Forty or so years ago, Bradford’s Italian community coined a new verb – bookare. Every springtime, as attic-stored suitcases were dusted down, as plastic jerrycans waited to be funnel fed with olive oil and wine, you would hear the same excited incantation: Allora, vi siete bookati? The verb prenotare, to book, did not suddenly fall out of favour. As far as MOTs and doctors appointments were concerned, it retained its regular usage, but when it came to finding flights to Naples, Rome, Palermo and Brindisi, you were always told to bookare early.

My family had yet to join in with the whooping applause that accompanied every descent onto Italian asphalt. The journey to my father’s hometown of Erchie, on the knuckle of the Salentine heel, was by two-tone Vauxhall Cresta: three boys on the backseat, boot overloaded with pots and pans, paraffin lamps, rolls of cotton and worsted, tinned foods and colouring books. With its Batmobile tail fins and a chrome-plated grille – obligatory pepper-red cornetto dangling from the driver’s mirror – the primrose and honey Cresta cut an unlikely sight among the three-wheeled Piaggios and motorini that trundled in and out of the orchards and olive groves. ‘Ayy, Americani,’ barefoot children sang out, as my father proudly navigated his village streets, steering us into a swelling horseshoe of awaiting family and neighbours.

Looking back, I can’t help but think that the world he had driven us into was the same timeless enclave of Bassa Italia that physician and writer Carlo Levi had been exiled to in the 1930s, when his opposition to fascism and the war in Abyssinia saw him banished to the village of ‘Gagliano’, eighty miles to the west of us in Basilicata. My grandparents’ tiny home was a marble-floored and whitewashed ode to agrarian life centuries past. There was no television or running water. In the small bougainvillea-fringed quadrant to the back of their house, I watched black ants commuting between between large terracotta urns and a wooden rack, on which slender, yellow-spotted tobacco leaves had been bunched and threaded. This was the lot of the peasant sharecropper, ‘the bare and dramatic austerity’ that Levi had written of in Christ Stopped at Eboli.

We followed my father and assorted relatives up an iron ladder and onto the flat roof terrace that had been his childhood hideaway and watchtower. He pointed to the scuola elementare, to the aqueducts that had brought fresh water to the dry plains of the Salento in the early 30s. Somewhere out of eyeshot, there was a house where Mussolini had stayed during a five-day-tour of the southern plains, when he came to stand on tractors, to shake his fists at the contadini and proclaim them his foot soldiers in the ‘Battle for Grain’.

As I listened, something hit me: the language that my grandparents, uncles and cousins spoke was not Italian as I knew it. They did did not say andiamo for let’s go, but sciamani. The local primitivo wine was not vino, it was miero. My nonna, rheumy-eyed, smiling, rosary in hand, spoke a Latinate dialect that didn’t bother to name the days of the week. Tomorrow was crai, the day after tomorrow puscrai, the day after that was puscridri.

Beyond this recondite argot, there was a welter of new sights and sounds that needed to be named, to be learned. The hot and stupefying wind that blew in from the Maghreb was the sirocco; the cool northerly was the tramontana; the metallic trill that we heard in campagna was the sound of grilli; the flying army of insects that buzzed around our netted beds were zanzare; the fortified farmhouses that we passed on the way to the coast were masserie. Within weeks, the three of us were were talking – and gesturing – like locals, paesani.

It didn’t last. Back home, we soon fell into the habit of speaking English. Ignoring all parental bribes and humiliations, and remaining impervious to serial pleas from friends and neighbours, I joined my two brothers in a resolute linguistic embargo. There was little use trying to win us over. My cousins next door spoke in English, as did my best friend Angelo at no. 76. Besides, now that my eldest brother was sixteen, there was no realistic chance of us ever settling permanently in my father’s hometown. It was a pipe dream, a fantasy. You speak Italian, we speak English. That was the deal.

