The Male Hearth

Ayşegül Savaş & Bekir Ormancı

Early morning, a coppersmith’s apprentice walks down a bazaar alleyway in Kahramanmaraş, with an enormous basin hooked playfully on his head. To one side, three men stand watching the young boy, amused. A fourth reads his newspaper on a stool, accustomed to the sight, or ambivalent to it; perhaps he is annoyed by the fuss. It isn’t clear whether the photographer has chanced upon this cheerful moment or whether this is a show put on for his sake. But even if all this is staged for a stranger passing by, the ease of the subjects with each other asserts another intimacy – that the boy is one of their own.

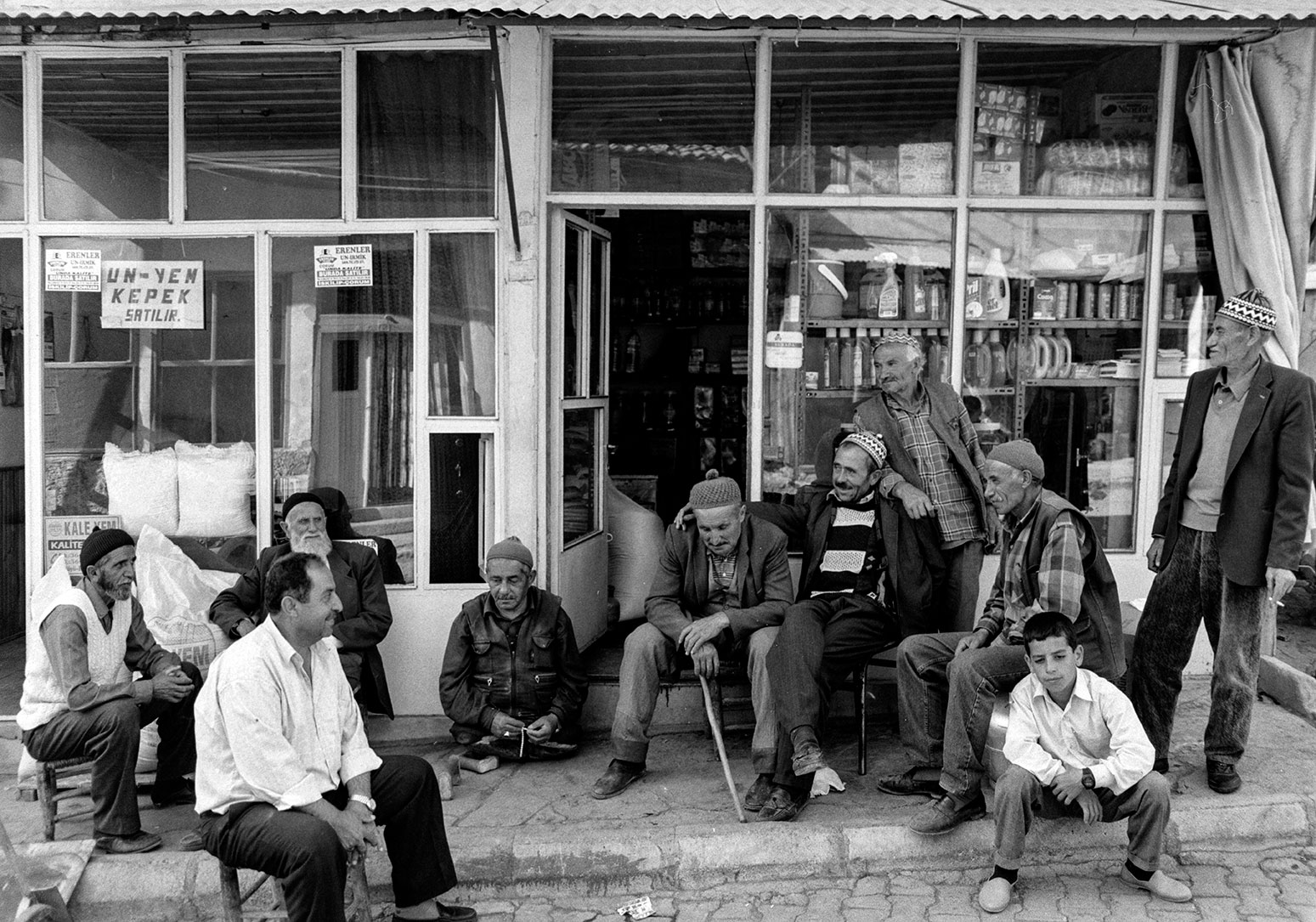

In the hilltop town of İskilip a group of men is assembled in front of a convenience store. One of the men has no legs. He is sitting on the ground, holding rosary beads. Some are laughing; they lean into each other, put their arms around one another’s shoulders. Here again is that same ease, the way children will spontaneously throw one arm around their best friends’ necks for a picture. And though this photograph is certainly posed, the fluency of their embrace suggests a familiarity beyond the performance.

