Belgrade

March 1998 – June 1999

17 March 1998 I tremble, my feet tremble while I am asleep. Why do my legs tremble as if an electric current is passing through them? Is it because I will need them to run away and fear they will fail me? I fear everything. I fear death and killing. I fear not being able to imagine the future. I watch my children with a sense of guilt. Here in Serbia in the eighties and nineties I should have been sensible enough to realize I should never have children.

When I was pregnant, in the eighties, we didn’t have electricity for days. It was winter, and Tito had just died. Tito always told us we had lots of electricity. He said we were a rich country, the best in the world, and I believed him. I liked his face. I’d known it all my life, I thought he was my grandfather. Once, when I was a little girl and lived with my family in Cairo, I was supposed to give him flowers, but then they made me give flowers to President Nasser of Egypt instead, because I was taller and Tito was smaller, and Nasser was taller and the other girl was smaller. Since then I’ve always associated being small with privilege and beauty.

I grew up abroad, first in Egypt and then in Italy. My father was an engineer who became a businessman and my mother a paediatrician who gave up her career to follow him. I grew up switching between languages and cultures, speaking Serbian at home while the world around me spoke Arabic and then Italian. It was years before I managed to turn this painful Babylon in my head into an advantage, and now I am writing this diary in English, which for me is not the language of intimacy or love but an attempt at distance and sanity, a means of recalling normality.

20 March It has been a terrible month. The killing has started again, this time in Kosovo. Once again we are witnesses who cannot see. We know it is going on, but we are blind. It’s not even the killing that makes me die every day little by little, it’s the indifference to killing that makes me feel as if nothing matters in my life. I belong to a country, to a language, to a culture which doesn’t give a damn for anybody else and for whom nobody gives a damn. And I am completely paralysed. I am not used to fighting, I am not used to killing. I don’t believe anybody any more, not even myself. I have stayed here and I have made a mistake: victim or not I have become one of those who did nothing for themselves or for those they love. I have a feeling that I will not survive.

22 March I spent yesterday evening with three young women who seemed so bright and happy – perhaps because their hopes are still intact. Even war and injustice can’t completely destroy the hopes of those who haven’t lived yet, like my daughter, who is only thirteen. They looked up to me, these girls, they would like to be me in twenty years. They don’t see my anxiety, my shattered inner self. They thought I was wise and beautiful and sincere. And so I was – I was fine last night. We laughed about sanctions, about the war, about our destiny as people who will have to flee – because we know we will have to leave for a new life or we’ll become like the others. My husband said every country has its terrible political and social upheavals, and some people run away from what they are born into. I know that’s true, but here there is nowhere to run to except to places just as oppressive as those you are running away from. I know that despair from my first exile and I fear that choice.

In 1992 I was in Vienna, waiting for Belgrade to be bombed. I was a Serb in Austria, a country whose language I couldn’t understand. Then in Italy it was even worse: I understood only too well that I was a bad Serb responsible for the atrocities of war and guilty for not stopping them.

25 March Today they are talking about sanctions again. I don’t bother to think what will become of us, I just know I have to survive. They say the mind never dies, well I think the mind dies first, if you are harassed. To preserve the mind one must defend everything that the mind is made up of. I am fighting to save my mind for a better time.

26 March This is another politically correct war rather than a moral one. I have seen it in Bosnia, in Croatia, and now in Serbia: Americans are being Americans and politically correct, which is painful for everybody else who is not American and politically correct in a different way. Americans don’t get it. We have a different idea of everyday life, we have different emotions, we have different ideas about help. And we perceive intrusive American help as helping the self-image of the American nation. In many ways we, both victims and aggressors, know that the Americans are right. We would all like to be Americans, but it’s impossible. The Americans don’t want us to be Americans, they want us to be the Other, they want us to be a territory where new plans can be implemented. I don’t like feeling like this. Inside Serbia I have taken the high moral position of a traitor. I defend foreigners, Americans, and foreign intervention against national barbarians. But I don’t like to be thought of as the Other by anybody, particularly not the biggest power in the world.

The other night, my neighbours wrecked my car. They did it openly, saying they’d lost their cars, so why should I have mine. I know I should fight back, but how? The law doesn’t exist any more, and the police won’t protect a woman with a luxury car. They believe only men should have luxury cars in Belgrade today.