The nostalgia that overcame my parents during the first throes of our verbal estrangement came to cast a deep and lasting spell on me. I liked to hear the story of Bella Venezia and the seven bandits, and Micheluccio the laziest boy in the world. I wanted to learn more about the derring-do of Columbus and Garibaldi, and the good work that Il Duce had done for the poor peasant South. And, even at this age, I guessed why my father’s voice wavered and cracked as he recalled the cypress trees in Giosuè Carducci’s ‘Davanti a San Guido’, the one poem he could summon up from his schooldays: Spite of the stones you used to throw at us we love you / Just the same as ever; oh, they never hurt us much. For my mother and father, the past and present had both become foreign countries.

A powerful ally soon came to their assistance, helping to ensure that their youngest turncoat would never be fully anglicised. When I was seven or eight, the Italian Foreign Ministry directed its UK consulates to roll out a programme of lessons in ‘La Lingua e Cultura Italiana’ across all UK towns and cities with a sizeable emigrant population. Since many second-generation Italians were already of school-leaving age, the programme, which shadowed the curriculum in Italian state schools, was a little late in coming. Still, I was just the right age to be inculcated into its textbook lore and language.

Foregoing Saturday mornings at the Unit Four Picture House, I took my place in a class of young Italians and began to make my way through the pages of Oltre Le Frontiere and Noi e L’italiano, learning about the history and geography of our boot-shaped motherland, and getting to grips with the grammatical peculiarities of the modo indicativo and modo condizionale. What I did not yet know was that more than twenty years earlier, in the spring of 1952, my father had also found himself in a makeshift Yorkshire classroom, booklet in hand, trying to master the working essentials of an altogether more foreign language.

*

My parents met at a dancehall in Bradford, in May 1956. She was a twenty-year-old Sicilian girl who had never seen snow. He was twenty-eight and had left ten hectares of good soil on the Ministry of Labour’s reneged promise of work in the mines of South Yorkshire. They talked. Their hometowns were both under the protection of Santa Lucia, the patron saint of the blind. They both worked in factories, in a hubbub of foreign voices. And before the brassy notes of Cherry Pink and Apple Blossom White carried them to the dancefloor, they found that one of them was a fugitive from a psycholinguistic experiment that went by the name of BASIC English.

Business, Academic, Scientific, International and Commercial English was the brainchild of linguist and psychologist Charles Kay Ogden (1889-1957), who conceived it as an ‘all-purpose, international auxiliary language’. Composed of 600 Things, 100 Qualities, 50 Opposites and 18 ‘Operations’ (come, get, give, be, have, etc) that did the heavy lifting usually allotted to 4000 common verbs; BASIC English’s strangulated syntax and clunky portmanteaus had, by 1939, reached over 25 countries. Calling time on the cacophony of world languages and dialects, its neo-imperial, softly-softly mission was ‘debabelization’ – a word that was nowhere to be found in the Lilliputian dictionary of BASIC words, or in The Workbook of BASIC English that my father was given on arriving at Maltby colliery.