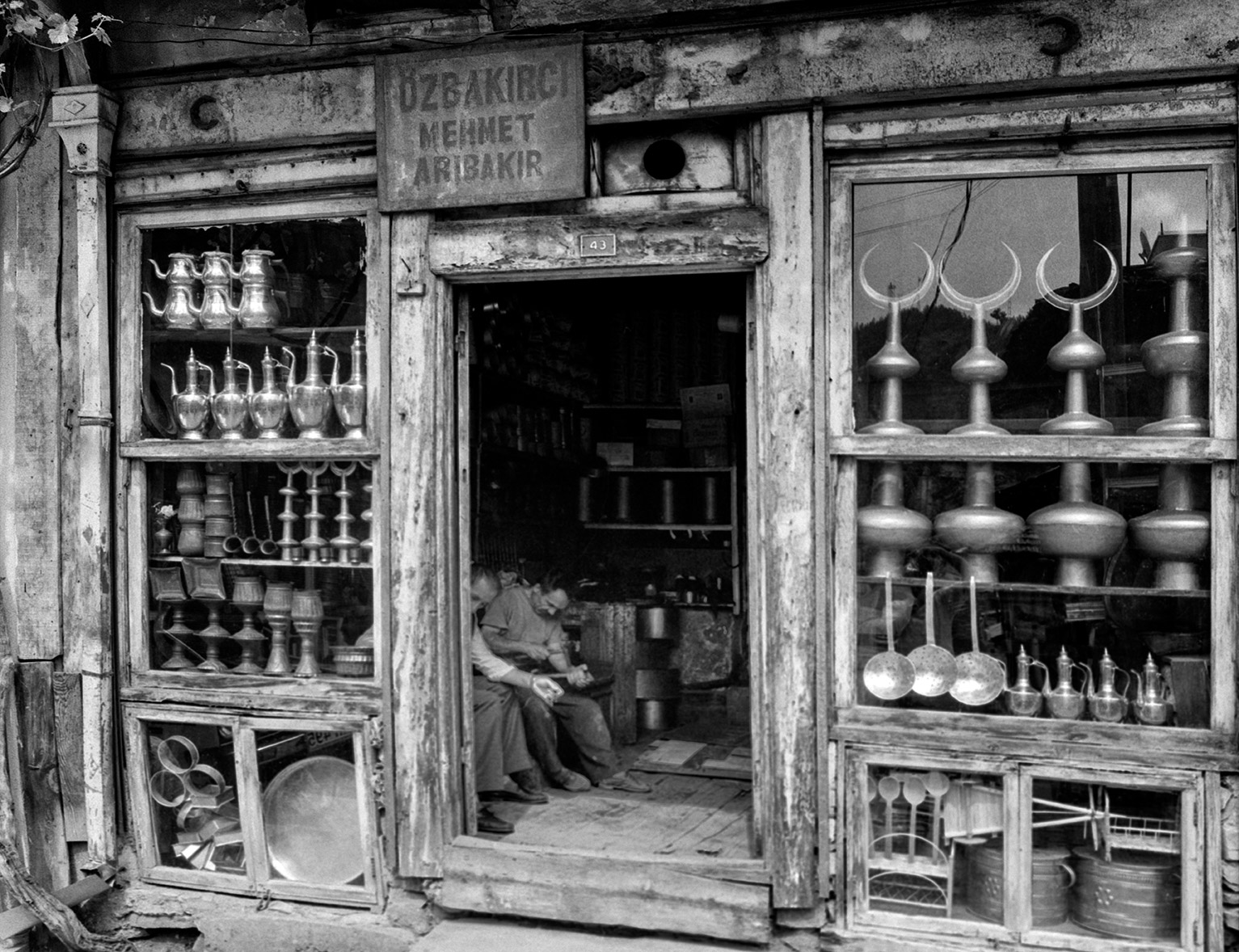

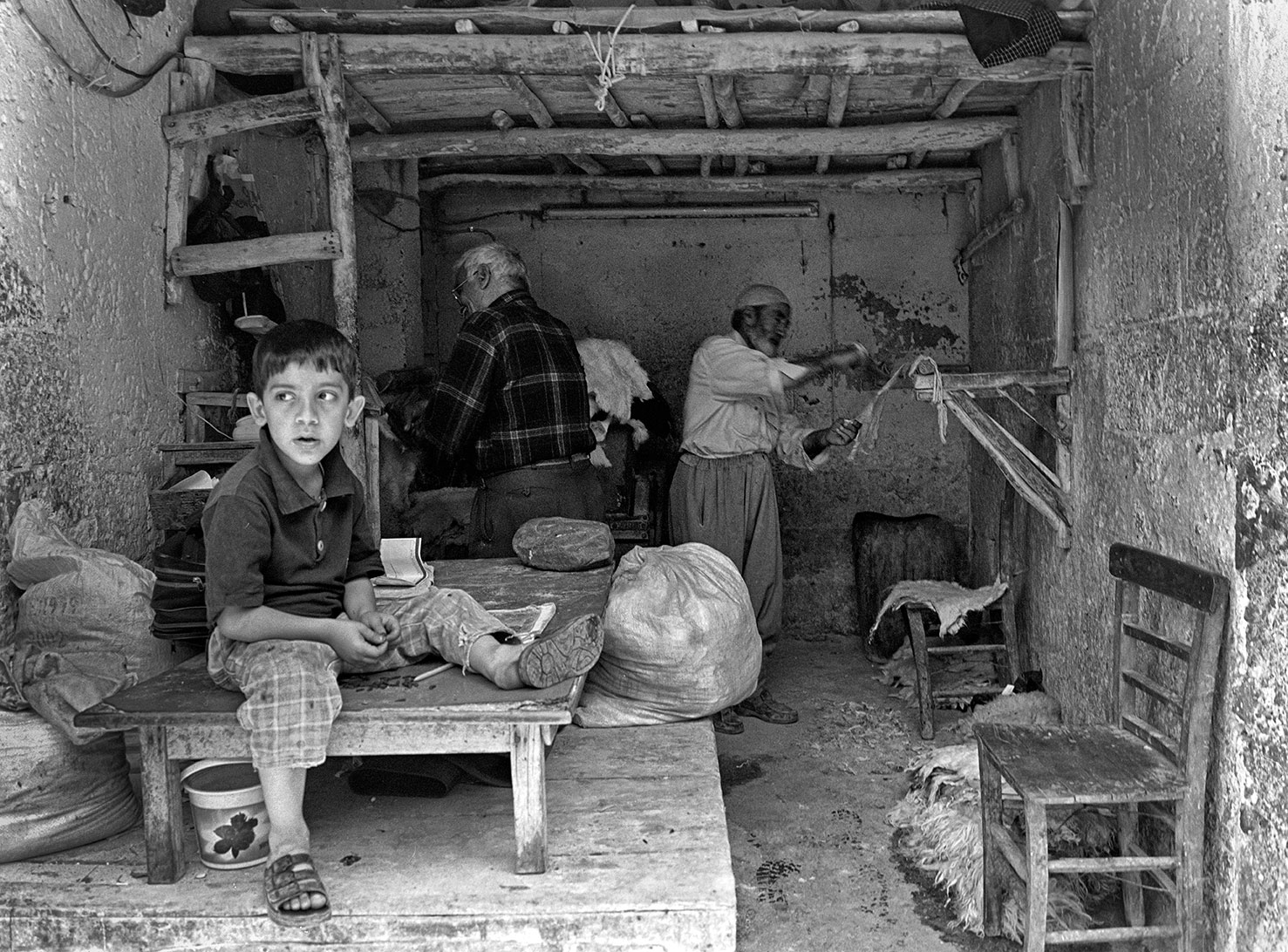

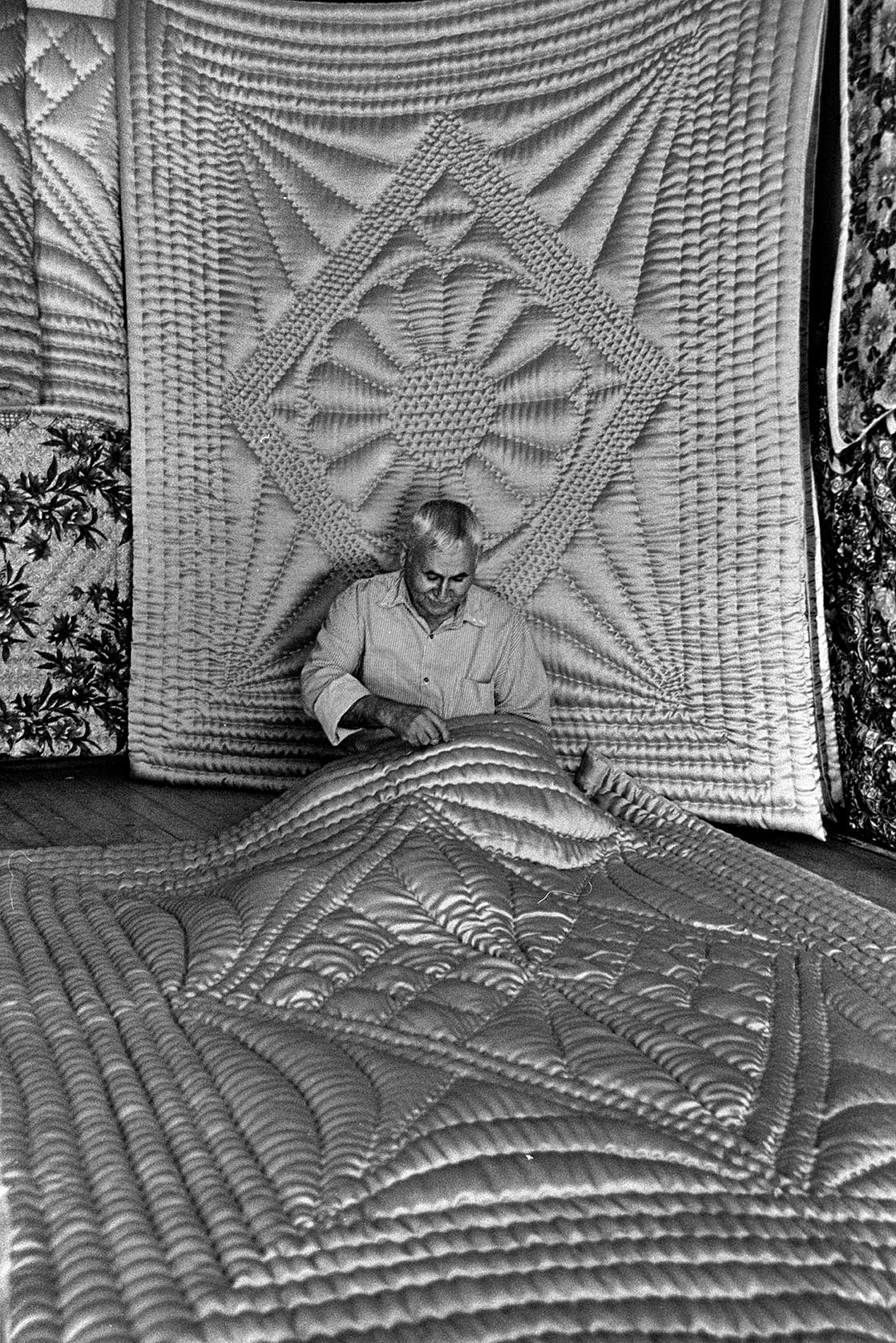

Bekir Ormancı’s photographs are of intimate public spaces: bakeries and barbers, the workshops of coppersmiths, cobblers, saddlemakers. On their walls are family portraits and calendars. In one picture, a child sits idly at the doorstep of a tanner’s workshop. Behind him, two men – the child’s father, uncles, neighbors? – carry on with their work. In another, a weaver’s apprentice looks up from his sweeping, while the master sits at the loom, beyond clouds of wool. A quilter, swaddled in luxurious fabric, stitches a traditional silk duvet that will constitute the essential component of a young girl’s dowry. An old baker stands in the domed shrine of his oven. In these miniature worlds lined with goods, filled with the tools and residues of labor, we experience the enclosure of hearths; of a unique domesticity within exclusively male spheres.

*

The first photograph by Bekir Ormancı that I saw, and the only one of his work I knew of for many years, was of my grandfather. He is sitting, shirtless, on a rocky beach. The stipple of orange and yellow rocks echoes the warm colors of his skin. Flecks of black are still visible in his thick moustache, like the dark lines of moss clutching to the stones behind him. His head is tilted, eyes squint to a smile. It is, to me, a picture of my grandfather’s mysterious age – revealing itself in the photograph’s dense textures, and defying it with his smile, the questioning tilt of his head.

For many years, the photograph hung in my father’s office. I remember that there was an ongoing joke about it – that it was inappropriate, somehow, or not very grand. A picture of an old man, naked. I remember someone saying, ‘Bekir, is this the best you could manage?’

Born in 1960, Bekir Ormancı is one of my father’s three best friends from boarding school in Istanbul. He is often the recipient of jokes, delivered in the hilarious language of their friendship. Sometimes, the friends share memories of their school years, showing off their intimacy to outsiders. More frequently, though, they talk to each other in the impenetrable language full of inside jokes, references, comedic voices and personas that they alone are privy to.