One of my neighbours is a poor alcoholic who didn’t adapt to the new ways of making money through crime, so he lost his money and his mind and now he drinks beer all day on the pavement. He’s neither a good man nor a bad man, just one of thousands of street people who subsist in the moral and physical decay that is modern Serbia. He’s not alienated from society. He is in touch emotionally and rationally. He understands the New Order and is following it. We are both part of the New Poor. Before last night, the only thing that divided us was my car parked on the pavement where he drinks his beer. So he tried to do away with the symbol that stood between us. I understand it. There’s no point in explaining that cars shouldn’t be scratched, or knifed, or spat upon. He has suffered, so why shouldn’t my car? And the criminal on the other side of the street with the big red sports car watching us – it goes without saying: we know, he knows, everybody knows – his car is not going to be touched because he carries a gun.

27 March My parents are ashamed of me, ashamed of my choices. They suffer with every word I utter and rejoice at every word I don’t. They want me silent and obedient. They say, ‘We gave you everything. Don’t question it. Just keep this wonderful world we made going.’ And the truth is, my generation won’t have time to change it. They are such brave parents, ready to sacrifice my life for their country. But I am a coward child; not ready to die for any country, or fight a war for any just cause. They and people like them fought all those Balkan wars, produced all these leaders who are ready to appeal to people to fight in more wars; for land, for graves, out of pride, out of prejudice. What I resent is that they never told me the truth about their lives. They never told me about their wars, or about how they survived hunger and killings to make their country perfect. Did they kill? Did they see people being killed? Was it all worthwhile?

7 April Do we want to be ruled by foreigners or not? That’s the question put to us in the upcoming referendum. Can it really be so simple? Here we have a ruthless dictator convincing us that we are the ‘wild Serbs’ we are not. He falsifies our thoughts, our roles, our desires, our history. We are drafted into a war we don’t understand and don’t want by cowards who are afraid to negotiate because they can’t be rational.

I think of myself as a political idiot. Idiot, in ancient Greece, denoted a common person without access to knowledge and information – all women, by definition, and most men. I am unable to make judgements. I see no options I can identify with. Is that normal? Is it because I am a woman? All the political options of my fellow men sound aggressive, stupid or far-fetched compared to my simple needs. I need to move, I need to communicate, I need to have children, I need to talk, to play, to have fun. They speak of history, of historical rights and precedents, but it’s not my history they speak of, or if it is, I had no part in it. They talk of blood, of pride, of rights, but I am losing my mind because of lack of love and understanding. All our instincts are focused on dying or surviving.

14 April Yesterday I jumped on to a bus, a terrible, stinking, falling-to-pieces bus. It was a dangerous trip for several reasons: the doors wouldn’t close and people were hanging out of them, pickpockets were everywhere, and lots of old sick people who can’t afford medicine were coughing and spitting on everybody. But once on board I realized I was surrounded by the happy, pretty faces of young schoolgirls. It was a group of ballet dancers coming back from performing a successful show. I thought of their parents somewhere, grey and tired and anxious like me, young-old people gone half mad with fear and worry. But watching the beaming faces of these young girls, their arms and legs long and thin like some African tribe, I thought, my God, you can’t stop beauty, you can’t stop joy, you can’t stop creativity. And I looked through the window at downtown Belgrade, full of young boys and girls on a Saturday night, with the same shoes, the same jackets as kids in New York or Paris, and I thought, I know some of them are criminals, and some of their parents starve in order to make them look like that, but even so, you can’t stop joy and beauty. It grows faster than crime and death.

15 April Today I saw a Serbian family on the road in front of the UNHCR office near my flat in the centre of the city. They were terrified, they had bags and suitcases around them blocking the pavement. A middle-aged woman was crying, a young girl was ashamed to look at us, and the men were just sitting and staring in front of them. Men often do that when they become powerless. It made me shiver. They were in my city, in my street, Serbian refugees from Kosovo. And we were part of a common destiny.

Some twenty years ago my aunt had to emigrate from Kosovo with all her family because, as Serbs, they were harassed by the Albanians. They left all their goods, they sold their house at a loss and started life anew here on the outskirts of Belgrade. That is a common experience in my father’s family. They came from Herzegovina and are now scattered all over the world.

