only a footnote in history, the one as a burlesque, the other a petty bourgeois version of the heroic rearguard. But neither the grin of the German nor the fatherly countenance of the Czech should be allowed to obscure the importance of the part they played. The very agility we reproach them for has been their only service. In that paralyzing stillness of the pregnant moment, when one side waits for the other to move and nothing happens, someone had to be the first to clear his throat, to utter the first half-choked whisper that started the avalanche. ‘Someone,’ a German social democrat once said, ‘has to be the bloodhound.’ Seventy years later someone had to spike the bloodhounds’ guns, although as it turned out it was a Communist Pulcinella who broke the deadly silence. No one will cherish his memory. This in itself makes him memorable.

The real hero of deconstruction, however, is himself the driving force. Mikhail Gorbachev is the initiator of a process with which other, willingly or unwillingly, can only struggle to keep up. His is – of this we can probably now be certain – a timeless figure. The sheer size of the task he has taken on is without precedent. He is attempting to dismantle the second to the last remaining monolithic empire of the twentieth century without the use of force, without panic, in peace. Whether he can succeed remains to be seen; he has already achieved what no one, even a few months ago, would have believed possible. It took long enough before the rest of the world began to understand what he was doing. The superior intelligence, the moral boldness, the far-reaching perspective of the man lay so far outside the horizons of the political elite, East and West, that no government dared take him at his word.

Gorbachev has no illusions about his popularity at home. The greatest proponent of the politics of doing without is confronted at every step with demands for something positive, as if it were enough simply to promise the people another golden future where everyone would receive free soap, rockets and brotherly affection, each according to his needs; as if there were any other way forward but by retreating; as if there were any other hope for the future but by disarming the leviathan and searching for a way out of the nightmare and back to normality. It goes without saying that the protagonist risks his life with every step he takes on this path. He is surrounded on the right and on the left by enemies old and new, loud and silent. As befits the hero, Mikhail Gorbachev is a very lonely man.

Not that we should lionize these greater and lesser heroes of deconstruction; they are not asking for that. Any memorial would be superfluous. It is time, however, to take them seriously, to look more closely at what they have in common and how they differ. A political morality which recognizes only good and evil spirits will not be up to this task.

General Wojciech Jaruzelski, December 1982

A German philosopher once said that by the end of the century the question would no longer be one of improving the world but of saving it, which applies not only to those dictatorships whose elaborate dismantling we have watched with our own eyes. The Western democracies are also facing an unprecedented dissolution. The military aspect is only one of many. We must also withdraw from our untenable position in the war of debt against the Third World, and the most difficult retreat of all will be in the war against the biosphere, which we have been waging since the industrial revolution. It is time for our own diminutive statesmen to measure up to the demolition experts. An energy or transport policy worthy of the name will only come about through a strategic retreat. Certain large industries – ultimately no less threatening than one-party rule – will have to be broken up. The courage and conviction necessary to bring this about will hardly be greater than those the Communist functionary had to summon up to do away with his party’s monopoly.

But instead our political leadership senses victory, indulging in ridiculous posturing and self-satisfied lies. It gloats and it stonewalls, thinking it can master the future by sitting it out. It hasn’t the slightest idea about the moral imperative of sacrifice. It knows nothing of the politics of retreat. It has a lot to learn.

Werner Krätschell

Translated from the German by Martin Chalmers

I think of three moments.

The first is on a Sunday, 13 August 1961: Lake Mälar in Sweden. One of the best summers of my life. I am in Finland with Albert, my favourite among eight brothers and sisters – he is twenty and I am twenty-one. We have left our parents’ home in East Berlin and have set out ‘illegally’: we didn’t get permission for our journey and so have committed a criminal offence. We flew from West Berlin to Hamburg, where we got West German passports, and continued our journey northwards, to the land of our dreams, as citizens of the Federal Republic.

Monday, 14 August 1961: The very next day the manager of the estate where we’re staying comes rushing into the kitchen. We are eating breakfast, and he is shouting: ‘It’s all over, boys. You can’t go back again. They’ve closed the borders.’ He shows us the newspapers and the photos are upsetting.

In the evening we sit by the stove in our little guesthouse. It is built out over the lake and was once used by the washerwomen for their hard work. We have a decision to make. Albert wants to stay. He is about to get his school diploma in West Berlin. I want to go back. I am studying theology and don’t want to stop. Following an old family tradition, I want to become a minister, a minister ‘in the East’. Every generation of our family has had one: I want to return to the parsonage, where, apart from my youngest sister, only my parents now remain. Mother has multiple sclerosis. That, too, is a reason.

9 November 1989: In the evening, in the historic Friedrichstadt French church, I preside over one of the many recent and remarkable political meetings. I am joined by Manfred Stolpe, one of the leaders of the Protestant Church, and Lothar de Maizière, who, tomorrow, will be elected chairman of the Christian Democrats. All the guilty political parties have sent representatives to our meeting; we are witnessing a palace revolt amid members of this previously colourless, cowardly, corrupt party. The Communist, Professor Döhle, speaks first. There is – because of the poor acoustics – laughter and spontaneous applause as I lead him to the front. For the first time in his life he now stands – irritated but happy – in a pulpit, with ecclesiastical permission, in the middle of the camp of the old ‘class enemy’, the Church. What an image, what emotion! Is it a foretaste of the night to come?

On leaving the church, a French journalist tells me a strange piece of news: Schabowski, the Communist Party boss in Berlin, and Egon Krenz, have hinted at the possibility that the border might be opened. I waste no time and drive quickly to Pankow. As I pass the Gethsemane church on Schönhauser Allee, I see images of the violence that occurred at the beginning of last month: once again, I see the police, the army, the ‘Stasi’ men, the armoured vehicles and shadowy figures wielding batons. I reach our home and find Konstanze, my twenty-year-old daughter and her friend Astrid, who is twenty-one. Rapidly we jump into the car and drive at great speed to the nearest border crossing: Bornholmer Strasse.

