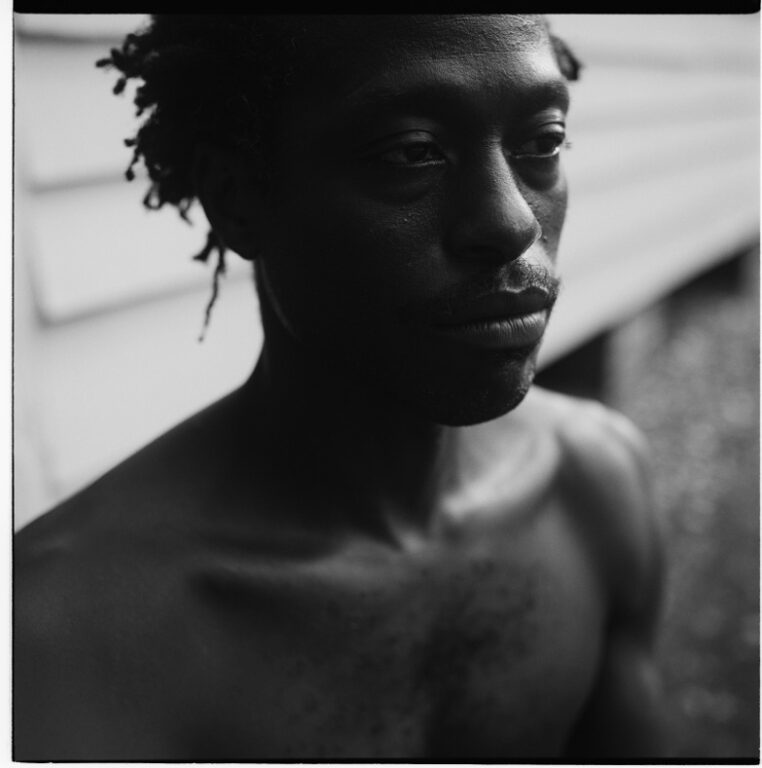

Sometimes, I make promises to myself that cannot be kept. Yet, I make them out of some hard-to-articulate principle, one that is quite clear in my mind. It was clear to me as I descended through the night sky into Charleston, South Carolina, the land below me fields that my foremothers and forefathers planted, harvested, chopped and picked whatever would come from its soil either as sharecroppers or enslaved peoples. The promise I made to myself while descending into the dark of Charleston to visit the McLeod Plantation to give a poetry reading in June 2019 – not to be overwhelmed.

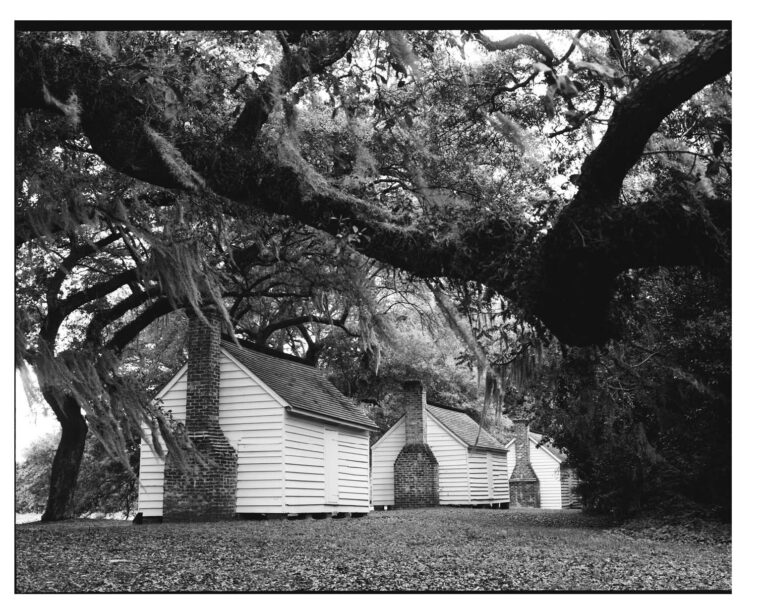

I was there to trouble history, not to be troubled by it. Or, if troubled by history, not to be made an incomprehensible mess by it. If there was any disturbance to be done, any razing, it would be of the former plantation owners moldering in their graves and afterlives by putting my Black body where they never intended it to be – giving a poetry reading on the grounds beneath a canopy of trees, a cotton field that refuses to bear cotton behind me, the white clapboard cabins the former enslaved bunked in to my left, the Georgian-style plantation house with its large white columns and wraparound porch in front of me.