The family on the road reminded me of other refugee families I have seen in the past few years, though only a few came to Belgrade. This time the Kosovo Serbs will all come here. My city will change once more. But it isn’t really mine now. I don’t feel safe here, or happy, or free. I’m a refugee in my own city.

18 April The pensioners are being told they have to vote ‘yes’ in the referendum in order to get their pensions, in order to be able to buy bread and anything else. The result of our referendum is already pretty certain. Nobody dares to alter the ideas of Big Brother and his political murals on which our personal lives are spattered like cheap paint.

20 April This morning I couldn’t buy milk. Just as six years ago when the war started, it started with milk, a symbol of maternal need. The message is: death to the children.

24 April The referendum was yesterday. One of my friends said, now they’ll come and shoot us because we didn’t vote. I told her she was just being paranoid. After the vote the President gave a speech. Everything about him, his face, his voice, his words and emotions, was so familiar – that pathetic, patronizing tone that knows what’s best for me, just like my father. This president, whom I know to be a corrupt liar and merciless enemy, worries for my future – that is why he is sending me to war, that is why he is fighting the rest of the world. That is why he makes me weep.

30 April We spent yesterday evening with an American friend. She was asking us how we could still talk to friends who had become nationalists. I was so nervous I could hardly sit down. Then we heard the news: we’ve got sanctions. Our friend was afraid her plane wouldn’t leave. She asked me what the sanctions were about, what our lives would be like. I said, I don’t know. I can’t control my life any more. I feel utterly depressed, absolutely lonely.

Most Americans we meet are just silent. I remember at the beginning of the Serbo-Croatian war we went to the International PEN Congress party in Vienna. Nobody wanted to sit at a table with me and my husband – with Serbs – but an Austrian writer came with his wife to our table and talked to us without mentioning the war. I thought we were safe in our invisible pain. But at the end of the evening, he simply said: ‘If you need money, if you need a flat, any time, we are here.’ I started crying and he said: ‘I remember when I was eleven, I was a Nazi for five minutes.’ His name was Peter Ebner and his father was killed as a German soldier at the Russian front.

6 May Today I went to a meeting of the Women in Black. We were about fifty women – feminists, refugees, activists, women running non-governmental organizations, women driven mad by the past wars – plus a few gay men. Most of the women from NGOs and feminist groups saw a parallel in Kosovo to the wars in Croatia and Bosnia. I saw it differently: we have had an apartheid state for Albanians in Serbia for the past ten years at least. In Croatia and Bosnia, it wasn’t like that. That was about boys’ games and loot.

I was so upset I could hardly speak. I started swearing and my voice trembled. ‘The police are entering houses to mobilize men all over Serbia . . .’ Some of the women suggested peace caravans, peace protests, pacifist walks and a global protest against mobilization. But we did all that six years ago and nobody listened to us, so why would they listen now?

9 May Today the international community decided on another package of sanctions against Yugoslavia: one more step on the path to total isolation. I was in the market place where people were talking about prices and inflation, but the hole in the middle of their sentences represented their knowledge of what had happened. Today the President’s wife opened a maternity hospital in Novi Sad. For two hours everything came to a standstill. Women already in labour were sent away. But no political power in the world can prevent children being born. Only afterwards can power transform a precious little life into a miserable existence without a future. Yes, power can do that.

16 May What are they doing to us? We are entering the long tunnel of fascism: fascism with a domestic face, that of your neighbour who beats his wife when she disobeys, and pisses on the staircase when drunk. The face of a big funny man who is dangerous because he doesn’t know his or your boundaries.

26 May Today the nationalists passed a new law against the autonomy of the university. They say students should just study and not care about politics. Those who protested were beaten and some of them arrested. Everybody else was confused and silent. Most people here have been completely broken down by the political shit of the past five – the past fifty years. Maybe there will be strikes, protests, but more likely nothing will happen at all, and we’ll be back in the dark ages. Does anybody enjoy this parade of totalitarianism? Are these few in power good for anyone? I don’t believe so. Serbs are like women who don’t want to be feminists, who are satisfied with the old stereotypes, no equality just invisibility. I can see how that happens. I used to feel that way too: it’s a natural state, you’re born into it. Once you come out of it, you may lose everything, but there is no going back.

