The phone rings. I equate the ringing with bad news, all the more when it’s at an off-hour.

As much as some might say I live in full embrace of life, they are wrong. I live in fear of life being interrupted, of the shoe falling, or something disastrous threatening what perch I have. I talk a good game about living in the moment, but then I hold my breath. I live dreading the next thing that will level me, that I will have to climb back from. I live aware that it could come at any moment from any direction. I live under threat.

The phone rings. I am not a phone person, which means I don’t even know where the phone is. I rush from room to room looking, remembering only the phone that hung on the kitchen wall in my parents’ house, the long curly cord, the heavy receiver you held in your hand and which, if inclined, you could slam down on a hook with great satisfaction.

The phone rings again. I have four rings before the machine picks up, the machine that replaced the old machine, the old machine that had a cassette so you could save your messages like a time capsule – top hits from the early 2000s; ‘Hello, it’s Lou [Reed]. Do you want to go see a play with Angela Lansbury? I know you do. Tonight.’

At the end of the third ring I find the phone, tucked into a bookcase. The name on the caller ID is both familiar and unexpected. I am loath to answer, but can’t ignore it. It is not the shoe falling, but the sneaker has come untied.

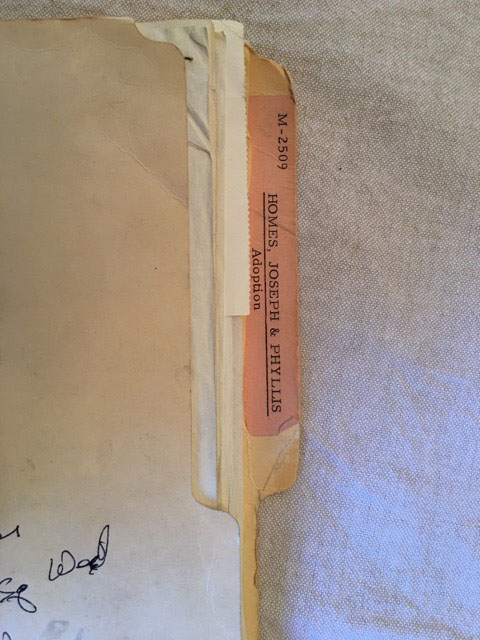

The caller is the son of the attorney who handled my adoption fifty-five years ago. Ten years ago, after his father died, I phoned to ask if he might be able to locate my adoption file. Now he is calling to tell me that he’s found the file.

All of this goes back to December 1992, my thirty-first birthday when, out of the blue, my biological mother contacted the attorney and asked if I might be in touch with her. The attorney contacted my adoptive parents who waited until I came home for Christmas to share the news.

In 2007 I wrote a memoir about the experience, The Mistress’s Daughter, which had its own interesting set of side effects.

The randomness with which my biological mother suddenly contacted the attorney has never escaped me – it was a bit like I was a package or a coat she’d absentmindedly left behind thirty-one years before. She had returned fully expecting it to be there, waiting, in stopped time.

I now understand more about the nature of stopped or fractured time, how fragments or experiences can remain trapped in a moment long passed, how trauma can freeze an entire life and how time itself can suspend, conflate, blur, so that it can be solid, liquid, gas all in one day and then back again. Even for those of us who feel we have integrated our history, there can be fragments, like shrapnel, that push to the surface without warning.

The son of the attorney is talking to me and I am trying to remember what I know about him: he’s a young man interested in politics. At the same time I know that he must be older than me, but my awareness of him is in stopped time. At this very moment he’s explaining that his mother recently died and they were cleaning out the house, and that’s how he happened to find my file. He called the number his father had written down as mine in 1992. A creature of horrible habit, I have lived in three places in fifty-five years: my parents’ home, a small apartment in the West Village and now a larger apartment four blocks away. I have had the same phone number for more than thirty years.

As we’re finishing up, I say, ‘I remember you were interested in politics?’ Without a beat or a guffaw, he says, ‘I’m the Attorney General for the State.’ And I am, again, smacked by the nonlinear nature of fractured time. I hear myself saying, I remember you were interested in politics and feel like someone’s grandmother. I thank him, truly touched that he’d remembered my interest in the file and that in the midst of all else he made the effort to contact me. When we are off the phone, I look him up and see that he is seventy years old.

I remember my parents talking about his father, the attorney, with deep admiration, respect and gratitude. I met him only once. I’d gone with my parents to an exhibition of work by George Nakashima, the Japanese-American woodworker who had made many things for my family – among them my grandmother’s dining-room table, which is now mine, and a high chair for me.

