I was looking for something else, a ceremonial sash to decorate my father’s coffin at his funeral. On top of a tall chest of drawers in his bedroom was a flat, dark blue box, which I took down and placed on his bed. What I found inside was not ceremonial: it was a canvas bag with purple piping around its edges. Embroidered onto it were various female figures looking like Girl Guides going about chores, and a cooking pot above a flame. Next to one of the figures are the words one of us and changi jail, spring 1942. Stamped on a piece of cotton sewn inside is cell 001.

The canvas bag belonged to my father’s aunt by marriage, Daisy Thomas. It was given to her by her Japanese captors after the Fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942 to pack the few possessions she was allowed to take with her to prison. Her husband, Shenton Thomas, was governor of what was then called the Straits Settlements, which included Singapore, the port once so central to the British Empire’s Asian interests. Daisy and Shenton were separated immediately after the surrender, and Shenton was marched through the streets of the city to Changi Prison by the Japanese in an attempt to humiliate him. The two saw each other again briefly in May. Then Shenton was sent to a prison camp in Taiwan: two years later he was transferred to the Japanese camp at Hsian, Manchuria, where he was for the rest of the war. Daisy remained in Singapore at Changi, a prison designed for 600 inmates. The Japanese packed 3,000 prisoners of war into the building, soldiers and civilians, men and women; 800 of them died while incarcerated.