29 May I met some people from the university: there will be no mass protest against the totalitarian laws. My friend who teaches at the university and whose father is a retired professor said he told her triumphantly: ‘Now you’ll have to obey. Now you’ll have no more freedom.’ This is a war between us and our parents, between political idiots (like me) and political criminals (like them): no winners, no losers, no right ways, no middle ways, only permanent struggle and bad dreams.

3 June A few days ago a young soldier was killed during his regular training on the Kosovan border with Albania. Yesterday his last letter to his parents was published in the paper. He couldn’t have written anything more direct, cruel and true: ‘Just stop it, all of you who think you are doing something right, just stop it.’ I could imagine what his parents felt. I could have been his mother.

Some years ago, I found myself in the lift in my building with the mother of my next-door neighbour, a soldier who had been killed at nineteen. He was a punk, he wore an earring and played loud music. But when I saw her I started crying, I didn’t know what to say. She embraced me and kissed me on both cheeks. She said: ‘Now, now, stop it, he was a brave boy and he died for his country.’ I wanted to shout at her: ‘You’re crazy, you know it’s not true, he was killed by people who were taking everything from us, our lives, values, goods, children.’ But then I saw her face: I knew she knew it. But she knew better, too. She was pleading with me silently: don’t say it, don’t take his death away from me. Death took him, leave me his death to be my company through life. (Mothers, I thought, traitors to the nation, traitors to their men, bearers of life and death. Mothers are like court jesters: they tell the truth but it has no impact.) She closed the lift door after me. His music will never disturb me again. Very soon I moved out: the silence was too much like my inner solitude. I couldn’t bear it.

4 June The cheapest photocopying shop in town is in my street. To reach it, you have to climb a narrow staircase over the cellars where the gypsies live. They are a local institution. In the last few years the son has fathered two babies and now they are seven in one room. They all drink and make scenes, swearing, cursing or making fun of passers-by. Today I went to the store to photocopy my stories for some Swiss friends. Coming out I found the old gypsy woman lying in a pool of blood. She was screaming at her husband, ‘Radovan, you are killing me.’ He was running round her, and their dog was licking her blood. The babies were a few feet away, but not crying. I stepped over the blood and decided to leave them to it. Other people were doing the same. She lay there screaming for another half-hour until her husband pulled her to her feet and cleaned her up. They were both so drunk they could hardly stand. Then they sat on their usual doorstep and opened another bottle of beer. The babies didn’t cry, the dog didn’t bark. We’re used to their love quarrels. Usually she beats him and he rarely strikes back, he’s smaller and less aggressive. She has a big handsome lover who comes over sometimes when the husband is away, then when he comes back they all scream and fight, usually all night. We can’t sleep because of the noise, but their quarrels are so interesting we just stand at the window and listen.

8 June All over Belgrade men are huddled together in bars whispering about the future over their beer. They say blood will be flowing on the streets of Belgrade in two weeks. They say we will all die of hunger, disease and street violence. They say our country is finished, our children are doomed, we have no future. I have listened very carefully to these men who both move me and depress me. But I have realized I don’t believe their stories. They’re like little boys, these men, afraid to be killed but ashamed to cry. They’d rather damn the world than say no to the war. They regard me as a political idiot. And that’s what I am. I’ve chosen the word myself in order to be safe from their language. I still believe more in words than in democracies.

12 June We are expecting NATO troops to bomb selected targets in Kosovo and in Yugoslavia. It might end the war there – I wish it would – or just result in all-out war. Everybody is speculating, but I’m over the war shivers now. I had them so strongly six years ago when I left for Vienna that the thought of them now seems no more than an echo. Pain, like fear, has a natural limit. After that comes indifference.

17 June Parents from all over the country are protesting against their children being sent to fight in Kosovo. I wish I could see their faces. They must be special people, honest enough to admit that it is still their old war that has been going on for the past sixty years at least.

The woman who is helping me with my housework is a refugee from Knin, Croatia, from the Storm operation in 1995, when they were bombed at five in the morning and fled in nightgowns, on foot or on tractors. She is trembling today, she can’t sleep and is afraid it will happen again here. She wanted me to calm her down but I feel exactly like she does. I tremble, too; I don’t sleep, either. We both feel guilty for being in the wrong place once again, for having children we can’t protect. And our men blame us for the same things. I tried to explain to her that it is not our fault, that our feelings of responsibility and guilt are irrational. But they are as real as they are ridiculous and groundless. Our fear and anxiety is so great that we clean, dust, cook all day long, only pausing to listen to the news. We behave in exactly the same way, me and my cleaning woman. We go on cleaning and feel guilty.