Dream and reality become confused. The guards let us through: the girls cry. They cling together tightly on the back seat, as if they’re expecting an air raid. We are crossing the strip that for twenty-eight years has been a death zone. And suddenly we see West Berliners. They wave, cheer, shout. I drive down Osloer Strasse to my old school where I got my diploma in 1960. We don’t stay long, however, and must return right away because there are still two younger children sleeping at home, and because Astrid is pregnant, and because I have to fly to London early in the morning. But, when we turn around, we see that we are not going to get through. We were among the very first to cross the border. Now the news has spread like wildfire. Hundreds, thousands block our way. There are people who recognize me and they pull open the car door: kisses and tears and we are all in a trance. Astrid, suddenly, tells me to stop the car at the next intersection. She wants only to put her foot down on the street just once. Touching the ground. Armstrong after the moon landing. She has never been in the West before.

All around us, people are beating their fists on my car with joy. The dents will remain, souvenirs of that night.

I hardly sleep and in the morning pass ‘normally’ through the Friedrichstrasse crossing point. Hundreds crowd through the narrow doors, which were, until yesterday, the ‘gates of inhumanity’. My son Joachim stands on the other side. His ‘summer at Lake Mälar’ was in Hungary and was called ‘Balaton’. There, also in August, he made his decision to leave his country and his parents’ home. He was without hope. In May and June, he had demonstrated against both the rigging of the elections that had taken place earlier this year and the bloody suppression of the popular movement in China. The consequences were unpleasant. He attempted to escape, and, on his first attempt, he was caught by the Hungarian soldiers. He tried again, and, on his second attempt, he ran for his life. Now he’s here. Weeks of pain – for him and for us – are over. His brother Johannes (thirteen) and sister Karoline (seven) don’t yet understand the new possibilities. In August Joachim was still twenty-one. His decision was different from mine. Or was it just the same?

The twenty-eight years between: Not until I am on the plane on my way to London and I am alone, alone for the first time after all these dramatic weeks. What have these twenty-eight years meant to you?

Back then, at Lake Mälar in Sweden, I could not imagine that I would one day be married or that I would one day have children. Have they suffered? Yes: there have been hardships; no: there has been inner wealth. They grew up in a parsonage, where the beggar was as welcome as the diplomat, the worker as welcome as the poet. They have had music and Christmas, the landscape of the Mark Brandenburg and good friends. The friends came from the East and West and brought reports and thoughts which saved us from being provincial. And conversation: dense and full of passion. The way we were in those conversations, that’s how we really were.

We lived in that other world made wretched by the Communists. We have known the broken and the damned and the ones deprived of their citizen rights. I am only realizing now how, for twenty-eight years, I got caught up again and again by their stories and by the need, therefore, to help them. So many times it had been necessary to get people ‘to the West’ – very often by difficult routes. They didn’t want to live here, or they couldn’t live here, or they weren’t allowed to live here anymore – it was always a question of life. But it was also necessary to protect the people who wanted or had to stay here, and who had fought back against the system of repression with their own small strength. I think of the groups that gathered in our churches and community centres since the beginning of the eighties, made up of people who were discovering, without knowing it, the principle of non-violence, who were discovering as well that it was a political instrument, one that they then developed in themselves and for others, so that it became the hallmark of the changes.

What I can hear now, here and from the movements in Eastern Europe, is not only a cry for freedom and human dignity; I also hear an urgent plea to the community of Western Europe not to forget us. We want to be part of things when, in 1992, the Western European Community makes the leap into a better life. We don’t want to become Europe’s ‘Third World’. I desire an end to the German as well as to the European division, in which the human dignity of the East Germans and the East Europeans is not damaged, but strengthened.

Isaiah Berlin

You ask me for a response to the events in Europe. I have nothing new to say: my reactions are similar to those of virtually everyone I know, or know of – astonishment, exhilaration, happiness. When men and women imprisoned for a long time by oppressive and brutal regimes are able to break free, at any rate from some of their chains, and after many years know even the beginnings of genuine freedom, how can anyone with the smallest spark of human feeling not be profoundly moved? One can only add, as Madame Bonaparte said when congratulated on the historically unique distinction of being mother to an emperor, three kings and a queen, ‘Qui, pourvu que ça dure.’ If only we could be sure that there will not be a relapse, particularly in the Soviet Union, as some observers fear.

The obvious parallel, which must have struck everyone, is the similarity of these events to the revolutions of 1848-49, when a great upsurge of liberal and democratic feeling toppled governments in Paris, Rome, Venice, Berlin, Dresden, Vienna, Budapest. The late Sir Lewis Namier attributed the failure of these revolutions – for by 1850 they were all dead – to their having been, in his words, ‘a Revolution of Intellectuals’. However this may be, we also know that it was the forces unleashed against these revolutions – the armies of Prussia and Austria-Hungary, the southern Slav battalions, the agents of Napoleon III in France and Italy, and, above all, the Czar’s troops in Budapest – that crushed this movement and restored something like the status quo. Fortunately, the situation today does not look similar. The current movements have developed into genuine, spontaneous popular risings, which plainly embrace all classes. We can remain optimistic.