‘Is this Amy?’ a gentleman had asked. From the way my parents responded, it was clear this was a momentous occasion. Before anything else was said, I had a flash of psychological confusion, or conflation – perhaps he is my father? But no, he was a path to my father. As a child I had similar feelings about our family pediatrician, Sydney Ross, who had taken care of Bruce, my mother’s first child from an earlier marriage, later adopted by my father, who had died after a long struggle with renal failure when he was nine. The doctor was a patrician Boston native, a Harvard graduate who wore bow ties and spoke in wonderfully low and measured tones. Without knowing exactly why, I was drawn to these wise men – they knew something more about me, something that others didn’t. As I am writing this, I remember that the pediatrician was the first person from ‘our side’ who saw me. Just after I was born he went to the hospital to examine me and phoned my mother to say, ‘She’s perfect but at some future point she’ll need braces on her teeth.’

All that I’ve ever known and all that I never knew. The envelope takes several days to arrive and when it does I put it in my office and let it rest. I leave the envelope for weeks, having already once had the terra firma of identity slip out from under me like sand followed by a long, slow climb back to safety – I am aware that once I expose whatever is inside I will have to deal with it. I am not in a hurry.

There is the fear that there might be something in the file, a surprise that changes the narrative as I know it. And if I were to ask my ninety-year-old mother, whose memory has begun to slip and skip like a scratched record, to go back and retrace the events, she’ll think hard, get frustrated and say, ‘I just don’t remember.’

What do I need in order to open it? Safety, the impossible assurance that I will not come undone.

And then on a day as random as any, I’m ready. I’m home alone. Knowing I have some time, I rip open the Tyvek mailing pouch.

There is an unexpected uptick of my heart. The folder itself registers as beautiful. The manila has turned a slightly more golden hue, but it has aged without showing signs of wear. It has the smell of confinement, of years, of history. Fifty-five years old and, for the most part, untouched – in some ways this folder seems like a distilled version of me. It is the core of me, the facts of me, the narrative of my life that started before my own version. For fifty-five years it lived first in the attorney’s office and then in his home – in that way I have lived with him for longer than I lived with my family.

Before I open it I can see what’s inside: tissue-thin typing paper – cockle finish onion skin – that is what was used with carbon paper before everyone had a copy machine or scanner at home. There is a translucency to the paper that reminds me of mother of pearl, I don’t know why.

I open the file. There are thin metal binding brackets on both the left and right sides holding the documents. I start on the right: on top, a single sheet of yellow legal paper that has lost color over time. The attorney’s notes, written in a kind of code, small precise marks, with dates. T/C means telephone call, with dates and notes – left message, will call back. His notes are very much like those of the pediatrician, who wrote similarly on index cards in compact coded script.

On the top sheet, which is from 1992, the attorney has written down HER name. On the night when my parents told me that my biological mother was looking for me, my mother said, ‘Do you want to know HER name?’ Reflexively I said, ‘No.’ Later that night my mother came back into my room and, as though to soften me up, said, ‘She has the same name as one of your friends,’ and I said, ‘Well you can write it down and put it over there.’ I wasn’t ready.

Am I ready now? The attorney has written HER name, and HER brother’s name (he was a local attorney). There are two other names that are vaguely familiar and the name of the doctor who delivered me. This one I remember immediately because it was on my amended birth certificate – I always wondered if that was the doctor’s ‘real’ name and had fantasies of contacting him to ask: who is my biological mother?

Despite my concerns about my ninety-year-old mother’s memory, I immediately call her to ask if she knows who the other two – a married couple – are. The surety of her ‘no’ trips a switch for me and I recall that they were the friends of my biological mother’s who helped her arrange for my adoption.

On book tour for the memoir in 2007, many people shared their adoption experiences with me, stories of the child they surrendered, and their desire to search (or not). One, which stayed with me, was from an elderly man who told me that his eighty-year-old wife very much wanted to find her birth family and could I tell him how to do it? Even now, in most states and countries, an adoptee doesn’t have the right to know who they are and how they came into the world. The laws vary from place to place, and were mostly designed to protect the privacy of the often-unwed mother, and the often-infertile adopting couple, rather than the needs of the child.

As I am connecting the dots I feel another skip in time. Washington DC in 1961 was still a small southern town – people knew each other, and there was a mildness to the way business was transacted. The language of these legal documents is not ornate or excessive – nothing like the forty-page contracts I sign to sell a novel or a television show. And yet it is an agreement, and in this case it is specifically for the transfer of a white infant with a Catholic mother to a Jewish family. The specificity and repeats throughout the document of the racial and religious information are interesting. Do they speak to the time it was written or the need to find a way of describing the goods?

