Refuge

Bruno Fert & Nam Le

In a way, it’s a relief the people aren’t there. A human habitation may or may not be more itself with a human in it, but it definitely feels, to an observer, more . . . available. After the first photo in this series, which shows scores of migrants crowding a rescue ship’s foredeck, people are nowhere to be seen. Throughout refugee camps in Greece, Germany, France and Italy, there are only transient interior spaces, vacated momentarily – by the transients momentarily stationed in them – so someone can step in and take a snap.

That someone is Bruno Fert. And he knows something about invoking human presence through its absence. His previous series, Les Absents, portrays the remains of Arab villages depopulated after the founding of Israel; these are haunting photographs, suffused with the ghosts of fled lives – more than 700,000 lives – driven out and denied return.

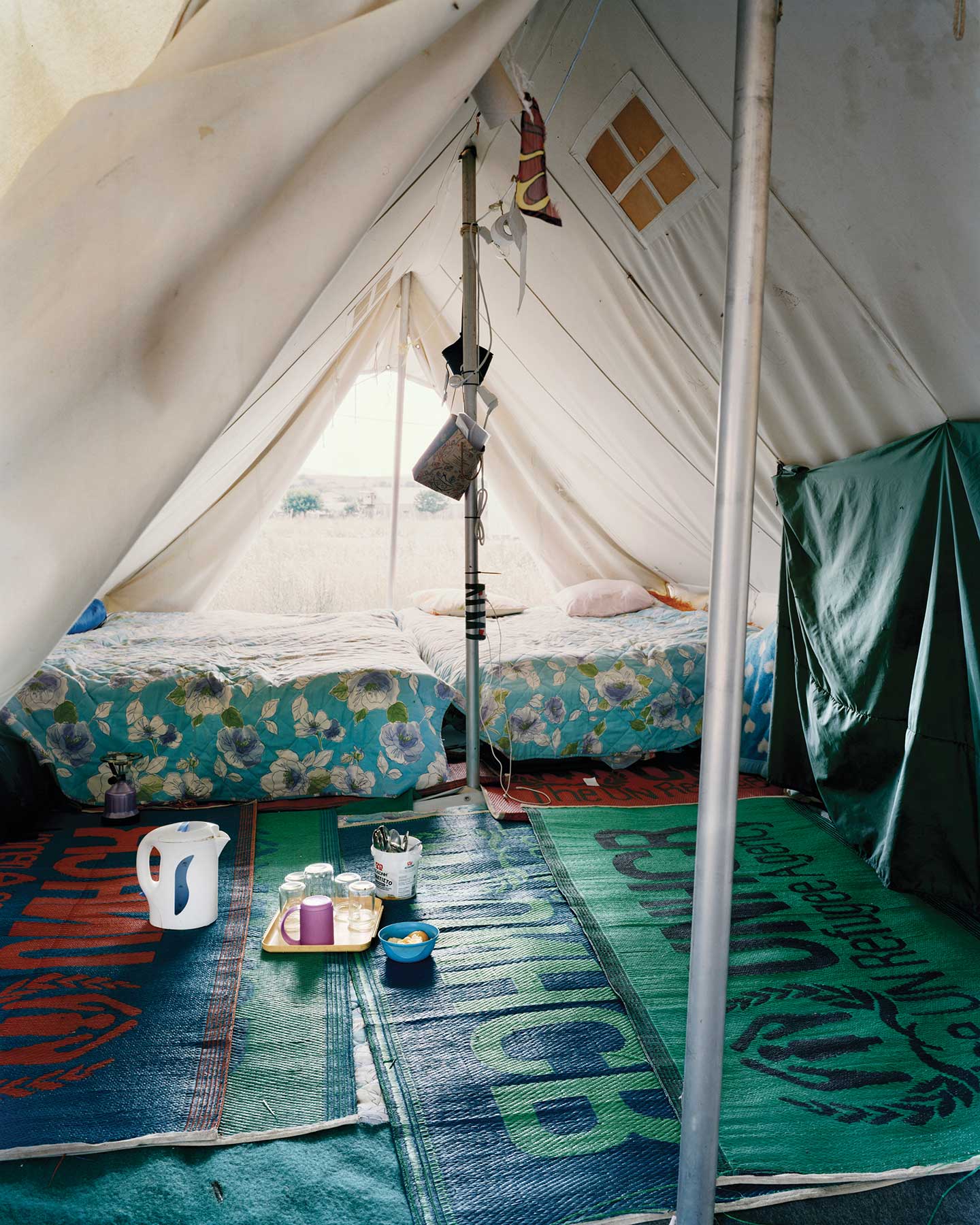

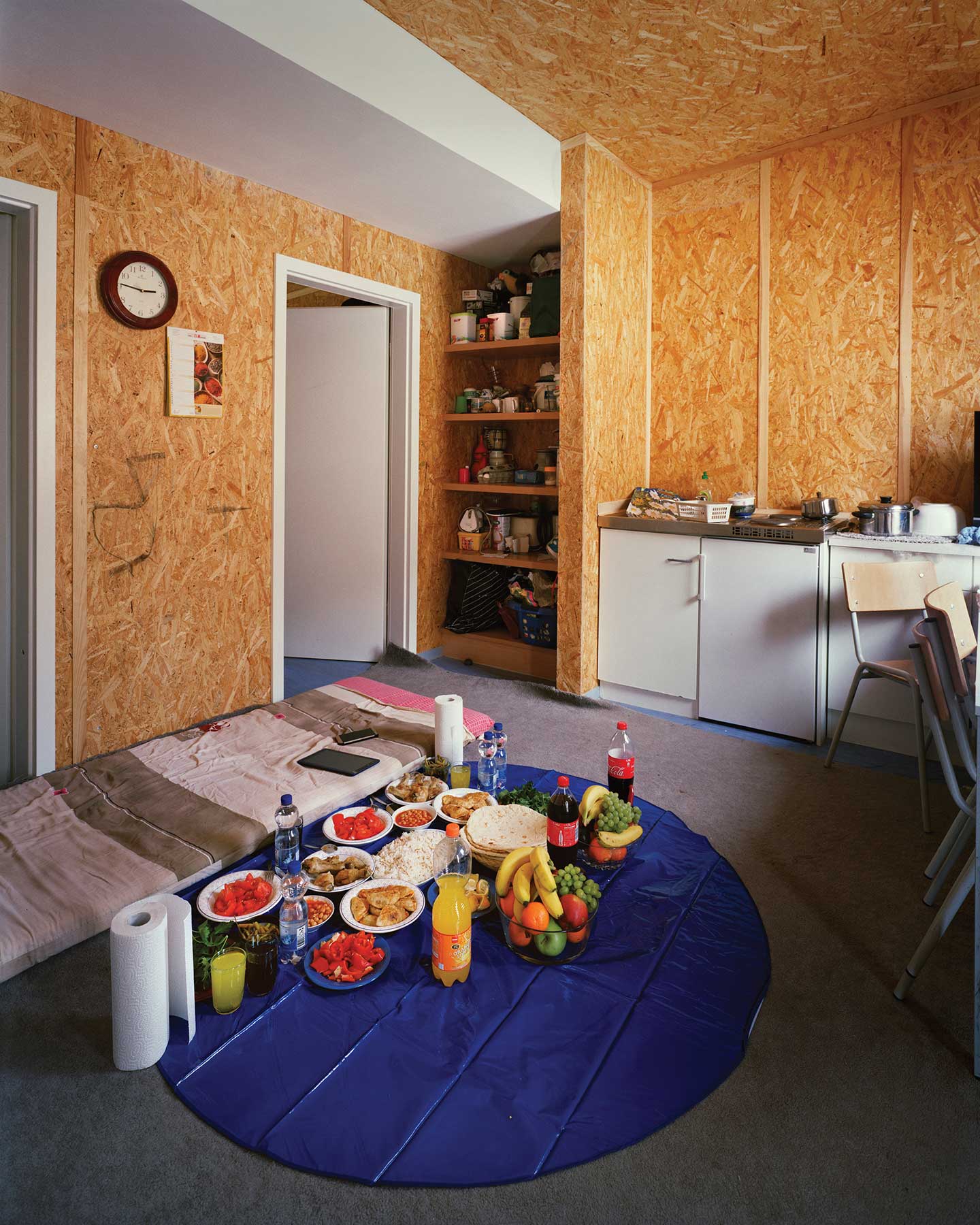

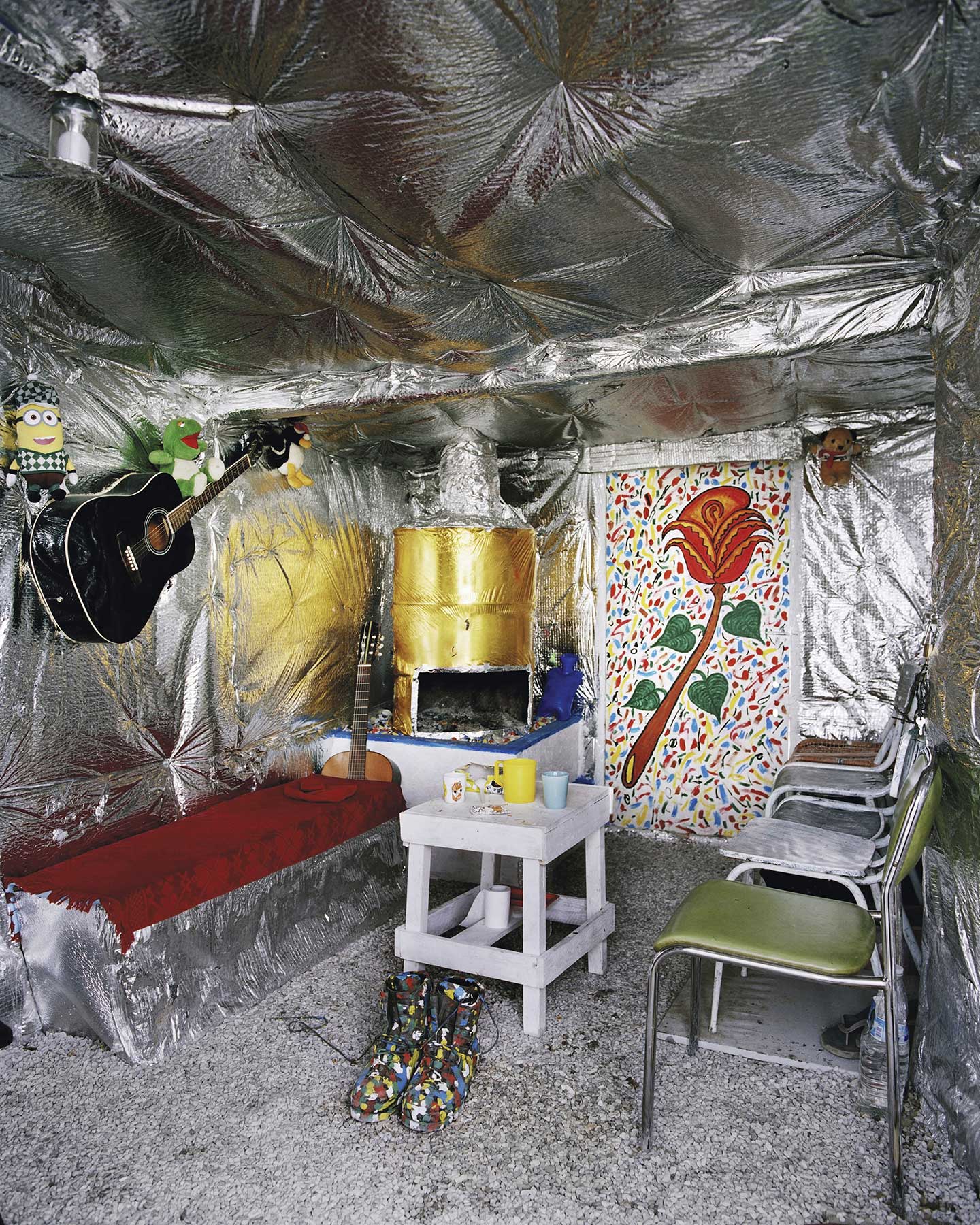

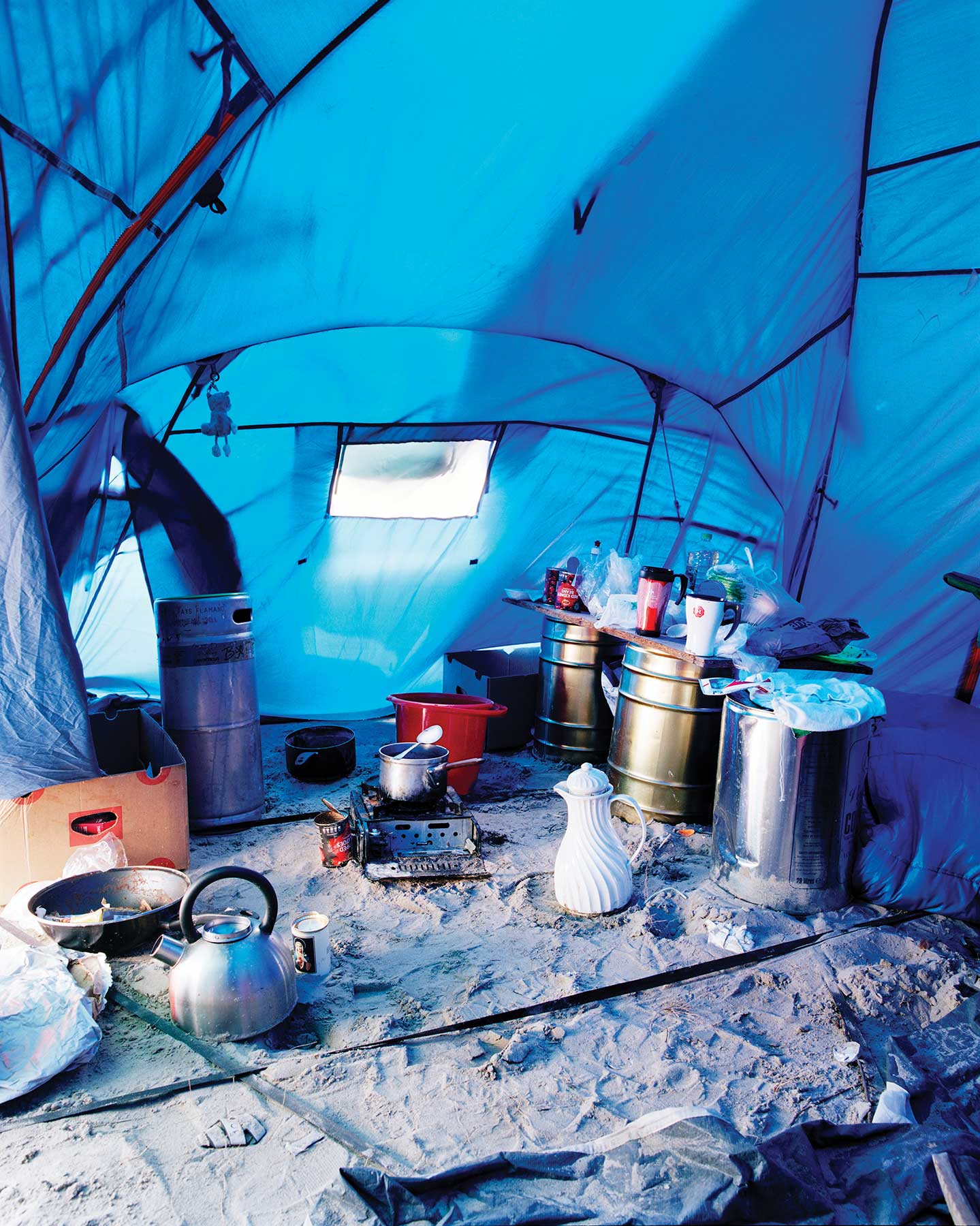