Apart from these general reflections, there is a particular thing which has struck me forcibly – the survival, against all odds, of the Russian intelligentsia. An intelligentsia is not identical with intellectuals. Intellectuals are persons who, as someone said, simply want ideas to be as interesting as possible. Intelligentsia, however, is a Russian word and a Russian phenomenon. Born in the second quarter of the nineteenth century, it was a movement of the educated, morally sensitive Russians stirred to indignation by an obscurantist Church; by a brutally oppressive state indifferent to the squalor, poverty and illiteracy in which the great majority of the population lived; by a governing class which they saw as trampling on human rights and impeding moral and intellectual progress. They believed in personal and political liberty, in the removal of irrational social inequalities and in truth, which they identified to some degree with scientific progress. They held a view of enlightenment that they associated with Western liberalism and democracy.

The intelligentsia, for the most part, consisted of members of the professions. The best known were the writers – all the great names (even Dostoyevsky in his younger days) were in various degrees and fashions engaged in the fight for freedom. It was the descendants of these people who were largely responsible for making the February Revolution of 1917. Some of its members who believed in extreme measures took part in the suppression of this revolution and the establishment of Soviet Communism in Russia, and later elsewhere. In due course the intelligentsia was by degrees systematically destroyed, but it did not wholly perish.

When I was in the Soviet Union in 1945, I met not only two great poets and their friends and allies who had grown to maturity before the Revolution, but also younger people, mostly children or grandchildren of academics, librarians, museum-keepers, translators and other members of the old intelligentsia, who had managed to survive in obscure corners of Soviet society. But there seemed to be not many of them left. There was, of course, a term ‘Soviet intelligentsia’, often used in state publications, and meaning members of professions. But there was little evidence that this term was much more than a homonym, that they were in fact heirs of the intelligentsia in the older sense, men and women who pursued the ideals which I have mentioned. My impression was that what remained of the true intelligentsia was dying.

In the course of the last two years, I have discovered, to my great surprise and delight, that I was mistaken. I have met Soviet citizens, comparatively young, and clearly representative of a large number of similar people, who seemed to have retained the moral character, the intellectual integrity, the sensitive imagination and immense human attractiveness of the old intelligentsia. They are to be found mainly among writers, musicians, painters, artists in many spheres – the theatre and cinema – and, of course, among academics. The most famous among them, Andrey Dimitrievich Skaharov, would have been perfectly at home in the world of Turgenev, Herzen, Belinsky, Saltykov, Annenkov and their friends in the 1840s and 50s. Sakharov, whose untimely end I mourn as deeply as anyone, seems to me to belong heart and soul to this noble tradition. His scientific outlook, unbelievable courage, physical and moral, above all his unswerving dedication to truth, makes it impossible not to see him as the ideal representative, in our time, of all that was pure-hearted and humane in the members of the intelligentsia, old and new. Moreover, like them, and I speak from personal acquaintance, he was civilized to his fingertips and possessed what I can only call great moral charm. His vigorous intellect and lively interest in books, ideas, people, political issues seemed to me, tired as he was, to have survived his terrible maltreatment. Nor was he alone. The survival of the entire culture to which he belonged underneath the ashes and rubble of dreadful historical experience appears to me a miraculous fact. Surely this gives grounds for optimism. What is true of Russia may be even more true of the other peoples who are throwing off their shackles – where the oppressors have been in power for a shorter period and where civilized values and memories of past freedom are a living force in the still unexhausted survivors of an earlier time.

The study of the ideas and activities of the nineteenth-century Russian intelligentsia has occupied me for some years, and to find that, so far from being buried in the past, this movement – as it is still right to call it – has survived and is regaining its health and freedom, is a revelation and a source of great delight to me. The Russians are a great people, their creative powers are immense, and, once set free, there is no telling what they may give to the world. A new barbarism is always possible, but I see little prospect of it at present. That evils can, after all, be conquered, that the end of enslavement is in progress, are things of which men can be reasonably proud.

Andrei Sinyavsky

Translated from the Russian by Michael Glenny

Many of our friends from the Soviet Union come to visit us in Paris – Soviet writers, artists and journalists – and I ask all of them: ‘Who is running the country? And what’s going to happen tomorrow?’ For a long time now I have been getting the same answer: ‘We don’t know!’

Just think: this was my country, where for decades nothing happened, where one day was exactly like another, and you could predict the future years and kilometres ahead (turn to the right, and you join the Communist Party, eventually becoming one of the bosses; turn to the left, and they call you a dissident and put you in prison). Suddenly the country doesn’t know what will happen next week. Nobody in the world knows.

We, the Russians, are once more in the vanguard, once more the most interesting phenomenon on earth – I would even say as an artistic phenomenon: like a novel whose ending none of us knows.

Little was needed to make this happen. First the people were granted a relative freedom of speech. Second the idea of global Communism, for the sake of which so many pointless sacrifices had been made, was abolished (or at least forgotten for a while). And the very soil, as a result, proved to be immediately fruitful.

But it is here, too, that we find new dangers growing within the empire at its moment of transformation: the dangers of xenophobia and ethnic conflict. In particular, to judge from the press, I see a new form of Russian Nazism gathering strength. I see the seeds of it, for instance, in a work recently published in Moscow by Igor Shafarevich entitled Russophobia, in which, developing one of Solzhenitsyn’s ideas, the author builds up the myth of the Jews as the original and principal enemy of the Russian people. Igor Shafarevich is a world-class mathematician, a member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences, an honorary member or professor of several European academies and universities. Yet the argument of his book coincides with the theoreticians of German Nazism, from Hitler to Rosenberg (perhaps the coincidence is unconscious, but there are passages which seem like verbatim allusions). The thesis is couched in measured, reflective, academic terms. It can be summarized thus: a small people, that is the Jews, (the Russophobes of the titles), is waging a centuries-old battle to the death against a large nation (in this case Russia): ‘Russophobe literature is strongly influenced by Jewish nationalist sentiments,’ he writes. Among the Russophobes he numbers Galich and Vysotsky, Korzhavin and Amalrik, Grossman and Tarkovsky, Ilf and Petrov, Byalik and Babel. In the past, ‘the typical representative of this tendency [in this particular instance an anti-German one] was Heine.’ Similar efforts at domination by representatives of this small nation are found, he explains, in ‘the influence of Freud as a thinker, the fame of the composer Schönberg, the artist Picasso, the writer Kafka or the poet Brodsky.’ The aim of this small nation, writes Shafarevich in conclusion, is the ultimate destruction of the religious and national foundations of our life, and at the same time, given the first opportunity, the ruthlessly purposive subversion of our national destiny, resulting in a new and terminal catastrophe, after which probably nothing will be left of our [ie the Russian] people.’