Disturb, disturb the bones, terror and trauma of history. Or at least that’s what my host, Katherine, thought we were there to do and said as much when we sat on rocking chairs on the gray-painted veranda of the big house earlier that Sunday afternoon awaiting our tour of the grounds – the gin house, the dairy building, the cabins, the carriage house. She remarked how disturbed the last owner, Mr McLeod, would have been to have a White woman and a Black man leisurely sitting on his porch on a Sunday afternoon. In front of me, I saw it – the whole scene, all of the former owners of the plantation, standing there, silently staring at us, angry at our consorting in this fashion on a Sunday, the Lord’s Day, no less. It made me smile, and I rocked a little harder in my chair, leaning farther back in it as if trying to relax into the thought of it, into the perturbance and all those angry faces in their bonnets and long white linen Regency dresses and one-tail frock coats and ruffle-collared dress shirts and riding boots and whalebone corsets and petticoats and deep, deep chagrins and rage, rage in their small eyes, all of them watching us.

But then the wind. The wind began to pick up and drove the dirt from what was once a cotton field into my eyes, and the clouds gathering overhead seemed to be trembling toward rain, and our guide, Shawn Halifax, came out of the big house and ushered us into its interior, as if to say we will start here.

I don’t remember much about the plantation house other than the second floor was off limits, and the first floor had these large rooms that smelled like the old colonial homes that I had entered and visited as a child growing up in southern New Jersey. Like South Carolina, New Jersey is one of the original thirteen colonies of North America, and, often, the towns and boroughs are older than the nation itself, so one gets used to going into old homes that are now libraries and historic monuments to observe some obscure bit of early American history on field trips in grade school. Or to visit a friend’s family who now lives in one-half of an old house originally built in the eighteenth century. Or the local library in Mount Holly, New Jersey, once the Langstaff family mansion, now a library with a hedgerow labyrinth behind it that my sister and I would wander through during the summer after checking out library books. The books in plastic bags banging at our sides, we ran through the tall, green corridors of the maze. The traffic outside the labyrinth inaudible from within; so inaudible that you felt as if you might truly disappear and possibly never be found. Even the birds, the sound of the birds in the trees that overhung the labyrinth seemed never to make it down into its corridors, which unnerved my sister. I would always have to backtrack to find her, hiding somewhere in the labyrinth refusing to move.

We moved through the big house, and I kept drifting, drifting back to New Jersey, where I thought of a friend’s house in my hometown, a house formerly owned by Quakers through the eighteenth and nineteenth century, a house that once harbored part of the Underground Railroad in its basement. The smell of that place was the smell of the McLeod Plantation. I know it was the wood, humidity in the air and age of the house, but I couldn’t help but think of termites gnawing at the bones and boards of the house and the Black people walking on top of those old bones or huddled beneath them, underneath the work of the termites.

Something about the big house seemed like smoke, or it existed as smoke, as something disappearing, something which was not there though whenever I stepped in it was firmly and treacherously there. While touring the house I kept looking out of the windows to see where we were in relationship to the cotton field, to the clapboard cabins, to the gin house.

It was the gin house that I had been meaning to get back to, the brick and chicken wire, the darkness, the old beams holding it all up at the bottom of a short hill. Though I was receiving my official tour on the day of my reading, I had been to the plantation the day before, walking the grounds with Katherine, my host, who thought that I might want my own time at the plantation and the unmarked graveyard across the street. She was right. I wanted my own time there, to map and mark my own course across the grounds, to wander and see and touch and stay. Stay with whatever and whoever might call me. And, it was the gin house that called me, and no matter where I wandered, I always returned to it, to this small detail among the brick and chicken wire and darkness. A child’s fingerprint. A child’s fingerprint in the brick.

At the McLeod Plantation during slavery, children who were not yet old enough to work the fields, or in the carriage house with the horses, or in the plantation house as servants, were put to work turning over hot bricks to dry after they had come out of the kiln or pulling them out of their molds before they went into the kiln. I imagine the children, in their potato-sack and burlap-bag clothing (if any clothing at all) clambering and climbing over, up and down rows of brick sitting in the sun, the brick hot against the tips of their fingers, the children moving, moving over the brick and the heat from it burning the pads of their feet, their wrists and fingertips. Or, did they fashion themselves a glove, some sort of mitt to help staunch and rebuff the heat?