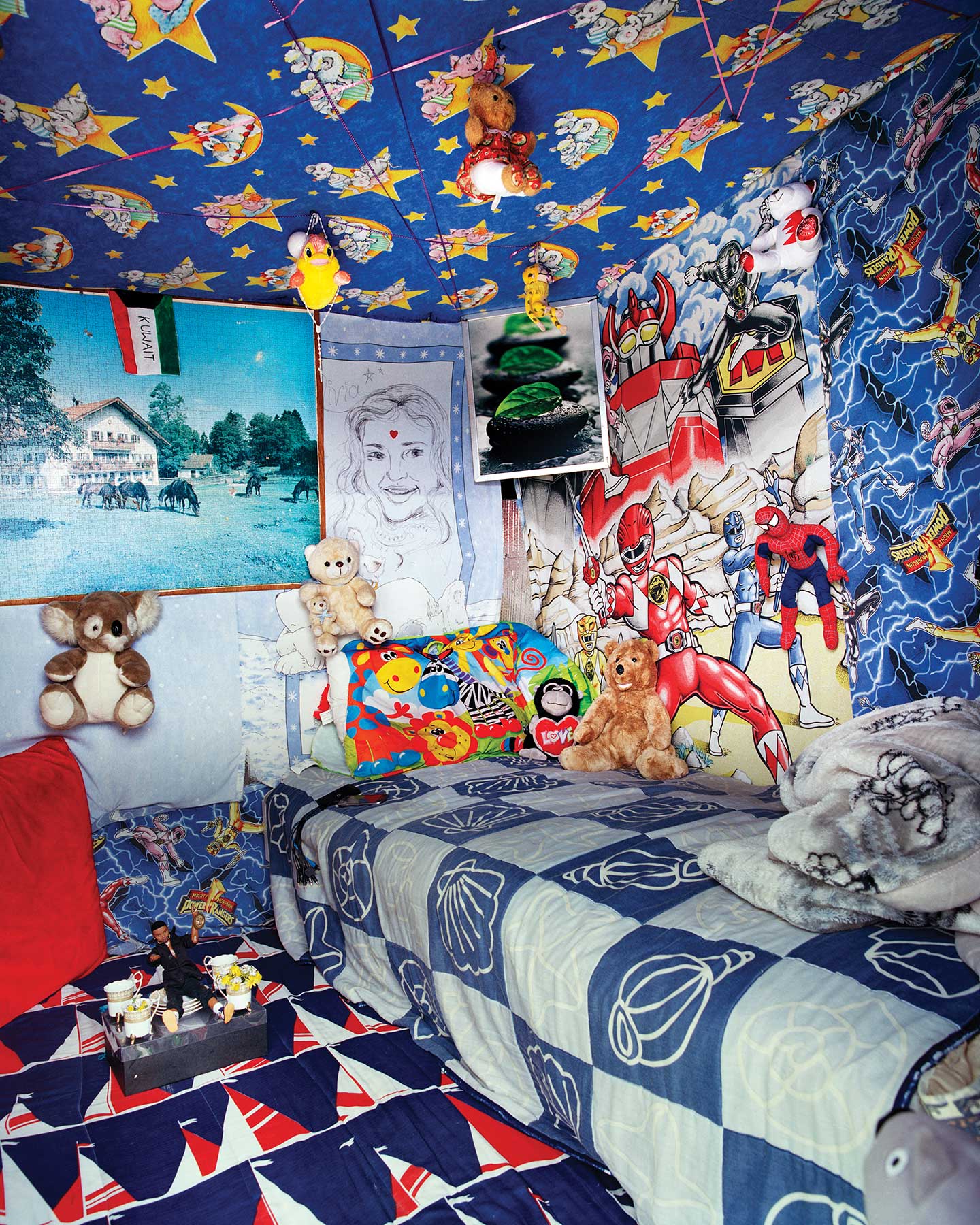

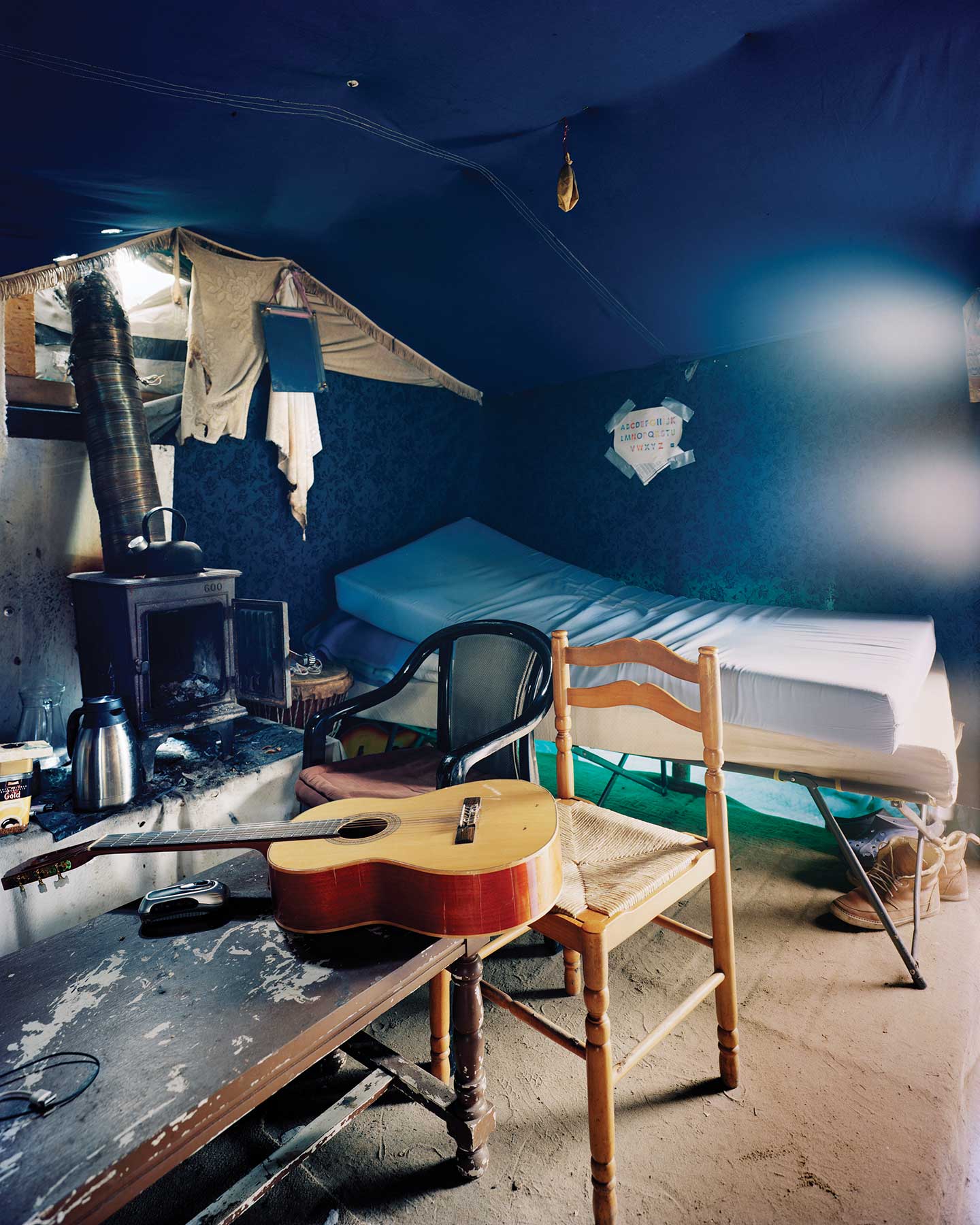

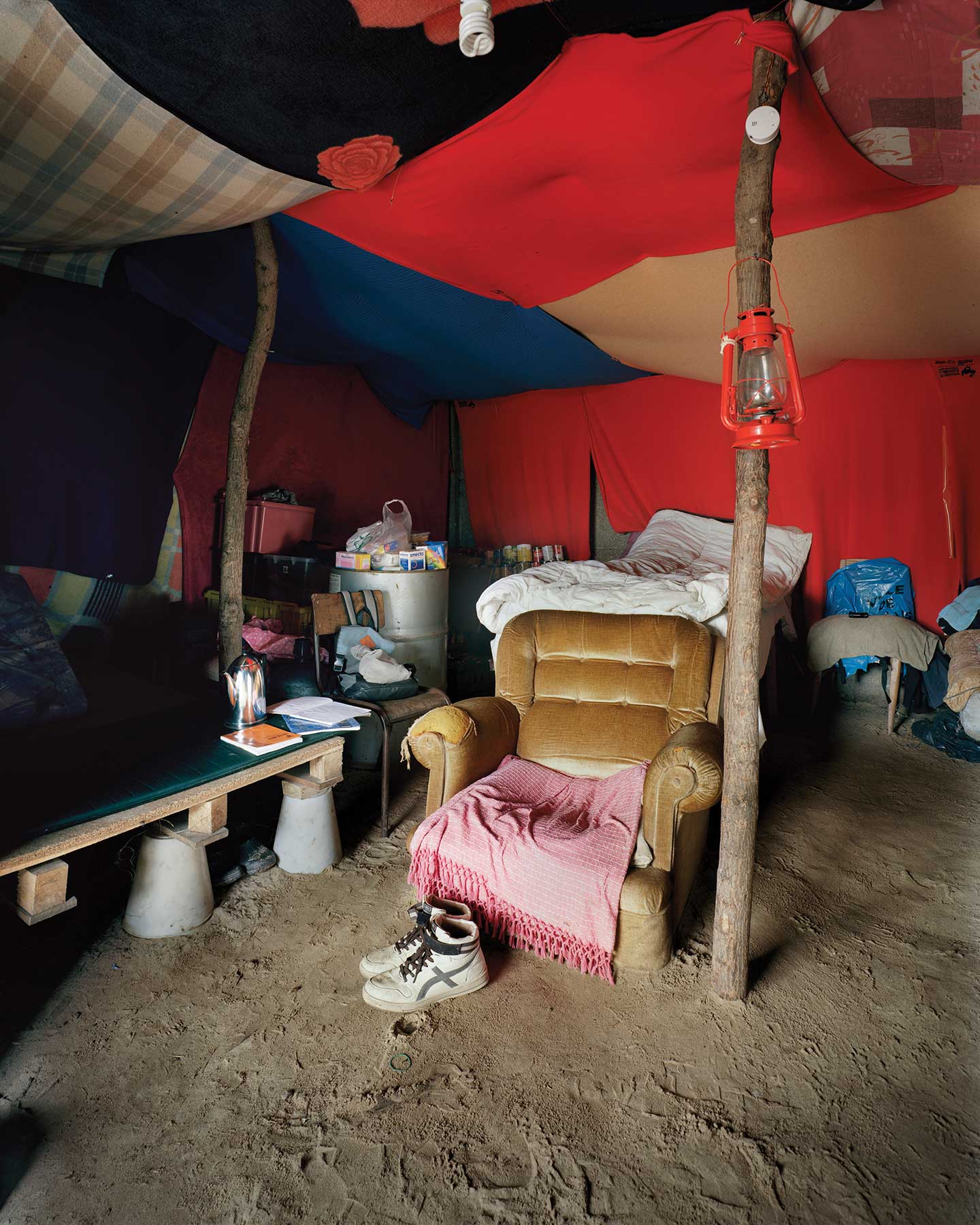

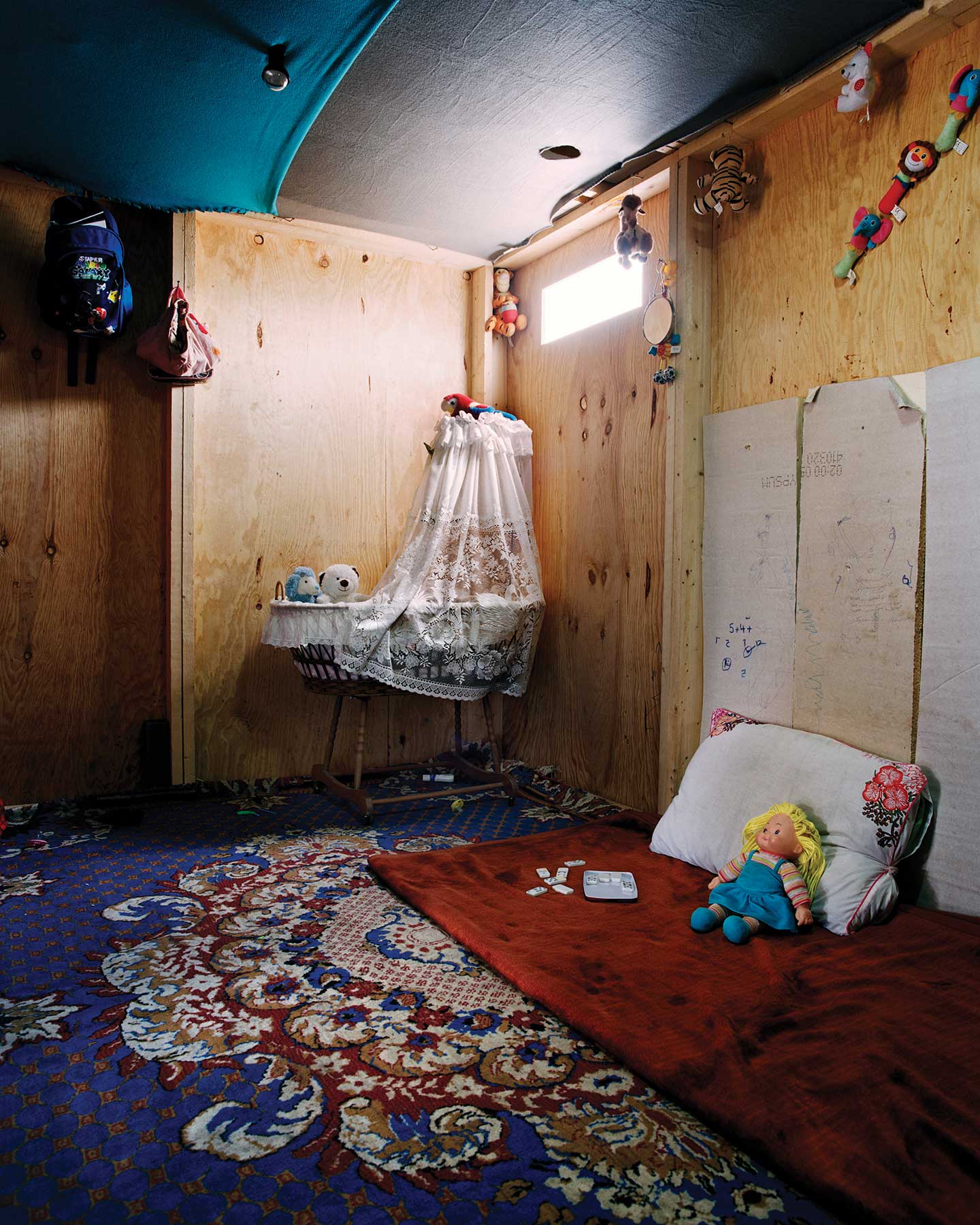

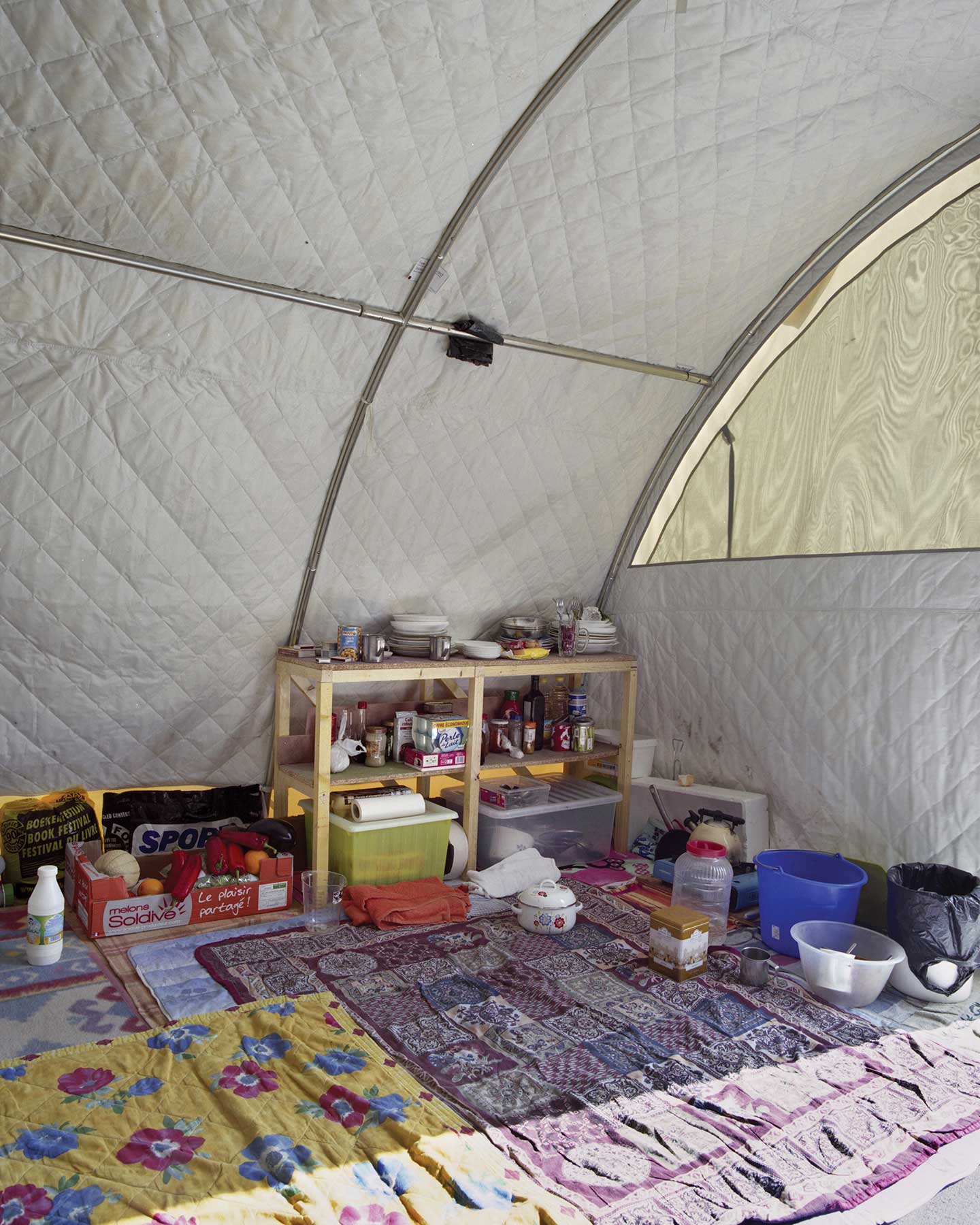

This series showcases a more intimate kind of human absence. The spaces left behind invite less archaeological reverence than musings on the material culture of modern displacement: here are the standard materials – polyethylene (tarps), polyester (tents), other miscellaneous plastics; plywood and crate wood and scavenged wood; hessian bags branded with the names of international relief agencies; the usual discarded and donated furniture, matting, bedding, clothing, etc. – that constitute basically any refugee camp anywhere in the world in the last half-century. The aesthetic feels timeless because, more than anything, these camps fulfil a function, and that function is timeless.

But Fert doesn’t stop there. He’s drawn to spaces that vex and tease that function, or mask it, spaces that feature some straight-out head-turners (what we might regard as ‘found furnishings’): a proudly upholstered club chair on tamped sand; a lace-curtained rocking bassinet; shack walls covered in Bradford City AFC-branded cladding. And are those really two stuffed tigers? Is that Kermit the Frog riding a black guitar? Ten-up combat boots painted in the style of Fahrelnissa Zeid?