I am by no means against the publication of Shafarevich’s

Russophobia, especially in Russia, after so many years of being deprived of the freedom of expression. But I am worried by the silence surrounding the appearance of this book, the absence of any serious discussion of it. The danger of the game Shafarevich is playing lies not so much in his ideas, which are trivial enough, as in the soil on which they are falling.

Anti-Semitic ideas have been taken up in the Soviet Union by both the mob and intellectuals. Two events took place recently in Moscow: an anti-Semitic demonstration by the society known as Pamyat (‘Memory’), which was held in Red Square (and therefore had official permission from the authorities), and an anti-Semitic plenary session of the Union of Writers of the Russian Federation. The demonstration of the mob ended with it singing a song whose opening lines are:

Arise, thou mighty nation,

Arise, take up the sword!

Against the Yids’ foul domination,

Against that cursed horde

The speakers at the plenary meeting of Russian intellectuals included the distinguished novelists Valentin Rasputin and Vassily Bielov. Rasputin accompanied Gorbachev on his visit to China; Bielov went with him to Finland. The meeting ended with the editor of the literary journal Octoberbeing dismissed for publishing works described as ‘anti-patriotic and Russophobe’.

Nationalism in itself is not a serious threat – it can, on occasion, actually be of value to a nation – until it starts to produce, without any substantive grounds, that venomous by-product: ‘the enemy’. In the past, the Soviet Union had the ‘class enemy’. The struggle against the class enemy grew more and more intense just as all classes were being liquidated until indeed there were no more classes left. And now the Russian nationalists, who call themselves ‘patriots’, have summoned up ‘Russophobia’, a modification of the Leninist-Stalinist idea of ‘bourgeois encirclement’ and ‘bourgeois penetration’. The ‘Russophobe’ is a variant of those terrible Stalinist inventions ‘enemy of the people’ and ‘ideological saboteur’.

All of them are, of course, myths.

But the definition of ‘Russophobia’ has expanded to threatening dimensions. It incorporates the ‘soul-less’ West, poisoned through and through by pornography and drug addiction and longing only to destroy the Russian people, who are the incarnation of mankind’s conscience. Then there are the enemies within – the liberals and democrats, the intellectuals, the black-market operators, the dissidents and the Jews. Both the old-style myth of the bourgeois threat and the new version – Russophobia – I find equally repellent, not only for their vulgarity but for the very dangerous undertone of hatred which they contain. After all, if Russia’s ills and misfortunes derive from its Western Russophobe enemies and its internal Russophobe enemies, and these enemies want to destroy the soul, the body and the memory of the nation, of Russian culture and of the entire Russian people, why not put an end to all these ‘parasites’, ‘cosmopolitans’ and ‘pluralists’ at a stroke?

When a multinational empire disintegrates, or finds itself on the verge of falling apart, the peoples who constitute it develop various forms of nationalism. This has marked the break-up of many great empires. A powerful, militant Russian nationalism is arising to shore up and protect the Soviet empire. As I see it from here, the Soviet Union at the moment is like a garage full of cans of petrol which are giving off so much vapour that the place is ready to explode. In that volatile atmosphere, the Russian nationalists are playing with matches, and one of the most inflammatory matches is called ‘Russophobia’.

Why do they play with these matches? To bring about a national religious revival? God preserve us from any such thing! And may Christ forgive us for once again linking His name with the urge to launch massacres and pogroms.

Abraham Brumberg

My grandfather, a prosperous merchant equally at home among cosmopolitan financiers and in the insular world of his native Lithuanian shtetl, lived and died in History. In 1918, he was stood up against a wall and shot, together with two of his sons, by Red Army conscripts. It was merely a chance historical moment that made my grandfather and his sons victims of the Bolshevik Revolution rather than of its enemies – or of local anti-Semitic cut-throats. But it cast a long shadow.

My father, a free-thinking socialist, was forced to flee the country in 1925. He had been involved in one of those student strikes which the Polish police, not keen on ideological distinctions, regarded as yet another ‘Judeo-Communist’ plot. Nine years later, back in Poland as director of a children’s sanatorium maintained by the Jewish socialist ‘Bund’, he used his revolver (the first and only time in his life) to fight off a group of Communists bent on destroying this bastion of ‘social fascism’. Another chance historical moment?

When the war broke out, my parents and I set off on a trek that eventually took us from Warsaw to Soviet-occupied Vilna. Since the NKVD was combing the town for socialists, liberals, ‘nationalists’ and other enemies of the people, my father went into hiding, leaving my mother and me with local relatives. He surfaced several weeks later, when Vilna (now Vilnius) was turned over to Lithuania, only to disappear again when Soviet troops reoccupied Lithuania and the other two Baltic states.