23 June Tension in the air like electricity before a storm. The gypsy woman in the basement is rolling half naked on the pavement covered in spit, rolling on the glass from her broken beer bottle. Not even the conceptual artist Marina Abramovic in her latest performances could be that good. She’s drenched in blood. ‘Police! Help me!’ she shouts. ‘They tried to kill me.’ Then she gives us a long speech about life, love, war and simplicity. She does this more and more frequently. Every day, I feel as though the social and emotional space between her and me is becoming smaller. When she sees me she says, ‘Hello sweetie’.

I dropped by the Women’s Centre. A friend asks me if I’ve heard what the policemen are doing in Kosovo. We continuously receive e-mails: they rape, they kill, the same as in 1992 in Bosnia. On television we hear only about the Serbian people’s centuries of suffering. An American woman asks me if I want to go to Kosovo and see for myself. But I don’t have to. I can imagine how it is.

5 July Last night, in front of a police station in the centre of Belgrade, I saw a dozen policemen with sleeping bags and machine-guns ready to leave for Kosovo. Their families were with them: mothers, fathers, wives, babies. The policemen were young and completely calm, the families were worried. It was unnerving to have to pick your way through the guns and sleeping bags on the pavement. I didn’t dare ask them anything, not even to look after their machine-guns so we could cross the street safely. They behaved as if their guns were in the right place. In my country uniforms always take away the power of speech from citizens because uniforms carry guns, and citizens carry fear, so there is a permanent civil war going on between uniforms and civilians.

The Serbian war criminal who destroyed a city in the war with Croatia and killed many people committed suicide in the Hague. His body was brought back to Serbia for burial. People are talking about him as if he was a hero.

7 July Today is a state holiday, something to do with the Second World War. The shops are closed, old people haven’t had their pensions delivered for a month and even then they only received half the miserable sum. The black market is full of people who have dragged themselves through the humid heat to get a carrot, an onion, a tomato for free. The gypsy woman under my window is singing her lungs out in a lullaby for a baby who cannot sleep because of her song. It’s like a scene from a cabaret. I feel sick, I can’t breathe because of all the dirt and sadness. Everything is falling apart: no pensions, no cash on the streets, and in the shops, no sugar, no oil. Foreigners taking over the decisions, without much knowledge or goodwill, but with energy and anger – Wild Serbs make the world go wild. I wonder if we will have public soup kitchens in a few months’ time and coupons for buying clothing, like my parents did after the Second World War. Normality is a myth by now.

12 July Last night I was in a restaurant with a friend. It was dusk and we were sitting on the terrace overlooking the Danube when a swarm of mosquitoes attacked. There was pandemonium: women screaming and rushing inside; men moving chairs and tables out of their way, and I thought if a single bomb landed here by mistake, their nationalism would vanish. Their proud Serbian nationalist small talk would fizzle out like air out of a balloon. My friend and I stayed outside: the mosquitoes drowned in our sauce, and we ate it and them as they ate us. The nationalists left all their food behind on the terrace as if it was free. It reminded me of those stories about the Russian aristocracy during the October Revolution, but a cheaper version.

31 August Today a wonderful light fell on Belgrade from the sky. I nearly said to my husband: ‘I love you, let’s have another child and stay here for ever.’ Otherwise, I’m packing in my head, switching through countries like satellite channels: who would accept me? Hardly anybody, but still, the more countries I exclude the closer I get to the one waiting for me.

30 September My cousin has been hospitalized for AIDS. She is dying. She got better and then at a certain point she got worse. I went to see her the night after we had an earthquake when everybody was out on the streets thinking it was NATO bombs. But she escaped the earthquake, and she would escape the bombs. She looked like a saint, a beautiful medieval picture, small, white and immobile. She smiled at me and I didn’t dare to cry, I just wanted to faint. Who cares about bombs or earthquakes when you have a chance to stay alive? She has none. With her will go my childhood, my ideals, my dreams. Who cares about NATO if she is gone? I don’t want to be left alone with the ideas of happiness, beauty and bliss we shared as children.