When I was writing the memoir, the question of religion came up often. My biological mother was Catholic, but identified as Jewish. My biological father, whose father was Jewish, had a Catholic mother. I spoke with his extended family who said it was a big deal if someone in the family married a Christian who wasn’t Catholic – and that they knew of no Jews in the family.

And again, in the midst of writing this, without even realizing what I am doing, I am plunged down the rabbit hole of the internet. On the right side of the paper – on the top line – is my biological father’s last name, followed by an arrow and the name of a lawyer in Washington DC. When I finally met my biological mother in 1993, she told me a story of going to meet with my biological father’s lawyer while she was pregnant and the lawyer telling her, ‘There are only so many slices of the pie,’ meaning that my father had limited resources and they had to go around. Her response: ‘I’m not a piece of pie.’ And she walked out of his office.

I google this lawyer. In the decade since I first did my research the web has grown exponentially. I find myself looking up each of the names on the page. Hours are lost. I go deeper and deeper. As I’m hunting I discover how much of what I uncovered ten years ago I’ve forgotten. Not only have I forgotten what I once knew, I also find the fact that I’ve forgotten uplifting; it tells me my identity is firm and not suffering from the forgotten or the unknown. Still, I feel compelled to piece my history back together, and it takes days – there are fresh clues: breadcrumbs, photographs, documents. This time I find a photograph of my great-grandparents on my father’s side.

I’m still on the first page, which has a court order for a waiver of investigation of the adoption. The bottom line of the petition to waive reads: ‘The Infant child has been with the Petitioners since birth and no parental consents are obtainable.’

A new fact, a narrative detail, is revealed in the petition: I was delivered to the care and custody of my adoptive parents on 22 December 1961. My adoptive mother used to tell me the story of driving downtown in a snowstorm to pick me up. Forty years later, I find out that my parents had the next-door neighbor in the car with them. The neighbor was the one who went into the hospital, met my mother and dressed me in my going-home clothes.

Now, with the internet being what it is, I can look up the weather on the fabled day, 22 December 1961. The weather is recorded as drizzle – less dramatic, and less romantic, than snow. Was the storm that my mother has always described real? Or was it like a snow globe? An emotional snowstorm, a nostalgic remembrance? I ask and she absolutely insists that it snowed – and given that the temperature was in the low thirties and that there was precipitation, it’s not impossible. I tell her that I believe her and I do because that part of the story has never shifted.

With a nifty online pregnancy calculator I figure that I was conceived on 27 March 1961. Does that fit with what my biological father told me about my mother telling him the news that she was pregnant on the day that his mother died – 11 April 1961? Would she have known that soon? And did she know then that his wife was also pregnant? In 1993, when I met my biological father, I learned that he had four other children, one of them a boy just a few months older than me who, oddly enough, was working for a local bookseller.

The next item is a note in my adoptive mother’s handwriting: her beautiful Palmer Method script. ‘Here is the balance owing on the adoption litigation. Many thanks.’ The attorney has clocked the amount: $137.80. The other side of the card again catches me; it is the stationery I remember my mother using to write thank-you notes and condolence cards – white heavy stock with her name embossed in navy blue. I would bet there is still some of it left in her desk drawer.

There are a few more pages, yellow carbon copies of letters dated throughout November 1963. I am almost two years old. ‘Dear Mr and Mrs Homes, We have finally received the enclosed Certificate from The Department of Health,’ one letter states. Below is a copy of another letter, to the Circuit Court. ‘We have for several months been attempting to get a birth certificate for the child adopted . . .’

And then beneath that, a letter from the administrator of the hospital, the Children’s National in Washington DC, to the attorney, typed on crisp, white, headed paper. ‘Thank you so much for your letter of 25 March 1963. I regret to say that I am not too well acquainted with the Bruce Homes Fund since I did not assume my position as Administrator until after this fund was established . . .’

The letter goes on to say that donations were received in memory of Bruce Homes, the donors thanked, and that in the fall of 1962 – about a year after Bruce died – the hospital hired an expert in renal research. The funds were used to equip the laboratory and an office. There is a discussion of whether or not the Homes family would like a plaque in memory of Bruce, and that perhaps it would be better for the hospital to wait awhile before approaching them but they would very much like to have a plaque made and would appreciate the help of the family in formulating the wording.

Bruce died six months before I was born and I always thought of myself as the replacement child, but now, as a parent, I am deeply aware that there is no such thing. That said, occupying space once held for a nine-year-old boy had a huge impact on my own development as a child, as a girl and as a writer. The fact that this letter punctuates the middle of my file is a perfect illustration of the way his life and my life intersect.