For obvious reasons I, at the age of twelve, turned out to be the sole hold-out in my class against the allurements of revolutionary rhetoric. All the others had joined the Red Pioneers. One day, we were reading aloud a hymn to Stalin written by Itzik Feffer, a Soviet Yiddish poet later executed as a spy. Each student was told to read one stanza. When it was my turn, I declaimed, though apparently without enough ardour:

He is deeper than the oceans,

He is higher than the peaks,

There is no one on this globe

Quite remotely like him.

Apparently, for my schoolmates, on the lookout for evidence of ideological turpitude, loudly demanded that the teacher force me to ‘read the stanza again – with more feeling.’ The teacher, not a Communist, looked sad – and complied. So did I, but the lesson sank in: terror needs no jails or bayonets to be effective.

My family managed to reach the United States in 1941. Wracked by questions, I began reading voraciously, seeking answers in works by eyewitnesses to history, erstwhile believers, anathematized enemies (for instance Leon Trotsky) and sympathetic but critical scholars such as Sidney Hook and William H. Chamberlin. I memorized entire chunks of the report by the Commission of Inquiry on the first two Moscow Trials (John Dewey, Not Guilty) and hurled them at my gauchist fellow students in New York’s City College. We argued about the Communist coups in Eastern Europe, whether Tito was a fascist beast, and whether Stalin was the ‘gravedigger of the Revolution’ or – in the words of Isaac Deutscher – the ‘man who dragged Russia, screaming and kicking, into the twentieth century.’

And now, suddenly, there is change. In Czechoslovakia, the change was the death knell of the Communist Party, and it sounded when the workers laid down their tools on 27 November. But in East Germany, the change came the moment that popular discontent turned to fury at the disclosures of massive corruption within the red bourgeoisie. The Germans, apparently, actually believed that Honecker et al lived as ascetically as Vladimir Ilyich Lenin. Now they know otherwise. Will they still ask themselves how dedicated Communists who had spent years in Hitler’s jails and camps had turned into sanctimonious revellers? Or will they conclude that Communists had always been, au fond, a pack of gangsters? In Poland, that seems to be the conclusion. ‘Nothing but a pack of gangsters’ is now the preferred sobriquet for all Communists, used indiscriminately even by Solidarity leaders whose past ties to the party were based on rather more than lust for power and privileges.

Questions: they generate more questions. Stalin was a monster, Lenin hardly a saint and Marx a prophet manqué; but have their mistakes, misdeeds and villainies sullied the goal of a just society? Did the path chosen by Lenin and the other founders of the Soviet state lead inevitably to Stalinism? Can we assume that all those questions that I and so many others agonized over have now, in these last months, been fully answered and disposed of?

Not likely.

In some countries, we now watch the discredited order and equally discredited myths giving way to virulent nationalism, ethnic hatreds and enthusiasm for unrestrained laissez-faire. I fear that the demise of Communism is to be accompanied not by the dispelling of the long shadow of history; it is to be accompanied by the erosion of tolerance and of historical memory.

I know that the current historical moment is as splendid as it is unique. But I am also aware of past moments. They include the death of Stalin, Khruschev’s speech in 1956, the Hungarian insurrection, the outbreaks of unrest in East Germany and Poland, the Prague Spring, the birth of Solidarity in Poland, the rise of Gorbachev. Each of them was distinct, and each hastened the advent of the present Moment. And I am aware, too, of the deceits bred by faulty memory. Perhaps I owe this awareness to my father, whose bitter brushes with History taught him to suspect facile simplicities, to respect distinctions, and to ponder over unanswered questions. Like his own father, he lived his life in History. So have I. We all do, whether we know it or not.

Noel Annan

In the last few weeks Berlin has haunted my mind. It is the only place where I have taken an active part in an election. That was in the early months of 1946 when elections were to be held in the city and in the Soviet Zone. The Soviet authorities realized that the Communist Party had no hope of winning. So they declared that, to avoid the working classes being split as they had been in 1933, the Social Democrat Party should amalgamate with the Communist Party to form the Socialist Unity Party (SED). In the Soviet Zone the Social Democrats were forced to submit. Anyone who resisted found himself in jail.

But in Berlin things were different. The rank and file of the Social Democrats were against amalgamation, but their leader Otto Grotewohl was a weak, vain man and under pressure from the Russians he announced that his party in Berlin intended to merge with the Communists. He misjudged the temper of the Berlin people. He also misjudged the temper of the Western Allies. My chief, Kit Steel, who later became the British Ambassador to the Federal Republic, asked me to help the Social Democrats, since I was responsible for the development of German political parties. And, with further assistance from my American colleagues, we organized the campaign against amalgamation. In those days no German was allowed to write or say anything that could be construed as criticism of the occupying powers. It therefore was left to me to write articles reminding Berliners of the political record of Ulbricht, the Communist Party leader. Ulbricht in exile had defended the Nazi-Soviet pact, had attacked those who resisted Hitler and had referred to the Social Democrats in approved Party style as social fascists. The delegates of the Social Democrat Party had to meet in the Soviet sector of Berlin to vote. With considerable courage they voted overwhelmingly against the merger.

Thereafter the Communists improved their technique of taking over democracies. Czechoslovakia fell, and in 1948 Stalin decided to eliminate Berlin. Following the Soviet blockade of the city, I returned to Berlin to circumstances which were both dramatic and farcical. Each of the four powers was busy producing cultural manifestations to impress the Berliners. The Russians sent a 400-strong Cossack choir to sing in the Alexanderplatz. The British sent madrigal singers from Cambridge and a university drama society to play Measure for Measure and The White Devil in which I was cast as Cardinal Montecelso. What effect this had on the Berliners I cannot imagine, but despite our acting, their morale rose steadily as the roar of aircraft landing at Tempelhof day and night continued.

