I

Ko au te whenua, te whenua ko au.

Mauri

Mana

Never thought of my body as separate from the mauri of every living thing or every thing and body that ever existed. Non-human matter and beings encounter one another constantly. For Maaori our bodies are shaped by an awareness of non-human and human dynamics, as we are physically embedded into the whenua (land, placenta) and our bodies stretch up and down like endless poi between Ranginui and Papatuuaanuku.1

Jane Bennett refers to this matter or what we would call mauri or mana as being the ‘material’ or the ‘thingness’: ‘a cultivated, patient, sensory attentiveness to non-human forces.’ I worry for all of humanity that our relationship with the so-called ‘non-human’ is so detached from our day-to-day lives and written about in such an austere way. I felt frustrated in class recently discussing Bennett’s ‘plant-thinking’ as a kind of adaptation of Deleuzian ‘rhizomes.’

Someone please explain Deleuze to me or I will fucking kill you.

The everyday entanglement of nature and culture.

I imagine all bodies and all entities like jellyfish or pomegranate seeds or the yellow goop inside a kina or the salty water sack covering an oyster. My brain is a physical entity and gunk and ‘it contains cells, tissue, fluid, neurons . . . blood vessels, matter white and black and grey.’2 Shooting electrons swimming under the water in giant, cold, metal pipes. Wet. Moist. Slimy. Dripping. Silicon. Multiple realities are thrown into being. They overlap, map, and diverge across time and space. Time collapses and reveals itself as both porous and arbitrary.

Aura?

Plant-thinking?

When I think of the conception of the ‘soul’, I cannot help but return to the banality of continental philosophy by mentioning Socrates’ view of the soul as trapped inside the tomb of the body, only released upon death. I wonder if a soul is like a wairua, but that seems too limited. I imagine a wairua with the power of a thousand hearts beating together simultaneously in the air, the soil, and in the living and non-living matter that encompasses everything. I think of cicadas rippling through the night, of worms soaking deep into tree roots and of weeds boundlessly taking over the cathedral in Ootautahi.

Plants are not a singular organism, but a living totality, reaching up through the plastic and concrete cracks on ancient cobblestones. The ability of plants to grow via roots that sprawl together and react in a kind of utopia reminds me of the ways that hemp plants were used in Chernobyl to clean up nuclear waste. Or how older gorse plants are used for native plant regeneration in the Banks Peninsula. I think too of the watercress that grows at the front of my parents’ house. It is plentiful, but you cannot eat it. Green algae floats around the edges of the swampland as rhododendrons bloom above.

Grain hybrids

Irrigation systems

Fertilisers

Pesticides.

Global food production

‘Green Revolution’

100% pure

‘In decolonization, there is therefore the need of a complete calling in question of the colonial situation.’3

I dedicated much of my life to self-‘improvement’: To be the best of both worlds, which is impossible, because to accept whiteness is to neglect te ao Maaori. When I think of this ideology of improvement – of being the best, of being the winner, of being the most productive – I can’t help but think of how it is rooted in the abstraction of land; using English common law colonists measured land in relation to the labour of cultivation, dividing Papatuuaanuku into usages and rendering her value in the form of commodity production.4

Ko au te whenua, te whenua ko au.

Papatuuaanuku’s soil has been ravaged by irresponsible agricultural practices to produce equal amounts of waste as food. This process of extraction is marred by colonialism, not merely because this is stolen land but because it abstracts our bodies from the whenua in order to justify the settler’s presence as part of an endless plunder. This logic of abstraction – title by registration, part of the British colonial project designed to sever Indigenous people from their lands – is rooted in the transformation of ‘the idea of property (in land) as a socially embedded set of relations premised on use, political hierarchies, and exchange, to a commodity vision of land that rendered it fungible in the same way as any other commodity.’

As part of the British colonial project land was confiscated based on whether it was deemed agriculturally viable – if certain Indigenous people had or had not enacted an agricultural plan based around an idealised European model for production and extraction (commercial trade and marketised exchange). Marx wrote on this disruption of this free-flowing relation between nature and man: ‘Nature does not produce on the one hand owners of money or commodities, and on the other hand men possessing nothing but their own labour-power. This relation has no basis in natural history, nor does it have a social basis common to all periods of human history. It is clearly the result of a past historical development, the product of many economic revolutions, of the extinction of a whole series of older formations of social production.’