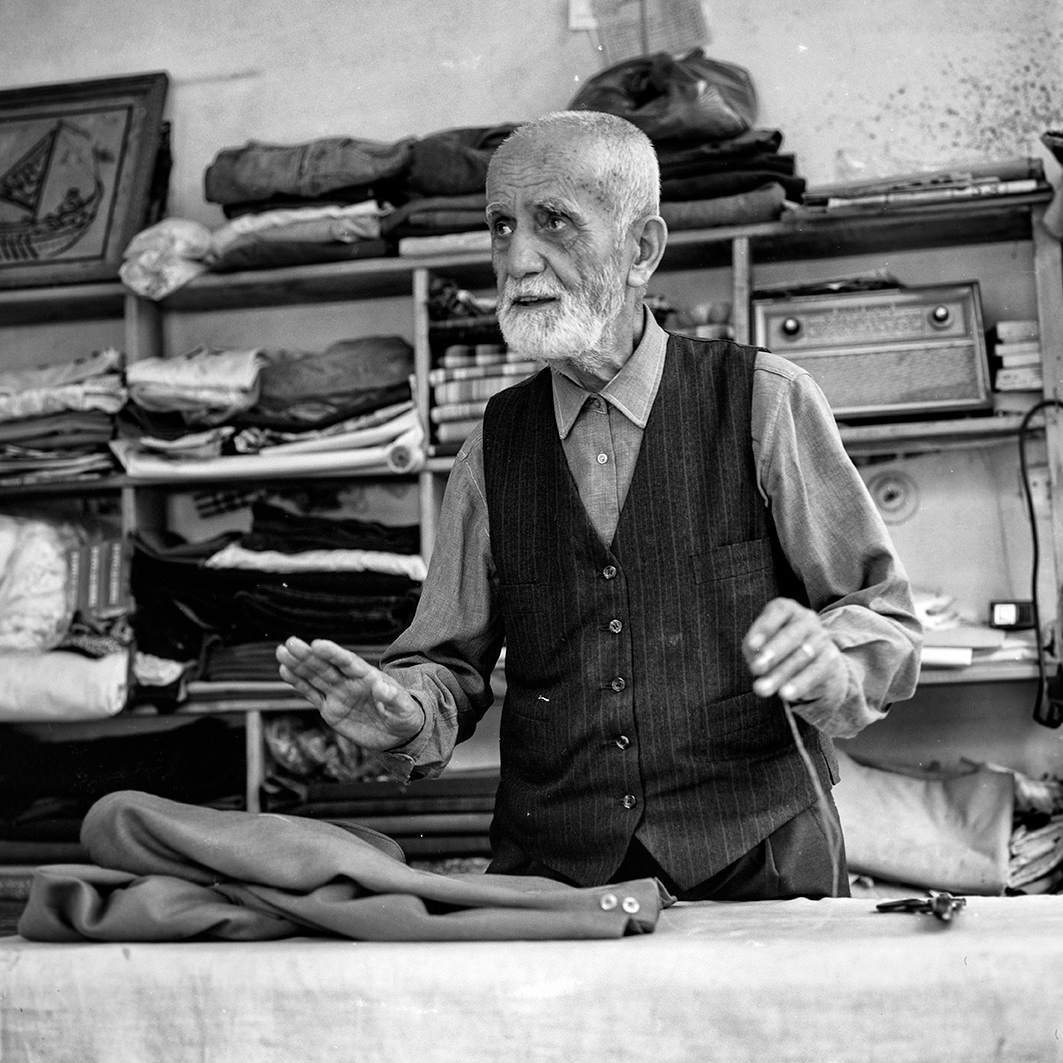

It wasn’t until several years ago when I saw his startling portrait of a spoonmaker in Konya that I asked Ormancı, whom I’ve known my whole life, whether he had more pictures of Turkish craftsmen. In the following years, he retrieved hundreds of photographs from his archives – a map of Turkey made up of its artisans, crafts and workshops – diligently recorded and modestly stored away in the time left from his full-time job as a glass manufacturer.

All of these photographs were taken in the late 1990s and 2000s. They are not records of a lost world – of then vs now – but the remains of an old order persisting here and there amid Turkey’s final stages of industrialization. They are taken at the narrow thresholds that separate artisans from unskilled workers; simple workshops from factories; neighborhood communities from a faceless urbanization.

The 1998 photograph of the barber in Ankara’s Beypazarı province, with a box camera behind him, might be one of the last examples of barbers who, at one time, were also portrait photographers. The old man is standing amid family photographs. Behind him, there is a stove with a tin kettle. His proud, frail expression delivers the pang that with him, this world will also vanish.

The ache of loss is also in the objects themselves: the straw brooms, saddles, beads and bells for horses and donkeys, felt cloths to make shepherds’ vests, documented in the last moments when there is still real use for them.