The years passed. The Wall was built. When it was breached and the Social Democrats in East Germany finally announced their intention to break away from the Communist Party, the chapter that began for me in the winter of 1945–1946 closed.

My generation grew up in the thirties. We lived under the shadow of a great apocalyptic political movement that divided the culture of Europe as profoundly as the division between Catholics and Protestants in the late sixteenth and seventeenth century. The debates about dialectical materialism and demand theory were as bitter as those about the Real Presence and Justification by Faith. It is quite untrue that the most intelligent undergraduates in the thirties were Communists or Marxists, but it is an equal error not to recognize how the Depression, unemployment and the rise of Hitler convinced some of them that the Marxist explanation of these events was right. When Arthur Koestler first read Marx he said the new light seemed ‘to pour from all directions across the skull . . . There was now an answer to every question, doubts and conflicts were a matter of the tortured past.’

No one can have a glimmering of the feelings of the left before the war who does not understand its obsession with the Spanish Civil War: it was the only authentic war in which the forces for good were ranged against the forces for evil. The war of 1939 was not authentic: Britain was being led by men who had failed to stand up to Fascism. For the left the war became authentic only in 1941. The left rejoiced as the Red Army eliminated the regimes of the kings and regents of Eastern European countries, and spoke with scorn about the Polish officers in London. These intellectuals believed Europe to be on the verge of a people’s revolution. Meeting Kingsley Martin when I returned from Berlin at the end of 1946, I found he believed that, but for the Anglo-American armies, Europe would have been governed by socialist regimes installed by popular acclamation.

In fact this vision of the left bore no relation to the simple desires of human beings in Europe. All they wanted was food and shelter and freedom from the authorities. It is the same today. The people in Eastern Europe have not rebelled in the name of a great cause. They rebelled against the regimentation and dreariness of life. They want the consumer goods of the West and freedom from arbitrary authorities.

There is elation at seeing political prisoners released, secret police headquarters ransacked and, perhaps, Gulags emptied. Communism has lost whatever moral force it had – even the Euro-Communism that existed in Italy and in France, in Sartre’s day, with its dazzling and bogus pretensions. It has not lost its appeal in the Third World. There will continue to be countries where, exasperated by corrupt dictators and grasping landlords, the peasants and intellectuals become inspired by that bitter hatred of oppression and injustice that moved Marx.

But in Europe everyone seems convinced that the dark ages can never return. I am by nature more sceptical and cynical. The history of reforming tsars and progressive ministers in Russia is not encouraging. People still have too great faith in the ability of government to defeat the changes brought about by fortune, and they become disillusioned with its failure to protect them from the chances of fate. Still, this Christmas it is better to hope than to fear.

Günter Kunert

Translated from the German by Harriet Goodman

At times of crisis in Germany there is talk of dreams, more so probably than in any other country in the world. Romanticism is a quintessentially German product, a museum piece that has taken on a new relevance with the Wall in Berlin fallen; writers from the East and West, falling suddenly into each other’s arms appear to be as Romantic as their eighteenth- and nineteenth-century counterparts. At no time was this more apparent than on 29 November 1989 when a number of authors and intellectuals in East Berlin – among them, Stefan Heym, Volker Braun, Ghrista Wolf – published an appeal urging people to uphold the ‘moral values’ of the socialism of the German Democratic Republic and to bring into being a ‘new’, a ‘true’, a ‘genuine’ socialism.

We see today the crowds in Leipzig and East Berlin. They are raging at a system that has cheated them all their lives with its feudal structure of hierarchies. We see people whose most heartfelt desire is for an existence without fear or deprivation – a normal existence. And they are answered by writers and intellectuals who, having never known such deprivation, call for a purified, revitalized socialism.

What is going on in the heads of the authors of this declaration? Who are they? They seem to have set themselves up as the Praeceptor Germaniae, the old German head teacher, lecturing the children as to what they should and should not do, and the role of lecturer, ‘teacher’, ‘people’s educator’, is, of course, the favourite pose of the German poet and writer. What is this ‘democratic socialism’ and how is it supposed to inspire people who have been led around by the nose for forty years? It has little to do with them. Is it nothing more than the untested brainchild of an educated and domineering mentality? The authors of the declaration of 29 November 1989 set themselves up, once again, to dictate how life should be and how we should behave within their hypothetical construct, revealing, thus, their contempt for ordinary people. The ordinary people on the streets of East Germany have not the slightest interest in revitalizing socialism of any sort. They are not asking for a new system; they are asking, understandably, for a better life. And since no one has yet given them a concrete answer, they are now demanding the reunification of Germany as their last hope of rising out of the chaos of a state that has done nothing but exploit them. The intellectuals of course protest that reunification would mean ‘selling out’ East Germany, reducing it to a colony of the Federal Republic, but their protest hardly matters to the people on the streets. A better life is what matters to them, whatever the flag and whatever the government; no one wants to wait any longer. For forty years they have been fed on empty promises: why should a promise of ‘democratic socialism’ suddenly satisfy them?

Socialism is finished as an alternative to other systems of society, and it is disappearing from history. It is not yet clear what will take its place. This uncertainty is profoundly disturbing to East German intellectuals, who have always sought to shore themselves up with certainties and absolutes, however fictitious. The German intellectual, one could say in a variation on one of Brecht’s Keuner stories, needs a God. He cannot exist without ‘isms’. So he shuts his eyes to the facts and clings to a Fata Morgana made of paper untainted by the filth and blood of reality.