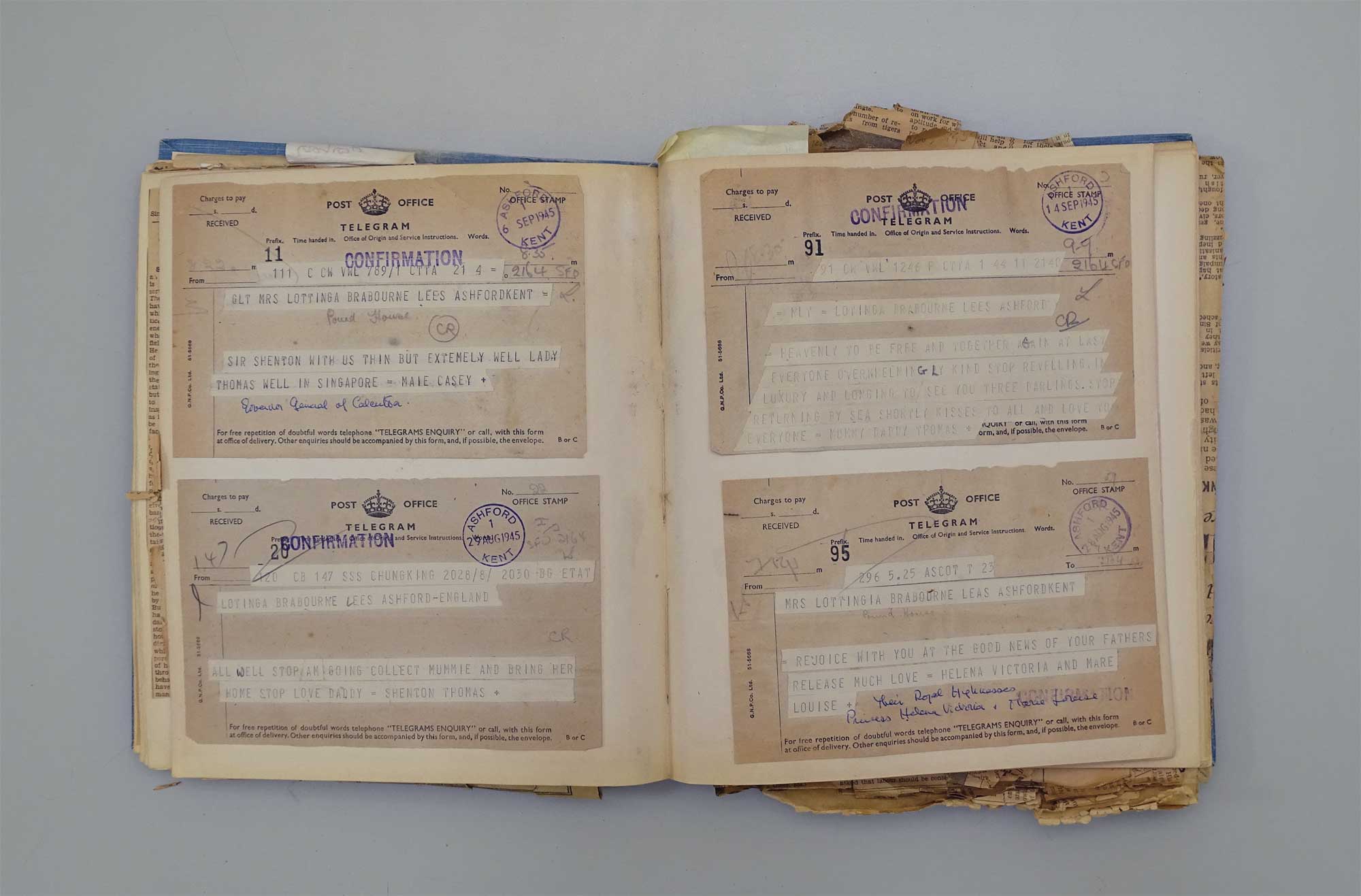

Two days after the Fall of Singapore, Daisy and Shenton’s daughter Bridget received a letter from the Colonial Office. She kept it in a scrapbook, which she must have given to my father. ‘I am afraid that you have been going through a very anxious time during the last few weeks and I do hope you have found some reassurance from the report which has appeared in the Press of the safety of Sir Shenton and Lady Thomas,’ the letter began. Neither Shenton nor Daisy ever spoke about their prison years, but you wonder whether ‘safe’ would have been the word they would have reached for to describe their internment. Cambridge University Library has amassed an enormous archive about the people held at Changi Prison during the war; it includes the newspaper that the prisoners made for themselves. Conditions were hard, but the adversity brought out an esprit de corps.

‘We did everything for ourselves,’ said W.F.N. Churchill, a colonial official who wrote extensively about Changi after the war. ‘With the poor materials and resources at our command, we made a good show of it. We produced cooks, electricians, water engineers, plumbers, tailors, roof repairers, carpenters, laundry workers, health workers, doctors, chemists and opticians. Fortunately we had a cross section of the whole community. The Japanese would never have admitted it, but I think we did, in considerable measure, earn their respect.’

As I realised after my father’s death, he was meticulous about archives and papers. Inside the bag, he had placed an explanatory note as well as a book, Shenton of Singapore, written by Brian Montgomery in the early 1980s. The author was Daisy’s cousin, and the brother of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. The fear at the War Office in London was that if the Japanese had known they had a Montgomery cousin in their hands, they would have tortured her. The fears were misplaced because the Japanese treated all prisoners atrociously; 30,000 POWs died in Japanese prisons, of starvation, disease and torture.

Brian Montgomery quotes from a telegram the king sent to the governor on 6 December 1941, soon after the Japanese commenced their attacks around the Pacific:

the storm of japan’s wanton attack has broken in the east and malaya bears the first assaults of the enemy stop at this fateful moment assure you my high confidence in your leadership stop i am at one with you and their highnesses the rulers and peoples of malaya in the trials which you are sustaining stop

The king was referring to the leaders of Malaya’s principalities over whom the empire ruled. The telegram continued:

i know the empire’s reliance on your fearless determination to crush this onslaught will be fully justified and with god’s help the devoted service of every man and woman in malaya shall contribute to our victory ends

Two months later Singapore fell.

Below the entry detailing the Fall of Singapore is the one for the same date the following year. ‘High wind, but not cold. We all had our fingerprints taken. Cold rather better. Bit of meat and gristle in evening soup.’ A year later: ‘Showery a.m. then overcast and cooler.’ Meteorology came naturally to Shenton – my father, who saw a lot of him in the 1950s, would say that weather was always a topic of conversation.

Sign in to Granta.com.