I shouldn’t do that. The evidence – their fingerprints in the brick – shows they used their bare hands. And, with my bare hands, I wanted to lay my finger in the indentation left in the brick, but should I? All weekend, I returned to the same brick and stared – the gin house that once held all of the harvested cotton from the plantation was reduced to this one brick for me. You might think my hesitation unnecessary, even overly cautious, but hear me out. My hemming and hawing at touching the brick had less to do with the preservation of the physical structure of the gin house, less to do with whether the oils of my hand, my finger, would bring about the rotting or degradation of the brick as material. My hemming and hawing had everything to do with the limits of empathy, catharsis, historical reckoning and the ease with which we think we salve the open wounds of history and the ongoing catastrophe of racism and discrimination in America with personal epiphany and gesture, with tears and the gnashing of teeth. And besides, I had made the promise to myself not to be overwhelmed.

If I allowed myself to be overwhelmed, what would I be missing? What might my focusing on my own tears and heaving, my inconsolability obscure? In other words, how might I miss seeing the child whose hand had to turn this brick, this child who was not supposed to be seen or remembered; or, if remembered, remembered in the way that property is remembered, as another line in a ledger, as useful or as useless as a shovel or a hairbrush, as something outside of history? How might my focusing on my inconsolability replace this child’s absence in this neat body-swapping, which brings me back to my hemming and hawing, my desire to touch the brick, the fingerprint in it. What would sliding my finger into the indentation erase, overwrite, make opaque? What is gained in putting my hand into this lacuna of history?

The child does not move closer to me if I touch the brick. Their ambitions, their love or disdain for corn, for syrup, for the night sky or the feel of their mother touching their brow are lost in the flotsam of history, of genocide. It is unrecoverable. And, as an American, I must reckon with this absence without seeking to escape it through the catharsis of weeping, through merely placing my finger into this hollow in the brick. Because my finger does not address what allowed the brick to be made, does not address that this brick (which is a synecdoche for a certain form of structural inequality and labor and death) still holds up a gin house, still holds up the fraudulent and disingenuous storehouses of American wealth. Our collective fingers pushed into the fingerprint of the child, our photographing of it, our placing our head against this wailing wall, our own wailing does not tear down the walls of this house.

Nothing easy. Nothing without work. Which is what I was at McLeod to do – to work, to trouble history, which is quite un-American. We Americans like to leave our history like we treat our garbage – thrown down a chute into some invisible darkness or left at the curb to be carried off by men and women who wave at our children from behind beatific smiles while standing on the thinnest of platforms, standing precariously close to a blade crushing and cutting our sweltering and stinking waste, the trash truck’s maul churning, churning our garbage as it moves off and out into the distance. And we go back into the house; we move on. ‘Move on’ is what this country wants Black folks to do. Touch the old wounds, the old brick, cry a little if you must, and shut up about it.

But the old wounds are not so old. They have not been closed or dressed. In fact, some of the old wounds, most of the old wounds, are raked and pressed and torn at again and again with the reinvention and renovation of the old lash. Though our children are no longer on plantations, turning over hot brick, they are still being deracinated and forced to bear unspeakable acts that call back to and echo the disciplinary technologies of slavery. In Arkansas, a White schoolteacher recently forced her Black kindergarten student to clean a toilet stained and drenched with feces with his bare hands. Slave breakers and masters often forced enslaved people to drink urine and eat excrement as ways of subduing and subjugating them. I do not recount these horrors to be salacious or to muck about in spectacle but to exemplify that the disciplinary acts that have been used historically to make slaves have been recalibrated and reinstituted in our public schools, which are responsible for making citizens. What is that teacher making in that moment? What is she teaching us about the nation and what we love and whose children must be subdued and who does the subduing?

The Black child in Arkansas in 2021, the children on the McLeod Plantation in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, worlds apart, face, faced annihilation, and here I am bringing my mouth and hand to it. Something in me wants to touch all of this despite what I know or think I know about the irreconcilability of touching the brick, despite my potential touch making nothing happen, despite my oath not to be overwhelmed, not to put my body in the way of history and its lacunae.