Tony Benn

Perestroika and glasnost have far-reaching consequences for the thinking of socialists all over the world. What is needed is the emergence of more democratic control, at every level of Soviet society – political and economic, regional and national – if socialism is to remain rooted in the experience of those it is intended to serve. I suspect that some of the most influential pressures for change are coming from the intelligentsia, who were prevented from publishing what they wished; from the media, who suffered under the same restraints; and from the managers, who wished to have greater power. If those are the major forced now at work in the USSR, then working people, as a whole, will have to assert their own determination not to fall under the control of a new group of governors, in the name of reform.

Having said that, it is also important to recognize the immense achievements of the Soviet government since 1917. It was the first workers’ state in the world. It pioneered huge advances in education and health, in housing and social welfare. The Soviet Union assisted liberation movements in every continent, and immense sacrifices made by its own people during the Second Would War made possible the defeat of Fascism.

In recent years the Gorbachev initiatives in the field of disarmament have put the NATO strategists on the defensive, and given the peace movement in the West the opening it has needed to press for more positive responses and a reduction of the arms burden. People have always tended to be sceptical about disarmament plans, suspecting that they were merely propaganda moves to embarrass another country. But when Gorbachev made it clear that he wanted disarmament to ease the burden of his arms budget and to improve the living standards of the Soviet people, the reaction in Britain was ‘We want to do the same.’ In Britain today Gorbachev is far more popular than Reagan or Bush.

I can visualize the development of a form of democracy, inside the USSR, which permits a popular choice of leaders, each of whom is committed to upholding socialism, in much the same way as in the West the political parties vying for power are, in effect, competing for the privilege of running capitalism.

Czesław Miłosz

What will happen next? Does the victory of the multi-party system in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe mean the end of their estrangement from the West? Will they, by introducing the classical division of powers – a legislature, executive and judiciary – recognize the supremacy of all Western values? Will the years of suffering under totalitarian rule be obliterated, erased and the people start from scratch? Should the thinkers, poets and artists join their Western colleagues in the somewhat marginal role assigned to them in societies busy with selling and buying?

These questions are important, for they have to do with the deeper meaning of the twentieth century. For many decades the two blocs followed different cultural paths: the Western open, the Eastern clandestine. Fulfilling Friedrich Nietzsche’s prophecy about ‘European nihilism’ Western thought and art did not offer us, in the East, much nourishment. Most Western writers seemed frivolous and irresponsible; measured by artistic exigencies, they appeared as indifferent to a hierarchy of quality and of taste. Most Western film- and television makers shocked us by their hare-brainedness and lack of concern for the needs of human imagination, which gets dulled by being constantly exposed to scenes of violence and perversion. We did not respect the leading English, French and American intellectuals who praised the ugly totalitarian reality from a distance. We shrugged when their names, be it Bernard Shaw or Jean-Paul Sartre, were mentioned. We in the East knew the words Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, but the West did not learn Kolyma, Vorkuta, Katyn.

The failure of Marx’s vision has created the need for another vision, not for a rejection of all visions. I do not speak of ‘socialism with a human face’, for that belongs to the past. I speak instead about a concern with society, civilization and humanity in a period when the nineteenth-century idea of progress has died out and a related idea, Communist revolution, has disintegrated. What remains today is the idea of responsibility, which works against the loneliness and indifference of an individual living in the belly of a whale. Together with historical memory, the belief in personal responsibility has contributed to the Solidarity movement in Poland, the national fronts in the Baltic States, the Civic Forum in Czechoslovakia. I hope that the turmoil in these countries has not been a temporary phase, a passage to an ordinary society of earners and consumers, but rather the birth of a new form of human interaction, of a non-utopian style and vision.

Ivan Klíma

Translated from the Czech by Daphne Dorrell

The first pictures of the Prague demonstration of 17 November were of young girls placing flowers on shields held by riot police. Late the police got rough, but their furious brutality failed to provoke a single violent response. Not one car was damaged, not one window smashed during daily demonstrations by hundreds of thousands of people. Posters stuck up on the walls of houses, in metro stations, on shop windows and in trams by the striking students called for peaceful protest. Flowers became the symbol of Civic Forum.

It is only recently that we have seen the fragility of totalitarian power. Is it really possible that a few days of protest – unique in the history of revolutions for their peacefulness – could topple a regime which had harassed our citizens for four decades?

The rest of the world had all but forgotten the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by the armies of five countries. Even now, our nation has barely recovered from that invasion; what did not recover was the leading force in the country, the Communist Party. By subsequently making approval of the invasion and the occupation a condition of membership, the Party deprived itself of almost all patriotic and worthy members, becoming for the rest of the nation a symbol of moral decay and betrayal. The government, then stripped of its authority and its intelligence, went on to devastate the country culturally, morally and materially. An economically mature country fell back among the developing countries, while achieving a notable success in atmospheric pollution, incidence of malignant tumours and short life expectancy.

Unrestrained power breeds arrogance. And arrogance threatens not only the subject but also the ruler. In Czechoslovakia the ruling party, deprived of an elite and of any outstanding personalities, combined arrogance with provocative stupidity. It persisted obstinately in defending the occupation of Czechoslovakia, indeed as an act of deliverance at a time when even the invaders themselves were re-examining their past. The government actually went so far as to suggest that the apologies offered by the Polish and Hungarian governments for their role in the invasion constituted interference in the internal affairs of the country. How could the nation consider such a government as its own?

The months leading up to the events of November, however static they may have seemed compared with the agitation in the neighbouring countries, were in fact a period of waiting for circumstances for change. The regime, unable to discern its utter isolation, in relation to both its own nation and the community of nations, reacted in its usual manner to a peaceful demonstration to commemorate the death of a student murdered by the Nazis fifty years ago. It could not have picked a worse moment – the patience of the silent nation had snapped; the circumstances had finally changed.

