Spring in Canada can be an unconvincing season. In Montreal, where I used to live, the weather will suddenly turn warm, and the sun can seem like a youthful idiot shouting THERE’S HOPE, THERE’S HOPE to an audience of corpses. On a day like that, I drove to a place that changed my life.

I was approaching forty. I was madly in love. I was daily aware of the inadequacy of words to describe the joy and ache I felt, and at the same time I had no need for words. I went to a lousy therapist and told her how good I felt and she said she had heard the same from a number of men recently: adultery had done them good. I was in the middle of a divorce, and had done some truly shitty things to people I loved. My son was born in the midst of my failure to stay married. Regret had left bruises behind my eyes.

On that spring day when the sky was hot and the ground was dead, I found myself face-to-face with a chimpanzee named Spock. I had been reading about chimps for a couple of years. I was intrigued by the fact that we classify ourselves as great apes, and have more in common with chimpanzees, genetically, than chimpanzees have with gorillas, and yet rarely talk about ourselves, seriously, as apes.

I had begun writing a novel about chimps based on my book research, and found that I needed to meet some in the flesh. I wanted to know their movements, their sounds, their anger and their smell. I discovered a sanctuary that was less than a half-hour’s drive from my apartment in Montreal. It was home to nineteen chimpanzees and various other animals rescued or retired from service to humans.

Spock was a little over thirty years old and weighed more than two hundred pounds. He approached with his hair on end, loping along a steel-enclosed catwalk. The co-founder of the sanctuary, Gloria, stopped near him and said, ‘There’s my Spock!’ in a childish tone. At first it seemed as appropriate as saying ‘Hey, little fella’ to Genghis Khan. Spock had shoulders like boulders and homicidal eyes. He was the first adult chimp I had encountered so closely and I hadn’t expected to feel such fear. His hands were massive and he seemed to embody most of the impulses that we legislate against. Without that steel fence I would have been his plaything. But when he heard Gloria’s endearing voice he bobbed his head, softened and showed the face of a grandpa.

When I first started reading about chimpanzees I was attracted to the story of ape language studies: the fact that other apes could learn symbolic languages and communicate with us was moving to me. There was a chimp named Lana who lived in a room at Yerkes, a primate research centre in Atlanta, communicating with humans through a system of lexigrams called Yerkish.

She spent her infancy in that small room and for long stretches of time her only companion was the computer. She received physical contact with researchers when she demonstrated her comprehension of symbols or was able to create a grammatically correct sentence.

Her main interlocutor was Dr Timothy Gill, whom she knew as Tim. A typical sentence of hers would be please machine give coke, where the machine was the computer that dispensed various treats and also played movies and music. When Dr Gill was involved in observation, Lana would often want him in the room with her. please tim tickle lana.

Like most human children, Lana had an early understanding of the concept of no. She could be chastened by it, when she saw it on the machine, but she could also use it to assert her own needs and disapproval. When one of the researchers drank Coke on the other side of the observation window and there was none available to Lana, she stamped her foot and hit the no button. When Tim put a slice of banana in his mouth instead of in the dispenser for Lana, she hooted angrily, ran to the keyboard and said no, no, no.

Lana knew the lexigrams for bowl and can, and was learning the distinction between containers. Tim arrived one morning with a bowl, a can and a cardboard box. While Lana watched, he put an M&M candy in the box. Here is Lana learning the meaning of box.

Lana: ? tim give lana this can.

Tim: yes. (Tim gives her the empty can, which she at once discards.)

Lana: ? tim give lana this can.

Tim: no can.

Lana: ? tim give lana this bowl.

Tim: yes. (Tim gives her the empty bowl.)

Lana: ? shelley (sentence unfinished)

Tim: no shelley. (Shelley, another technician who worked with Lana, is not present.)

Lana: ? tim give lana this bowl. (Before Tim can answer, Lana goes on.)

Lana: ? tim give lana name-of this.

Tim: box name-of this.

Lana: yes. (Short pause, and then) ? tim give lana this box.

Tim: yes. (Tim gives it to her, she rips it open and eats the M&M.)

What I like about these transcripts is the childishness, the simplicity and familiar energy of a little girl wanting company and treats. I was charmed by chimpanzees and bonobos because they seemed so human. Over the years I have pondered the narcissism of that.