Beneath the letter from the hospital administrator are copies of letters about my birth certificate and the sealing of the ‘package’. This is the original birth certificate and the final decree of the adoption. The package can be opened only by order of a court of competent jurisdiction. ‘Before we can proceed with the substitution of records it will be necessary that you forward the certified copy of the final decree. The certified copy must bear the signature of the clerk of the court and the impressed seal of the court.’

This is the kind of statement that as a teenager would have sent me over the edge with its legalese and the sense that any number of clerks and judges – people who had no knowledge of or interest in me – had power over me. ‘Upon receipt of this document and a fee of $3 we will proceed with the substitution of the records . . .’ The word substitution stuns me; is that what adoption is, a substitution? ‘. . . we will furnish you with a certificate which will show the adoptors to be the natural parents.’ It goes on to say you can also get wallet-sized ‘birth cards’ for $1, ‘all fees payable in advance’.

There is a note from the attorney to the court saying they’d hoped that the biological mother would sign the papers, but she has not and they do not know where she is, and she checked into the hospital under a false name. He asks the judge, therefore, to sign off on the adoption. And then another letter to the clerk from the attorney, saying that he’d spoken to the judge about this matter previously and while they’d expected that the natural mother would execute the releases sent to her, ‘We found that she registered in the hospital under a fictitious name and is totally un-locatable at this time.’

This all fits with what my mother told me long ago: that after my birth my biological mother had vanished without signing the adoption papers and that it took a year to get the judge to sign off on the adoption and that she was terrified to leave me alone with anyone except my father for fear someone could come and take me. Thirty-one years later when my biological mother did come and find me, she said, ‘If I’d known where you were I would have come and taken you away.’ Did she know that for much of my life she lived only a few minutes from my parents’ house? And that she was giving voice to my mother’s worst fear? As a child I was always afraid of the house being broken into. It was a glass house, very modern, exposed. At night people could drive by, see in and know exactly where we were as we moved from room to room. As a teenager, whenever I was home alone I barricaded myself into my room with furniture.

The last page, a single sheet of yellow legal paper, is a series of small notes running sideways down the paper in a row, a cryptogram.

Rm 27

Del 35

Rec 10

Lab 8.50

Med 15

Baby 7

Anaes 35

It takes me a minute to decipher. Rm = Room, Del = Delivery, Rec = Receiving? Lab = Laboratory, Med = Medicine, Baby = Me, Anaes = Anesthesia. But what are the numbers? And then it comes together: the figures are the costs of having a baby in 1961. At the bottom of the page there is a total and a note about a check being sent.

And then, underlined, the name Elizabeth Hecht. I stare at it. It’s familiar, but I can’t place it. I’m going to have to look that one up again. There’s an awkward sensation in my body, a kind of cellular dissembling, an emotional earthquake, and I realize it’s not someone else’s name – it’s my name. I am Elizabeth Hecht. That’s what she named me.

Add to that the oddity that my adoptive mother also wanted to name me Elizabeth, but when I came home wearing a bracelet that said ‘Elizabeth’ in tiny square letters, my mother immediately removed it.

She named me Amy, because it means friend, because it is simple and modern. Amy from Little Women – a book I have never been able to read. Amy.

I was never an Amy. I put my initials on the top right corner of my school papers, my homework. A.M.H. That is the name that gets published. When people write about me as Amy, they do it as if outing me, as if wanting to reveal that I am a woman. When people write about me as Amy, they’ve got it very wrong – in more ways than they know.

A.M. Homes. What kind of a name is that? People ask without realizing what a loaded question it is. ‘Are you trying to hide who you are? What’s your real name? What does it stand for? Wait, don’t tell me, I already know – Ann Marie?’ A.M. Homes is a brand name – like a kind of soup. Like Andy Warhol, you say it all at once. A.M. Homes, what does it mean? What does it stand for? A.M. Homes. Almost. Maybe.

I go back to the beginning of the file on the left-hand side – there are copies of the various petitions and copies of the investigation waiver finally signed by the judge. At the very bottom of the pile of papers is a small typed note, stapled to a document. The first time I go through the file I barely notice it – only on second glance do I read it. The phrasing reminds me of something, an awareness comes over me like a caul of confusion. I’m wondering what lawyer would have written this and then it is clear; it is a note written by my biological mother to the attorney.

Enclosed are the custody papers. These papers have been completed and signed, but have not been notarized as I find it impossible to find an individual that could be trusted never to reveal the contents of this.