During the night I hold my child tightly, trying to repair the bliss of childhood, but it is no use. There is no bliss in it. I see my dying cousin every day. I feed her like when we were kids. I say, stay alive. She says, I have no place to go. I say, stay alive for me, I will find you a place. Her eyes sparkle, she takes hold of my hand feebly. She still has beautiful hands. I say, promise.

In the hospital ward the water tubs are full of vomit. Most of the expensive medicines are unavailable and food is brought in from outside. The patients share their food. People don’t stay long in the AIDS department: relatives just rush in and out, out of duty, out of fear. The nurses don’t talk to patients or visitors. They think everybody knows all that they need to know: those who cross this threshold, abandon all hope. But then all hospitals here have had this kind of atmosphere for the past five or six years. Death reigns. My father spent hours waiting for the hospital to open in order to be among the first to get a pacemaker. It wasn’t a question of money, but of sanctions: no pacemakers for Serbs. And he got it. When he had a heart attack there was no money for batteries for the machine to regulate his heart. Then the young man in the next bed died. I happened to be there. My father said: ‘The poor man, he died; grab his covers, I have none.’ And I did, I grabbed the covers from this dead stranger while his body was still warm. And as I did it, I felt a connection to him. Through his warm covers he had suddenly become familiar to me. I thought, this is not death, this is murder. And I got angry. Let’s find the murderer.

10 October Yesterday, in the queue to pay new taxes – for the war to come, for the monasteries, for weapons against Kosovan Albanians, for refugees, NATO, the whole world – I saw that people were worse off than I ever realized. They were rude and dirty and untidy, and when I looked at my image in the mirror, my hair was dirty too: I am leaving my hair unwashed as a protest against the war.

These people despise people like me who are afraid, even if I’m their own flesh and blood. They clean their cellars and buy their candles and say they will defend their country until the very end. Is it possible nobody is afraid? Is it possible that pride can win out over fear, and if so, where is my pride? I am not proud of my proud people, they killed and humiliated others. Even if they did it under orders, they still did it. And yet I am not ashamed of my people because I don’t consider them any worse than most others, as such, I just see them as people who have no chance to be better.

Yesterday night I went with the Women in Black to demonstrate in the Square of the Republic. The police were protecting us from the crowd who were spitting on us and shouting, ‘Whores, whores . . .’ We’d all taken small rucksacks with ID, money, spare clothes etc. in case we got arrested and tied to the trees as NATO targets, which is what Seselj, the deputy prime minister of Serbia, promised us traitors. My parents call me a traitor for not supporting them; my husband does the same for not supporting him; my daughter, too.

11 October Can anything be as bad as this feeling that imminent death is a lottery? Last night we had a birthday party. We couldn’t get drunk, but we couldn’t stop laughing. It was the kind of behaviour I’ve observed at funerals.

18 October Last night, the night of the new NATO ultimatum, I wanted to die. Just like my gypsy friend I got drunk, drugged and aggressive. I wanted to kill. I wanted to die. I bashed my head and concussed myself, made my nose bleed and ended up with a broken finger. I wanted to excise the conflict inside me – the conflict all around me. There. My war.

13 November My cousin died on 10 November. I had a vision two days before that it would happen, the day, the hour. I went to the hospital. They wouldn’t let me in, so I stood in front of her window as she died. It was a beautiful day, sunny and clear. I entered the ward, gave the flowers I had brought to a very thin guy who seemed nice and very sick. The young lady doctor didn’t mention the word AIDS when I asked the immediate cause of death. She said: ‘You know what this ward is for.’ This is exactly how all people involved with AIDS, whether patients or doctors or relatives, deal with it, through evasion. When I left the hospital I went for a long walk. I felt privileged to have been there, for having such a lovely cousin who made even a ghostly sickness like AIDS lovely. She was calm, smiling and at peace. She even confessed her sins to the Head of the Serbian Church when he came to visit the ward, though she wasn’t religious and I doubt she thought she had any sins, even if her life, seen from the outside, was a sin. Because my lovely cousin was a junkie, an outcast, and a writer who never published. Telling her story straight would have meant losing her friends, her social security, her job. She preferred faking normality because she was brave, much braver than me.