The one who charmed me the most in books was Washoe, the famous chimp who learned American Sign Language in the late 1960s. Roger Fouts wrote a wonderful memoir called Next of Kin about his relationship with Washoe – he was her teacher, student and friend. Here he is recounting one of their conversations in American Sign Language, where he uses upper-case letters to transcribe their signs:

She once pestered me to let her try a cigarette I was smoking: give me smoke, washoe smoke, hurry give smoke. Finally I signed ask politely. She responded please give me that hot smoke.

I love that she throws that word in: hot. From a writer’s perspective, adjectives are agents of persuasion, of surprise, of forcing a reader to look. Washoe uses her hands to give that smoke an urgent presence.

I found myself playing catch one day with a chimpanzee named Binky. We were throwing an apple back and forth – he was standing behind a fence inside his metal-and-concrete bedroom. Binky was in his late teens and was big. He scared the hair off me. The game went on until Binky dropped the fruit. As I bent down to pick it up Binky took a mouthful of water and drenched my face when I stood. He was agitated and gestured towards a bottle of Gatorade that was on the table behind me. As I absorbed the humiliation of having water spat in my face, I realized that what he had wanted all along was the bottle of Gatorade. The apple was his tool for making friends and getting my attention; it was like Washoe’s talking hands. Once I gave him the Gatorade he threw the empty water bottle at my head.

I came to believe that what chimps do with hands and fingers, people do with their tongues. In human life words woo or sway, they provoke, inform and speak of an individual’s perception. Our words help us find our place in a group, the words of others tell us whether they are one of us. If speaking and tool use come from the same place in the brain, then I thought of a word as a tool. A word is touch. It became a way for me to understand the physical origins of language, its physical effects. Instead of focusing on language as something that distinguished me as a human, I started thinking about words as fists and caresses, fingers grooming and soothing.

The sanctuary near Montreal was a thoughtfully designed place – all areas were built with chimps (and safety) as the main consideration. Each chimp had his or her own bedroom, with an elevated platform and places to nest as they might in the wild. There were indoor and outdoor play areas, and while the outdoor ones were lovely and spacious, the indoor areas were also large and varied; this was after all a suburb of Montreal and even rugged-up humans could not be comfortable outside for long. The indoor space had concrete floors, lounge areas and climbing apparatus. Some spaces had been divided into identical-looking parts because not all of the group got along with one another. There was a big kitchen at the centre of all the bedrooms, where a TV was often on, and where the days played out with the endless preparation of meals. The chimps had trolleys laden with food in front of each of their bedrooms, which they could reach through gaps in the latticed steel that sealed both chimp and human worlds.

I had read about the recognition and revulsion that people commonly feel when they first meet chimpanzees. Their company can force us to dispense with our fictions, and those who believe their own fictions too deeply are often disgusted by what looks like a parody of our behaviour, of our bodies. It was the time of the month for one of the females, Pepper. Her menstrual blood dripped like Kool-Aid from the folds of her swollen pudendum, and to call it a pudendum, with the word’s implication of shyness, is to do that thing a disservice. It was as large, pink, arrogant and jowly as Winston Churchill’s head.

What I immediately learned was that to have a generalized perception of the appearance of chimpanzees is a mistake. They are truly individuals, and understanding that so vividly was a step for me towards respecting them more deeply. Famous chimps like Lana are young, pale-faced and endearing. The common cultural perception of them is as little goofs, man-children. While touring my novel I have often been asked for photos of myself with one of them. Producers wonder if I might bring a chimp with me to radio interviews. I had known that chimps grew large, that their faces darkened, that they were violent and seven times stronger than human males, but to see these facts in the flesh was truly intimidating. They wouldn’t sit quietly in a studio.

It wasn’t just their size – not all were large. They had a presence that demanded all of my attention. I felt like I had entered a room of pickpockets who were honest about being pickpockets. These are our switchblades. I was always on the other side of a steel grid, but I rarely felt safe. Imagine walking into a bar in a small town where everyone is unfamiliar to you. Some are sizing you up, pondering your manner and the enemies you remind them of. Some are curious to meet you. You have no common language except the movement of your bodies. How do I present myself to creatures that don’t know my language, that won’t appreciate my irony and subterfuge? What am I when my words are not understood?

I talked to all of them in baby talk, and everyone who worked there did the same.

The individuals who were curious came close to the metal grid. They put their worn black fingers through the holes to reach out. I was warned not to touch them because the mischievous among them might hold onto my hand and not let go. They might break my fingers or bite them off – as had happened to others. It was nonetheless very hard not to reach out in return. Some gestured with the familiar inward wave of the hand, come here. They held their hands palm upward under the fence, tried to reach through it.