Whenever he’d send me photographs, Ormancı would sometimes include a note. ‘You might not remember these . . .’ or, ‘I don’t think you would ever have seen such a workshop.’ Some of the notes are for my own education, full of delight in showing me ways of life I may never encounter. ‘My dear daughter, what is a külek?’ he writes, unprompted. ‘In my childhood, these wooden containers were used to store honey, molasses, clotted cream . . .’

Others are more likely to soothe his own yearning. ‘Who knows how many of these are left?’ is the note accompanying a series of photographs taken one afternoon in a tack shop: two men have dropped in to chat and have tea; they sit squeezed on a narrow bench while the owner stands at his work table, immersed in his repair.

Next to a portrait of a saddlemaker he notes, ‘I hardly see saddlemakers these days.’ And later, ‘May God grant them long life but I don’t know if these two are even alive now.’

In other notes, when I’ve pressed him for an ‘explanation’, eager to read the photographs with a clear purpose (‘Do you think you’ve captured a softer face of a patriarchal society? Are these private moments when men put aside their stern social personas?’) he is evasive, not keen to make a judgement: ‘I GET BORED WRITING ABOUT THIS STUFF!’ Another time: ‘Those are the faces of our Anatolian people for you. Modest, respectful.’

His impatience with abstractions and his love for the people of Anatolia is evident in the careful documentation of tools, in the poetry of worn-out spaces, the serene concentration of the craftsmen, and the capacious time radiating from the pictures’ composition.