Despite my oath, I touch the brick. I touch the fingerprints. I photograph them, but I know I’ve done nothing in the touching. I’ve reconciled nothing. There’s no relief in the touching, only the sense that I’ve transgressed my oath to myself, but the transgression is necessary because I affirm that yes, I’m alive. I am more than a mind, more than a reckoning, more than a lofty principle that evacuates and voids the body of its sentience. I touch the fingerprint because I am trying to get beyond the imposed limits of my Black life. Which is to say I’m trying to get to life and that more abundantly. A life beyond what history can imagine. A life beyond the gates and brick and lash, where the velocity of the dead’s ambition is in the wind – is the wind.

The tour of the plantation, my memory of it, is slipping from me. I remember standing at the carriage house with Shawn and Katherine discussing what we would do if it rained and the poetry reading could not be held outdoors at the edge of the cotton field. However, I don’t remember anything about the carriage house, its function, its history, the significance of it in the everyday life of the plantation. I was still distracted, not only by the child’s fingerprint in the brick but also by the story of the plantation and enslaved folks who resided in the small white clapboard cabins at the edge of it at the end of the Civil War.

Here’s the story as it was told to me. The Union Army established themselves on James Island, a tidal island separated from downtown Charleston by the Ashley River, at a far edge known now as Folly Beach Word, somehow, made it to the enslaved folks on the McLeod Plantation that if they could reach the Union Army stationed on that beach then they would be free. But they had to journey tens of miles of woods and wetlands infested with Confederate troops and encampments to get there. A group of enslaved Black folks ranging in age from ten months to eighty years struck out into the forest and swamp at the edge of the plantation at night. Somehow, they made it undetected through the woods, to the beach, to this New World or at least their version of it.

Since hearing of their flight, their journey out of slavery through the pines and stinging insects, into the marshes and wetlands, I imagined or tried to, at least, imagine what that flight must have felt like, moving off a plantation that you possibly have never left before, walking toward the Atlantic, then coming upon that big body of water. A body of water that you possibly crossed a few years before in the hold of a ship in shackles. Now, ironically, you must walk back toward it to gain your freedom. And, if you haven’t crossed it before, surely you have heard of it, maybe learned of it, of torturous trips across this abyss. Or, maybe you haven’t. Maybe, the water lapping against the shore and rolling out to more water is your first glimpse of freedom. To see out onto the water, out onto its largeness must have felt simultaneously like an apocalypse and an act of creation. I can’t help but think of moments like this as radical imagining. These folks walking off that plantation had to imagine into several abysses. The abyss of the woods, the abyss of the water, the possibility of capture, disappearance, liberation. Abyss, abyss, abyss. Moving out into those many abysses required what the old parishioners in the Pentecostal Church I grew up in called ‘stepping out on faith’, which is a kind of art and artistic practice. ‘Stepping out on faith’ is the practice of inhabiting the invisible, moving off feeling and sound, negotiating the future not by sight but by touch even if what must be touched has not yet arrived. This might not make sense, but you might have to expand what you know of sense – what it is to feel, what it is to come to something, to come to something like freedom – to touch what can and cannot be felt. This feeling for the future is a matter of art, the art of self-making, of fashion and fashioning a life in bondage and a life out of it. This is not just the King having no clothes on, and strutting down the street in his birthday suit, this is the people rejecting the King’s story altogether, taking to the woods with what they can carry in their hands and building their own thing, their own sound, their own story, sewing their own clothes. The ‘it’ here is freedom – the making and inhabiting of it. Allow the King to bear whatever suit – real or imagined – he wants, without a gawking or judgmental eye because the people are no longer concerned with the kingdom. They have left for the future, stepping out into the abyss.

‘Stepping out on faith’, stepping out into the abyss of escape is about occupying a nonexistent form and turning that into fact. In the case of the enslaved on the McLeod Plantation, the fact was freedom; the form – that it existed, in the middle of the catastrophe of slavery. I can’t help but think of Frederick Douglass who wrote in Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, his first slave narrative, that after fighting back and whipping the slave breaker Edward Covey that ‘however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact’. Douglass understood that freedom did not exist in some amorphous future but could be occupied in the middle of his enslavement. And occupying that freedom required a willingness to do the unthinkable, the ungovernable – to step into the sublime – to fight. I would caution us not to sequester fighting to only the realm of pugilism and combat. Fighting can take a whole host of forms. And running away, stealing away, which is a type of silence, is one.