The current state of the world, the seemingly irreparable damage done to our waterways, soil and vegetal life is the result of colonialism – of an insidious process of acquisition, extraction, and violence. To take and divide land based on ‘productivity’ debased the ecological protocols Indigenous people had had in place to manage resources for millennia.

In Aotearoa before colonisation we had a booming trade system across the Pacific, but we managed our resources, only taking what was needed to survive. This was based around tikanga specific to different peoples, but incurred invocations or karakia to welcome and thank our ancestors (Ranginui, Tangaroa, et cetera) for these gifts, such as fish from the sea or potatoes from the soil.

II

Hiding in kumara pits on the side of volcanoes, I was born with an egg inside me ready to be baked. I dream my skin is made of harakeke. Two estranged friends slowly soften my coarse flesh with oyster shells. I am in pain but they ignore my karanga and I hear their thunderous laughter rolling up towards Ranginui’s echoing sky. Sometimes their laughter is intercut with the Seinfeld theme song. They were trying to make me softer, but I refused.

My whenua is buried at our house on Smith Street in Matamata. My mother told me when my brother was born the nurses had already thrown his whenua away.

My atua waahine streams down my thigh, as I wake dripping in steaming wai. Hine-te-iwaiwa my cycle can’t keep up with your shifting of the moon.

A friend tells me it’s just as well I didn’t have a baby, because of the impending ends of the world. I never thought it was possible to become pregnant because of the amount of irresponsible sex I’ve had that never resulted in a child. So when a ‘thing’ unsuspectedly grew inside me and took over my body I was stunned. In a way that’s still difficult to make sense of, it reminded me of how the gelflings’ blood was drained from their bodies in The Dark Crystal. Carrying a child is a trauma. I had to have two injections in my ass because it was a different blood type to me. I was extremely tired, weak, and sick because my body was overcompensating, giving all my nutrients away. My first doctor objected and the next six or seven appointments were a flurry between English and Português . . . Desculpe, eu não falo Português. Favor fale lentamente. Estou tentando.

When I was pregnant I read about the forced sterilisation of women in Puerto Rico between 1936 and 1968. The United States government justified it by citing rising rates of poverty and unemployment. In Meehan Crist’s essay ‘Is it okay to have a child?’ she takes to task the notion of population control as a means for countering anthropomorphic climate change by intersecting it with colonial histories. Crist critiques Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, in which Haraway suggests the increase in global population expected over the twenty-first century will ‘make demands that cannot be borne without immense damage to human and nonhuman beings’, and argues for ‘personal, intimate decisions to make flourishing and generous lives . . . without making more babies’. It would be irresponsible to not consider the violence such a utopia would require.

I kept the ultrasound of my empty womb and thought about my friend who had to have her insides scraped out after a bad miscarriage.

The only way out is through.

III

My two favourite shows as a child were Buffy the Vampire Slayer and Veronica Mars. Both were blonde and American. The ideal. Buffy was a teenage girl navigating high school during the day, slaying vampires in the evening. Veronica Mars was a high school student during the day and a private investigator by night. Following the stars with my iPhone app, like my tuupuna did across the Pacific, I would be a sailor. Or I could be a pirate, a clown, undercover FBI, a Josephine Baker-type spy, anything you want.

One aunty I never liked used to call me and my sister patupaiarehe or parahitiki, knowing full well we didn’t speak Maaori. A relative on my mother’s side once stated that one of my dad’s uncles was a ‘rough sort of Maaori’. I never truly felt like I was white or brown; always a spy never truly engrossed in either world. Not white enough or brown enough. Always wanting to feel like I was enough.

Whenever I try and speak Maaori I always struggle to say my ‘t’s with a soft almost-‘d’ sound. You can hear my alienness even if these words on my tongue still lash out in defiance.