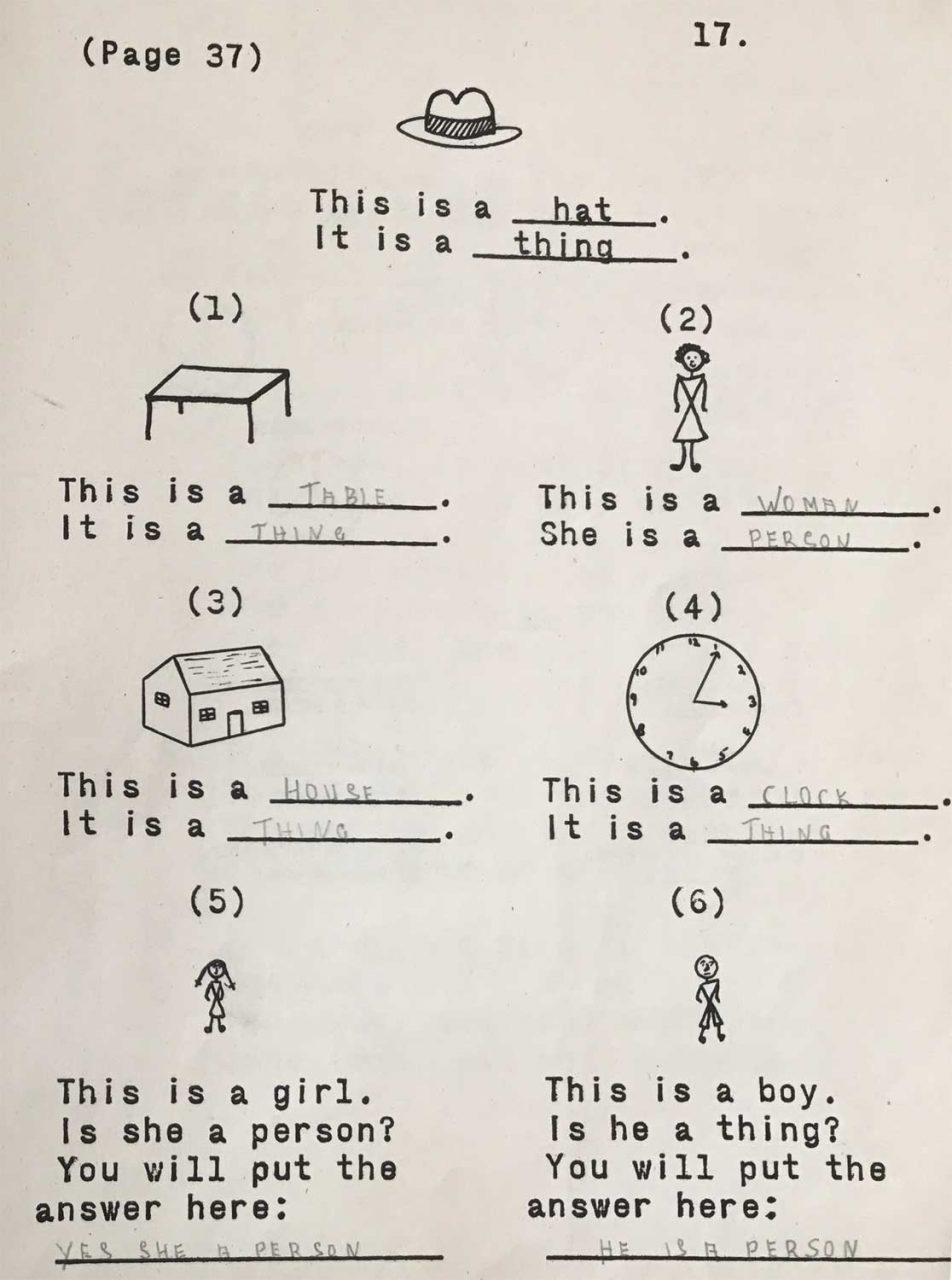

When my father showed me the eighty-page Workbook that he had been given on commencing his training at Maltby Colliery, my first thought on looking through its fill-in-the-missing-word sentences, the artless line drawings of ‘Mr Smith’, ‘Mr Brown’ and their respective families, was disbelief. Why teach foreign adults as though they were primary school children? Why would the National Coal Board have opted to teach 2,500 Italian would-be miners with an American English booklet that had stores rather than shops, iceboxes rather than freezers? In what way would the story of ‘Little Black Sambo’, the booklet’s final comprehension exercise, serve to bring about an ‘effective heightening in men’s ability to understand one another’?

A page from my father’s BASIC workbook

At this time, few post-war UK immigrants received any formal instruction in the English language. ‘To Help You Settle in Britain’, a booklet which the Ministry of Labour produced in 1948 for ‘aliens’ arriving via the European Volunteer Workers scheme, insisted ‘You Must Learn English’, but could only signpost its readers towards Local Education Authority classes and the BBC’s daily ‘English by Radio’ programme. The BASIC manual was better than nothing, and my father devoted himself to it.