Several of them were HIV-positive. Fifteen of the original nineteen had come to the sanctuary from a biomedical lab in upstate New York called LEMSIP, the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates, affiliated with New York University. The chimpanzees had been deliberately infected with various strains of HIV, hepatitis and other diseases. Chimps and humans can pass each other everything from polio and herpes to the common cold and flu. I signed a waiver stating I would make no claims against the sanctuary if I happened to be infected with something.

I was so keen to connect with them that it didn’t give me pause. They spat in my face several times. Chimps in captivity will often spit, either to get your attention or to tell you to fuck off. I suppose their illnesses sharpened these already edgy exchanges for me.

Everything was heightened – fear, curiosity, the search for trust. Because many of them embodied such a coiled menace, the usual dynamic of joining a group – the awareness of judgement, the tension between welcome and rejection – felt exaggerated. I have rarely been so rationally aware of my insecurities. I had an unnerving sense that I was being watched, even by that one over there with her back turned. A male would suddenly arise with hair on end, stamp his foot and hoot, the group would be disturbed, the noise would be deafening and the air thereafter all the more electric. Even in moments of peace there was unease.

Pepper came towards me and we sat across from each other. I looked into her eyes and thought of the importance of eye contact in human life – strangers on a subway, how we know when someone is listening. I looked at her calmly and thought she was lovely. Her fingers were elegant. There was a light in her eyes. Her hand was outstretched to me under the fence and I wanted to hold it.

What I know about humans and human history is that we are empathetic, altruistic, imaginative and creative; we are social and our societies and families always contain some sort of hierarchy; we are miserable, depressive, murderous and greedy; we are afraid of strangers but sometimes make them welcome; we need and fear touch; there is politics to our food, politics to our mating, and meat is controversial; we make tools, and rely on others to pass on solutions; we share, beg, feel jealous, masturbate, care for others’ children, kill and kidnap others’ children, and we are judged for how we suffer and nurture our young.

All of this is documented chimpanzee behaviour. I came to the sanctuary already knowing, intellectually, that we were kin, but meeting Pepper made me feel it more deeply.

She was HIV-positive and had endured decades of biopsies and gunshot anaesthetics. As I heard some of the details of her life from Gloria, Pepper was sizing me up and urgently inviting me to touch her. She tried to groom a small freckle off my hand. I understood her grooming noises and gestures as a desire to get to know me, to help me.

When someone suffers torture and imprisonment, and comes out the other side to make friends with strangers, is this the apex of humanity, a triumph of will, or is it ape nature?

In my visits to this and other sanctuaries there were plenty of moments of strangeness and discomfort, times when I knew profoundly that I was not a chimpanzee. They are so loud, for one thing. Especially in rooms with concrete floors. I have an audio recording of myself presenting a bottle of Gatorade to an adult chimp named Regius. His pant-hoot starts like the breath of a scurrying dog and then rises and thickens, gathers a mood of fear and revelation and ends at a pitch of such violent joy that whenever I replay it I laugh and feel uncomfortable. At the time I remember thinking, Christ, Regius, it’s only Gatorade.

Of course, that excessive joy and lack of shame are what can make them so attractive. There are many stories from the primatologists Frans de Waal and Jane Goodall about chimps practising deceit, creating a fictional disturbance to occupy a group in one place in order to get their hands on food somewhere else. I would never claim that they are what we would call innocent or honest. But their behaviour reminded me of how much we learn to dissemble in our own groups, and how refreshing it can be to encounter directness. Regius took a liking to my partner on one occasion; he lay on his back, spreadeagled, and invited her to touch his balls in a way that made me blush. I saw a middle-aged female named Sue Ellen savour a bowl of spaghetti with such Mardi Gras abandon that I cried and made it an important moment in my novel.