Now when I think about being called parahitiki I smile, thinking about my poi made with plastic bags. I’m an urban Maaori, constantly switching and hiding and being ‘adaptable.’ My skin tone fluctuates, but it’s always a point of tension and pain. When people tell me I should just go home it’s hard to explain that I’ve never felt at home anywhere except when I’m swimming in the ocean.

IV

We are the descendants of our strongest ancestors.

Maaori women, with the exception of slaves (male and female), were never regarded as possessions and retained their own names upon marriage so their whakapapa was never disregarded or taken from their children.5

I have so many rivers and mountains.

You are never alone because your whanau holds you, even when you are scattered across places (Lisboa, Riyadh, Ootepoti, Taamaki Makaurau) or no longer around. It’s the fact that the word in Maaori for father, matua, does not necessarily mean the singular father, but speaks instead to all Maaori men. That whaea denotes all Maaori women. In traditional Maaori society we were raised by our communities and certain work was not relegated by gender. Generations of knowledge flowed together seamlessly.

How do we now stand together again?

The only way out is through.

V

If we want to be truly liberated there needs to be a way in which to come together and account for the differences in our experiences and privilege.

I live in a predominantly black and brown neighbourhood in Lisboa. It is a community of people who have come from former Portuguese colonies like Goa, Macau, Angola, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissou, and Mozambique, as well as many Romani people who aren’t allowed to enter any spaces guarded by frog statues. It’s an area that is constantly under threat since the 2008 financial crisis and the Portugese government’s subsequent austerity measures (the harshest only abandoned in 2016). This did little to slow the consequences from the boom of tourism, Airbnbs, Lime scooters, and bodies like mine, all making it increasingly expensive to live here. I would never claim to understand experiences of otherness, racism, discrimination that are not my own. I despise the identification many Maaori and other non-black bodies take with black experience and black culture. I feel numbing discomfort at the thought of not giving back to what I’m taking from.

If we want to be truly liberated there needs to be a way in which to come together and account for the differences in our experiences and privilege.

I always think about being mistaken for being Aboriginal in Australia and a girl named Kara, who would make jokes about lynching me. I feel sick to think about the layers of racism being espoused from the mouth of a nine-year-old. It was so common for these kinds of things to be said, but at nine years old I did not have the language to reply. Histories become distorted and entwined, children are taught to hate and fear and to believe that their whiteness affords them superiority.

If we want to be truly liberated there needs to be a way in which to come together and account for the differences in our experiences and privilege.

In Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, Hannah Arendt – a Jewish philosopher who had fled Nazi Germany – offers her reports on Nazi Adolf Eichmann’s trial in 1961 for the New Yorker. Throughout the trial, Arendt became more and more concerned not by the idea that Eichmann was somehow a monster, but that his evil lay in his thoughtlessness, his impotence, the banality of evil he saw around him. During the trial Eichmann attempted to outline his reliance on a Kantian categorical imperative of carrying out the ‘law.’ But when he was carrying out orders related to the Final Solution it was as though he was no longer able to see reason, or right or wrong, or change anything. He was a ‘thoughtless’ actor in something he had ‘no control’ over. ‘He did his “duty” . . . he not only obeyed “orders”, he also obeyed “the law”.’

If we want to be truly liberated there needs to be a way in which to come together and account for the differences in our experiences and privilege.

We must work through this impotence or thoughtlessness if we are to imagine a future for ourselves. Without a sustained effort at a remembrance marked by nuance, we cannot learn to live with ghosts and so cannot think.6 There is much to mourn, but mourning is an action. By dwelling on loss we must appreciate how the world has and can change and how ‘we must ourselves change and renew our relationships if we are to move forward from here.’

Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi describes impotence as the ‘effect of the total potency of power when it becomes independent from human will, decision and government’. My generation is drowning in student debt, unable to buy homes, poisoned by our atmosphere and waterways, and unable to find meaningful stable jobs. We are watching the planet slowly being depleted of all its resources. We grew up knowing the assumption of infinite growth is a farce. We will work more hours per week than our grandparents did, live shorter lives, and face a multitude of crises that could mean the end of it all. We are marred by political flabbiness, apathy, and even nihilism. We have been watching the fires burning helplessly. I feel shattered trying to simply exist within this constant precarity.