Ogden and his collaborator – the noted literary theorist Ivor A. Richards – had come to the conclusion that ‘with under a thousand words you could say everything’. Ogden committed himself to creating a serviceable English shorthand that would help the expansion of international trade and consolidate English’s emergence as the lingua franca of science in the early 20s, but the marketplace for auxiliary languages was already crowded. Esperanto had claimed over a million speakers, and was being considered a working language of the League of Nations. And its rivals, Ido and Occidental, were fast gaining adherents in Europe and Asia.

Ogden was progressive in his politics and outlook, but his attitude to linguistic diversity was oddly parochial. As much as he welcomed the ‘elastic phraseology’ of American slang – ‘psyched’, ‘dope’, ‘then some’ – he was troubled by the slow demise of the ‘dead languages’ that were in his mind impeding all efforts for international peace and co-operation. In 1929, after several years research and experimentation, Ogden presented the first iteration of BASIC English in the journal Psyche. Here, according to Professor Ogden, was a survival mini-language that could be taught within a matter of weeks, to speakers from any linguistic background.

Ogden’s Orthological Institute soon began to publish BASIC versions of the bible, Homer, Plato, Joyce and Shaw, as well as a raft of popular science books. Sure enough, Ogden’s foray into ‘linguistic engineering’ snowballed into a bona fide cultural movement. Endorsed by George Orwell, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells and the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski, BASIC English undersigned the notion that world peace required the eradication of cultural differences and the creation of a new ‘supranational mind’.

Ogden’s efforts to convince the Colonial Office and Foreign Office of the advantages that BASIC offered over its rivals were repaid in in 1943, when Churchill’s cabinet announced that ‘definite encouragement should be given to the BASIC system as an auxiliary international and administrative system’. Within a few years, however, the tide had turned: the British council decided that BASIC was not the future of English language teaching overseas, the BBC lost interest, and Orwell’s growing unease with the idea of restricted languages had led him to contemplate the tyranny of newspeak in 1984. Why the National Coal Board looked to BASIC to teach American English to my father and his fellow Italians remains a mystery.

*

My parents settled in Frizinghall, the epicentre of Bradford’s Italian community, and stayed there until an argument between my mother and her unpredictable older sister, my Zia Lella, led to the sudden appearance of a four-foot high wall in the middle of our adjacent backyards. The wall was the beginning of a major change. Without any real explanation, we quickly moved to a semi-detached house in a predominantly English neighbourhood, and for the first time I found myself in kitchens that smelled of butter and wet dog; in lounges filled with porcelain figurines and Silver Jubilee memorabilia (no plumed Sicilian carriages or prints of Padre Pio); in lawned gardens without zucchini and spinaci; on cricket fields with boys who never tired of asking, ‘go on, say summat in I-talian.’

Other than a newfound respect for queuing, my parents would remain defiantly unintegrated, only speaking English to neighbours, or when out shopping. At home, we watched films in which Rossano Brazzi charmed American tourists, and guffawed at Totò, the great Neapolitan actor-clown. We played scopa and briscola. We listened to the yearning, almost womanised tenor of Claudio Villa, ‘the king of San Remo’. And on Saturday evenings, before we headed out to see friends at the Sun Street Italian club, I would anoint myself with two splashes of Pino Silvestre, as though it was my patriotic duty to carry the whiff of Italy’s leading pine-and-juniper cologne into the streets of Bradford.

The Italy I knew as a child – and the Italian – was distinctly Southern, and much of what I came to know about il sud was not from my parents or language classes, but from the dog-eared copies La Gazzetta del Mezzogiorno which eventually wound their way into our house. I could by this time read fluently. The country was reeling from the Red Brigades’ kidnapping and murder of former Prime Minister Aldo Moro. The South was, I discovered, in the grip of an organised crime wave led by the Neapolitan Camorra, the Calabrian ‘Ndràngheta and Puglia’s newly-formed Sacra Corona Unita. On every other page, there were reports of heroin overdoses, dynamite attacks on police barracks, letter bombs sent to magistrates’ homes. There were kidnappings and heists galore. The bandits of old had, it seemed, traded their horses and rifles for Alfettas and sub-machine guns. Some of them claimed to be enemies of state, but on closely studying their recidivist smirks and thousand-mile stares I guessed that most of these self-styled ‘freedom fighters’ were out to fill their own pockets.