Where was I? Shawn, Katherine and I were somewhere in one of the white, clapboard slave cabins lining the drive that dead-ends at the big house. The cabins, in their quietness and vacancy, reminded me of mourners, their head bowed, as if to offer a counterargument to the line of trees arching over them leading toward the picturesque plantation house with its stately columns. It was as if in the cabins’ hush they were whispering, ‘don’t be fooled by this constructed beauty. What lies ahead, that big house, isn’t beauty. It is actually the absence of beauty.’ Or as if the quietness, the curated dilapidation were saying something about what it takes to build a big house and a plantation – amnesia, moral decrepitude and death.

Regardless, I was somewhere inside one of the cabins. An outline of a cross was high on what I would call the front wall of the cabin, a wall where a pot-bellied stove might have stood. Stenciled along the other walls were scripture, passages from the King James version of the Bible, but the sun had faded the passages so that they were difficult to read. I squinted and tried. Shawn explained to Katherine and me that this particular cabin used to be a church; that, in fact, the descendants of those enslaved on the plantation had lived in the cabins – the slave cabins – into the 1990s. I was – and am – stunned by this fact, and shouldn’t be. That Black folks lived, married, loved, raised children, prayed, worried in these cabins in some form or fashion through the Civil War into the twentieth century up to Jim Crow and past Jim Crow and the Civil Rights movement and the Berlin Wall falling. They lived in these cabins during the assassinations of Patrice Lumumba, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. They lived in these cabins well into the first Bush administration, the LA Riots, the first Gulf War, the beginning of the tech boom. These cabins not much bigger than two walk-in closets at best. These cabins with no electricity or running water. These cabins Black folks rented – rented! – in hopes of buying from the descendants of their former masters, working the same land as sharecroppers that their ancestors worked as enslaved. They had to pay for the pleasure of this.

I was overwhelmed but trying not to show it. I was trying to make it through the tour without breaking down there in the dark heat of that cabin, but the day, the heat, the history started to press against me; was all moving inside me, fraying me, and it wanted out. Or, at least, wanted me to register it, touch it, without some hard-to-articulate principle guiding me through the flotsam and jetsam of it. And, I wondered if it was time to relinquish the promise that I made myself – not to be overwhelmed – while taxiing on that dark runway, whether it was a worthwhile promise at all. Should the promise be scrapped? Or, had it offered me a reprieve, a moment to sit in the complexity and largeness of something like three hundred years of Black people forced to work and love and make do on a piece of land? Had my promise allowed me to contend with the ongoingness of that catastrophe, an ongoingness that was still there in the cabins?

Yes, laudable to want to face history without centering the self, to allow the past its full body without obscuring it with my own, but my body couldn’t be ignored because my body was sign of the ongoing and uninterrupted phenomenon of Black folks trying to make life in and despite America – sign in the sense that we never stopped making family, never stopped making song and sound and moaned and thought and read and ran, even when we were told not to. We compelled ourselves toward life and that more abundantly despite the plantation and prisons, slave patrols and vagrancy laws, Black Codes and cabaret licenses and redlining and apartheid and the police and counterintelligence programs and the FBI surveilling our writers, artists and movement makers and Tuskegee Experiments and sterilization programs aimed at Black women and their uteruses and reproductive rights and Moynihan Reports and bombings of Black churches and the bombings of private Black citizens by city governments and restrictive covenants and telling us we can’t wear our hair how we want and the disbelief, the constant disbelief that we are unable to breathe.

I was able to make it out, make it outside the cabins without breaking down. The clouds overhead roiled and pitched, covering everything in gray. I looked out onto the cotton field for a moment of relief, for something other than the heaviness of that dark. The wind slunk across the field tossing up wisps of dirt. And my mind, like my eyes, drifted into the woods just beyond the edge of the field, and I was thinking again of those enslaved folks journeying away from the plantation out to the shoreline at the end of James Island. Had they looked back at what they were leaving – the cabins, the field of cotton, the plantation house? Or had they run into the pines, concerned only with what was out in front of them? Did any of the children whose fingerprints were in the bricks of the gin house go with them? I imagined some looked back and some didn’t. But if they left at night, what would they have to look back upon? Then, I remembered – no, not remembered, I was not there so I can’t remember – more so realized – realized in a way that feels closer to memory than epiphany – I realized that some had to leave something behind – a child, a mother, a favorite tree, a memory – something that could no longer be touched. I wasn’t overwhelmed with this thought as much as I was full with it, standing there in the door of that cabin, looking out into that cotton field that refused to bear cotton.