Since 1980, Ormancı has taken photographs around the world and across all of Turkey. The common denominator of his work, he says, has always been human relations. He wants to explore ‘the ‘lifeline’ that humans form with their environment and with their work, and to capture the inner peace that arises from this connection.’

*

To examine a photograph is often to form a story that links the visible world within the frame to the invisible one outside it. In Ormancı’s pictures, there is the invisible hand of modernization pressing against the frame. There is also the absence of women and girls. These are entirely male settings, often with the framed photograph of Atatürk, the ‘father’ of the Turkish Republic, looking down from a wall, alongside other family portraits. The shop names – ‘True Coppersmith Mehmet Arıbakır’ (bakır meaning copper) – are also testament to their patrilineality.

Ormancı himself joined his father’s work as a glassmaker early in his life. I once asked whether he regretted that he wasn’t a full-time photographer. He said, without resentment, that there’d been other expectations of him. He told me, chuckling, that his father once asked how much time he needed in order to take all the photographs that would keep him satisfied until the end of his life. Only then, his father said, could Bekir join his father and devote himself fully to the work.

*

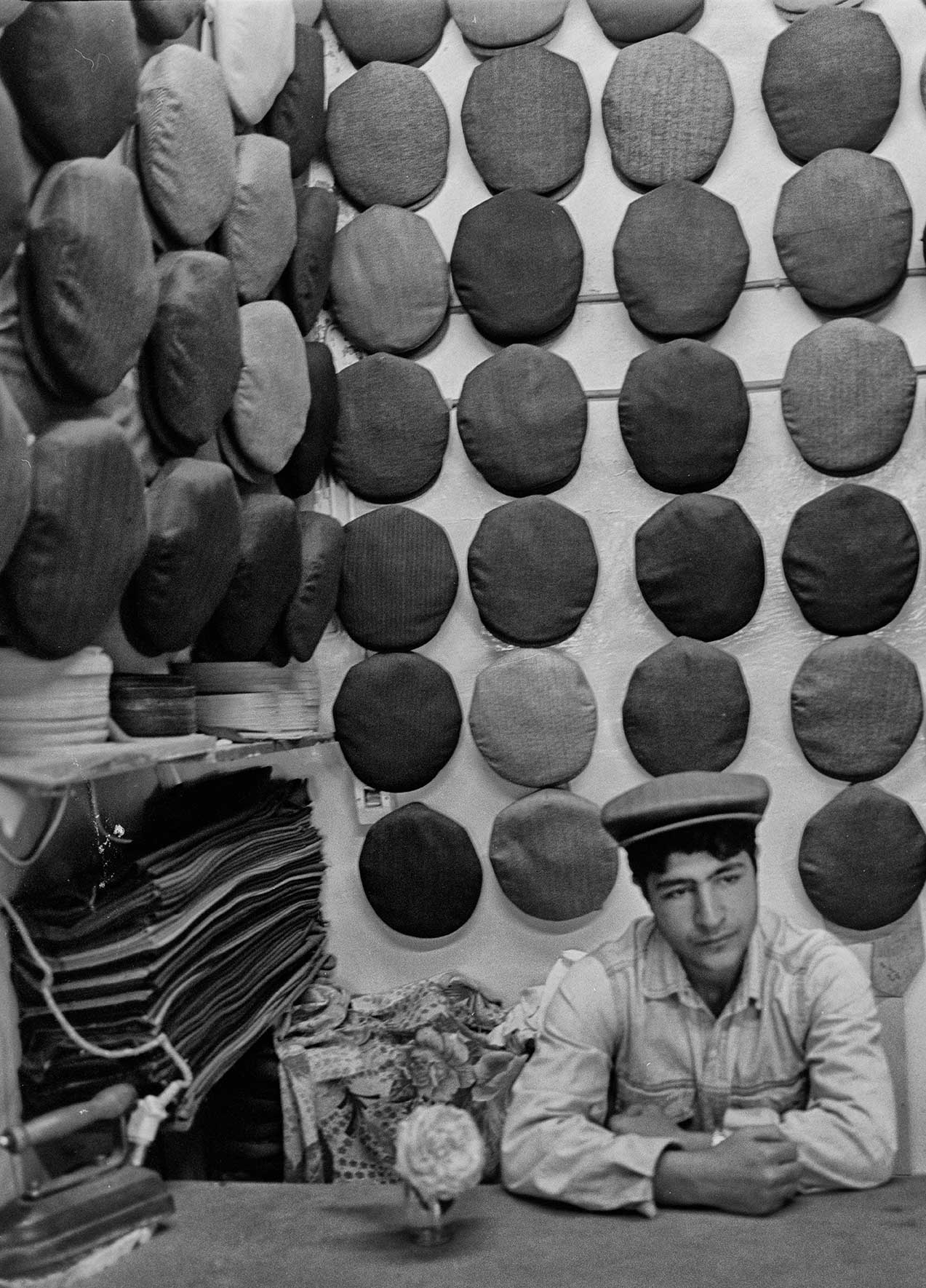

The photographs capture glimpses of unease alongside pictures of rootedness, especially in the faces of the youngest, not yet sure of their own place. In the same shopfront gathering at İskilip, a boy sits slightly apart from the group, looking all too stern for his age, as if this will fit him in with the grown men behind him. In a tailor’s shop, its back wall lined with peaked caps, an adolescent sits at a table, looking askance. It seems that he is trying to contain a painful transformation, trying to stay put. His face, blooming with the early shadow of a moustache, is as lush as the single rose beside him. His fists are clenched.

Other hands tell other stories, immediate and intimate – smoothing a cow’s hide, stitching leather, holding a cigarette or the shoulder of a friend. The photographs speak to our sense of touch through the textures of peeling walls, the piles of wool and folds of fabric, through mud-slicked palms and the cobble of neighborhood streets.