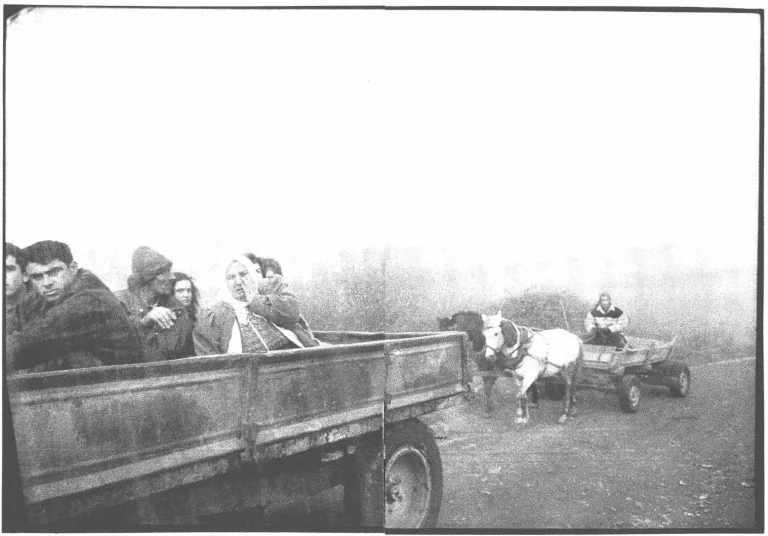

Kosovan refugees leaving the village of Vucitrin after their houses were burned, November 1998.

Photograph © Alex Majoli / Magnum Photos

1999

On 24 March 1999, NATO began air strikes on Yugoslavia.

26 March, 5 p.m. I hope we all survive this war: the Serbs, the Albanians, the bad guys and the good guys, those who took up the arms, those who deserted, the Kosovo refugees traveling through the woods and the Belgrade refugees traveling the streets with their children in their arms looking for non-existent shelters when the sirens go off. I hope NATO pilots don’t leave behind the wives and children I saw crying on CNN as their husbands took off for military targets in Serbia. I hope we all survive, but that the world as it is does not: the world in which a US congressman estimates 20,000 civilian deaths as a low price for peace in Kosovo, or in which President Clinton says he wants a Europe safe for American schoolgirls. When the Serbian president Milutinovic says we will fight to the very last drop of blood, I always feel they are talking about my blood, not theirs.

The green and black markets in my neighbourhood have adapted to the new conditions: no bread from the state but a lot of grain on the market; no information from state TV, but a lot of talk among the frightened population about who is winning. Teenagers are betting on corners – Whose planes have been shot down, ours or theirs? Who lies best? Who wins the best victories? – as if it were a football match.

The city is silent but still working. Rubbish is taken away, we have water, we have electricity, but where are the people? Everybody is huddled together inside waiting for the bombs: people who hardly know each other, people who pretended not to or truly didn’t know what was going on in Kosovo, people who didn’t believe NATO was serious all along. We all sit together and share what we have. A feminist friend asked me to organize a consciousness-raising workshop. Another wants me to go with her to Pancevo, the bombed district on the other side of Belgrade, to give a reading of my novel. But there is no petrol. We’ll have to buy bicycles.

We phone each other all the time, passing information back and forth: I realize the children are best at it, they prefer to be doing something in an emergency. We grown-ups nag at them with our fears but they’re too young for speculation, they deal with facts and news. Most of them are well informed through the children’s networks, foreign satellite stations and local TV.

I think of our Albanian friends in Kosovo. They must be much worse off than we are, and fear springs up at the thought.

I’m sleeping heavily, without dreams, afraid to wake up, but happy there is no real tragedy yet; we’re all still alive, looking at each other every second for proof. And yes, the weather is beautiful, we enjoy it and fear it: the better the weather, the heavier the bombing, but the better the weather, probably the more precise the bombing. I only wish I knew if we needed bad weather or good weather to stay alive.

The sirens are interrupting me, a terrible wailing up and down. I switch on CNN to see why they’re going off in Belgrade but they don’t know. Local TV will tell us when it’s all over.

NATO stepped up air strikes over Yugoslavia.

28 March Belgrade is rocking, shaking, trembling. We are entering the second phase of NATO intervention. The sirens went off today for nearly twenty-four hours.

Sign in to Granta.com.