On Sunday mornings, I began to ask my father’s friends – men with booming voices and missing fingers – what they knew about crime and banditry in Naples, Syracuse, Caserta and Frosinone. At after-school Italian classes, I tried to quiz Professore Pucci, our new Italian teacher, on the bloody history of brigandage. Feigning ignorance, Pucci shook his head and directed me back my textbook. Several weeks later, I rephrased my question and he asked if I would like to conjugate some irregular verbs. Then, quite unprompted, he slurred grumpily, ‘If you want bandits, try Apuleius and Boccaccio’.

By the time I had learned all my irregular verbs, I was on the brink of giving up on Professore Pucci’s Gradgrindian lessons. I was bored with rote-learning, and overly sensitive to the limitations of the Italian idiolect I’d acquired. When a visiting cousin described our lounge as accogliente, cozy, I had never heard the word before. Though I was familiar with the word sgarbato, meaning rude or ill-mannered, I had to wait until my teens to hear my father’s best friend, Michele Siciliano, use it’s opposite – garbato. And when Professore Pucci asked our class how to say that we had been sick, I alarmed him by saying ‘ho rovesciato’. The verb rovesciare was not polite, he explained. Only an uneducated Italian would, he went on, use the verb in this way. ‘Yes, that what my parents say, that’s their language,’ I said, looking around the class, as though I had exposed his true missionary agenda.

The first time we flew to Italy as a family seemed like it would be another turning point in my linguistic ‘repatriation’. Before the summer had ended, I was rolling my ‘r’s, moving easily between dialect and formal Italian. Yet American English was not easily avoided. This was the early 80s. As MTV and the high-five crossed the Atlantic, my cousins were singing along to Pink Floyd’s ‘Another Brick in the Wall’, they went out ‘shopping’, wore T-shirts emblazoned with proclamations such as ‘I Like Go Fishing’, took ‘picnics’ to the beach, made plans for the ‘weekend’, and began to relay ‘gossip’ which could sometimes provoke ‘shocks’. More confusingly, a number of so-called pseudoanglicismi, English terms used out of context, now entered their daily language: ‘footing’ was jogging; a ‘ticket’ was a prescription.

Not long after after returning to my Italian classes, Professori Pucci shook his bald head and pointed out that I had picked up a brutto vizio, a bad habit: I was using the past historic to describe recent events. I was not to say ‘lui mi disse’, he told me, when referring to something that someone had told me only days or weeks ago. I took this badly, and decided not to continue with my lessons or sit my GCSE Italian. ‘Basta’, that’s enough. This was was a second bad habit that I had acquired: a talent for barely-slighted enmity.

My relationship to the Italian language has since moved through various phases. In my early twenties, I studied in Florence, undertook academic and commercial translation, and, intermittently, spoke and wrote to my parents in Italian. When my daughters were young, I taught them to count, to recite the days of the week, and tried to holiday regularly in my father’s hometown. More recently, when visiting my elderly parents, I have fallen into the role of interpreter, dutifully explaining to my children what i nonni are saying when they forget to speak in English.

These days, I look back on Professore Pucci’s efforts to open a doorway into formal and literary Italian with mixed feelings. His repeat-after-me pedagogy, his zero tolerance for interruption, his refusal to reveal anything of himself, did not endear him to a class of thirteen to fifteen-year-olds that had been for the most part press-ganged into his lessons. Yet whatever his shortcomings, Pucci was a grammatical purist, a lover of puns and wordplay, who grasped something that Ogden and the disciples of BASIC English did not. It was simply daft to claim that 90 per cent of the work of the English language could be achieved with 850 carefully chosen words, a travesty to believe that any pocket lingo would turn my family into ‘supranational’ citizens of the world.

All photographs courtesy of the author

Cover photograph caption: My parents (front right) and their friends, 1956