These are decidedly not abstractions, but the thing itself: here is the look of someone at his work, at home among all the nooks and crannies, the shelves of tools. These are the places where people continue a tangible existence. ‘Our soul is an abode,’ Gaston Bachelard writes in The Poetics of Space, ‘and by remembering “houses” and “rooms,” we learn to “abide” within ourselves.’

*

When I was in high school, Bekir Ormancı took me to the Hayyam passage in Istanbul, to fix my father’s Canon A-1 camera. That summer, I joined a group of friends to volunteer at a village school in Van, on the Iranian border. I came back from the trip with rolls and rolls of photographs. My friends and I had spent most of our time at the dormitories and adjacent school, where we lived and taught. The few times we visited homes, we were ushered in separately to men’s and women’s quarters. Where the families spoke only Kurdish – which none of us understood – we sipped our teas in silence, smiling at our hosts.

My photographs were mostly close-ups of children’s faces huddled together outside the dormitory, sticking out their tongues, smiling broadly, or looking wide-eyed. The closeness of the camera may have been an attempt to compensate for the lack of any profound glimpse into the social and private life of the village. The pictures had neither context nor composition; they could have been taken in any corner of the world.

I showed my photographs to Bekir Ormancı and watched with dismay as he flipped through them silently. He finally paused at one of a shepherd boy, whom I’d followed one sunrise with my friend to an adjacent village. He had walked ahead of us with his cows, then stopped and turned his head to look back, with a strange expression of hope and skepticism amid a field of poppies.

‘This is your only photograph,’ Bekir Ormancı told me. ‘You can throw the rest away.’

He went on to explain that this one alone told a story.

*

In his memoir Five Cities, Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar, the great novelist of Turkish modernity, with its many contradictions, writes of a morning in Uludağ mountain, when he listened to the sound of a shepherd’s flute woven into the calls of sheep and lambs. ‘I’d known that Turkish poetry and Turkish music are journeys in homesickness,’ Tanpınar writes, ‘but I hadn’t realized how inseparably they are tied to this aspect of our life.’

‘This aspect’ is perhaps the primal longing for home at the source of Ormancı’s work – the invisible shroud of the past tugging at the present. It is the double illumination of his photographs, revealing all that survives, at the same time stating what is lost.

All photographs © Bekir Ormancı