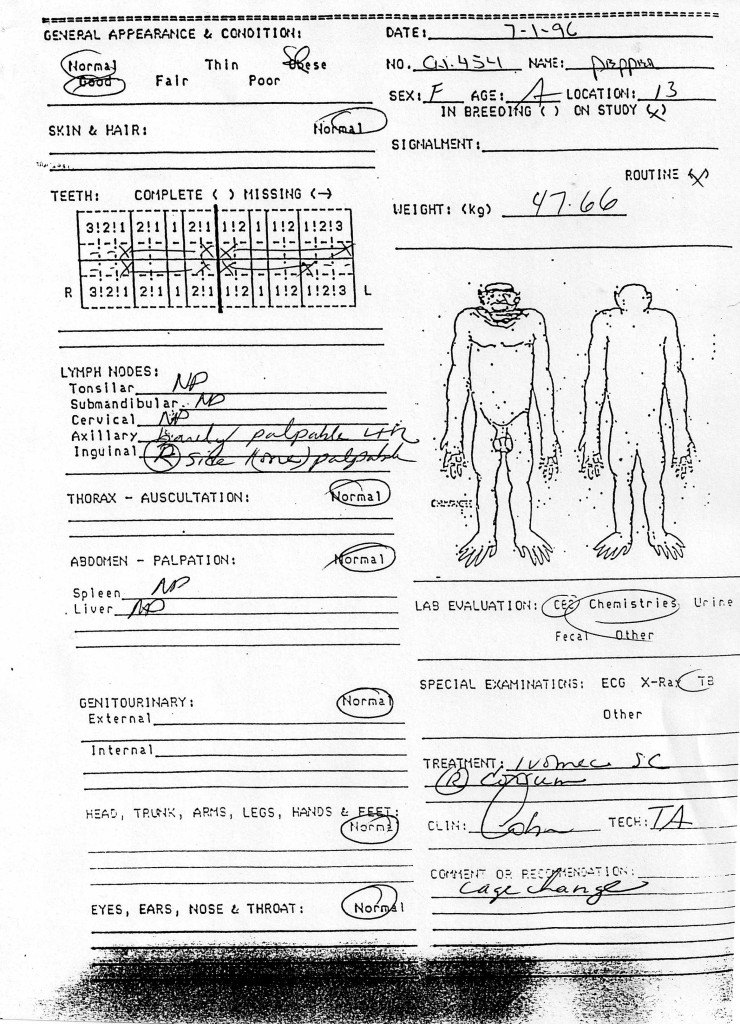

Perhaps knowing their histories made a difference. Months after my first visit I went through Pepper’s medical file from LEMSIP. Her blood work was sometimes processed by independent labs where the technicians did not know that she was a chimpanzee. Her cholesterol tests were set out identically to mine – the same range of normal. When her blood tested positive for HIV, the form from the lab declared that it was legally required for ‘all test results [to] be relayed to the patient only by physicians or personnel suitably trained to counsel the individual as to the significance of the report’. Words from a caring physician that might soothe the human patient, words that might amount to a hand on the shoulder or a hug in the wake of bad news; words completely without meaning to a chimpanzee.

I read a number of scientific papers that emerged from this HIV research. The language was fascinating. Here is a sing-song description of a vaccine being prepared: ‘The gp160-MN gene was placed under the transcriptional control of the H6 vaccinia virus promoter and then recombined into a canarypox virus. The resulting ALVAC-HIV vCP125 recombinant was amplified in specific-pathogen-free primary chicken embryo fibroblasts, lyophilized, and stored at 4 degrees Celsius until used.’

I puzzled through these papers and found clues of Pepper and her future friends at the sanctuary being the subjects of these experiments (the chimps were identified by numbers tattooed on their chests), and as I tried to understand the language I realized that these barely English descriptions were the sounds of a species trying to survive. When I learned more about these environments and trials, what a macabre and bloody harvest they amounted to, I saw these technical terms, these arcane clinicisms, as a means of doing dirty work and not having to look at it. The research was predicated by one sympathetic animal acknowledging the genetic and immunological kinship of another; yet it could only be conducted by ignoring most of that kinship. The diction makes it difficult to remember that there were living bodies involved.

The quote above was part of a study that took place over five years. What this meant for Pepper and the others was thousands of days and nights in a cage, hundreds of knock-downs, infections and a solitary, relentless battle with disease. Pepper was in those cages for almost thirty years.

Having read so much about chimpanzees I had to adjust to them as animals when I met them, as flesh and blood rather than abstractions. Study after study presents them as embodiments of data: they are sensitive communicators; they remember sequences of numbers; they get depressed in middle age. The data are often wonderful and telling, but they somehow collect in a corner – that place we look when we are searching for random facts and cute coincidences, those moments when the ‘natural’ world might amusingly reflect our own. The further we get from having to find our own food, the less awareness we have of our nature. Understanding these individuals at the sanctuary as animals meant adjusting to myself as an animal. I was not finding an ape within. I was realizing that the whole of me is an ape, that our genes, our biology, our behaviour in groups are not just coincidentally related to other apes but inescapable facts that I arise and go to sleep to. That I dream with.