We, who had consistently tried to show the bankruptcy of the regime, were surprised at how quickly it collapsed under the blows of that one weapon, truth, voiced by demonstrators – students and actors who immediately went to the country to win over people – and then spread by a media no longer willing to serve a mendacious and brutal regime. As such non-violence was the only weapon we needed to use against violent power. Will those who were robbed, harassed and humiliated continue to be so magnanimous? As long as they can be they have in their power to realize the idea of a democratic Europe, a Europe for the next millennium, a Europe of nations living in mutual domestic peace.

Stephen Spender

Perhaps because I am eighty what is happening today in the Soviet Union, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria has the effect of making me feel that I am witnessing apocalyptic events out of the Book of Revelations. I do not apologize for beginning on this personal note. For the collapse of the totalitarian regimes in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe is something that I had given up hope of witnessing in my lifetime. I was sure that it would happen eventually but that it would be perpetually postponed to the next century, after the millennium. I now have the almost biblical sense of being privileged to watch a miracle.

Perhaps some young people have the same kind of feeling. A historic event may seem to contemporaries part of a larger impersonal history being unfolded before their eyes, and yet at the same time they strike each separately as being his or her intensely felt personal experience. The assassination of President Kennedy had this effect on thousands of people who, notoriously almost, remember what they were doing at the moment when they heard the news of Kennedy’s death.

Judging from the newspapers, many people in the West – especially conservative politicians – take what they call ‘the end of Communism’ to signify the defeat of the evil Communist Satan and the triumph of the Capitalist God in a Manichean struggle between the forces of Good (Capitalism) and Evil (Communism). This seems to me a dangerously false reading of recent events. What has triumphed in Democracy, the will of the people, and in a very unideological, politically scarcely realized, form. And this is not because socialism (‘socialism with a human face’) has failed but because Marxist ideology, tied to the concept of ‘the dictatorship of the proletariat’, has broken down.

The evil of Communism is that Marxist leaders, beginning with Lenin, believed that any means justified the overcoming of capitalism. Communist leaders everywhere became corrupt as a consequence of their having absolute power. But today, when the corruption of the older generation of Communist leaders in East Germany is exposed, it is perhaps salutary to remember that in their youth many of these leaders were heroic idealists (though preaching ‘historical materialism’). They were opponents of Hitler, and several were killed or imprisoned, ending their lives in concentration camps. Ernst Thaelmann, the German Communist leader, murdered by the Nazis in Buchenwald concentration camp in August 1944, would almost certainly be in the same position as his follower Erich Honecker, if he were alive today.

Perhaps it is too simple to read these events in terms of the political divisions which have dominated nations in the twentieth century. Of course resurgent nationalism and shortage of consumer goods help produce a revolutionary situation, but there is a historically unprecedented negative factor which seems to me tremendously important, especially among students and intellectuals. This might be called ‘the boredom factor’. Life under a dictatorship of old-style ideologists, whether in Russia, Eastern Europe or China, is extremely boring. Moreover, owing to modern systems of communication people living under dictatorships are made aware of the boredom of the system: the flow of information from the outside is unstoppable. The Berlin Wall may have prevented East Berliners reaching the West, but it was leaped over and penetrated at a million points by TV and radio bringing East Berliners news and images of the lifestyle, vitality and competitiveness of the West.

Commentators have had difficulty defining, in political terms of left or right, the changes taking place in the Communist world today. Apart from nationalism and very pressing economic problems the movement is perhaps more a cultural than a clearly definable political revolution. It is led by intellectuals and students who know what they want – freedom of self-expression and removal of the dead weight of censorship and Party dogma – better than they know the politics which they wish to see replace Communism.

The crowds of rejoicing young people who have got rid of their Communist Party leaders have streamed across the TV screens of Western Europe. Mass demonstrations proved their point when they were seen by a world in moving photographs. Violence had become superfluous and unnecessary. No one needed to be killed, and no Bastilles stormed. This theatre is the living truth of the liberation movements. It is significant that Vaclav Havel is a playwright. His Civic Forum has the look of characters in search of a party and a policy. What we see may show that we have moved beyond the nineteenth- and twentieth-century cycle of revolutions – murder followed by counter-revolutions, also murderous – to a period when great political-cultural changes are acts of recognition of changed states of consciousness among people, made apparent by faits accomplis by the mass media.

But that is to look beyond the present, into the twenty-first century. Many things may go wrong. Gorbachev may fail and be succeeded by the military. Problems caused by mass starvation may supersede all others and may produce widespread death and violence. Nevertheless the recent events have shown that dictatorial regimes are incapable of replacing an old leadership with youthful leaders without the regimes and their ideology crumbling. There were signs of this in 1968 when the movement forward in Communist societies was reversed in Czechoslovakia by Soviet troops. It is difficult to believe that a reversal, if it happens, will be as effective – not even in China. If the present revolution is stopped in any one place, to be superseded by dictatorship, the media will assure that the consciousness of a democratic world, flooding in, will sooner or later break down the prison walls of the dictatorship.

Mercea Dinescu

Translated from the Romanian by Fiona Tupper-Carey

Not long ago, in the icy Siberian plains, a few hard-frozen mammoths were discovered. The discoverers were astonished to find chamomile flowers inside their bellies. I recalled the incident when I came upon an article in the Western press entitled ‘Last Stalinist mammoth left in Romania’. I greatly fear that, when the social climate in Romania does change, we will not find any chamomile flowers inside the belly of our Stalinist beast, but several dead bodies. People from the Jiu valley, from Barsov, Timişoara, Cluj, Iaşi, Tirgu Mures, and Bucharest have been and are still being swallowed alive. They are people about whom little, or even nothing at all, is known, who were courageous enough to vent their exasperation, even if only within their communities.