I feel every precaution has been taken so far to protect everyone involved and by doing something like this would only destroy the protection extended to me and the other party in this matter.

Trusting you can arrange to have this matter taken care of.

I lift the small note up – my biological mother has filled out the release papers with the following information:

Elizabeth Hecht being duly sworn according to law deposes and says that she is of the white race, over twenty-one (21) years of age; that she is unmarried; that she is the mother of a Girl born at Washington DC on the 18th day of December 1961; that the name and address of the father of the said child are unknown.

Elizabeth Hecht. A moment of confusion; the peculiarity of seeing the name Elizabeth Hecht in two places; as both the mother and as the child. This conflation of who she was – she was herself and she was me. It reminds me of one of the few phone calls I had with her after she found me in 1992. She was angry about my reluctance to rush headlong into some kind of mother–daughter reunion/love affair with her.

Elizabeth. I am down the internet rabbit hole again, something nagging at me, something I found along the way: my biological great-grandmother’s middle name was Elizabeth. Looking through my biological father’s family tree I see generations of names, first and middle, repeating, echoing through the years. Did she know that my father’s grandmother’s middle name was Elizabeth? For thirty-one years, from my birth until she found me, my biological mother had held on to the fantasy, the promise of a better life, of a family, a husband. She told me the story of my biological father briefly leaving his wife and moving in with her and then going back to the wife. My biological mother responded by having him arrested for abandoning her. In 1993 her fantasy life remained strong; she suggests that we, the biological trio, have Thanksgiving together and that we have a family portrait painted. Knowing my biological father the little bit that I did, I can see how he would have made these promises with a part of him genuinely hoping he would be able to deliver, another part knowing it would never happen.

‘You should adopt me and take care of me’ is what she said to me over the phone in 1992.

Elizabeth Hecht, a young unwed mother, and Elizabeth Hecht, an infant in need of parents – she was both.

And where does it leave me?

I walk away. I go into my teenage daughter’s bedroom and begin carefully folding her clothes and putting them in drawers. I’m folding and thinking, when will she clean up her own room! I’m folding and laughing, filled with love and wonder that I have this bright, feisty child, very much her own person and at the same time equally of her father and me.

She moves through life as a young woman who knows herself, who is adventurous and open to new experiences. She jokes about what a planner I am, and how I am always prepared for everything, from gloves and hats to snakebite kits and clotting bandages. My child is equally on top of things but in less fraught ways, and she is enormously generous and kind.

I see how she craves family; she wishes there were more of us, more siblings, more aunts and uncles and cousins. I see how she longs to find herself in us and I also see how she is finding herself in the world. People ask me why I don’t write more about being a mother, about the experience of being adopted and now having a child of my own. I am saving it for her; she owns her experience of what it is to grow up with a ‘lost’ parent.

When my daughter gets angry with me she calls me Amy in a very stern tone, just as my mother once did. We have a running joke about how when I was a kid, my mother would open the front door and call out to the ready ears of all the children playing outside, ‘Amy, time to come home. Amy, your bath is ready.’ And after ignoring her for as long as I could, I would go home – both embarrassed and loved.

I think of my childhood, family weekends, going to art museums with my father, the inadvertent education of concerts and theater that my parents took me to when I was too anxious to be left alone. I see the person I have become, a mother, a writer who struggles to make sense of the world, a woman who teaches because she wants young men and women to see how wide open their options are, a person who does volunteer work in excess because she feels an obligation to improve things for others, a daughter with an aging parent in a distant city and an older brother who has struggles of his own. Despite the fifty-five years of rebellion, the youth spent feeling attached to no one, in mind, body, spirit and temperament, I love them deeply and in time have become one of them. Beneath that of course there is more – rivers complex and sometimes confusing. But at fifty-five I am myself, for better or worse. I look at the life first given to me by my biology and then by my adopted family – and I think I am lucky. Despite my biological mother’s narcissism, her fantasy of the life she wanted for herself, she knew she could not raise a child. I can only imagine the difficulty and grief of having to make that decision, and having to live with the strangeness of knowing that somewhere out there is the person you made. And for my adoptive mother, who lost a child, I can feel the difficulty, the joy and grief of having a new life delivered to you, the risk of loving that child, of attaching without the consent of the biological mother. She was heroic.

I hope my daughter becomes an integrated amalgam of all of these parents and their rich histories. I think of my own difficulty in forming an attachment to her when she was a baby and now I’m sure that what passes between us is a kind of biological knowing, a sameness that I’ve never experienced before. I look at her and she fills me with joy, comfort and the thrill of bearing witness to who she will become.

All photographs courtesy of the author