We all embody a range of contradictions. Chimpanzees and humans hate to see injuries, and cause them all the time. Chimps and humans choose their factions, betray their friends and use enemies to consolidate friendships. While I hate the violence that humans have inflicted on chimps, I’ve seen chilling and deplorable fights between chimps themselves – capricious acts of bullying and murder which show that they can have as much disdain for life and kin as we can.

I have had this ambition to find a language for the ape reality of days. Alpha chimps, according to Frans de Waal, can engender such respect that other chimps will bow to their sleeping bodies. That image has stayed with me, and made me think that an alpha, in ape societies, is one who controls conscience. When a male chimpanzee wishes to eat someone else’s fruit or have a dalliance with an attractive female, he will go to a sleeping alpha and bow. A contrite sinner kneeling before a priest. Clearly the alpha is present in his mind as he negotiates his desires. To me, this is why various godheads have so successfully brought people together through human history – it is natural for apes to look for an arbitrator to govern individual desires, and natural for us to think of others who may or may not be present as we step forth and make our mistakes.

The alpha is part of a dynamic of dominance and submission that plays out constantly in our lives. When my three-year-old daughter wants something, she will sometimes ask me first. I can see fibs and deceit beginning to bloom in her pupils like tiny black dahlias, and I lie to her regularly to get what I want. If she makes a mess or hurts herself she will come to me for comfort or to apologize if her mother isn’t around, and if we are all together she treats me like dirt. She is my alpha as much as I am hers. I find it helpful to think of an alpha as a real or imagined force greater than myself that I may or may not bow to as I go through my days: a voice or force to be considered. My father, partner, editors, ex-wife and bankers have all been my alphas – people I have needed to please whose voices have occasionally checked my actions, and my desires. This is basic ape behaviour, human behaviour.

I no longer see human beings as I used to. I get frustrated that we have a limited language for the very nature that gives us language, no way of calling ourselves ‘apes’ without inducing giggles or indignation. Part of the ape reality of my days is that I often forget I am one. Trying to remember it has sometimes left me lonely.

I like watching hockey. When I see crowds cheering and hooting, egging on fights and deploring them when someone is seriously injured, I think: apes. I look at my competitive side, my need for friends, my wish to be heard, and I think: ape. Ethnic conflicts and superpowers rattling sabres: apes. Debates over immigration. Mothers supporting other women and biting the backs of rivals. I think of magazines and newspapers as grooming sessions, gatherings of the like-minded who use words and idioms like handclasps, each contributor wanting to steer the group towards his or her perspective. It might sound reductive to some people, but it has been a comforting way of understanding my life.

I left my wife shortly after she gave birth. The trauma of that changed me, and my family, forever. I know that when I watched my son’s birth, my mind in a despicable mess, he came out gold and wet and I had two clear thoughts: I am proud of him already; and, how can we have witnessed the spectacle of birth so many billions of times and yet believe we are separate from animals?

Lana, the joyful, curious chimpanzee who learned how to use the computer to talk to Tim, ended up being kept in the lab at Yerkes and became part of the breeding programme. I recently met a woman who worked with her on that original language study. She had returned to Yerkes and met Lana again, forty years later. She said that Lana clearly remembered her. Lana had had several kids at Yerkes, all of them taken away from her for various studies. The woman said that Lana’s eyes were distant, and sad.

I cherish my partner’s eyes, and she accepts the fact that I think of her as an ape. Our daughter draws us to the playground. She plays in the sandbox and tries to take toys from other kids, cries when they are taken from her. The adults arbitrate, teach the kids how to share. When the kids are upset we all say ‘use your words’. Over there some women are talking about something serious; they are making it clear that they are friends and that I am not welcome to join their conversation. The men near the swings stand with folded arms and talk about their work, occasionally making eye contact with each other. One of them says he has learned to hustle more since he became a father, doesn’t worry about rejection so much and doesn’t get angry when people don’t like what he’s selling. He’s getting along better with everyone and his bank account shows it. His kids are tumbling, fighting and playing. My daughter is particularly good at the monkey bars. I’m hungry, and irritable because of it, and I will probably wake up in the night in some kind of panic, or my partner will, my daughter definitely will; all of us scared of the things we can’t see. People at the playground say goodnight, we all go home to eat, to read stories and watch TV, forget ourselves on the couch.

Image courtesy of Colin McAdam