The reason I came to Joshimath was to see the houses that had developed cracks. I had read reports about a sinking Himalayan town, and understood, in a vague way, that the town’s fate was tied to poor development and ecological disaster.

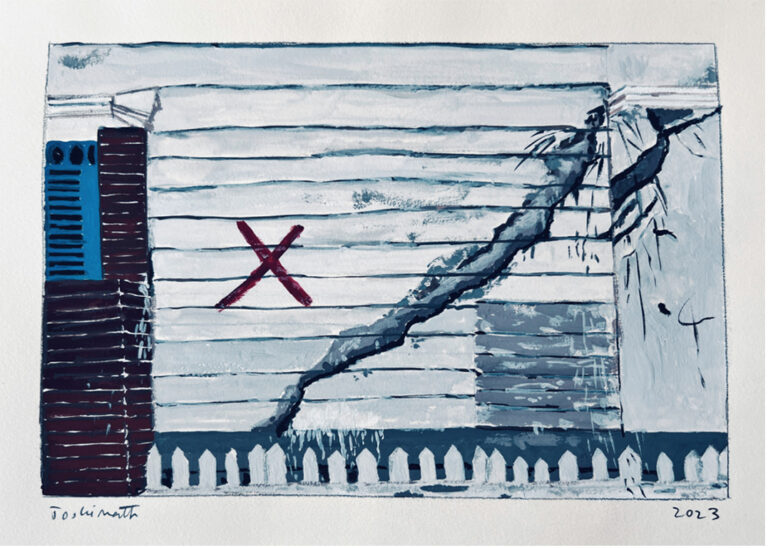

Standing in front of the collapsed or tilting houses, the reality was plainer, more dramatic, and devastating. The damaged homes were identifiable not just by the cracks in their walls, or the red Xs that the government painted on them, but also, even from a distance, by their air of desolation and abandonment.

Atul Sati, a local inhabitant and an environmental activist, told me that the first cracks appeared in a row of houses towards the end of 2021. Now, by government estimates, at least 868 homes are affected. Sati took me to meet families whose homes had been destroyed. Ashish Joshiyal, a young man with his hair in a pony-tail, said that a thin crack became visible outside his family home in the beginning of January last year. The next day, the crack had widened. So the family moved out, and have been living in a relief camp run by the army. Behind Joshiyal I could see how the family temple had snapped in two, the red dome fallen back while the rest of the structure slid forward. His family owned an orchard, and fruit-trees were visible in front of the ruined structure of the home, apple, orange, apricot, plum – but there too the ground had slipped. The earth was sliding down toward the Alaknanda, the headstream of the Ganga.

The plight of the people in Joshimath has everything to do with the river. For the past six years or so, the government has been blasting the rock beneath Joshimath to make way for a hydroelectric dam. The idea is to create energy by diverting the flowing waters of the Alaknanda into a tunnel, where it will turn the blades of turbines that produce electricity. Sanjay Uniyal of the Joshimath Bachao Sangharsh Samiti, a community organization fighting to save the sinking town, explained to me what is involved in this process: for each blast, the power company drills 157 holes in the stone foundation a kilometer below the earth’s surface, the holes being 12 meters long and 6-8 inches wide in diameter. The holes are then packed with dynamite. Every 12 meters (or less if the explosion is not effective), the process of drilling and dynamiting is repeated. As a result of the digging of the tunnel, the situation now is such that, as Uniyal put it, ‘there is Joshimath beneath Joshimath’.

A 2023 study in Current Science blames what is happening in Joshimath on more than just the dam – they cite rapid urbanization, the obstruction of stream courses, and a lack of efficient domestic wastewater drainage system. The dangers across the region are clear: ‘the unscientific road alignment, construction of barrages and underground tunnels in the proximity of urban towns without any consideration of the geological fragility are amplifying the terrain instability.’ What this means in less academic terms is that unrestricted development across this fragile, mountainous area of the Himalayas is causing the ground to sink, which leads to collapsing buildings.

The reality of state capitalism is that it spreads devastation and calls it development. I was confronted by this when I entered the newly-constructed home of Dinesh and Puja Rawat. The lower floor was still under construction. The upper floor was finished, beautifully furnished, but already the walls were scored with hairline cracks. Dinesh is a primary school teacher. He said that for people of his economic status there could be no chance of building a second home – he had poured everything into the building of this one. People like the Rawats cannot sell their houses and move because their houses are already condemned. Every month, when Dinesh goes to the bank to pay his mortgage, he asks himself what he is doing, paying money for a house that he is sure will be demolished. As I was leaving, he showed me the door at the side of the house that he always leaves unlocked at night. That door is to the room where his boys sleep. If the house begins to fall, they can use that door to escape. I tried to imagine what it would be like living each day with the fear of losing your home. The certainty that it would happen eventually. I asked Dinesh if he and Puja talk of the problem and their strategies to deal with it. No, he said. If they talk about it, it makes them feel helpless and full of despair. But they make it a point to join the protests and speak at the dharnas organized to protest the government’s plans.