I thought I had made it through the gauntlet of history and terrible feelings and come out on the other side, a little weary, ruffled and singed but nevertheless whole. The white chairs for the poetry reading sat in neat rows beneath the canopy of trees next to the cotton field. The sky had decided to hold on to its rain, and I was turning my mind toward what poems I would read that would be in conversation with the landscape and the history of the plantation. Maybe a poem about Emmett Till’s body coming to rest next to a dead horse in Money, Mississippi. Or a poem about running through Austin, Texas, being followed by a White man who decided to yell ‘nigger’ at me.

But history was not through with me. And neither was the tour. Shawn motioned for me to follow him to the back of the cabins. We stepped through the unevenness of the underbrush and stood there in this little copse of trees, our feet entangled in some sort of creeping vine, kudzu perhaps. Around us, the ground undulated in what looked like little burial mounds, kudzu completely covering the little hillocks. I asked, what was this. It felt as if Shawn had brought me to something that was not on the official tour. It felt as if we had stepped into a broom closet or crawled into an attic, into the rafters of some great hall and were touching the bones of something, the bones of God perhaps, the bones of something that was never to be touched.

When the city decided to turn the plantation into a historical site, according to Shawn, they emptied the cabins. Tossed everything out. Mattresses, clothes collected by the church for charity, hymnals, Bibles – anything left in the cabins by the descendants of those that once sharecropped, worked and were enslaved on this land was beneath our feet. It was all beneath our feet.

I don’t remember if I turned away from Shawn, but I do remember crying, walking out of the trees, walking back toward the cotton field and watching the wind blowing over it. Everything was present, too present – the child’s fingerprint in the brick, the big house, the enslaved running away from the plantation to the edge of the world, the old church in the cabins, the little death mounds of discarded clothes. I wanted to bear it all without being overwhelmed, without crying, but I couldn’t. It was silly of me to think I could.

My tears were not merely my version of a belated elegy for the folks that lived and worked and died on the plantation. I was in awe at Black folks’ imperishability. That despite the several hundred years’ attempt to alienate and divorce Black people from their bodies, from creating loving and meaningful bonds with each other, despite the nation’s many attempts to extinguish Black folks’ desire for freedom, for touch, for intimacy, for nearness, Black people consistently and constantly slipped that yoke, troubled their trouble until it yielded something else. In the middle of disaster, we made the unimaginable – joy. Political will. Mutual aid societies. Churches. Women’s leagues. College funds. Clubs from Nowhere. Fraternal orders. Panthers. Deacons for Defense. Washing machines. Vacuums. The Blues. Jazz. Rock and Roll. The Stanky Leg. Funk. Dat Dere. And Dis Here. If there’s anything worth doing in America, it was because some Negro got near it and touched it – put their shoulder, mouth and mind to it.

We troubled history even as history troubled us, even as history wanted to keep us outside of it. This, this, this was all in front of me, touching me, moving through me. It was in the wind and beneath the wind moving over the cotton field that refused to bear cotton.

There beneath the umbrella-ing oaks, I wept and watched the wind warp and bend across and over the nonexistent rows of cotton as if the wind were remembering the bodies that once stooped over in this field, separating boll from white, shoving it all down in a croker sack before drifting to the next boll and repeating. It was as if the memory of the workers was still there in the thick marsh air. Or was it their presence, the spirit of the formerly enslaved, the trace of their physical selves tethered to the land, to the landscape, even after their deaths. Or was it the motion of their work haunting the present? What was making itself known? I couldn’t tell. All I could do was feel full and cry and watch the wind work over the dirt, the dirt lifting into plumes of what I was sure was memory shattering in the air as the wind raised it, raised it from the earth.