Nothing if not personal. Looking at these rooms, we’re forced to scale back from the abstract and statistical to the human, and not just the human but the specific humans who have imposed their personalities on these specific spaces. Who have made choices even while making do. (This soft toy put right here; this fabric with that pattern put there, to that purpose.) Who have made an assertion of control even in the knowledge that here, all such assertions are provisional, are subject – just as they are – to the sufferance of the state.

Most of the rooms in these photos have since been bulldozed or burned down. Most of the fixtures and objects in these rooms have been separated from their owners. For me, this charges these objects, and these rooms, with almost unbearable pathos. Imagine having nothing, having already forfeited all your possessions (people smugglers profit by transporting bodies, not baggage), to come by things, and cherish them and make them yours, only to give them up again and again when you move, or are moved, on. Then to prepare, even pose, the next space with pride (the beds are made, the floors swept, tea and fruit proffered), so as to step behind a prize-winning French photographer, watching as he centres in his frame, for the brief blink of a shutter, your marginal existence.

So I’m glad the people are out of shot. People come with demands. Bodies with their gravity, faces with expressions, asking to be looked at, looked away from, looked past. The faces connected to these spaces (shown in Fert’s full series, Refuges) are all black and brown, belonging mostly to men, often in hoodies and beanies. Faces, in other words, we’ve been conditioned to fear. To distrust and despise. (Think how heavily charities lean on images of women and children.) No matter how well intentioned, your first thought looking at the faces of these men would not be ‘survivor’ or ‘victim’, and yet these are pretty much the only things – by virtue of their very presence in Katsikas, or Grande-Synthe, or the ‘Jungle’ in Calais, or the ‘Calais of Italy’ in Ventimiglia – we can be sure they are. You’d look at their faces and you’d think what you’d think and then, depending on what you are, you’d move to confirm or compensate for your bias. Either way, you’d be dealing in conjecture. You’d be drawing tendentious links between human and habitat, you’d be adjudicating narratives: Where did you come from? Why? Are you who you say you are? What have you done? What will you do?

Your gaze, that is to say, would be political.

You can’t remove the politics by removing the people. But maybe you can steer your gaze towards a deeper political point. Here’s the point I took from these photos: Fert’s interiors don’t – can’t – tell us whether their absent occupants are from Sudan or Syria, Iraq or Pakistan or Afghanistan. They don’t tell us their occupants’ ethnicities, nor which variant of which Abrahamic religion, if any, they follow, nor which side of which war or feud they fall on, nor how culpable or innocent their participation may have been. They don’t tell us whether the occupants are ‘genuine’ refugees or ‘merely’ economic migrants.

What they tell us is that these people are (still) people, with their own idiosyncratic interests and tastes. With their strange, specific dignities. With identities (still) unsubsumed by political labels. By focusing on the particular, Fert frames the negative space for a more general point: there will always be conflict; there will always be displacement. These are realities as impersonal as any natural law. To a refugee in a camp, the mechanisms of post-Westphalian states are no less impersonal. States will do what states do, which is protect and preserve themselves, which means (excepting cases of economic advantage) keeping you out. As the news confirms over and over again, the two consistent poles of state policy towards refugees are deterrence and deportation: what happens in between is nobody’s business, is ‘processing’. (As I write this, the US administration is arguing in court that it has no obligation to provide soap, or a place to sleep, to detained migrant children.) If you’re a refugee in a camp, you’re out even when you’re in; your human particularities don’t matter because the camp exists to fulfil the state’s function, not your human need.

Outside, inside. These rooms, especially those in the infamous ‘Jungle’ of Calais, throb with the mania to keep the outside outside. Outside is rubble and mud, ruts, sumps, sand and ash. Burning garbage. Squalor and sewage. Rats the size of rabbits. Hostile traffickers, hostile locals. Outside is fifteen-foot cyclone fencing and tear gas and policemen in riot gear (and even worse, policemen in mufti). Outside you’re exactly what they say you are: another ingrate, fouling your own home, but then what else did you expect from these people?

There’s one photo I haven’t touched on. The last photo in the series shows an apartment room in the 18th arrondissement of Paris. It is flooded with natural light, its wooden floorboards level and beautifully stained. What look like Haussmann windows are recessed and curtained. There is an inset shelf with casing, filled with books and toys, and a board-and-batten chair rail, above which hang ornaments, framed prints. The room is full of such grace notes. It’s a well-built room: one that rain wouldn’t breach. One, more importantly, that the state could not breach, not without legitimate cause. It occurs to me that home is an embodiment of freedom, and one universally understood and respected. For all the moment’s talk of assimilation, I’ve yet to hear even the most rabid nationalist wanting to dictate how immigrants should adorn their own homes. Inside is all yours, is sacred.

My gaze keeps returning to the top of the photo, to the ceiling cornices with their floral mouldings and fluted dentils. All that intricacy. As if to say: This is about more than function. As if to say: This room will last. You are safe here. You can make plans here. The decorative, in this photo, coming at the end of this series, has never felt so necessary. But that’s not right either. The cornices are not merely decorative. Their beauty is part of their function: they disguise and distract from the sites of joinder – the places where different planes meet, the places where all you’d otherwise notice would be warp, leak, lines out of true.

All photographs © Bruno Fert