The Bachao Sangharsh Samiti has been agitating on the issue of hydroelectric power plants on the Alaknanda River since 2004 – long before work on the latest dam started. They are not the only ones protesting overdevelopment. Other activists in the Himalayan region are currently mounting campaigns against high-infrastructure railway lines and four-lane highways. These projects are capital-intensive, and though they bring huge profits to a few, they extract a much larger cost from the environment and for the poor who live in the region. The financial kickbacks involved in these government initiatives are common knowledge, and so large that there seems to be little serious political opposition. This is true even of development outside the Himalayas: critics are always pointing out how the government happily builds flyovers in metropolises rather than constructing primary schools to pull children out of poverty.

Atul Sati is a veteran leader of the Bachao Sangharsh Samiti, and told me of previous disasters on the Rishi Ganga. Not just once but twice floods on the river swept away power plants under construction and the laborers working on them. Sati described how unresponsive the state has been; all the memos he presented to the local officials and sent to the Chief Minister about the sinking of the town went unanswered until the protesting citizens led a torch-light procession and then blocked all traffic the next day on the national highway. The government then promised compensation for all those who have lost their homes – but only as a result of organized protest. What is still unknown is how much they will be compensated, and where, if anywhere, people will be relocated.

–

As I was driving away from Joshimath, my taxi-driver stopped for tea. The owner of the tea shop had his hands buried in mud. He was moving his small palm trees from the ground into a big pot. He washed his hands for a long time and then prepared tea for us. While pouring our tea, he casually informed us that the highway was closed a few miles down. He said that a portion of the road had been washed away. Surendar’s face took on a pained expression. He said that he had been wondering for the past half hour why there had been no traffic from the other side.

I asked the men how long these stops usually lasted. It will take a few hours, he said. I thought of the suite of ecological disasters that had swept through this region in recent years, the retreating glaciers, the flooded villages, the landslides and subsidence which seemed now to be everywhere. The havoc wrought by ecological changes is so enormous that it has seeped into popular consciousness as an expression of divine anger. A decade ago, the shrine of the goddess Dhari Devi was moved from the Alaknanda River to make way for a 330 MW hydel project; within hours an intense cloudburst passed through the valley, and a flood wiped away not only the hydel project but also the nearby town. Hundreds died. For many this was a clear case of heavenly retribution. The Ganga is a holy entity in the minds of millions, and power projects are protested not for their ecological impact but because they represent human hubris. One sign that we passed on the highway read: आज माँ गंगा उदास है / बुरा हो रहा उसके साथ है (Today Mother Ganga is sad / She is being treated bad).

How much longer did we drive? Another half an hour or a bit more? Then we reached the procession of stopped cars. During our drive that morning, we had come down from ten thousand feet to five thousand feet. It grew hot on the road and it was necessary to be in the shade. Surendar said to me that the line was now about five miles long. By now, people had hung wet laundry out to dry. Others were sleeping under trees. The Alaknanda flowed beside the highway and many of the stranded travelers had gone down to bathe or swim.

The afternoon turned to evening. I saw the stranded travelers playing cards, or watching videos on their phones, or taking leisurely walks holding cups of tea in their hands. I envied them a bit. There had been zero information from anyone remotely resembling a figure of authority, but it was known that a landslide had caused the trouble ahead. Machines were removing the rubble but more kept sliding down as they did.

I was angry. Literally across from where our car was stuck, a tunnel was being dug into the foundation of the mountains. I wondered how many others among the hundreds of cars and buses parked along the highway that evening saw the connection between our plight and the hydro-power project across the river from us.

The highway came alive at four in the morning. There were shouts and cheers. We had been stuck for sixteen hours. Immediately we were caught in a jam. Impatient drivers were trying to overtake and, to compound the problem, several of the vehicles on the road were without their drivers.

Yet, in fits and starts, we made progress. After rain and slow movement over a few miles, the road cleared. We were again driving down the mountain switchbacks. The familiar sight of Shiva statues and the wreckage of cars. By the time we reached Rishikesh the sun was shining brightly and I saw more than a few rafts on the water. We passed other construction sites in the river valley. Ugly gashes in the mountain side. The familiar blue tin roofs and white walls of the offices, the long line of excavator trucks, prefabricated concrete. Near Paoli, I saw a man step out of the mouth of one the tunnels being bored into the mountain. He was miniscule – it was a sublime, terrifying sight. It was only at that moment that I realized how enormous the tunnels really were.

Images © Amitava Kumar