Our bodies are exhausted. Our planet is exhausted. I feel lost trying to figure out what to do besides disappear. I want to hide. The end of the world seems plural, but this also means that there is potential for multiple beginnings. Berardi advocates for solidarity and a rejection of subjectivism. Because friendship transforms – it enunciates change – and because the future is unwritten and does not contain a linear development – there is still possibility. We have the opportunity to come together – to share and recentre our relationships to the mauri of the world. To avoid catastrophe.

If we want to be truly liberated there needs to be a way in which to come together and account for the differences in our experiences and privilege.

I return to Franz Fanon’s descriptions to try and feel hope for a future based around collectivity:

Individualism is the first to disappear. The native intellectual had learnt from his masters that the individual ought to express himself fully. The colonialist bourgeoisie had hammered into the native’s mind the idea of a society of individuals where each person shuts himself up in his own subjectivity, and whose only wealth is individual thought. Now the native who has the opportunity to return to the people during the struggle for freedom will discover the falseness of this theory. The very forms of organization of the struggle will suggest to him a different vocabulary.

If we want to be truly liberated there needs to be a way in which to come together and account for the differences in our experiences and privilege.

VI

Every day I am learning to understand my own history and culture by comparing it to others. Every day I am able to contribute something from my own heritage because it’s marked in my bones. If I stand tall enough with my back straight and with my head strong, leaning up into the warmth of Tamanuiteraa, my tuupuna will stand with me just as tall, keeping me upright when I want to crumble into defeat. I hold them in my body and I continue to carry them forward. I feel fear – the same loving fear for future generations that they must have felt for me.7 I know I must be resilient no matter the difficulty. My body being here is proof of their strength, even if I don’t feel very strong right now.

The sly smile ur lips make when you say the first

Tina!

before screaming

Huia e! Taaiki e!

When we introduce ourselves as Maaori we mention a river/sea, mountain, or long-deceased relative, as well as an entire tribe. All beings and objects contain a mauri or mana and are thereby interconnected. It’s not a ‘thingness’ or ‘plant-thinking’; it’s a constant awareness and relationship to the non-human – a relation that respects and manaaki all non-human entities. It’s impossible to explain how vastly our bodies relate to the world – they encompass soil, air, water, corpses, and even worms. Our bodies are the rhizomes, they are dynamic and beat softly in time with the rhythms of this world, because they are connected.

The only way out is through.

Please note that this essay uses Te Reo spelling and dialect from Waikato/Tainui.

1 Te Kawehau Hoskins and Alison Jones, ‘Non Human Others and Kaupapa Maori Research,’ Critical Conversations in Kaupapa Maori. Huia Publishers: Wellington, 2017, 56.

2 Andreas Malm, The Progress of this Storm: Nature and Society in a Warming World. Verso: London, 2020, 49.

3 Franz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press: New York, 1968, 37.

4 Brenna Bhandar, Colonial lives of property: Law, Land and Racial Regimes of Ownership. Duke University Press: Durham, NC, 2018, 74.

5 Rangimarie Mihomiho Rose Pere, ‘To us the dreamers are important’ in Mana Wahine Reader A Collection of Writings 1987–1998, Volume 1, ed. Leonie Pihama, Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Naomi Simmonds, Joeliee Seed-Pihama, and Kirsten Gabel. Te Kotahi Research Institute, 2019, 7.

6 Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press: Durham, NC, 2016, 142.

7 Günther Anders, ‘Thesis for an Atomic Age,’ The Massachusetts Review 3, no. 3, March 1962, 498.

Photograph © Kirk K

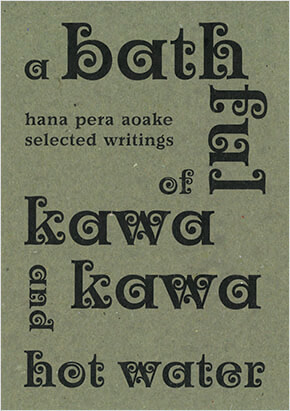

This essay by Hana Pera Aoake is forthcoming in A Bathful of Kawakawa and Hot Water, available from Compound Press.