What was I facing? What was I witnessing? And who was I, not known for visions, to see what it was that I was seeing? I had a sudden impulse to record the wind – not the sound of it but its motion, the dirt kicking up in the field. I wanted to make a short film, wanted others to see the wind moving over the shoulders, hands, backs and faces of the formerly enslaved, wanted others to feel and see this history, in these almost invisible gestures made by the wind. In this way, I wanted companions, co-conspirators, a record of this history because the wind was acting as history, making known the lives of men, women and children who may have been no more than a line in a ledger; the wind remembering the arch and curve of their backs, the angle of their bending; the wind acted as an archive of the dead’s ambitions – was the dead’s ambitions. Something about witnessing the wind in this field felt liberating. The air moving, moved because of the dead. I was beyond science and scientific explanation of the wind – the uneven heating of the earth by the sun and the earth’s rotation causing air to move. The wind was under the auspices of a different science, a science that bears its fact and truth not through observable data only but through movement felt along the skin, the dead’s presence still in a field long after they are no longer in the field. The dead walking and working in the air, walking with me, wanting me to know they were still there, are still here – alive and living. Working. Working after death, working the day beyond their coerced labor. Working life into me, into us despite the trials and tribulations at every city council and school board meeting and legislative session, despite the surveillance of our communities by the police, despite . . . despite . . . despite . . . The dead are in the field toiling with us.

But then came doubt: would this be enough? Would a film about wind carry, would it matter to Black folks that are facing voter disenfranchisement in Georgia, police brutality in Texas and Minnesota and all over this vast land, gentrification in Charleston along the Gullah Rivera? Would looking out into a field, looking out on what might or might not be moving, would that matter? What is the place of opacity in art that seeks to plumb the long and difficult history of the erasure of Black folks in this country? Born in 1980 and therefore a grandchild of the Black Arts and Power Movement, a child reared on vinyl records of Malcolm X’s and Martin Luther King’s speeches playing on a wooden console that sat beneath the large picture glass window, a place of honor, in my grandmother’s living room, I worry about the efficacy of what might be called abstraction, making a film that does not explicitly answer the call of what Black Power scholar and artist Larry Neal defined as one of the central concerns of Black art and artists – ‘to speak to the spiritual and cultural needs of Black people’.

But the field is – it is speaking to the spiritual and cultural needs of Black people, but it’s not doing so explicitly but implicitly, imaginatively one might say; another might say spiritually. The field’s refusal to bear cotton is not merely symbolic. The field is offering us a type of vision, a pronouncement of the future. It is as if the earth is reading history, reading the history of the land and oppression that has transpired upon it, and has decided to quit, to go on strike. The earth, there, is reading the gentrification of the Gullah and the sea islands off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina, reading the problem of run-off water from development projects in the area, and it is saying ‘no más’. No more. No more. It is as if the cotton field in Charleston anticipated the coronavirus pandemic, the world shutting down, and now is asking us: what should we refuse, what should we break, what should no longer work?

How ironic is it that the crop that ushered America into the world economy will no longer grow in this American field. It is as if the field anticipates America slipping from the pedestal of world power. I can’t help but think of Martin Luther King’s fear that he was ‘integrating his people into a burning house’ because of the US’s commitment to injustice, violence, and oppression not just at home but abroad as well. Maybe, this field is also articulating the burning-house-ness of America. An America in decline. A fallow America.

There is something in this field, in watching the wind move in it. And being moved by it. It offers us a type of imagining, a way of seeing, of knowing which reminds me of the poetic (the poem, the lyric) – something simultaneously tied to the past yet free of it. A renouncement that is also an enactment. An ending that is also a beginning. Just like the lyric poem, the field does not submit itself to narrative and its attendant discourses of time, which is unfortunately how we’ve come to understand change, particularly political change. Everyone wants a narrative – beginning, middle and triumphant end; some happy future that derives from this ignominious present. But what if history is a lyric? What if the freedom you seek can’t be narrated in some linear or teleological fashion? What if this field, the watching of it offers us the space – both literal and meditative – to steal away, plan, study? What if in the watching, our minds drift, and we find some answer to how to get medicine to our sick family? What if we drift and the field brings us back to some incident of pain, of sorrow that we have yet to reckon with? What if our freedom, some instantiation of it, some idea of it, is in watching wind move over a field?

And, there in the wind, in the dirt, the memory of the dead moving off into the pines behind the field. There is no definitive narrative to escaping, to freedom. It is – only is.

All photography © Rahim Fortune

Film Credits

Director – Rahim Fortune

Cinematographer – Adé Randle

Editor – Ayodeji Gunlana

Composer – Tito Rovner